By Andrew Norris

Introduction

The new U.S. tri-service maritime strategy, Advantage at Sea, which refers to the three maritime services (Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard) collectively as the single Naval Service, largely focuses on great power competition at sea against peer or near-peer competitors.1 However, although the Naval Service has to be configured and trained to prevail in high-intensity armed conflict, unless and until such conflict occurs, this competition at sea will play itself out through interactions short of war across what the strategy refers to as the “competition continuum.” By increasingly and successfully engaging in activities short of war against maritime competitors and other malign actors, the Naval Service will accomplish a central pillar of Advantage at Sea, which is to “prevail in day-to-day competition.”

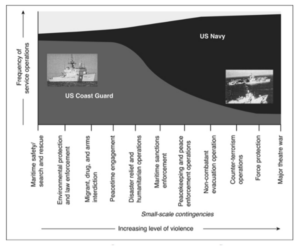

In addition to being built, equipped, manned, and trained to compete in operations short of war, the Naval Service also has to be able to plan for campaigns and major operations in this space to ensure the most effective and efficient employment of scarce resources—not only to achieve the United States’ strategic goals, but also to assist allies and partners in achieving their own goals and objectives. This ability to plan at the operational level will increasingly include operations at the lower, “constabulary” end of the competition continuum (see Figure 1), an area of far less familiarity to the U.S. Navy than to the U.S. Coast Guard. Operations at this level, which promote a rules-based international order at sea, are “increasingly being seen as a crucial enabler for global peace and security, and therefore something that should command the attention of naval planners everywhere.”2

This article asserts that the U.S. Navy will increasingly be called upon to operate in the constabulary end of activities short of war and proposes a 4-part constraints, restraints, enablers, and imperatives (C-R-E-I) analytical model for preparing the staff estimate to inform the mission analysis phase of the Navy Planning Process (NPP),3 when utilized to plan for such activities. In doing so, it builds upon the scholarship of Professors Milan Vego and Ivan Luke of the U.S. Naval War College.

Professor Vego, in his recent article “Operations Short of War and Operational Art,” discusses the precepts of operational art (which are embedded into the NPP) as they apply to operations short of war.4 While a masterful Vego product as always, the article’s focus on operations at the higher end of the spectrum of violence involving the kinetic application of military force to achieve higher end political objectives—such as Operation Allied Force in Kosovo (1999), Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan (2001-2002), and Operation Odyssey Dawn in Libya (2011)—leaves unaddressed the question of how operational art, as embedded in the NPP, needs to be adapted to account for the unique aspects of maritime operations with a constabulary derivation. This article attempts to fill that void.

The other theoretical inspiration for this article is Professor Luke’s approach to understanding operations short of combat at sea, as set out in his article “Naval Operations in Peacetime: Not Just ‘Warfare Lite’.”5 His underlying thesis is that:

[t]he things the U.S. Navy and other navies of the world are doing in peacetime today are fundamentally distinct from naval warfare, and they are important enough to demand an expanded naval theory that incorporates their unique aspects. Continued reliance on naval warfare theory alone puts the [U.S.] Navy at risk of not doing its best to meet the challenges of, or not capitalizing on the opportunities present in, the maritime domain today.

In recognition of the “broad and growing array of legal regimes, treaties, and sources of authority that need to be fully appreciated, understood, and leveraged” to achieve success in operations short of armed conflict, Professor Luke proposes a theory of legitimacy as being more appropriate than the theory of naval warfare to such operations.6 This article endorses the centrality of legitimacy, grounded on underlying authority, as a unifying theoretical construct of the authority mechanism for success of operations short of armed conflict, and “operationalizes” it by providing a mechanism—constraints, restraints, enablers, and imperatives—for thoroughly accounting for the factors that collectively constitute the authority and legitimacy of an intended operation.

Before arriving at the proposed analytical model, this article will first discuss operations short of war on the competition continuum and distinguish between those with an armed force derivation and those with a constabulary derivation. It will then demonstrate how the Naval Service, and most importantly, the Navy, will increasingly be called upon to perform lower threshold constabulary missions as part of the day-to-day competition in the maritime domain. It will then examine the need to perform those missions as part of a campaign or major operation, instead of haphazardly and situationally in response to malign activities at sea.

It will conclude by reviewing the Navy Planning Process overall, by identifying mission analysis (as informed by staff estimates) as the proper place to account for the “unique aspects” of operations short of war, and by demonstrating the inadequacy of existing doctrine to guide proper mission analysis for such operations. It is in the context of this discussion that the 4-part analytical tool will be presented and discussed.

Operations Short of War Defined and Discussed

1. Maritime security operations versus operations short of war

Professor Luke uses the term “operations short of armed conflict” to denote “naval operations in peacetime;” other commentators such as Professor Vego use the term “operations short of war.” As we have seen, Advantage at Sea, by defining the competition continuum to include day-to-day competition, competition in crisis, and competition in conflict, and by using terms such as “war” and “destroying enemy forces” to illustrate what competition in conflict means, implies that operations not rising to the level of conflict are operations short of “war.” The NPP and a host of official U.S. government products use the term “maritime security” synonymously with “operations short of war.”7 While Professor Till also employs the term “maritime security,” which he equates to the term “good order at sea,” to describe such operations, he acknowledges their ambiguity, and states that such terms must be used with caution.8

The bottom line is that a hodgepodge of terms are in common use to describe maritime operations short of war. While some may dispute the equivalency, for purposes of consistency, this article will use the terms “maritime security operations (MSOs)” and “operations short of war” interchangeably to refer to all operations short of “combat operations”—which is another term used in Advantage at Sea to denote operations during conflict.

2. Maritime security operations with a law enforcement versus an armed force derivation

In addition to settling on consistent terminology amongst a welter of options, this article also distinguishes between higher-threshold maritime security operations that have an armed force derivation and a political-military purpose, and lower-threshold9 maritime security operations that have a law enforcement derivation and typically a constabulary purpose. The former must be conducted by members of the armed forces of a state operating from a warship10 and are governed by the law of armed conflict. In the latter, the use of force is governed by rules for the use of force deriving from human rights law, and operations may be undertaken not only by “warships or military aircraft,” but also by “other ships or aircraft clearly marked and identifiable as being on government service and authorized to that effect.”11

The U.S. Navy will increasingly be expected to perform lower-threshold MSOs

According to Advantage at Sea, the Naval Service will partner, persist, and prevail across the competition continuum, employing Integrated All-Domain Naval Power through five lines of effort:

- Advance global maritime security and governance, which means operating with allies, partners, other U.S. agencies, and multinational groups12 to maintain a free and open maritime environment, and to uphold the norms underpinning our shared security and prosperity.

- Strengthen alliances and partnerships, with the ultimate aim of modifying bad behavior in the maritime domain.

- Confront and expose malign behavior by rivals, with the ultimate aim of holding them accountable to the same standards by which others abide.

- Expand information and decision advantage, which provides superiority in coordinating, distributing, and maneuvering our forces while simultaneously removing adversary leaders’ sense of control, inducing doubt and increased caution in crisis and conflict.

- Deploy and sustain combat-credible forces, which enables all lines of effort, deters potential adversaries from escalating into conflict, and ensures that naval and joint forces will defeat adversary forces should they choose the path of war.

As can be seen, though prevailing in the event of war is and always will be a core objective of the Naval Service, the lines of effort largely and properly focus on activities at the lower end of the competition continuum as the best means for prevailing in day-to-day competition. Effective competition at this level upholds the rules-based order, denies our rivals’ use of incremental coercion, and creates the space for American diplomatic, political, economic, and technological advantages to prevail over the long term.13 In short, it helps achieve the aim of line of effort 1, which is the promotion of maritime security and good maritime governance.

Examples provided in Advantage at Sea of “activities short of war” conducted by Navy and Coast Guard ships as part of day-to-day competition include:

- freedom of navigation operations globally to challenge excessive and illegal maritime claims;

- Coast Guard cutters and law enforcement detachments aboard Navy and allied ships exercising unique authorities to counter terrorism, weapons proliferation, transnational crime, and piracy;

- enforcing sanctions through maritime interdiction operations, often as part of international task forces;14

- crucial peacetime missions, including responding to disasters, preserving maritime security, safeguarding global commerce, protecting human life, and extending American influence; and

- underwriting the use of global waterways to achieve national security objectives through diplomacy, law enforcement, economic statecraft, and, when required, force.

Such activities support day-to-day competition in a diverse threat environment that includes potential adversaries such as Russia and China, but also additional state competitors, violent extremists, and criminal organizations, all of which exploit weak governance at sea, corruption ashore, and gaps in maritime domain awareness. Furthermore, “[p]iracy, drug smuggling, human trafficking, and other illicit acts leave governments vulnerable to coercion. Climate change threatens coastal nations with rising sea levels, depleted fish stocks, and more severe weather. Competition over offshore resources, including protein, energy, and minerals, is leading to tension and conflict. Receding Arctic sea ice is opening the region to growing maritime activity and increased competition.”15 These forces and trends create vulnerabilities for adversaries to exploit, corrode the rule of law, and generate instability that can erupt into crisis in any theater.16

If, as Advantage at Sea posits, the Naval Service will be called upon on a day-to-day basis to conduct operations short of war, the traditional functions assigned to the Coast Guard and Navy, respectively, as depicted in Figure 1, will become more integrated and homogenized.17 The Coast Guard will increasingly be called upon to conduct MSOs in the political-military realm, such as freedom of navigation operations, sanctions enforcement through maritime interdiction operations (often as part of international task forces), and providing specialized capabilities, to include Port Security Units or Advanced Interdiction Teams to augment operations in theater.18 The Navy, by contrast, will increasingly be called upon to conduct operations in the lower-threshold, “softer” constabulary realm. We know this to be so because: (1) Advantage at Sea and other strategic documents tell us so, and (2) as by far the largest seagoing service in an era of ever-shrinking platforms available to “employ All-Domain Naval Power to prevail across the competition continuum,” no other realistic alternative exists.19

For a variety of structural and other reasons, adaptation by the Navy to operate in the constabulary realm is much more challenging than the adaptation necessary by the Coast Guard to conduct higher-threshold political-military operations.20 Principal among the many challenges is the fact, as Professor Luke identifies, that legitimacy of operations short of war is the ultimate “measure” of their lawfulness. Legitimacy brings into play the vista of “legal regimes, treaties, and sources of authority that need to be fully appreciated, understood, and leveraged,” both individually and interrelatedly, to ensure the success of a contemplated lower-threshold operation. The unique nature of operations at this level, and the Navy’s capacity to adequately plan for them, is the subject of the next section in part 2 of this article.

Capt. (ret.) Andrew Norris works as a maritime legal and regulatory consultant, and has been retained to create and teach a new five-month maritime security and governance course for international officers at the U.S. Naval War College. He retired from the U.S. Coast Guard in 2016 after 22 years of service. Prior to attending law school and joining the Coast Guard, Capt. (ret.) Norris served in the U.S. Navy as a division officer aboard the USS KIDD (DDG-993) from 1985-1989. He can be reached at +1 (401) 871-7482 or [email protected].

References

[1] Tri-Service Maritime Strategy “Advantage at Sea,” 17 December 2020.

[2] Geoffrey Till, Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-First Century: Fourth Edition (New York: Routledge, 2018), 97.

[3] Navy Warfare Publication 5-01, Navy Planning (Ed. December 2013).

[4] Milan Vego, “Operations Short of War and Operational Art,” Joint Forces Quarterly 98 (3rd Quarter 2020): 38-49.

[5] Ivan Luke, “Naval Operations in Peacetime: Not Just “Warfare Lite,” Naval War College Review 66, no. 2 (Spring 2013): 10-26.

[6] See Figure 3, Appendix, in part 2 of this article.

[7] See, e.g., the mission statement of the State Department’s Office of Ocean and Polar Affairs (https://www.state.gov/bureaus-offices/under-secretary-for-economic-growth-energy-and-the-environment/bureau-of-oceans-and-international-environmental-and-scientific-affairs/office-of-ocean-and-polar-affairs/); Presidential Policy Directive (PPD)-8 (Maritime Security) and the underlying National Strategy for Maritime Security; and the 2019 Maritime Security and Fisheries Enforcement Act (or Maritime SAFE Act), a component of the 2019 National Defense Authorization Act.

[8] Professor Christian Bueger at the University of Copenhagen eponymously devotes an entire article to the issue of “What is Marine Security,” Marine Policy 53 (2015) 159–164.

[9] References to “threshold” and “spectrum” refer to the spectrum of violence as depicted in Figure 1, which also equates to the spectrum of activities across the competition continuum in Advantage at Sea.

[10] Article 29 of The Convention on the Law of the Sea, Dec. 10, 1982, 1833 U.N.T.S. 397 (UNCLOS) defines a “warship” as “a ship belonging to the armed forces of a State bearing the external marks distinguishing such ships of its nationality, under the command of an officer duly commissioned by the government of the State and whose name appears in the appropriate service list or its equivalent, and manned by a crew which is under regular armed forces discipline.”

[11] UNCLOS, Article 111.

[12] In general, “naval, coast guard, marine police, coastal and maritime forces are joined by ground and air elements of the joint armed forces, other departments and agencies, including oceanographic and fisheries services, the intelligence community, and international partners” to conduct maritime security operations.” James Kraska and Raul Pedrozo, International Maritime Security Law (Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff, 2013), 3.

[13] Advantage at Sea, 10.

[14] While forward-looking overall, in this respect, Advantage At Sea reflects existing realities: “Over the past decade, the Security Council has authorized the naval pursuit of rogue states, nuclear proliferators, pirates, and migrant smugglers with unparalleled frequency. From 1946 to 2007, the Security Council adopted approximately thirty-six resolutions with a direct or indirect impact in the maritime environment. In the following decade, from 2008 to 2017, the Security Council approved more than fifty such resolutions. What previously occurred about once every 1.7 years at [the United Nations] for six decades—the adoption of a resolution with a direct or indirect maritime impact—now is routine, transpiring every 2.5 months.” Brian Wilson, “The Turtle Bay Pivot: How the United Nations Security Council Is Reshaping Naval Pursuit of Nuclear Proliferators, Rogue States, and Pirates,” Emory International Law Review 33, issue 1 (2018): 1-90.

[15] Advantage at Sea, 5.

[16] Advantage at Sea, 5.

[17] For an excellent analysis of U.S. Navy versus U.S. Coast Guard functions, see Odom J.G. (2019) The United States. In: Bowers I., Koh S. (eds) Grey and White Hulls. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9242-9_11.

[18] Advantage at Sea, 13-14.

[19] Advantage at Sea implicitly recognizes this by its reference to the Coast Guard integrating its unique authorities—law enforcement, fisheries protection, marine safety, and maritime security—with Navy and Marine Corps capabilities (including the availability of assets) as a means of providing options to joint force commanders for cooperation and competition. Advantage at Sea, 7.

[20] The Coast Guard always has a focus toward higher threshold operations since, by law, it can be and has been (most recently, during World War Two) subsumed by the Navy in times of war. Thus, for example, the Coast Guard Atlantic and Pacific Area commanders continuously exist within DOD as Commander, Coast Guard Defense Force (CGDEFOR) East and West, respectively; federal law requires the Coast Guard to engage in training and planning of reserve strength and facilities as is necessary to insure an organized, manned, and equipped Coast Guard when it is required for wartime operation in the Navy; and Coast Guard doctrine recognizes the need to employ its authorities to support National Defense Strategy (NDS) objectives. See Coast Guard Strategic Plan 2018-2022.

Featured Image: May 2, 2021 – USCGC Hamilton (WMSL 753) and Georgian coast guard vessels Ochamchire (P 23) and Dioskuria (P 25) conduct underway maneuvers in the Black Sea. Hamilton is on a routine deployment in the U.S. Sixth Fleet area of operations in support of U.S. national interests and security in Europe and Africa. (Credit: U.S. Coast Guard)

We need to rethink current U.S. naval capabilities and apply them to the complexity of today’s evolving irregular operating environment – the Naval Criminal Investigative Service’ unique law enforcement, counterintelligence, counterterrorism, and cyber expertise must be leveraged to optimize conditions necessary to win the day-to-day competition and if necessary the high end fight as well.