Guest post for Chinese Military Strategy Week by Jack McKechnie

The People’s Republic of China’s new Military Strategy white paper indicating China’s military strategy is a positive step towards transparency, but comparison with the recent U.S. National Military Strategy (NMS) reveals a significant difference and ominous implications of future paths. Should China and the U.S. pursue their stated military strategies, a period of increasing tension and force buildup will ensue as the U.S. and allies seek to maintain an absolute advantage over a rising Chinese regional advantage. While the national leaderships of China and the U.S. will likely strive to avoid the use of force, miscalculations can occur and attempts at reassurance can fail with severe, complicating, and long-lasting consequences for everyone involved. A future strategy by China that reassures the rest of the world that its rise is peaceful is necessary to avoid this situation.

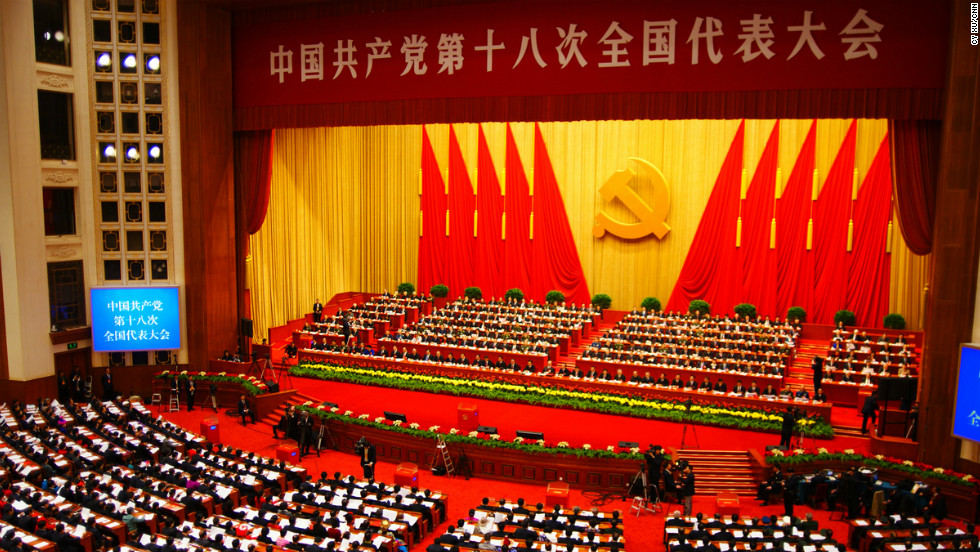

Although both documents appear to portray each country’s military strategies, there is a key difference that makes this an imperfect comparison. While the U.S. president is both commander-in-chief of the U.S. military as well as party chief of his political party, the U.S. military is not a party army, and the U.S. NMS has no mandate to keep the Democratic Party in power. Xi Jinping is both chairman of the China’s central military commission as well as general secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC), but the PLA is a party army, and the PRC defense white paper declares that “China’s armed forces will unswervingly adhere to the principle of the CPC’s absolute leadership” and “remain a staunch force for upholding the CPC’s ruling position.”

The PRC defense white paper articulates a response to security threats to the CPC, not China, and there are circumstances in which a move benefitting the CPC does not benefit China. A fixation to remain in power and a tendency to exaggerate threats to party rule may lead the CPC to assume a more aggressive posture resulting in higher risk of conflict than the actual security threat to China would justify. The risk of a serious conflict, which would be devastating for the Chinese people, warrants consideration of an assuring and less threatening stance instead. The CPC’s aggressive rhetoric regarding Taiwan, Japan, and the South China Sea may be intended to bolster domestic support for the CPC, but should miscalculation and conflict occur, the impact to China’s growth could be severe. Ironically, these economic consequences of conflict may cause the CPC to face a primary concern, disorder at home, and which they may hope to forestall by rallying their populace with assertive foreign policy.

From the perspective of the CPC, this makes reassurance and the avoidance of miscalculation critical, but the difference in objective for the PRC defense white paper contributes to difficulties in reassuring the U.S. and other countries that China’s rise will remain peaceful. The U.S., distrustful of authoritarian governments and wary of attempts to unilaterally disrupt the international order by a rising power, would need enhanced reassurances from China.

Dale Copeland describes the commitment problem as the inability of one state’s leadership to convince another state’s leadership that promises made today will be kept. In this case, the U.S. may not only be concerned that China may have a change of heart later once they have more relative power, but also that new leaders in China may adopt very different policies.1 Ambiguity in the PRC defense white paper regarding how they intend to safeguard Chinese maritime interests and address the issue of Taiwan fails to ease the U.S. and regional states. And while principles of defense, self-defense, and post-emptive strike are declared, other countries have little assurance that these principles will be adhered in the future.

The ambiguity in the PRC’s strategy, in conjunction with an alarming, sustained military buildup at a time when China’s mainland has never been safer from invasion, may be construed as a more or less direct contradiction of reassurances that China does not pose a security threat. Neither the U.S. nor the Chinese military strategy explicitly discusses force posture, but the fact that the U.S. is transparent with products such as the U.S. Navy’s 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan to Congress, a document that describes long-term future fleet composition, while China has no overt guidance for their desired size for their rapidly-growing military does give cause for concern by the U.S. and the rest of the world.

The strategies executed together produce the conditions for an Asia-Pacific Cold War in the future security environment as described by a report by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: “Deepening regional bipolarization and militarization, driven by a worsening U.S. – China strategic and economic rivalry in Asia.”2 Arms races, military crises, and increasing tension regarding Taiwan reunification could result in a period of constant tension while the U.S. and regional allies balance the increase of Chinese capabilities to preserve an absolute advantage that, they hope, deters conflict. China’s lack of articulation regarding the intended future size of their military and the failure to provide reassurance for exclusively peaceful means to handle their concerns with Taiwan, Japan, and with other claimants in the South China Sea do not reassure the U.S. and other countries, and the likely result will be continued arms build-up and increasing tensions.

The deliberate use of lethal force by China in pursuit of territorial claims, whether for a coercive reunification of Taiwan or establishment of solid control over the nine-dash line, will result in dramatic changes around the world. A loss of confidence in Asia will cause multiple, independent actors to react in unforeseen ways which may have a dramatic effect on Asian commerce. Moreover, the CPC may not understand the potential resolve of the U.S. and other democracies to resist lethal aggression and what actions they may take against China and what consequences, economic and otherwise, they are willing to impose. While growth and stability of the entire world would be profoundly affected, China, with its high growth dependence on foreign trade and commerce, could face the most serious consequences. The results within China would ironically jeopardize the social and political order the CPC may have used to justify aggression in the first place.

To best serve the security interests of China and maximize economic potential while minimizing threat of war, there are measures the CPC might pursue to assure the rest of the world while remaining in power. As stated by James Steinberg and Michael O’Hanlon, China can better reassure the U.S. and regional countries by leveling military budget growth at approximately half of the U.S. level and scaling back missile deployments and other military capacities directed at Taiwan, commit to exclusively peaceful means towards Taiwan, and join in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Code of Conduct with a commitment not to use or threaten force to resolve territorial disputes.3 As a revisionist power, assurance is incumbent on the Chinese, and only positive measures such as these will provide the necessary assurance to regional and global powers that China’s intent is peaceful and will minimize the risk of miscalculation and the associated social, economic, and military consequences.

Jack McKechnie is a Commander in the U.S. Navy currently assigned to the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. He was a former U.S. Seventh Fleet operational planner, Japan country officer, and assistant director for theater security cooperation from Oct 2011 to July 2014 and a Federal Executive Fellow with Johns Hopkins University APL from Aug 2014 to July 2015. The views expressed in this article are his own.

[1] Dale Copeland. Economic Interdependence and War (Princeton University Press, 2015), 41.

[2] Michael Swaine et al. Conflict and Cooperation in the Asia-Pacific Region: A Strategic Net Assessment (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington D.C., 2015) 167.

[3] James Steinberg and Michael O’Hanlon. Strategic Reassurance and Resolve: U.S. – China Relations in the Twenty-First Century (Princeton University Press, 2014), 209-210.