The following two-part series will analyze the maritime dimension of competition between Ukraine and Russia in the Sea of Azov. Part 1 analyzed strategic interests, developments, and geography in the Sea of Azov along with probable Russian avenues of aggression. Part 2 will devise potential asymmetric naval capabilities and strategies for the Ukrainian Navy to employ.

By Jason Y. Osuga

Three Approaches to Building a Credible Deterrent

The primary job of any country’s military is to defend the nation from foreign attacks. The Ukrainian military must prevent further encroachment of its territory by Russia. Ukraine should consider three approaches to its nation’s defense. First, Ukraine should develop an effective asymmetric navy and coastal defense to counter the much stronger Russian conventional navy. An asymmetric navy can disrupt naval operations of a conventional fleet through the use of guerrilla tactics at sea. An asymmetric navy is also cheaper to build compared to a conventional navy which requires an enormous amount of resources and time to build. All these efforts could prove futile against a greater and stronger-willed adversary intent on defeating Ukraine in war. However, if Ukraine is able to raise the potential costs and increase enough risk, Russian leadership may think twice about conducting further encroachments on Ukrainian sea and land territories.

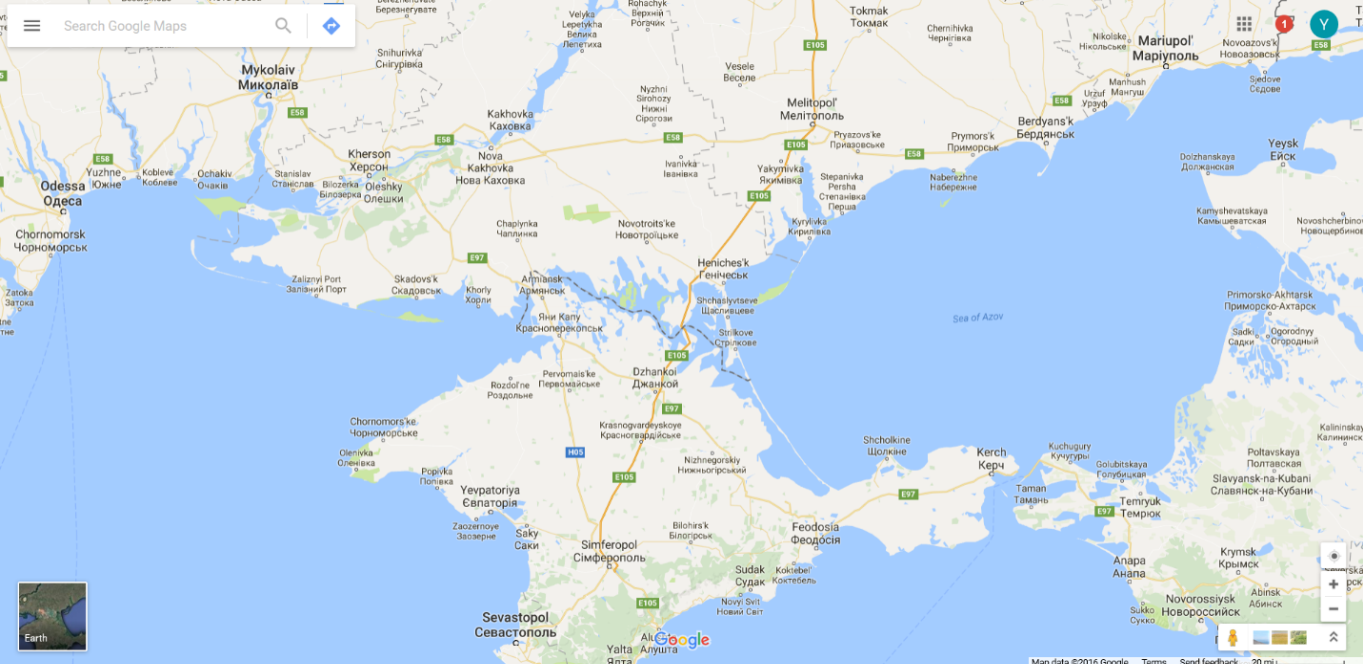

Second, the Ukrainian Navy and Army must adopt a joint strategy of conducting sea denial operations against Russian attempts to gain sea control. The Army and Navy must develop a joint sea denial doctrine and train together to prevent Russian forces from achieving sea control and chokepoint control of Kerch Strait. Ukraine’s sea denial strategy should focus on attacking the Russian center of gravity (COG) by weakening the functions that enable the COG to operate. Finally, the Ukrainian Navy should consider establishing a naval base in Mariupol and forward-deploying part of its fleet to the Sea of Azov (SOA). The patrol fleet would act as a deterrent against Russian encroachment in eastern Ukraine. Forward-basing cuts down on deployment time from Odessa, Ukraine’s only naval base of any significance following the loss of Sevastopol. Ukraine should also set up supply depots along the Azov coast to mitigate vulnerability of a singular dependence on Mariupol.

Asymmetric Naval Forces and Guerrilla Warfare at Sea

The backbone of an asymmetric navy is a sizeable fleet of small patrol crafts, missile boats, and mine-laying vessels. Small boats are necessary for speed and presenting a small target for the adversary. Hence, a large quantity of small boats is necessary to present a challenge through a swarm effect. During the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s, Iran learned that large naval vessels are vulnerable to air and missile attacks from a conventionally superior foe, which confirmed the efficacy of small boat operations and spurred interest in missile-armed fast-attack crafts (FAC).1 Iran expanded the use of swarm tactics that formed the foundation of its approach to asymmetric naval warfare.2 Investment in an asymmetric navy composed of small craft is more cost-effective compared to building large surface combatants in addition to presenting a more elusive target. The shallow water environment precludes friendly or enemy deep-draft capital warships and submarines from operating in the SOA. It is the shallowest sea in the world with a mean depth of just 10 meters. Just as Iran developed asymmetric tactics to deal with a larger and more sophisticated U.S. Navy, so can Ukraine develop asymmetric tactics against a larger and more sophisticated Russian Navy.

For defense of the SOA, the Ukrainian Navy should consider investing in Anti-Surface Warfare (ASUW), Coastal Defense (CD), Mine Warfare (MIW), and military pay, housing, and training.

Anti-Surface Warfare (ASUW)

The Ukrainian Navy should focus on building numerous anti-ship cruise missile (ASCM)-capable Patrol Boats (PB), Patrol Crafts (PC), and Guided-Missile Patrol Crafts (PTG). These small boats form the backbone of an asymmetric navy. Speed is a key requirement for these small boats to be able to employ shoot-and-scoot tactics. These vessels must be able to achieve minimum of 35 knots sustainable speed. In addition, these vessels must have long endurance to remain at sea for long periods of time. Frequent return to home-port to resupply makes the vessels more vulnerable. Therefore, vessels must have large storage capacity for provisions and fuel, relative to the size of the expected operating environment. To take on provisions, small crafts should be able to operate from inlets and small ports along the Azov coast. Therefore, another critical requirement is a low draft to operate in the SOA. Another potential solution could be small Rigid Hull Inflatable Boats (RHIB)-like crafts with powerful outboard engines. These 11-meter boats are capable of high speed, low draft, and are suitable for calm seas operations in the SOA. Under the Foreign Military Sales program in 2015, the US Navy delivered five 7/11-meter RHIBs produced by Willard Marine.3 This transfer fulfills speed and low draft requirements in the shallow littorals. Ukraine should continue to build a more robust surface patrol capability.

Maintenance, crew manning, and armaments are other important considerations. The future asymmetric fleet must be easy to maintain by using interchangeable parts that already exist in Ukraine’s defense infrastructure. Crew manning should be minimal to allow for crew rotation, training conducted on similar platforms, and manned by small increases to the overall manning level of the Ukrainian Navy. As for armaments, vessels should have 57-mm or 30-mm gun for self-defense and fire support, and perhaps .50 caliber (12.7mm) crew-served weapons for future interoperability with NATO.

These vessels’ main armament, however, should be ASCMs due to their longer range and lethality. The Ukraine Navy should incorporate the newly developed Neptune missile system on PCs, PTGs, and PBs when it passes all operational testing and evaluations.4 The two Gurza-M class armored patrol boats introduced to the Navy in 2015, with a further 20 planned by 2020, is a promising step in the right direction.5 However, these boats should have an ASCM capability. Otherwise, these new vessels risk being out-gunned and out-ranged. Such vessels would only be capable of conducting law enforcement operations in peacetime but inadequate in conducting sea denial operations in war.

Another area of needed attention is the modernization of C4ISR, strengthening cyber networks, and growing a professional cyber force in the Ukrainian military. All the investments in asymmetrical hardware would not be completely effective in combat unless they are tied to a modern, resilient battle network. Ukraine must elevate cyber to strengthen networks and the C2 of the fleet. The U.S. should provide training and support to standing up Ukrainian cyber defense efforts through rotational training, NATO exercises, and foreign military sales and support.

Coastal Defense (CD)

The Ukrainian Army, not the Navy, should develop and operate Coastal Defense Cruise Missile (CDCM) battalions. The Army has deeper funding and manning levels to be able to better integrate this additional mission. Other nations employ this model. Namely, the Japan Ground Self Defense Force is responsible for operating/employing CDCMs against enemy ships. Giving the coastal defense mission to the Army will lessen the burden on the Navy and allow it focus on sea denial operations while the Army supports these efforts from the littorals. Command and control between Army and Navy units is paramount to ensure target coordination. Modern C4ISR networks should aid target cueing. The Army can organize mobile battalions to employ shoot-and-scoot tactics from concealed positions against the enemy fleet at sea. If the new Neptune ASCM passes operational testing and evaluation, Ukraine can mass-produce these ASCMs to achieve economy of scale and equip Army CDCM battalions. Ukraine has a naval infantry arm which could also take on the coastal defense mission. However, the Army should operate the CDCMs over the naval infantry because the latter is a mobile strike fighting force, while the Army has broader experience and funding support for artillery and related mission areas.

Helicopter-Based ASUW Capability

Helicopters should possess an air-to-surface anti-ship missile capability to complement the surface fleet and coastal defense ASCM capabilities. This strategy completes the triad of anti-ship missile forces operating from land, air, and sea. Helicopters can operate from unprepared airfields, an advantage over fixed-wing aircraft which require a longer, prepared runway. Helicopters can hover at low altitudes for longer periods of time – a suitable platform for conducting ASUW from the air. Ukraine should attempt to fit the indigenous Neptune missile on helicopters to field a formidable anti-ship platform in the SOA littoral.

Mine Warfare (MIW)

Ukraine should develop a defensive mine warfare capability to protect the Ukrainian coastline as well as to have the ability to conduct chokepoint denial operations. Bottom, moored, and influence mines should be adapted to the shallow operating environment of the SOA. In addition, the Ukrainian Navy should invest in mine-clearing capabilities to counter potential Russian mining of SOA and the Kerch Strait. An unmanned mine-clearing capability is likely more economical than sweepers with a crew of 30 personnel. NATO countries should help Ukraine obtain an affordable mine-clearing capability. Such a defense-oriented system would not threaten Russia. Furthermore, providing this level of support does not cross the threshold that would require a NATO membership for Ukraine.

Pay, Housing, and Training

Finally, improvements in the morale intangibles are indispensable for building a modern navy. Ukraine must increase military wages and expand access to housing which cuts to the root of persistent low morale. Only then can Ukraine begin to turn the tide on poor job performance, recruiting, retention, and even defections. A robust training program is also necessary to be effective in asymmetric warfare. Old ammunition stockpiles should be renewed for safe training and operations. Above all, training should emphasize the Ukrainian joint force ability to defend the SOA with no help from other countries, in line with geopolitical realities. In addition, exercises with NATO provide invaluable interoperability and high quality training opportunities, and thus should be continued.

Joint Sea Denial Strategy

Ukraine should animate the above fleet investments with a cohesive joint doctrine to conduct sea denial operations. The goal of sea denial is to prevent sea control, and therefore, preventing Russia from using the sea to do harm through amphibious landings, blockade, and fires against shore defenses.7 Currently, Ukraine has local control only along its coast and cities such as Mariupol and Berdyansk. Patrols and coastal surveillance should ensure that no suspicious vessels operate near the littorals. Russian Special Forces may operate close to the littorals on civilian vessels feigning as fishermen or conducting commercial shipping. Through exercises that focus on interoperability, U.S. and NATO Navies can provide training on maritime interdiction and patrol operations to develop doctrines to help Ukraine defend its borders from the seaborne equivalent of Russia’s little green men.

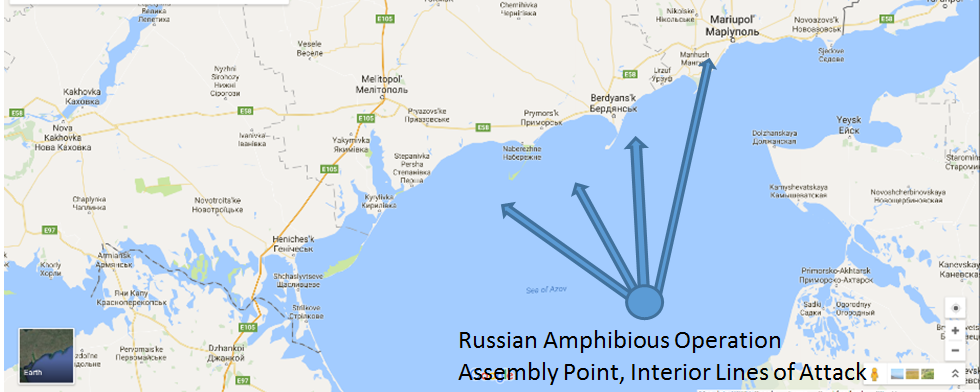

In wartime, Ukrainian forces should focus their attack on the Russian Special Forces, ground, and amphibious forces on military or commercial transports. Thus, the primary focus of effort for Ukrainian surface combatants, CDCMs, and helicopters should be concentration of fires on transports carrying Russian troops and Special Forces to deny seaborne invasion and infiltration. If Russian surface combatants are protecting the transports, Ukraine must threaten those combatants to strip away protection. The secondary target is to weaken enemy sustainment by attacking supply ships and commercial vessels carrying materiel. Tertiary targets should be enemy operational fires capabilities, i.e., ships with naval gun fire support, Russian air support, and artillery. Ukraine forces should jam enemy communications to prevent effective C2 and weaken enemy intelligence gathering efforts through operational deception.

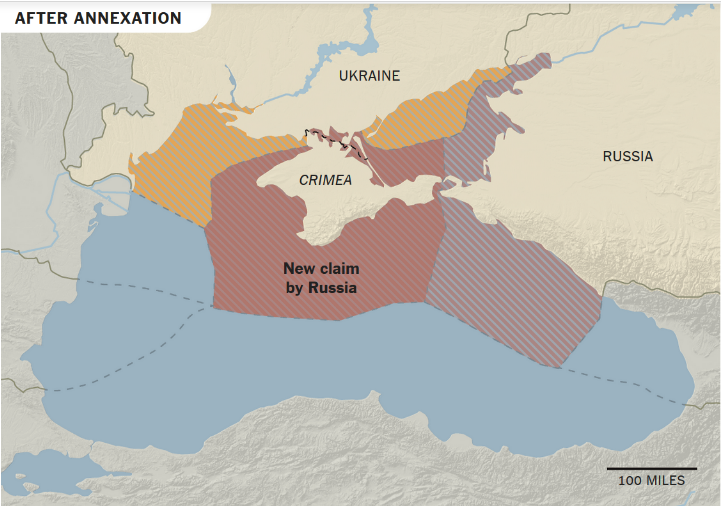

Ukraine Chokepoint Denial Operations

Eventually in wartime, Ukraine must try to deny Russia’s ability to control the Kerch Strait through chokepoint denial operations. The Ukrainian Navy must use its asymmetric fleet with swarm tactics, surprise, and concentration of force against the Russian fleet when they are most vulnerable coming through the Kerch Strait. This will likely be a large missile engagement; therefore, the side with more firepower that presents the most elusive targets will win. If Ukraine is unsuccessful in preventing Russia from closing the Strait, Russia will be able to control the OPTEMPO in the SOA and isolate eastern Ukraine while threatening vital coastal cities such as Mariupol. Dividing Ukrainian forces will lead to a quick and eventual defeat, resulting in Russian dominance in the SOA. Russia’s commercial interests, sea mineral resources, and Crimea’s rear area will be secure from foreign threats. This is Russia’s desired end state, which Ukraine must prevent through sea denial and choke-point denial operations.

Mariupol Naval Base

The last part of the strategy is to establish a naval base in Mariupol and forward deploy a part of its asymmetric fleet to help defend it. Mariupol is Russia’s ultimate operational objective in a scenario that seeks to connect Crimea and Russia. For Ukraine, Mariupol is its theater-strategic center of gravity in preventing Russia from annexing the Priazovye region. Since the loss of Sevastopol to Russia, the Ukrainian Navy has only one operational base in Odessa. Currently, there are no Navy bases east of the Crimean Peninsula. Therefore, Ukraine should consider establishing a naval base in Mariupol as it is the most favorable city with natural harbors, a sizeable population, and an industrial base to sustain a moderate naval and Sea Guard force. Establishing a naval base in Mariupol will enhance the ability to safeguard maritime rights in SOA during peacetime and conduct sea denial operations during wartime. The Sea Guard also already has a base in Mariupol. Co-location of the Navy and Sea Guard with shared use of repair and logistics facilities would alleviate resource constraints while investing in resilience in the form of resupply points and depots along the Azov coast and inlets to support replenishment. An over-reliance on Mariupol creates a singular vulnerability to attack, as seen in separatists’ offensives against Mariupol in 2014/15. Ukraine must diversify risk by spreading out resupply capabilities throughout the Azov coast.

Finally, Ukraine should station about one-third of the Ukrainian Navy assets in Mariupol. This balance would be favorable to have enough economy of scale and concentration of force to conduct effective patrols and have a deterrent effect against the adversary. Critics may point to the fact that forward-deploying a large percentage of Ukraine’s fleet in the SOA would be akin to trapping the fleet if Russia closes the Kerch Strait. That is the reason why Ukraine should not deploy more than one-third of its fleet to Mariupol. If Russia establishes control of SOA and closes the Kerch Strait, the SOA fleet would be trapped in; however, Ukraine would still possess two-thirds of its fleet in Odessa as an operational reserve for a possible future counterattack. Nevertheless, one-third of the Ukrainian fleet patrolling the SOA is a marked improvement from the current situation, which is a weak, sporadic, or virtually non-existent presence in the SOA. Forward presence would be a step in the right direction to show resolve and stave off potential encroachment of Ukrainian territory.

Counterargument

Why build an asymmetric fleet and position over a third of its force to the frontlines? After all, this action may provoke a Russian reaction. In addition, an ill-conceived asymmetric navy will not deter a determined and capable Russia from further encroaching on Ukrainian territory. Western sanctions and fear of diplomatic reprisals have so far deterred Russia and separatists from taking over Mariupol. Russia will not be able to brook further sanctions on its already fragile economy. Thus, Russia will weigh the risk versus the rewards, and decide that it is not in Russia’s interest to take actions that would further result in crippling sanctions on its economy. Therefore, Ukraine should spend its precious resources elsewhere to help its citizens. Furthermore, any resources spent on the Ukrainian military should continue to prioritize the army and air force which are doing the lion-share of fighting in the Donbas region.

However, sanctions have seldom deterred Russian actions. Russia’s honor, prestige, and the importance of holding Crimea far outweigh the risks of sanctions and how the international community will regard such an action. If Russia cannot resupply Crimea adequately, the fear of potentially losing Crimea will force Russia to take measures to ensure Crimea’s survival by building a land corridor to Russia. Russia will factor the Ukrainian Army’s relative strength over the Ukrainian Navy’s weakness. If Ukraine takes no action to prioritize and strengthen its naval and coastal defense forces, the power vacuum left in the SOA will tempt Russia to regain its former territory via the sea. What would become of the Ukrainian government’s legitimacy when it cannot defend its country again from foreign attacks, including those from the maritime domain? The risks of inaction are greater than they appear.

Conclusion

Following Crimea’s seizure, Ukraine continues to face threats of Russian encroachment on its territory. Russian designs are based on geopolitical needs for resources, consolidation of gains, and resupply of Crimea via a land corridor linking to Russia. Supported by historical narratives of “Novorossiya,”8 Russia will time the invasion by hybrid forces when Ukraine is weak and the international community’s attention divided. As in the case of Crimea, seizure of the Azov coast will be swift, probably led by “little green men” using plausible deniability and supported by separatist forces from Donbas region.

Ukraine has three main ways to counter future Russian aggression in the SOA: develop an asymmetric force, conduct joint sea denial operations, and forward deploy forces to defend Mariupol. Ukraine must implement this strategy immediately. The risk of inaction is too great for Ukrainian territorial sovereignty. In the end, Russia’s overwhelming military power may be too much for a small, underfunded Ukrainian military. The idea, though, is to introduce enough risk to deter Russia from further aggression against Ukraine. The answer lies with the Ukrainian people which strategy they should pursue.

LCDR Jason Yuki Osuga is a graduate of Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) Europe Center and the U.S. Naval War College. This essay was written for the Joint Military Operations course at NWC.

These views are presented in a personal capacity and do not necessarily reflect the views of any government agency.

References

1. Fariborz Haghshenass, “Iran’s Doctrine of Asymmetric Naval Warfare.” Washington Institute, December 21, 2006. Accessed October 1, 2016, http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/irans-doctrine-of-asymmetric-naval-warfare.

2. Ibid.

3. “CCD Contracts and Technical Briefs,” NAVSEA Combatant Craft Division, August 15, 2015, 30.

4. “Ukraine Develops New ‘Neptune’ Anti-Ship Missile Complex,” Info-News. May 17, 2016. Accessed October 9, 2016. http://info-news.eu/ukraine-develops-new-neptune-anti-ship-missile-complexe/.

5. Eugene Garden, “Ukraine Plans for 20 New Patrol Boats,” Shephard Media, March 8, 2016. Accessed October 9, 2016. https://www.shephardmedia.com/news/imps-news/ukraine-plans-20-new-patrol-boats/.

6. “Ukraine Develops New ‘Neptune’ Anti-Ship Missile Complex,” Info-News.

7. Geoffrey Till, Seapower: A Guide for the 21st Century, (New York: Routledge, 2013), 152.

9. Kirill Mikhailov, “5 Facts About “Novorossiya” You Won’t Learn in a Russian History Class,” Euromaidan Press, October 17, 2014. Accessed 01 Oct 2016, http://euromaidanpress.com/2014/10/17/5-facts-about-novorossiya-you-wont-learn-in-a-russian-history-class/#arvlbdata.

Featured Image: Gurza-M (Project 58155) small boat of the Ukrainian Navy. (Ministry of Defense of Ukraine)

influence of emerging naval platforms and technologies in the geostrategic contours of the Indo-Pacific region. It identifies relevant historical precedents, forming the basis for various maritime development and security related projects in the region.

influence of emerging naval platforms and technologies in the geostrategic contours of the Indo-Pacific region. It identifies relevant historical precedents, forming the basis for various maritime development and security related projects in the region.