Military planners have historically used wargames to influence future operations. The extensive wargaming conducted at the U.S. Naval War College during the interwar years is widely credited with preparing the Fleet to fight one of the greatest seaborne wars in history against Japan during World War II.

As Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz put it: “War with Japan had been reenacted in the game rooms at the Naval War College by so many people and in so many different ways, that nothing that happened during the war was a surprise…absolutely nothing except the kamikaze tactics toward the end of the war; we had not visualized these.”

The iconic images of War College students maneuvering model fleets across the wargaming floor of Pringle Hall as the players experimented with scenario after scenario are staples for any student of naval history. Since then, technology and computers have greatly improved the process, and the War College is arguably still the world’s premier wargaming organization, providing key insights to fuel operational planning and acquisition. Unfortunately, as extensive and sophisticated as its program is, it can only perform about 50 events each year. Facility space, equipment availability, and personnel to actually play the games will always constrain the robustness of on-site wargaming programs…at least for now.

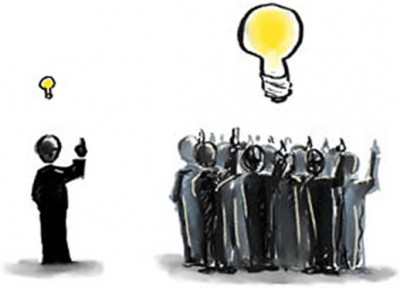

What if all resource constraints were removed from our wargaming activities? What if an infinite amount of space was available – only limited by the surface of the Earth? What if the potential participants were only limited by a population willing and able to participate? What if they were equipped with the resources necessary to execute a war game? These questions might seem absurd at first, but a new and powerful concept known as crowdsourcing could be the answer to solve these resource issues.

No longer a notional concept, crowdsourcing is becoming more widespread. The basic idea is to leverage the collective intelligence and creativity of the “crowd” – a large, virtually limitless population. Advances in collaborative technologies have helped commercial entities leverage this concept and vastly increase productivity. One of the more well-known is the Amazon Mechanical Turk which, at last count, had more than 500,000 participants in more than 190 countries all simultaneously completing simple tasks. Another is CrowdFollower, which claims to be able to access more than 2 million participants across the globe. Even complex strategic analysis from a crowdsourcing consultancy like Wikistrat is being done today.

How can this be applied to wargaming though? Given current processing power and infrastructure, it is not feasible for the crowd to submit traditional wargaming moves to a central hub (such as the War College) for adjudication. Instead, this broadening of the talent pool enables more ideas to effectively put the crowd to work. A starting point has been established by the U.S. Navy Warfare Development Command (NWDC), where they have conducted Massive Multiplayer Online War Game Leveraging the Internet (MMOWGLI) sessions that seek creative ideas to mission requirements across the active, reserve and civilian forces.

Crowdsourcing traditional wargames (such as those at NWC) in this way, would seek solutions to strategic, operational, and tactical problems while coupling realistic analysis with user-friendly interface necessary to enable an end-to-end scenario played by participants. The balance between the level of fidelity required to provide meaningful data, with the level of abstraction necessary to enable experimentation would be a key attribute. After processing of the information, these game results could reveal meaningful insights for tactical development.

As demonstrated in the interwar period, iteration after iteration of experimentation in wargaming can help predict possibilities in war and then provide at least a starting point to begin to prepare. Today, technology is advancing at rates never dreamed of prior to WWII, while geopolitical shifts are much more rapid and pronounced. The necessity for speed of iteration and experimentation has never been greater, and the crowd has the potential to help address this. Instead of roughly 50 war games each year, imagine hundreds – even thousands – played daily. The crowd can win and lose wargame scenarios over and over, rapidly resetting and fighting again. Combined with near-instant social media exchange of ideas, innovative solutions can emerge through pure trial and error from a group almost unimaginably large.

The world will always lean on experts. The crowd will most likely never replace the great wargaming work conducted at war colleges and throughout the military, but it has the potential to be a powerful source of rich data. The crowd is moving into formation, preparing to sail into war. Will we use the crowd or waste this virtually untapped resource? The time is coming to send the crowd to war.

LT Jason H. Chuma is a U.S. Navy submarine officer who has deployed to the U.S. 4th Fleet and U.S. 6th Fleet areas of responsibility. He is a graduate of the Citadel, holds a master’s degree from Old Dominion University, and has completed the Intermediate Command and Staff Course from the U.S. Naval War College. He can be followed on Twitter @Jason_Chuma.

The opinions and views expressed in this post are his alone and are presented in his personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy.

Time for a somewhat different

Sorry–unintended post there.

There is a disturbing undercurrent of technological triumphalism at play (pun intended) in some who equate wargaming with computers. Computers have done much to advance the state of the art in gaming, but on the whole, their main contribution has NOT lain in the realm of making better games on the computer. Wargaming is about people making decisions and in so doing creating a shared and interactive narrative. The wargame resides not in its instrumentality–whether crude ship models on a Naval War College game floor, cardboard counters on a paper hexagon map, or merely paper and pencil. The game is in the minds of the players. When computer or other technology helps facilitate and leverage that fact, it is Good Thing. When computer or other technology substitutes the perspectives of the systems programmer about what is important for the perspectives of the game players, it is Not So Good.

Wargaming’s power and success (as well as its dangerous potential for increasing self-delusion) derive

from its ability to enable individual participants to transform themselves by

making them more open to internalizing their experiences in a game—for good

or ill. The particulars of individual wargames are important to their relative success,

yet there is an undercurrent of something less tangible than facts or models

that affects fundamentally the ability of a wargame to transform its participants.

Wargaming’s transformative power grows out of its particular connections to storytelling;

gaming, as a story-living experience, engages the human brain, and hence the human being participating

in a game, in ways more akin to real-life experience than to reading a novel or

watching a video. By creating for its participants a synthetic experience, gaming

gives them palpable and powerful insights that help them prepare better for

dealing with complex and uncertain situations in the future. It is

the use of gaming to transform individual participants—in particular, key decision

makers—that is the most important, indeed essential, source of successful organizational

and societal adaptation to that uncertain future.

This is what made the NWC wargames of the 20s and 30s so important to the USN during World War II. What Nimitz said about everything but the kamikaze’s being played at Newport was correct; what he didn’t point out was all that was played incorrectly. The models were frequently wrong in their assessments of weapon capabilities (the Japanese Long Lance torpedo being the most egregious case). But the physical accuracy of those models was far less important than the shared experience of the players in dealing with a thinking human opponent trying very hard to beat their brains out. And in the habits of mind and decisionmaking those experiences helped inculcate.

Internet moderated crowd sourcing has proven useful for several things. Real wargaming (unlike MMOWGLI, which was an interesting technique for generating ideas but hardly a wargame in the classical sense of the word) may even evolve to make better use of that technology. Before that happens, however, we must think more critically about what it might be useful for, how best we might employ it, and how we can avoid dangerous self-delusion when interpreting its results. Just because it’s on the computer doesn’t make it right. Just because the “crowd” has danced down a particular path doesn’t mean it won’t lead to the edge of a cliff.

Dr. Perla. I am personally honored that you would even respond to my post. I am disappointed in my own writing that you felt my article was so techno-centric at the cost of the human element. It was not meant to mean that “computers will save us.” Wargaming is and has always been about two or more thinking and adapting opponents trying to win. Whether that takes place on a hex board rolling dice for interactions or a computer model instantly looking up probability tables, the importance is the human experience. In my opinion, computer versus computer is essentially useless, human versus computer is slightly better, but human versus human is where the real effectiveness lies. Both in terms of idea generation, and in terms of the player experience gained.

The crowdsourced results absolutely may not be correct, but also can the results of the more manual wargames played today. No theoretical solution should ever be assumed to be absolutely correct. We should not abandon all of the great wargaming done at places like the NWC and CNA because we are afraid someone will assume the results to be absolutely true simply because it came from a respected organization, and so to should we not abandon crowd generated results because we are afraid of the same thing. If you blindly follow anyone down a cliff you deserve to fall off of it.