By Todd M. Hiller, P.E.

“. . . without their skill and devotion to duty our men and materiel could not have been delivered. . . “–President Franklin D. Roosevelt

The U.S. flag commercial fleet and government owned vessels serve a crucial capability to successfully execute and accomplish USTRANSCOM’s (USTC) worldwide operations by sea. Ongoing issues occurring in the global commons have pressured USTC reliance on the U.S. Merchant Marine through the Military Sealift Command (MSC) and the Maritime Administration’s (MARAD) Ready Reserve Force (RRF).1

Enduring commitment to historic naval functions of deterrence, sea control, power projection and maritime security remains essential to American national strategy; however, the security conditions have become more sophisticated and uncertain, forcing the Department of Defense to change how it conducts sustainment operations. Through a distinguished history of sacrifice, valor and courage, the U.S. Merchant Marine has proven its tenacity in support of a common calling to serve the nation.

Today, threats continue to compel the United States’ need for strategic sealift. Considering the nation’s dependency on imported products, it is timely to reconsider just how dependent the international supply chain is on the primary conveyance for cargoes coming to and from the United States. Over 90 percent by volume or weight comes by sea, but American flagged carriers account for less than 2 percent of these cargoes. American dependency on foreign-flag vessels will inevitably become more problematic with the continuation of stop-gap measures to meet national security requirements.

With a bi-polar hegemonic world, the U.S. needs to take an immediate and serious deep dive into guaranteeing commercial cargoes for U.S.-flag carriers. This is not a new idea, but one worth revisiting. This proposal, if enforced by treaty or legislation, would have negligible impact on shippers while significantly improving the capacity and number of both the U.S.-flag fleet and U.S.-mariners.

Domestic Shipbuilding Capacity

The United States’ sealift fleet has received limited Congressional attention over decades of continued use. New construction and conversion of Maritime Prepositioning Ships and the development of large medium speed roll-on/roll-off vessels achieved successful results, but the alignment of sealift ships under a 30-year shipbuilding plan has never materialized. Most recently, the Navy’s 30- year shipbuilding plan and the SECNAV’s Sealift that the Nation Needs (STNN) report to Congress (2018) considered sealift vessels or auxiliary vessels.

However, its vessel proposals are not in sufficient numbers and the timeline described to achieve increased readiness and availability is not effective. Sealift vessels generally fall into 10-15 year shipbuilding periods, with long lapses between programs that can exceed 10 or even 20-years. These aging vessels are often managed with decreasing levels of resourcing over time, despite the increasing need. The greatest shortfall in plans for a viable sealift fleet involves short-term programs of 20-25 years or less, for a fleet intended to last 50 or even 60-years.

The sealift fleet includes both commercially-operated vessels, in-service, as well as organic sealift vessels, many of which were former commercial vessels or built to rigorous commercial classification society standards. Both the United States government and the shipbuilding industry would benefit from a shipbuilding plan that identifies ship construction opportunities over a 20–30-year timeframe.

- The Navy’s existing Long-range (30-year) Shipbuilding Plan narrowly focuses on Combatant and Auxiliary vessels; leaving sealift vessels for ad-hoc recapitalization strategies.

Acquisition and modernization of ships for defense agencies has been successfully executed since 1976. Capital improvements were executed through the modernization of Joint Logistics over the Shore (JLOTS), Offshore Petroleum Discharge System (OPDS), and an intentional shift from breakbulk cargo to roll-on/roll-off vessels. Staying current with modern technology, MARAD was forced to continually upgrade the organic fleet to deliver increased sealift capacity to meet the demand signal from USTC. Today, the STNN report outlines a path that provides limited resourcing of ships on a progressive, but low-accession rate. Newer ships, ships built today and those available for procurement do not match ships built 30-40 years ago in terms of structural arrangement (scantlings) or suitability for laid-up status – both of which are important considerations for strategic sealift.

Shipbuilding Plan

MARAD has proposed development of a long-term, planned sealift shipbuilding initiative that focuses on commercially-developed but militarily useful ships. The greatest gap in shipbuilding is the difficulty in constructing ships usable for commercial purposes that could also be useful as naval auxiliaries in time of war or national emergency. By developing a shipbuilding plan, MARAD seeks to coordinate with commercial ship owners, whereby the government invests a reasonable or an agreed upon portion of the cost at new construction for any vessel, and after operation for a period of ten years commercial service, accepts the vessel into the organic sealift fleet for an additional 20-25 years. By offsetting the initial, up-front costs for ship owners, and including national defense features in construction, MARAD would recapture a stake in the efficient construction and operation of a U.S. flag vessel. Participation would come with conditions including periodic inspection, equipment validation, modernization upgrades, and other program involvement as well as full Voluntary Intermodal Sealift Agreement (VISA)/Maritime Security Program (MSP) enrollment. This initiative works in conjunction with all other sealift programs to ensure a continuing supply of modern, U.S.-built ships for procurement for defense needs.

At scale, this plan could include the construction of four ships per year for ten years, for acceptance by the Government after ten years. The 4/10/20 plan involves initial investment by the Government, paired with industry financing to build U.S. flag ships in domestic shipyards. This accession rate exceeds the rate of the STNN report, decreases the average age of the commercial / organic sealift fleets, and reduces a reliance on foreign-built ships for defense purposes. Most importantly, this plan provides a predictable timeline of ship construction options at a rate of four ships per year. Because the government pays their share up front, concerns of subsidies can be avoided, and it combines both government funding and private financing for greater effect in the shipyard industrial base.

MARAD’s key focus areas for domestic shipbuilding capacity include:

- Continuation and expansion with reduced barriers of application and award of the Title XI financing.

- Development of a sealift plan that parallels Navy’s 30-year Shipbuilding Plan and provides insight to optioned ships (4/10/20 Plan)

- Continued effort to align all non-combatant, national shipbuilding needs through the Government Shipbuilders Council (GSC-V)

- Revision of the National Defense Features and Sealift Enhancement Features catalogues for outfitting on any U.S. flag ship

- Availability of other sealift programs, including procurement for NDRF, Ship Disposal Programs, etc.

Single Sealift Manager

The nation’s sealift capacity exists in multiple organizations with potential shortfalls as these ships age and competition for resources does not match organizational objectives. Through multiple ship repair contracts of existing ships, both the MARAD and Military Sealift Command (MSC) compete for available dry-docks in an increasingly difficult regulatory environment. With ship repair availabilities taking longer, ships and their programs must choose to prioritize based upon the urgency of the ship’s required performance, e.g. prepositioning, and the regulatory requirements of American Bureau of Shipping and the U.S. Coast Guard. Aligning sealift capacity to one single manager could alleviate congestion and give greater insight to shipyards seeking work on up to 61 ships.

Reroute Ad Valorem Tax Funds

Domestic shipyard availability, increasingly longer and more complex repairs, and skilled worker shortfalls means that repairs in foreign shipyards may be more desirable or simply necessary due to availability and skilled labor pools that combine to meet an approved ship repair availability timeline. Today, MSC ships and even MARAD’s RRF ships still face 50% Ad Valorem taxes for repairs made overseas.2 The benefit of this tax is not gained by the industry, as the intent of the tax is meant, because it reverts only to the Department of the Treasury. Moving into a period of necessary ship construction revitalization, MARAD has proposed that the Ad Valorem tax be revised to fund activities that directly benefit domestic shipyards, through funds applied for increased infrastructure improvements, cybersecurity and industrial security, sill dredging, and skilled worker recruitment and training. By applying Ad Valorem funds directly, this initiative could be executed like the Small Shipyard Grant Program, through a validation process recorded and assessed by MARAD.

MARAD’s key focus areas for redirecting Ad Valorem funds to domestic shipyards include:

- Select infrastructure improvements and modernization

- Cybersecurity and industrial security measures

- “Last mile” graving dock and floating dry-dock area sill dredging

- Skilled worker recruitment, training, and apprenticeship programs

There are many factors to take into consideration in the rapid decline of the shipbuilding industry, including global oversupply, recessions and changing economic fundamentals, but one policy decision clearly stands out. For decades, countries around the world have subsidized their national shipbuilding industries. Up until 1981, the U.S. followed suite through the payments of construction differential subsides (CDS). As soon as foreign shipbuilding companies gained the advantage of subsidization from their governments, subsidization for U.S. shipbuilding went in the opposite direction leaving the U.S. industries at a disadvantage and unable to compete for business.

Currently, the U.S. ranks 19th in the world for commercial shipbuilding, accounting for approximately 0.35% of global new construction, which is a mere one-third of one percent of new commercial shipbuilding occurs in the United States, despite having the world’s largest economy.3 In the absence of any U.S government action to enforce fair market participation, the commercial shipbuilding industry almost immediately began to suffer a steady decline and struggled to remain competitive against foreign subsidization. The impact of these trends is evidently clear. South Korea has 37% of global shipbuilding, Japan has 27% and China has 21%.4 South Korea alone is building more than 100 times the number of ships as the United States.

Maritime Security Program

Military, congressional, and other government leaders noted that while MARAD’s RRF offered an effective and rapid source of ships for strategic deployment, even the RRF and the sealift capabilities of Military Sealift Command together could not sustain a serious and prolonged U.S. military deployment overseas. Additional support from a commercial U.S.-flag merchant marine is essential for strategic sealift requirements, as was proven in all American wars of the twentieth century, including Operations DESERT SHIELD and DESERT STORM. Accordingly, in 1996, Congress passed and the president signed the Maritime Security Act of 1996 (MSA), which established the Maritime Security Program (MSP).

The Maritime Security Program (MSP) maintains a fleet of 60 modern, privately-owned U.S.-flag ships, active in international commercial trade, yet available on-call to meet U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) contingency requirements during war and national emergencies. The MSP ensures a minimal but vital role for the U.S. in global sea trade, while employing some 2,400 of the trained, skilled U.S.-citizen Merchant Mariners needed to man the Government-owned surge fleet in times of crisis.

The current MSP fleet includes 23 container ships, 11 geared container ships, 18 roll-on/roll-off (RO/RO) vessels, six multi-purpose/heavy-lift ships, and two tankers. The cargo capacity of the MSP fleet, now exceeding 3.4 million sq. ft., is at the highest level in the program’s history, including some 117,000 TEUs, 3.16M sq.ft. of RO/RO capacity, 335,659 sq.ft. of heavy-lift capacity, and nearly 667,000 bbl. of fuel transport capacity.

Cargo Preference

Cargo preference statutes are crucial to U.S.-flag vessels and American commercial sealift. Currently, DoD cargoes are contracted through USTC, either by Surface Deployment & Distribution Command (SDDC) or MSC for full ship charters. However, a large portion of other government cargoes are shipped by various other agencies. Centralizing the contracting of all government impelled cargoes under USTC could effectively and efficiently reduce cost, increase visibility, increase cargo preference adherence, and strengthen national strategic sealift capability. USTC has the robust transportation in place to support this centralization.5

Sealift Recapitalization

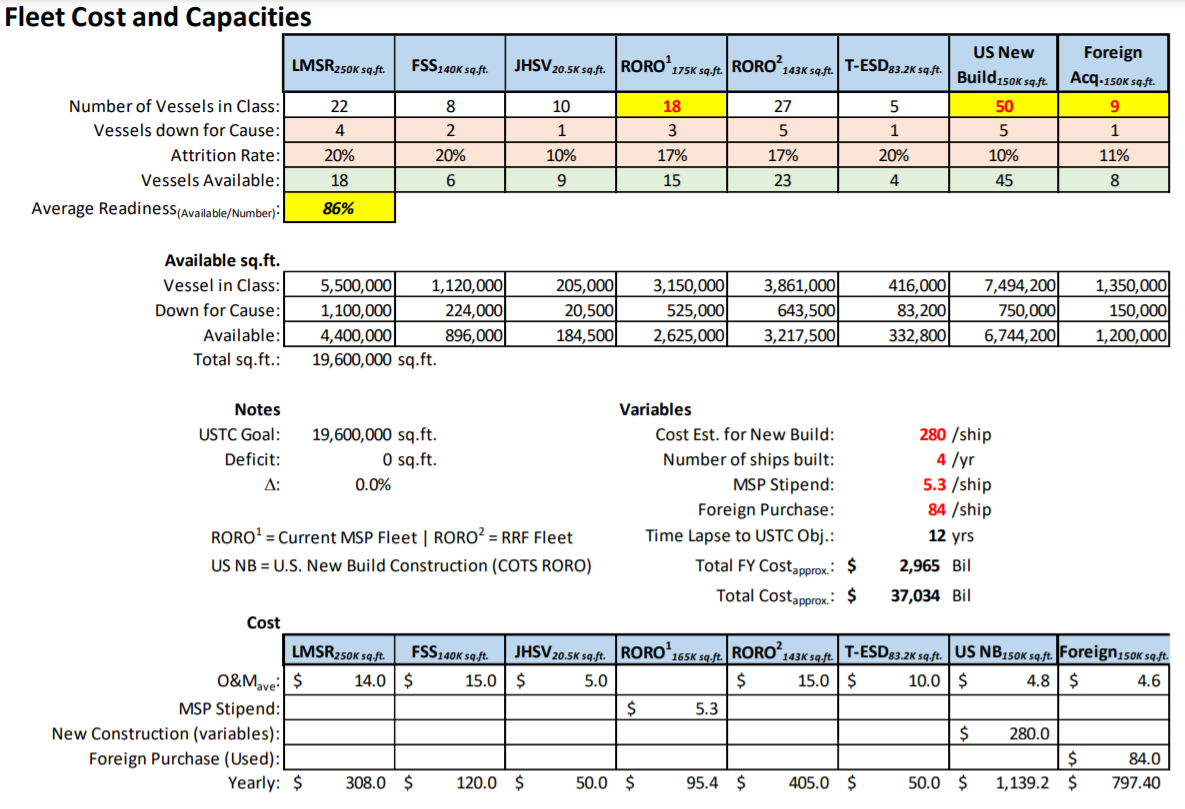

In an effort to increase the RO/RO capacity through the MSP, scenario comparisons were made to show a generic time line and cost to reach USTC requirement for sealift square footage. To start, data of the notional Army unit types was used to calculate the number of vessels of each class to carry a full complement, Table 1.

Next, three scenarios were created, with assumed variables, how much it would cost and how long it would take to bring American strategic sealift within mission readiness standards set by USTC.

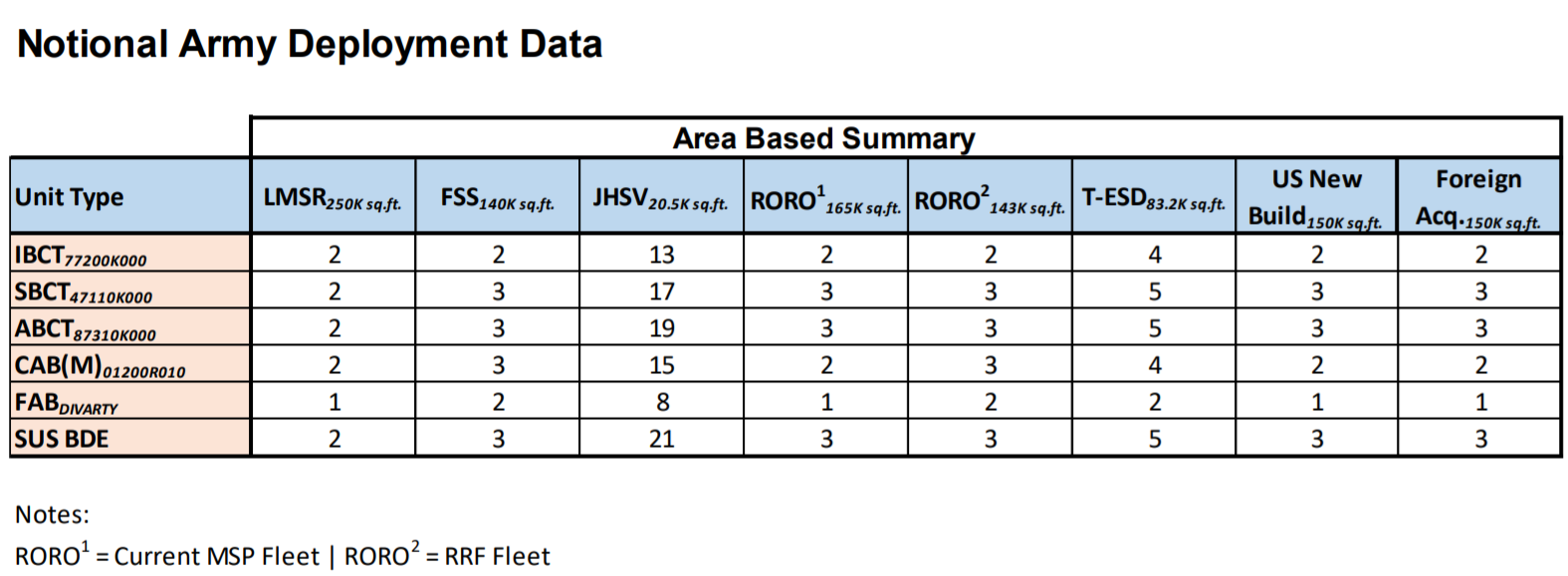

Scenario #1: Emphasis on a new construction program with new Commercial off the Shelf (COTS) RO/RO vessels replacing Large Medium Speed RO/RO (LMSR)’s currently in the afloat prepositioning fleet, and shifting to surge. Estimated time to meet USTC mission readiness is 12 years.

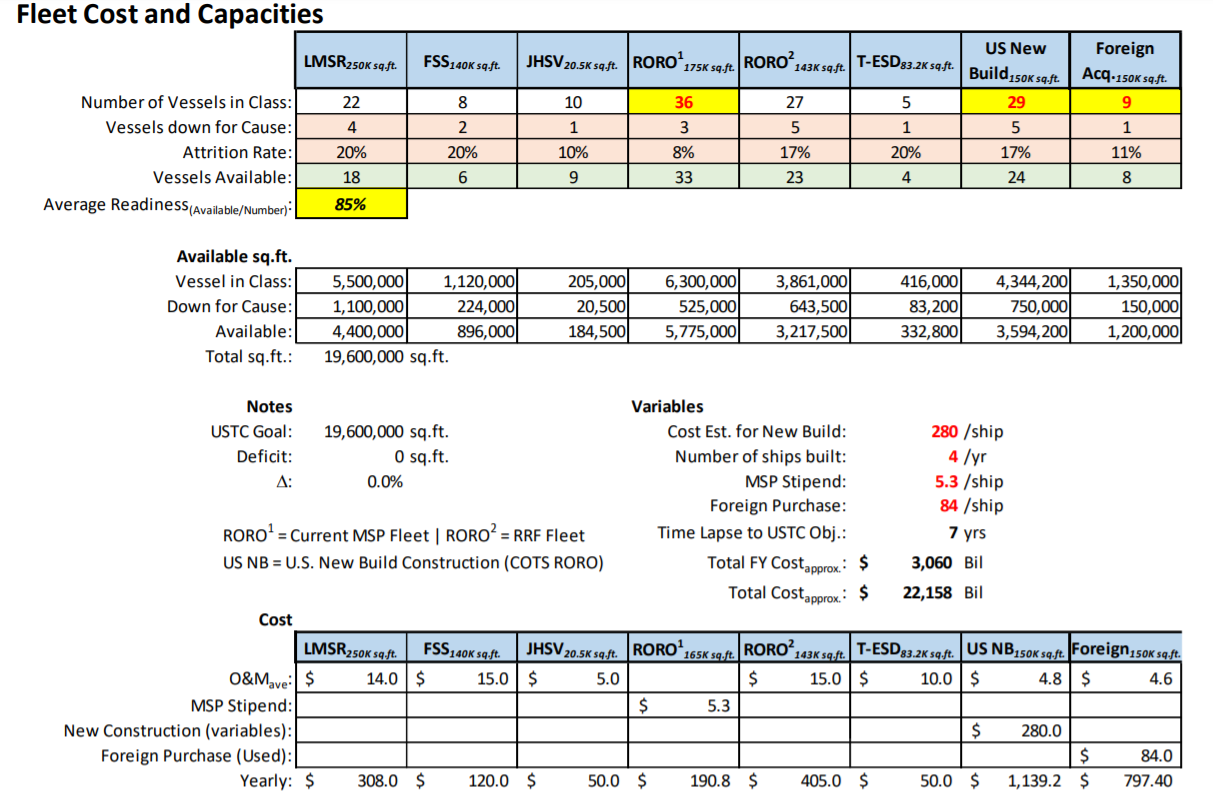

Scenario #2: Double the commercial MSP fleet of RO/RO vessels and limiting the number of new COTS RO/RO vessels to analyze the commercial increase option. Fewer new vessels will be constructed leaving funding for purchasing used commercial RO/RO’s in the open market. Estimated time to meet USTC mission readiness is 7 years.

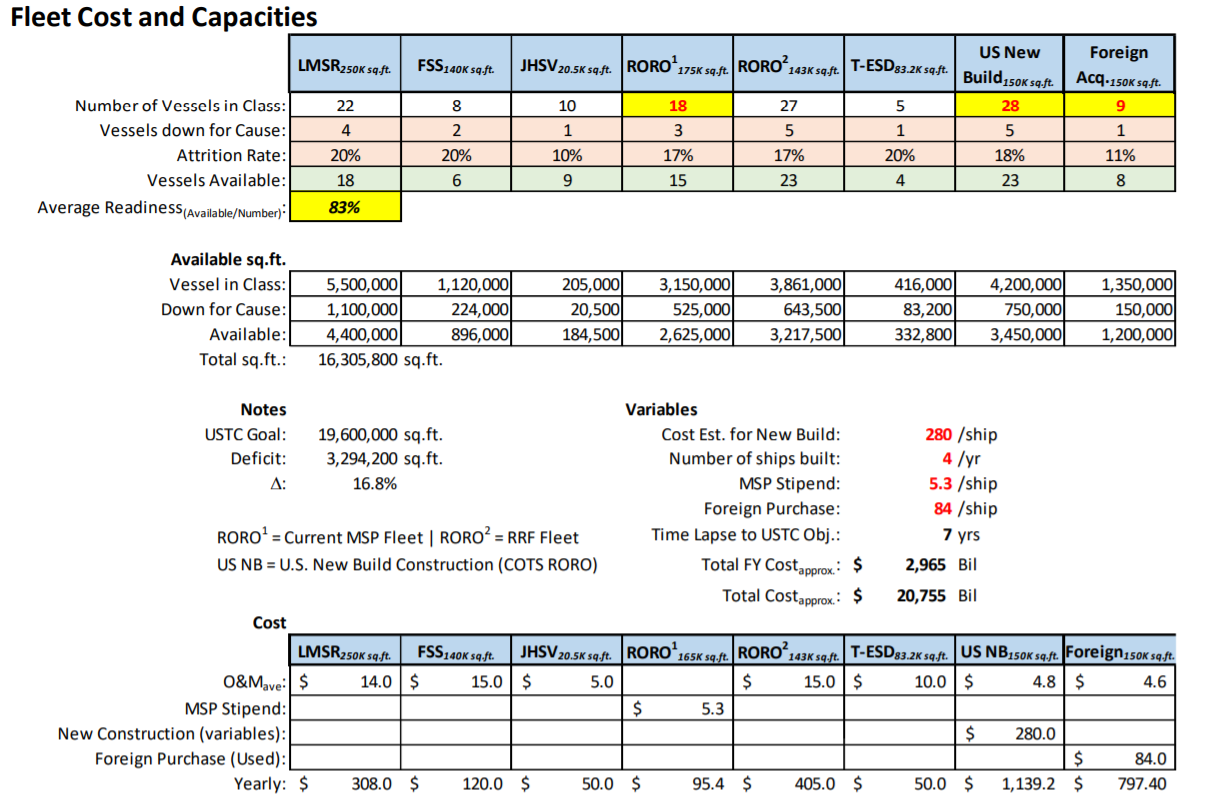

Scenario #3: Same as Scenario #1 with the exception of restricting the time limit met in Scenario #2 of 7 years. This scenario fails the square footage requirement to meet USTC mission readiness.

Table 1 – Notional Army Deployment Data

Scenario 1: 18 MSP RO/RO Vessels w/ 50 New Build & 9 Used Foreign (12-year period)

(Click to expand)

Scenario 1 Summary

Case maintains a status quo of 18 MSP RO/RO vessels in the fleet with 50 U.S. new construction incorporating commercial build specifications with national defense features and complying with the Jones Act. The time to meet the TRANSCOM requirement of 19.6 million sq.ft. is 12 years at $3.0B per year for a total cost of $37.0B. Factors in the estimate include an average attrition of 17% for shipyard availability, general repairs and maintenance. Average cost for a new U.S. built COTS vessel is estimated at $280M per ship with 4 new vessels planned per year. Purchasing used foreign RO/RO’s is estimated at $84M per ship with approval to purchase up to 9 off the open global market. Estimates do not include rate of which ships are removed from service and either scrapped or placed into the NDRF.

Scenario 2: 36 MSP RO/RO Vessels w/ 29 New Build & 9 Used Foreign (7-year period)

Scenario 2 Summary

Case doubles the MSP RO/RO fleet to 36 vessels in the fleet with 29 U.S. new construction incorporating commercial build specifications with national defense features and complying with the Jones Act. The time to meet the TRANSCOM requirement of 19.6 million sq.ft. is 7 years at $3.0B per year for a total cost of $22.2B. Factors in the estimate include average attrition of 17% for shipyard availability, general repairs and maintenance. Average cost for a new U.S. built COTS vessel is estimated at $280M per ship with 4 new vessels planned per year. Purchasing used foreign RO/RO’s is estimated at $84M per ship with approval to purchase up to 9 off the open global market. Estimates do not include rate of which ships are removed from service and either scrapped or placed into the NDRF.

*** Notable savings with Scenario #2. Fleet restored to 85% mission readiness, which includes a 17% attrition, 40% of the time and 41% savings. ***

Scenario 3: 18 MSP RO/RO Vessels w/ 28 New Build & 9 Used Foreign (7-year period)

Scenario 3 Summary

Case maintains a status quo of 18 MSP RO/RO vessels in the fleet with 28 U.S. new construction incorporating commercial build specifications with national defense features and complying with the Jones Act. This scenario fails to meet the TRANSCOM requirement of 19.6 million sq.ft. at the 7-year mark with a delta of 16.8%. With 17% attrition for shipyard availability, general repairs and maintenance, mission readiness fails to meet at 83%. All variables and assumptions were the same applied to Scenario 1 and 2.

Potentially increasing the MSP fleet size, MARAD’s selection criteria for new ships entering the current MSP fleet reflect DoD’s stated priority preferences by vessel type. With the priority emphasized on RO/RO’s, replacements are already under an MSP Operating Agreement tend to be the same types as those being replaced. Two key benefits of increasing the MSP RO/RO fleet, they are instantly mission capable and operationally ready for service.

There are inherit risks to increasing the MSP. Some of these capabilities can never be fully replaced without construction or modifications. However, vessels of the U.S. flag commercial fleet can be purchased and modified to replace some Ready Reserve Force/MSC assets, as provided for in the U.S. Navy’s current surge fleet recapitalization planning. For political or economic reasons, the U.S. military could find itself in a situation in which foreign-flag shipping is not an option to support U.S. military operations.

For instance, due to prior circumstances of particular conflicts, flag states may refuse to permit their vessels to enter a war zone so as not to offend an ally or related business interest or operators do not wish to charter vessels to the U.S. military because they could potentially lose market share from their regular, existing customer base and trade routes. From a foreign operator’s perspective, carrying U.S. military cargoes, even at premium rates, may be a poor business decision in the long term, which may discourage foreign-flag owners and operators from even considering such an option.

New Cargo to Maintain the Commercial Sealift Fleet

In the 1970s the United States negotiated a bilateral agreement with Brazil reserving 40% of each country’s exports for the merchant fleet of each trading partner and the remaining 20% was available for third country fleets. Shortly thereafter the United States negotiated a similar bilateral agreement with Argentina. These agreements gained the interest of many developing nations and thus the “40/40/20” became a new standard adopted by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) Code of Conduct for Liner Conferences. The UNCTAD Code came into force on October 6, 1983, six months after its ratification. However, the United States never ratified the Code even though the U.S.-carriers and the U.S.-maritime unions were supportive. The UNCTAD 40/40/20 was designed around the ocean shipping conferences that dominated ocean liner trade in the 1970s. Subsequently over the following decades, due to changing political environments, conferences have become unlawful in some parts of the world and are now practically non-existent. However, during this same period, carriers have developed operational conferences or cooperation in the form of vessel sharing agreements (VSAs), also referred to as liner consortia.6

Strategic Sealift Officers

Strategic sealift is essential to the U.S. Navy’s ability to carry out its sea control, power projection, and maritime security missions—and essential to strategic sealift is a cadre of Navy Reserve officers who provide emergency crewing and shore-side support for the Military Sealift Command’s Surge Sealift Fleet and the Ready Reserve Force in times of national defense or emergency.

Strategic sealift officers (SSOs) today have two priority missions: to provide strategic depth as tactically trained, experienced, and credentialed licensed mariners; and to deploy operational capability through their subject matter expertise in marine engineering, operations, and logistics and ties with the maritime ecosystem.

This diverse maritime expertise is a force multiplier. The broad educational backgrounds, world- wide employment and specialties in work experience enable these dedicated mariners to apply critical skills and non-traditional methods to overcome current and future obstacles. Members will use their unique maritime industry understanding, training, and proficiencies in support of U.S. Navy and national-level requirements.

Years of specialized training and education are required to earn and maintain the U.S. Coast Guard Merchant Marine license and associated additional credentialing by the International Maritime Organization (IMO). The U.S. Merchant Marine must continue to attract, retain, and promote top talent from the nation’s maritime academies. This workforce is the key enabler to accomplish a vital mission.

Concepts of Maritime Solutions

Strengthen the Maritime Industrial and Innovation Base. Reinvigorate and promote a competitive modern maritime industrial and innovation base. Leverage commercial leading-edge suppliers to provide a strong and sustained competitive advantage within the global maritime commons.

Sustain the Forces. The Maritime Services should generate resilient and adaptable logistics to sustain forces globally in contested environments. Successful mission execution demands the planning, prioritization and modernization of U.S. flag strategic sealift capabilities, maritime prepositioning network forces, prepositioned forward munition stocks, warfighter provisioning, allied and coalition partner support coupled with distributed and agile logistics. Logistics investments needed include the Next Generation Logistics Ship – which could be a commercial-of-the-shelf (COTS) RO/RO vessel with NDRF capabilities, utilized to sustain afloat and ashore littoral forces and strategic sealift assets within the Ready Reserve Fleet – the Maritime Security Program, and a Tanker Security Program.

Develop Integrated Maritime Forces with fiscal resources allocated to the U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard and Merchant Marine by the U.S. Congress. Consistent and sufficient funding will support the strong maritime defense industrial base needed to deliver future naval and strategic sealift ships, aircraft, munitions and supplies. Steady resourcing will allow the Maritime Services to invest efficiently, provide accountability, preserve military advantages and enable consistent strategy execution in contested environments.

Address the Strategic Sealift Gap and Restore the U.S. Merchant Marine. Both a robust maritime industry and the policies that aim to support it are increasingly important in an era of great power competition (GPC). DoD mobilization requirements depend heavily on the U.S. flag commercial maritime industry. However, with now fewer than 90 vessels, this industry continues to face mounting pressures ranging from fragmented and ineffective policies to highly subsidized foreign maritime assets that undermine its long-term viability, its ability to innovate, and its capacity to support future military operations. To effectively compete, the U.S. must break with a long-standing approach that assumes the commercial and military requirements of the maritime industry are the largely distinct. Instead, the U.S. must adopt an integrated approach that recognizes the inherent interdependence between the two and foster a healthier commercial maritime industry that can effectively support DoD force mobilizations. In just one example, American shipyards require modernization through capital improvements, infusion of more efficient processes and a skilled workforce to fully realize increased capacity and capability. To address this, the development of a long-term, planned shipbuilding and repair initiative that focuses on commercially-developed, but militarily useful ships would inevitability help close the gap in shipbuilding. Without a “leveling” of the playing field for commercial shipyards through some form of construction subsidy, tax incentives, or long- term government shipbuilding program, U.S. shipyards will be unable to construct large commercial vessels at a cost more competitive with heavily-subsidized foreign (primarily Asian) shipyards.

This plan would provide insight and predictability to shipbuilders and an opportunity to construct ships for U.S. flag carriers. MARAD would provide stability where boom-and-bust cycles of episodic sealift shipbuilding has been the norm by supporting a shipbuilding plan in coordination with commercial ship owners, whereby the government invests a significant portion of the cost at new construction for any vessel and after operation for a period of ten years commercial service, accepts the vessel into the organic sealift fleet for an additional 20-25 years.

By offsetting initial, up-front costs for ship owners and by including National Defense features in the construction, MARAD would reclaim stake in the efficient construction and operation of U.S. flag sealift vessels. Participation could come with conditions, including periodic inspections, equipment validation, modernization upgrades and other program involvement as well as full MSP/VISA enrollment. While not excluding Jones Act ships, this initiative would work in conjunction with all other sealift programs to ensure a continuing supply of modern, U.S. built ships in support of an effective military mobilization.

Conclusion

The United States is already emerging from a period of strategic atrophy. American competitive military advantage is rapidly waning. With increased global disorder characterized by the decline in international order, the global security environment is becoming far more complex and volatile than any of us have experienced in recent memory.7 The time is now to recognize and commit to a new and comprehensive National Maritime/Defense Strategy to rebuild America’s merchant marine.

The commercial U.S. shipbuilding and repair industry today exists solely on work provided by government contracts and Jones Act construction and repair work. Absent the Jones Act, virtually all remaining large shipyards would be forced out of business, with a negative ripple effect on the supporting supply chain. U.S. shipyards need some combination of subsidies, stimulus, and predictable demand to compete with foreign shipyards that enjoy all of those advantages. American yards require modernization through capital improvements, infusion of more efficient processes, and a skilled workforce to fully realize increased capacity and capability. Those investments are not likely without external assistance.

Ways of promoting the U.S. Merchant Marine and substantially increasing the number of U.S.-flag ships in international trade are available. First, negotiate bilateral agreements with the major United States trading partners like the Brazilian bilateral agreement of the 1970s construct. The agreements may be constructed around the new Vessel Sharing Agreements and with higher levels of third country participation. Bilateral agreements may be prioritized with other countries based on data as a trading partner with the United States. As opposed to 40/40/20 the agreements could be more reasonably negotiated as 10/10/80 agreements. This should increase U.S.-flag participation in U.S.-trade twofold from the current 2% to 4% and beyond in support of American national security and economic prosperity.8 Second, provide additional tax incentives to U.S. carriers, perhaps along with shipper tax incentives. Existing laws and regulations that discourage operators from flagging their ships in the United States could be revised. None of these efforts would require additional appropriations. As far as tax incentives are concerned, the U.S. Treasury is not currently benefiting from foreign-flag operators paying taxes, so having similar tax breaks for a larger number of U.S.-flag operators would have no significant impact on tax revenues.9 First and foremost, the United States should focus on meeting the requirement for strategic sealift capacity.

Leveraging the commercial employment of SSO members the Navy will strengthen strategic relationships with the maritime industry. Industry partners provide complementary capabilities, unique perspectives and information that improves collective understanding of the operating environment and expands options. Correspondingly, strategic sealift officer experiences within the maritime ecosystem enable rapid identification and development opportunities to apply commercial best practices to more efficiently use resources and optimize operations. Mutually beneficial partnerships within the maritime ecosystem are crucial to national strategy. By being an integral part of the maritime ecosystem and the Navy, the SSO force supports successful naval operations and helps strengthen the preeminence of America as a maritime nation.

The Merchant Marine through Strategic Sealift provides the Nation’s “fourth arm of defense” and has historically organized, trained, and equipped to perform three essential functions: sea control, power projection, and maritime security. Curiously, it was an American, Alfred T. Mahan, who dramatically energized global powers, including, eventually, the United States, about the critical importance of commercial flag-state merchant shipping and accompanying naval power.

Contrary to the term that “size matters”, sealift forces do not need another fleet of 250,000 square-foot capacity LMSR’s. They do need ships that are commercially viable for Jones Act and international trade and that have national defense capabilities incorporated in the early stages of construction and built to commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) specifications. Naval warship design technology is not applicable with strategic sealift vessels. Stick to the basics with the USTC 24-10 specification Appendix A for strategic sealift, not what the Navy assumes it needs for strategic sealift. Coincidently, RO/RO’s are built with similar USTC 24-10 specifications incorporated into the construction with ample deck strength on the permanent decks and clear overhead heights complying with basic sealift requirements.

U.S. strategic sealift needs to be both commercially and military viable, to serve dual purposes for the economic and national security interests. The fleet of strategic sealift vessels will serve no purpose sitting pier side in the U.S. waiting for the next conflict to arise. Ships need to be underway, making way and earning money for companies that have employed those vessels and U.S. merchant mariners.

Since World War II, the U.S. fleet has matured and withered to the laws of supply and demand due to the strength of foreign competition. As a nation, the United States have never let the fleet get too small without performing ambitious analyses in recapitalization or through creative means of subsidies and exclusive contracts.10 Through persuasive realignment of U.S. government policy and legislation that incentivizes the U.S. fleet to become globally competitive would be the fundamental basic principles of reviving a viable Strategic Sealift for the United States and allowing USTRANSCOM to successfully execute and accomplish worldwide operations that strengthen national security and directly contribute to achieving the nation’s objectives.

Captain Hiller is the officer in charge of the Naval Cooperation and Guidance of Shipping (NCAGS) for USCOMNAVCENT and USFIFTHFLEET in Bahrain. In his civilian capacity he works for the Maritime Administration as a naval architect in the Office of Shipyards and Marine Engineering. He holds a bachelor of engineering in naval architecture, U.S. Coast Guard Unlimited Tonnage License, and U.S. Navy commission from the State University of New York at Ft. Schuyler Maritime College and a master’s in national security and strategic studies from the Naval War College.

Endnotes

1. USTRANSCOM Nation Maritime Day Speech, General Paul J. Selva, May 2015.

2. Department of Transportation, Comparison of U.S. and Foreign-Flag Operating Coasts, Sept 2011.

3. Department of Transportation, Maritime Trade and Transportation, 2007, Table 7-2.

4. Ibid.

5. Joint Publication 4-01, The Defense Transportation System, July 2017.

6. Alex Roland, The Way of the Ship, page 328.

7. Letter to the Honorable Mark Esper, Secretary of Defense, Congresswoman Elaine G. Luria, 31JAN20.

8. Revive Merchant Marine, Owen Dougherty, 2017.

9. Back to the Future, Christopher McMahon, 2019.

10. William Geroux, Mathew’s Men Seven Brothers and the War against Hitler’s U-Boats, Penguin Books, 2016.

Feature Image: PACIFIC OCEAN (Oct. 28, 2019) Henry J. Kaiser-class underway replenishment oiler USNS Yukon (T-AO-202, right, prepares to conduct a consolidated loading with commercial tanker MT Empire State. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Patrick W. Menah Jr./Released)