By Daniel Kostecka

From 1923 to 1940, the United States Navy, sometimes in cooperation with other services, conducted 21 large-scale exercises known as Fleet Problems. These exercises were critical in developing tactics and operational concepts, along with the plans for platform development and acquisition crucial to the fleet’s success in the Second World War. Former Pacific Fleet commander, Admiral Scott Swift, recognized the important role played by the Fleet Problems in developing and training the fleet and revived them as a core component of fleet level training in 2016.

One of the most noteworthy exercises conducted by the U.S. Navy between the World Wars was Fleet Problem IX. Conducted in January 1929 in the waters off Panama, the primary purpose of the exercise was to evaluate the Panama Canal Zone’s vulnerability to attack from the sea. However, its place in history comes from the demonstration of the offensive potential of the aircraft carrier and airpower delivered from the sea. Yet Fleet Problem IX also demonstrated the vulnerability of aircraft carriers to what are today referred to as anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) threats.

In fact, the nature of the threats to the U.S. Navy’s aircraft carriers displayed during Fleet Problem IX are all too familiar to modern-day strategists wrestling with the difficult problem of how to cope with the increasingly sophisticated and diverse A2/AD systems fielded by China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) in the Western Pacific. The primary difference between 1929 and today is the sophistication and range of the weapon systems themselves, not the broader nature of the threats. Fleet Problem IX serves as an excellent starting point for understanding the vulnerability of aircraft carriers to the A2/AD threat.

A Fleet Problem IX

Fleet Problem IX was a truly massive exercise. Participating units included 67 percent of the aircraft carriers, 72 percent of the battleships, 38 percent of the cruisers, 68 percent of the destroyers, 40 percent of the submarines, and over 52 percent of the Navy’s combat aircraft, including planes from the Marine Corps. U.S. Army ground forces and aviation units participated as well. Fleet Problem IX assigned the Blue Force to defend the Pacific side of the Panama Canal while the Black Force was charged with attacking it.

The difference between Fleet Problem IX and previous exercises was the inclusion of modern large aircraft carriers. Previous exercises had included the small carrier USS Langley along with surface ships acting as stand-ins for carriers, but Fleet Problem IX included the two new and massive carriers USS Lexington and USS Saratoga.

Saratoga served as the centerpiece of the attacking Black Fleet along with nine battleships, a light cruiser, 36 destroyers (plus six constructive), and eight submarines (plus four constructive). To defend the Canal, the defending Blue Force assembled an impressive A2/AD system composed of USS Lexington, four battleships (each representing a division of three ships), five light cruisers, 29 destroyers, and 24 submarines, plus 5000 troops from the Army’s Panama Division, and approximately 50 land-based aircraft of all types and three seaplane tenders with attendant amphibious patrol planes.

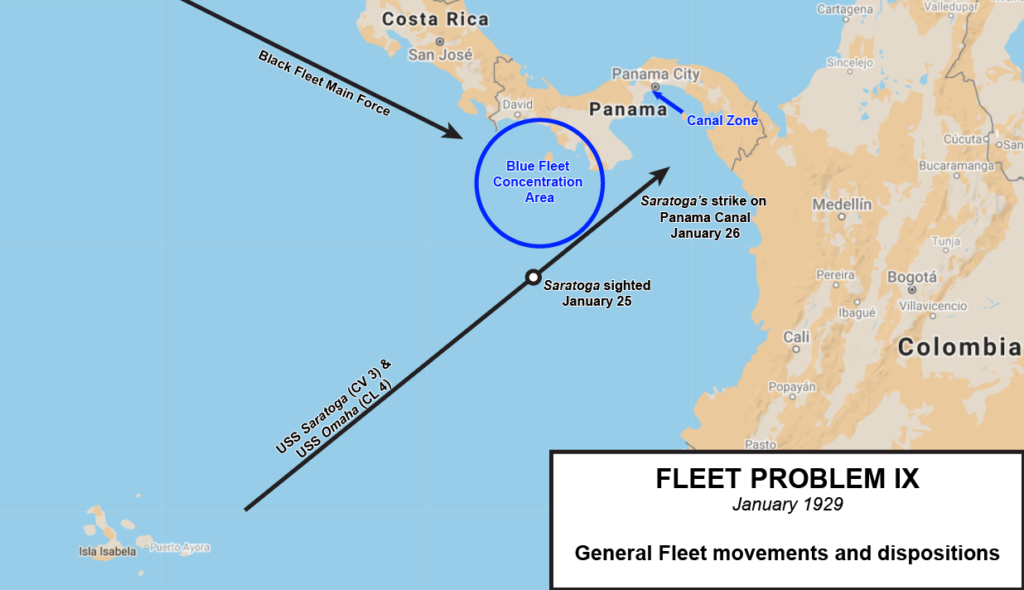

Vice Admiral William V. Pratt, commander of the U.S. Navy’s Battle Force and a future CNO, commanded the Black Fleet. The fleet began the operation at Magdalena Bay, Mexico roughly 3,200 miles northwest of Panama. Pratt authorized Rear Admiral Joseph Reeves onboard Saratoga, escorted by the light cruiser USS Omaha, to separate from the main force of battleships and make a high-speed run to the Galapagos Islands, and launch a surprise air attack on the locks of the Panama Canal from the southwest while the main task force made a direct approach from the northwest.

Before 0500 hours on January 26, Saratoga, operating 140 miles offshore, launched an 83-plane strike against the Panama Canal. The rest is written in the lore and mythology of naval history. Shortly before 0700 hours, Saratoga’s aircraft arrived over their targets, surprising the Canal Zone’s sleepy defenders, and executing what would have been a crippling strike on the Canal’s Miraflores and Pedro Miguel Locks and Army facilities at Fort Clayton and Albrook Airfield.

The offensive potential of the aircraft carrier was clear. Vice Admiral Pratt stated after the exercise, “I believe that when we learn more of the possibilities of the carrier, we will come to an acceptance of Admiral Reeves’ plan which provides for a very powerful and mobile force.” The Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet, Admiral Mark Wiley said, “No single air operation ever conducted from a floating base speaks so eloquently for the advanced state of development of aviation as an integral part of the Fleet.” Pratt even honored Saratoga and her crew by transferring his flag to the carrier for the return to the United States.1

However, while the overall truth of the statements by Admirals Wiley and Pratt is beyond dispute, Fleet Problem IX also displayed the vulnerability of aircraft carriers in addition to the offensive potential of sea-based airpower. This is because while Saratoga’s aircraft did launch a successful attack on the Panama Canal, the Blue defenders’ A2/AD system had its own share of victories.

The Blue Forces scored their first successes on January 25 when Blue intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) assets detected Saratoga and Omaha as they approached the launch point from the direction of the Galapagos Islands. The Blue commander, Vice Admiral Montgomery Taylor, deployed two groups of destroyers to cover the approaches to Panama and at 1613 hours on January 25 the destroyer USS Breck struck paydirt when it found Reeves’ carrier.

Breck was quickly dispatched by USS Omaha and by gunfire from Saratoga herself, but she managed to send a position report. Two hours later the light cruiser USS Detroit found the carrier and her escorting cruiser. While Detroit suffered the same fate as Breck, the Blue defenders were now aware of Saratoga’s location and course and the fact that she was operating independently of the main Black Fleet.

While Saratoga was still able to launch her strike against the Panama Canal the next morning, less than two hours after her planes were in the air, she encountered three battleships from the Blue Fleet. With no aircraft aboard to defend her she was ruled sunk by gunfire. For good measure, shortly afterwards a Blue submarine fired a spread of four torpedoes against Saratoga at 1200 yards and she was declared sunk for the second time in less than an hour.

An hour later, planes from Blue’s carrier, USS Lexington, arrived and attacked as Saratoga was recovering aircraft from the strike against the Panama Canal. The exercise umpires determined she would have at least been badly damaged. Saratoga and her crew were spared a fourth “sinking” when Blue torpedo bombers from VT-9, operating out of the seaplane base at Balboa, attacked their own carrier, Lexington—an easy mistake given that the two sister carriers were only separated by 12 miles at the time.

Saratoga’s experience with the Blue Force defenders during Fleet Problem IX highlights the dangers of attacking a diverse and layered A2/AD defensive system. No single aspect of Vice Admiral Taylor’s ISR and defensive networks were sufficient, but the varied and multilayered nature of the system he deployed ensured some degree of success. Blue’s reconnaissance aircraft failed to find Saratoga, but Taylor’s scouting destroyers filled the gap and the Blue Fleet’s submarines were on the prowl as well.

After she was detected, it is possible any one of the varied attacks against Saratoga would have failed. Saratoga had a 12-knot speed advantage over the battleships that “sank” her on January 26. Perhaps she could have run from them and it is entirely possible the submarine torpedoes fired at her would have missed. Rear Admiral Reeves himself claimed that in wartime he could have run from Vice Admiral Taylor’s forces and taken the loss of his air group as acceptable casualties in exchange for damaging a strategic target, but peacetime safety requirements necessitated remaining in position to recover his aircraft.

Theoretically, Lexington’s aircraft should not have been able to attack Saratoga because Lexington herself had run afoul of the Black Fleet’s battleships the day before but was only ruled “damaged” by the umpires in order to maintain her participation in the game. However, had Lexington been knocked out of the game on January 25, then VT-9’s torpedo bombers would not have mistaken her for Saratoga and likely would have attacked their intended target instead. The point is the redundant nature of the ISR network and A2/AD system deployed by the Blue Force meant that to get within range of the Panama Canal, Saratoga entered a hornets’ nest of threats where her detection and destruction were highly likely, if not guaranteed.

Lessons for Today

Submarines, surface ships, and land and carrier-based aircraft were all part of a sophisticated A2/AD system assembled by the Blue Fleet during Fleet Problem IX. That each of these capabilities administratively sank or damaged USS Saratoga at different points during Fleet Problem IX demonstrates the value of a multi-faceted and layered A2/AD system for opposing aircraft carriers. It is therefore not surprising that each of these capabilities form components of the A2/AD system that China is developing to oppose the U.S. Navy’s carrier strike groups in the Western Pacific should conflict ensue.

China’s PLAN is an increasingly modern and flexible force capable of conducting a wide range of peacetime and wartime operations at expanding distances from the Chinese mainland. With an overall battle force of over 360 ships, including more than 130 major surface combatants and more than 60 submarines, along with its own aviation arm of more than 300 land- and sea-based aircraft of all types, the PLAN is the largest navy in the world. However, it is as an A2/AD force organized, trained, and equipped to oppose U.S. combat operations in East Asia and the Western Pacific that the PLAN is at its most dangerous.

Just as a Blue Fleet submarine claimed USS Saratoga during Fleet Problem IX, PLAN submarines would be at the forefront of any Chinese attempt to deny key operating areas in the Western Pacific to the U.S. Navy. The PLAN submarine fleet consists of 50 conventionally-powered and six nuclear-powered attack submarines, 44 of which are armed with long-range anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs), including eight Russian built Kilos armed with the SS-N-27B (120nm range) and 36 Song, Yuan, and Shang-class submarines armed with the 290nm range YJ-18.

It is no accident that a submarine administratively “sank” USS Saratoga during Fleet Problem IX or that the same aircraft carrier was heavily damaged and “mission killed” twice by Japanese submarines in 1942. Submarines have always presented a substantial threat to aircraft carriers, and with sophisticated long-range missiles and patrol patterns reaching out into disputed waters in East Asia and the Indian Ocean, often within range of U.S. assets, PLAN submarines represent a formidable threat to American aircraft carriers today. Combined with the multilayered ISR assets of an A2/AD network, submarines could be cued to launch long-range anti-ship missile salvos from unexpected vectors and at much lower risks to themselves compared to a closer-range torpedo attack.

While surface ships are not normally thought of as a threat to aircraft carriers due to the long reach of the carrier’s air group, that paradigm may be changing. During Fleet Problem IX and during the 1920s in general surface gunfire was a threat to aircraft carriers due to the short range of carrier aircraft and the lightness of their weapons. Even during the Second World War surface ships occasionally caught carriers, such as HMS Glorious, flat-footed. However, today it is the long range of the missiles employed by some surface ships that make them a threat to aircraft carriers, particularly in the opening stages of a conflict before before ships have had a chance to transition from an open deterrence posture to a more evasive wartime operating pattern.

The PLAN currently possesses over 120 corvettes, frigates, destroyers, and cruisers armed with long-range ASCMs, along with approximately 60 fast missile patrol combatants. Included in this impressive array of surface combatants is the new Luyang III-class guided missile destroyer equipped with a ship-launched variant of the YJ-18 and the new Renhai-class guided missile cruiser also equipped with the YJ-18 and potentially a long-range anti-ship ballistic missile in the future. That a surface task force of the PLAN operated in the Central Pacific in January and February 2020 suggests the PLAN intends to use its ASCM-armed ships to expand its A2/AD envelope to guarantee its maritime security. The need to do so was stated by the PLAN’s Rear Admiral Zhang Zhaozhang in April 2009, “Only when the Chinese navy goes beyond the First Island Chain, will China be able to expand its strategic depth of security for its marine territories.”2

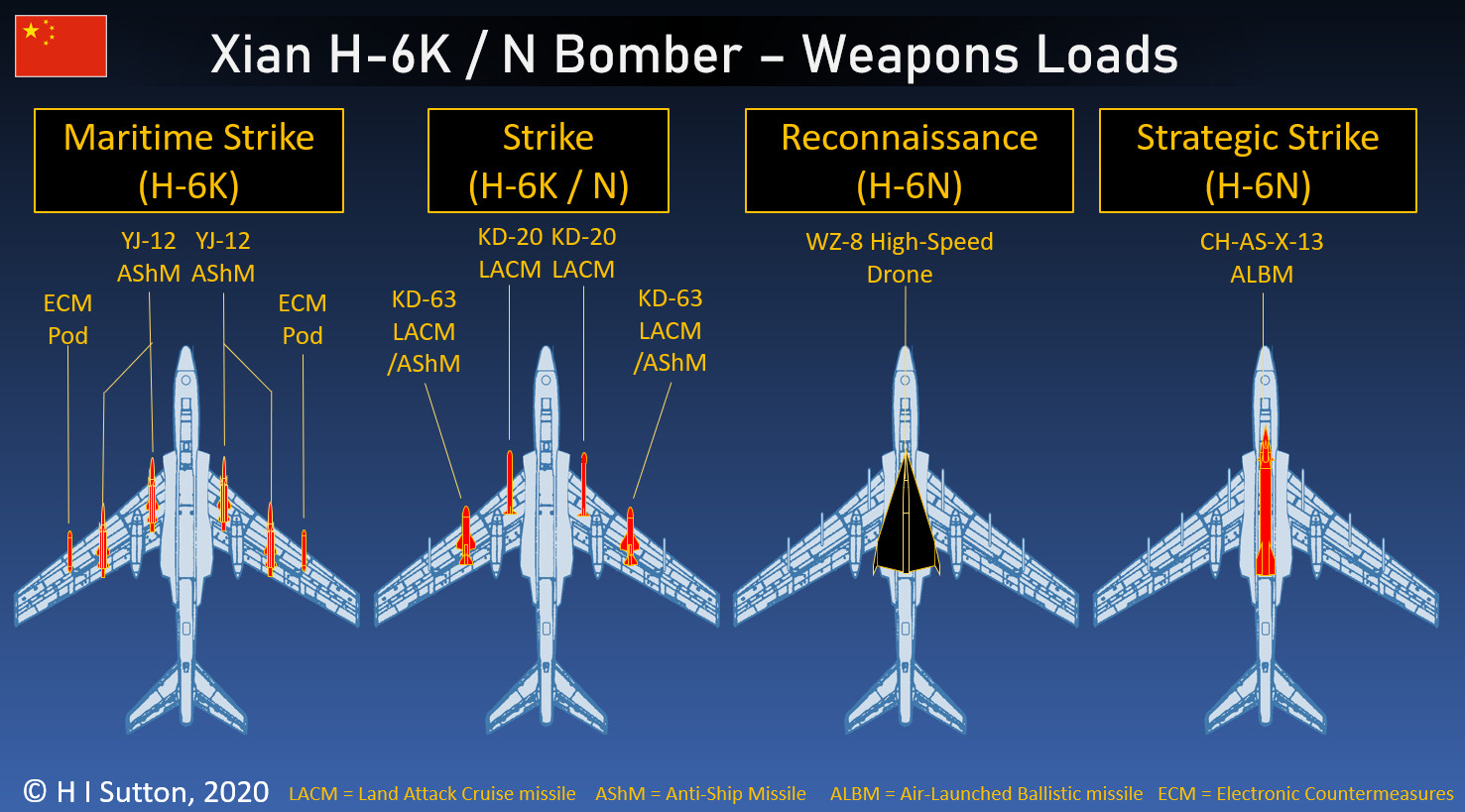

Blue Force land- and carrier-based aircraft were a substantial part of Vice Admiral Taylor’s A2/AD system during Fleet Problem IX and they play a substantial role for the PLAN today. The PLAN fields five regiments of JH-7 maritime strike-fighters armed with the YJ-83K ASCM, two regiments of long-range H-6 bombers capable of employing the supersonic YJ-12, and one regiment of modern Russian-built Su-30MK2 Flanker strike-fighters equipped with the Kh-31 air-to-surface missile. The PLAN also operates two aircraft carriers and is building a third.

While the PLAN’s two operational carriers are less capable offensive strike platforms than U.S. Navy carriers due to their ski jump launching mechanism instead of catapults, PLAN carriers could still play a key role in its A2/AD system. This is because even with airborne tanking, land-based Chinese fighters would still be hard-pressed to establish a persistent presence hundreds of miles from the Chinese mainland and provide cover for surface ships and long-range maritime strike aircraft. However, carrier-based fighters could provide air defense to PLAN surface ships and bombers, enabling them to get within weapons range of U.S. Navy carriers.3 As demonstrated by Fleet Problem IX, the success of an A2/AD system is based on redundant and complementary capabilities as opposed to any one single silver bullet.

In addition to the PLAN’s air, surface, and subsurface capabilities, another key component in China’s A2/AD systems are the land-based anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs) of the PLA’s Rocket Force (PLARF). A modern and extremely long-range take on an old maritime defensive system, coastal artillery, these weapons present an A2/AD threat unimaginable in the 1920s. The first ASBM fielded by the PLARF is the 810nm range DF-21D, operational since 2010. A new system, the DF-26 with a range of 2,100nm, is in the process of becoming operational and will be able to threaten U.S. aircraft carriers operating east of Guam.

Fleet Problem IX also demonstrated the necessity of effective ISR to an A2/AD system. Vice Admiral Taylor deployed an array of ships, submarines, and reconnaissance aircraft to ascertain the movements of the Black Fleet. China is doing the same today in the Western Pacific. PLAN surface ships regularly patrol East Asian waters, and their operating areas are expanding into the Central Pacific and the Indian Ocean. Also patrolling regional waters are cutters from the China Coast Guard (CCG, like the PLAN the world’s largest) and numerous ships from local Chinese Maritime Militia forces. China has also launched new surveillance satellites that will bolster its maritime domain awareness.

It is possible if not likely that during a time of tension or in the run up to a crisis that U.S. Navy carrier strike groups operating in the Western Pacific will be shadowed by Chinese tattletales from the PLAN, the CCG, or Maritime Militia and could perform a similar role as the Blue Fleet destroyer that relayed the position of Saratoga. PLAN submarines will also play a substantial ISR role during any conflict and the PLAN’s growing fleet of special mission aircraft based on the Y-8/Y-9 airframe satisfy key maritime patrol and ISR requirements.

A crucial element of this overlapping ISR system of systems is the land-based skywave over-the-horizon radar (OTH), a growing array of reconnaissance satellites, and civilian maritime monitoring systems that contribute to China’s maritime situational awareness. The PLA’s weapons require a robust and redundant OTH targeting capability to be employed at long ranges. China’s investment in ISR along with the necessary command and control systems is designed to provide essential targeting information to airborne, surface, sub-surface, and land-based systems.

Conclusion

Fleet Problem IX—an exercise conducted almost a century ago—is still instructive for naval strategists, tacticians, and planners today. While it is remembered, and rightly so, for demonstrating the offensive potential of the aircraft carrier, it also demonstrated their vulnerability, particularly when the adversary presents an opposing carrier fleet with a multi-layered A2/AD system consisting of complementary capabilities.

During Fleet Problem IX, the Blue Force commander Vice Admiral Taylor devised such a system to oppose the Black Fleet in defense of the Panama Canal. Today, China has built and is steadily improving a similar system in the Western Pacific. However, the overall design and construct of China’s A2/AD system of today is hardly much different than that developed and deployed by Vice Admiral Taylor for Fleet Problem IX. It is in this way that studying Fleet Problem IX provides enduring lessons for understanding the anti-access dilemma.

Daniel J. Kostecka is a senior civilian analyst for the U.S. Navy and has worked for the Navy for 16 years. He has also worked for the Department of Defense and the Government Accountability Office. He was an active-duty Air Force officer for ten years and recently retired from the Air Force Reserves with the rank of lieutenant colonel and over 27 total years of commissioned service. Mr. Kostecka has a bachelor of science in mathematics from The Ohio State University, a master of liberal arts in military and diplomatic history from Harvard University, a master of arts in national security policy from the Patterson School of Diplomacy and International Commerce at the University of Kentucky, and a Master of Science in strategic intelligence from National Intelligence University. Mr. Kostecka is also a graduate of Squadron Officer School, the Air Command and Staff College, the Air War College, and Joint Forces Staff College. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense.

Endnotes

[1] Gerald E. Wheeler, Admiral William Veazie Pratt – A Sailor’s Life. Washington, DC: Naval History Division, 1974, pp 275.

[2] Cai Wei, “Dream of the Military for Aircraft Carriers,” Sanlian Shenghuo Zhoukan, 27 April 2009.

[3] Cui Changqi, Ed, Air Raid and Anti–Air Raid in the 21st Century, Beijing: People’s Liberation Army Press, 2002.

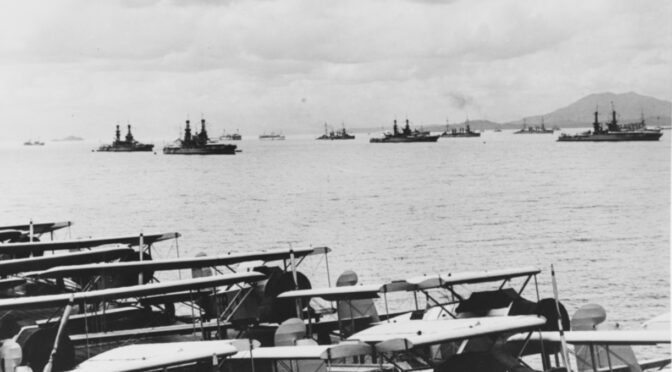

Featured image: Battleships and other ships of the U.S. Fleet at anchor in Panama bay on 26 February 1929 at the completion of that year’s fleet problem. Photographed from USS Lexington (CV-2).

These developments show an increasing shift from emphasis on sea targets to those from the Chinese Mailnland- since that is from where the missiles will come. That means no “limited war”.

Bingo. If the sea is to become a no man’s land for any surface ship. It will be the mainlands of each country trading shots.