By Keith “Powder” Patton, CDR, USN

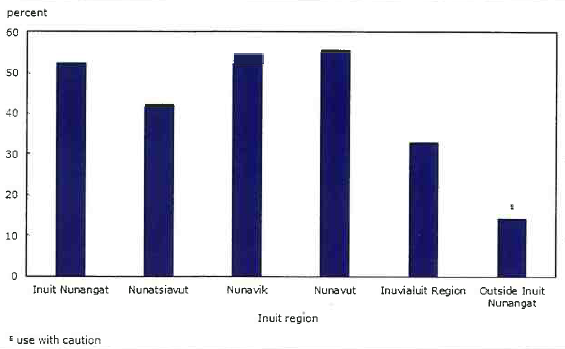

Calculating the power of a fleet is a daunting and imprecise task. In the Washington Naval Treaty, tonnage and gun caliber were used as metrics to set the ratio of capital ships between leading world navies. Capital ships were seen as the supreme arbiters of a naval conflict. The London Naval Treaty established similar rules for tonnage and gun caliber for smaller combatants. The United States Navy counts battle force ships, which includes combat logistics forces, toward its end strength. The battle force ship metric is simple hull count, with T-AKE, PC, LCS, DDG and CVN classes all being counted as equals, despite vastly different mission, size, manning, and capabilities. By a simple measure of hull count from 2018-2019 Jane’s Fighting Ships, the USN has 10 percent fewer warships than Russia, and is half the size of China’s fleet.

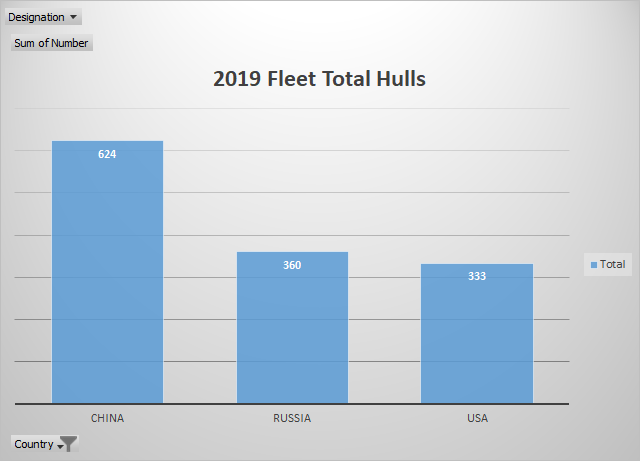

However, when tonnage is used as the metric, the picture changes dramatically:

This change is unsurprising. The nature of the fleets are significantly different. The USN tends to operate much larger ships optimized for long range power projection. China and Russia have many missile-armed patrol boats and corvettes compared to the relatively few U.S. Cyclone class PC and corvette-like LCSs.

However, does the metric of tonnage truly measure the power of a fleet? The interwar period treaties considered both tonnage and caliber of guns. These two metrics were related, in that larger guns required a larger vessel to carry them. In general, there also was a direct correlation between the caliber of the gun and its destructive power. Tonnage also affected how much armor could be carried to protect against gun hits. Another metric used to compare warship power was broadside throw weight. This was the total mass of shells a ship could deliver in a broadside against an adversary. A heavier broadside could be expected to triumph against less armed opponents. However, in the modern era, guns have been eclipsed by missiles as the primary weapon of naval combat. While battleships carried far more powerful weapons and were relatively immune to the deck guns of small combatants, the same is not true of missiles today. Very similar if not identical anti-ship missiles are carried by small patrol combatants and mounted on the largest combatants, sometimes in identical quantities (eight being a popular number). While the defensive and damage control capabilities of larger vessels may be greater, it still seems likely that a few missile hits will knock most ships out of action, if not sink them. If missiles are the true measure of a fleet’s combat power, then neither tonnage nor hull count is an appropriate metric, because neither is directly related to a ship’s missile capabilities.

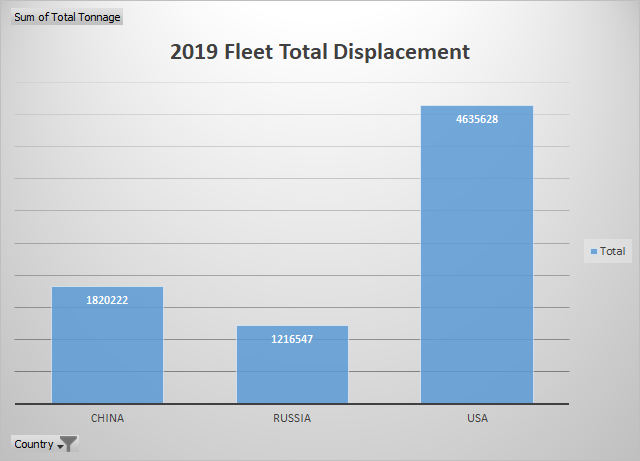

For the sake of this analysis, we will borrow Robert O. Work’s concept of battle force missiles (BFM) from his “To Take and Keep the Lead” monograph. BFMs are missiles that “contribute to battle force missions such as area and local air defense, anti-surface warfare, and anti-submarine warfare. Terminal defense SAMs, which protect only the host ship, are not considered a battle force missile.” Thus, weapons like RAM, ESSM, SA-N-9, Mistral, and HHQ-10 point defense SAMs would not count toward the tally of BFM. ASROC, Harpoon, Tomahawk, Standard Missiles and non-U.S. equivalents do count. Generally speaking, BFMs cannot be reloaded at sea, unlike shorter-range defensive missiles. They are too large and unwieldy. As such, they also serve as a cap on the offensive or defensive power a ship can provide. When BFMs are exhausted, the ship must return to a secure friendly port to rearm.

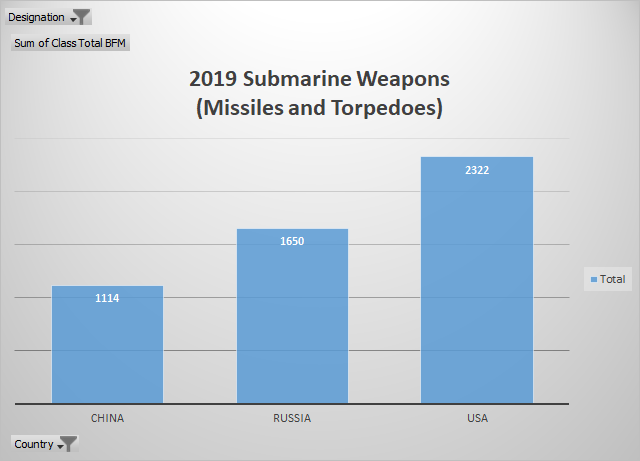

The ship numbers and missile capacity considered below were taken from Jane’s Fighting Ships 2018-2019 as a standard reference. In some cases, there are issues with overlap. For example, some U.S. Mk 41 VLS cells can carry a BFM, or quad-packed ESSM, which would not count. Russian vessels are able to fire SS-N-16 Starfish anti-submarine missiles from their torpedo tubes. While SS-N-16 (like ASROC) would count as a BFM, Jane’s did not have a magazine capacity of how many were carried by Russian warships. So, this BFM-launched via surface ship torpedo tube was ignored. Submarine heavy weight torpedoes were counted. While they may not be missiles, they are a primary anti-surface warfare weapon and, in some subs, are interchangeable with BFMs for strike or anti-ship missions. Finally, there was not complete data for all classes (e.g. number of torpedoes carried), so data was extrapolated from similar designs. The results of this BFM count are in the chart below.

This accounting of fleet firepower shows the USN has more than twice the BFM of the Chinese PLAN. The gap is even larger if the contribution of carrier-born aircraft is considered. The U.S. has an almost twenty-fold advantage in fixed-wing aircraft operating from ships. Carrier-born aircraft, especially from CATOBAR carriers, can carry multiple BFM and can reload aboard the carrier. In addition, the carrier can have its magazines reloaded at sea, something other ships cannot do with their BFMs. However, it is worth noting that China’s BFM count gained over 1000 missiles since 2017, and the U.S. number has been relatively static.

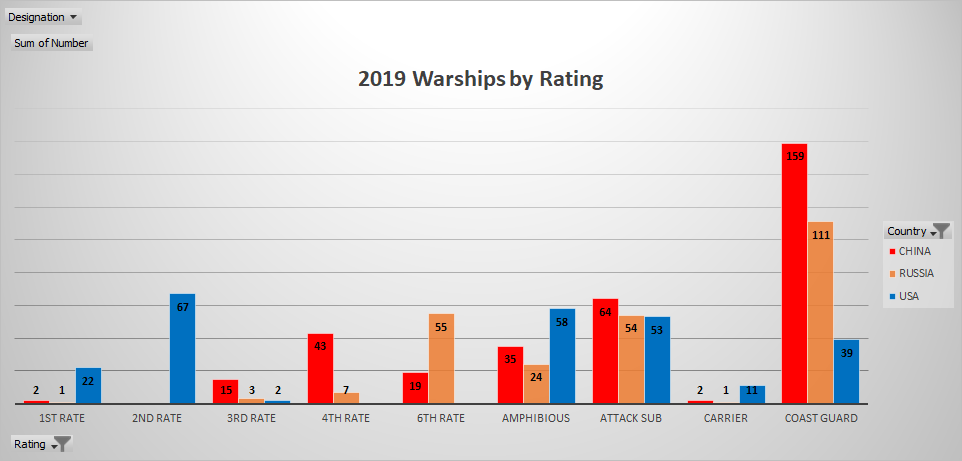

Using BFM as a fleet metric also allows for different ship sizes. A U.S. Flight IIA Burke class DDG with 96 VLS tubes provides the same BFM capacity as 12 patrol boats with 8 missiles each. Who would win in such an engagement would probably hinge on who had better intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) support to target the other first. However, twelve patrol boats also have the advantage of being able to be in multiple places at once and needing at least 12 hits to defeat – far more than the Burke could likely endure. Continuing with Robert Work’s characterization, we can classify ships by their BFM count. Currently, warships have classifications of cruiser, destroyer, frigate, corvette or similar based more on politics than clear distinctions. What Work recommended was similar to the old system of classifying ships by guns. In this case, missiles instead of guns. First-rate warships (>100 BFM), second-rate (90-100 BFM), third-rate (60-89), and on down to unrated warships with negligible missile capability. For this analysis, the author augmented Work’s lower ratings with fourth-rate (40-59 BFM), fifth-rate (20-39 BFM), sixth-rate (6-19 BFM), and unrated as < 6 BFM. This reclassification produces the following fresh perspective:

There is a clear USN preference for heavily armed surface combatants compared to potential adversaries. The one Russian Kirov is rated as a first-rate warship, but is barely a blip compared to the U.S. Ticonderoga-class cruisers. The Chinese Type 055 arriving into service will provide China with first-rate warships as well, but still a fraction of the number the USN has. The two U.S. Zumwalt DDGs in 2019 are third-rate ships-of-the-line, but have scores of better armed compatriots compared to the Chinese third-rate vessels. None have a fifth rate combatant (6-20 BFM) unless it is a submarine.

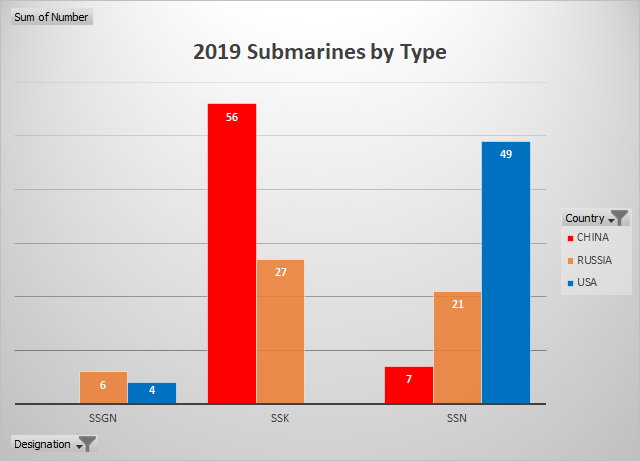

The chart above could spark concern at the rough parity in attack submarines between the U.S., Russia, and China. However, when broken down by type of submarine, the picture changes. The USN relies exclusively on nuclear-powered submarines to provide longer range, greater speed, and more submerged endurance compared to diesel or air-independent propulsion (AIP) submarines. This is because the U.S. plans an “away game” with submarines deployed far from U.S. shores, while Russia and China expect to be using their larger conventional submarine fleets close to home.

When the metric of BFMs (including torpedoes) is applied, the U.S. is also shown to have a significant lead in subsurface firepower. While the U.S. has fewer SSGNs than Russia, they carry far more missiles per submarine. The three Seawolf SSNs also have an extra-large torpedo load, as do Los Angeles and Virginia class SSNs fitted with vertical launch tubes, to give them more weapons than other subs their size. This allows them to stay in the fight longer before returning to reload. Newer Virginia class submarines will have the Virginia Payload Module (VPM) installed, further increasing their firepower.

Of course, any single metric will fail to capture the power of a fleet. Informed opinions will differ on the correct offensive and defensive load mix for a warship, or the qualities of a Harpoon ASCM compared to a P-270 Moskit, 3M-54 Club, or YJ-18. Some of these issues are discussed by Alan Cummings in his 2016 Naval War College Review article on Chinese ASCMs in competitive control. In that article, he shows that for anti-ship firepower, U.S. surface vessels are severely over-matched. However, after 2016, VLS options for surface strike (SM-6 and Maritime Strike Tomahawk) have become feasible. Since the mixture of weapons in a VLS tube battery is variable, the number of cells may now provide a better metric than calculations assuming weapons loads. In addition, one must consider crew quality, training, and readiness as components of fleet power. National character and experience as a sea power also come into play. However, all of these qualities are hard to ascribe metrics to, and arms control treaties and analysts focus on measurable and verifiable metrics.

Conclusion

In the end, a fleet must be measured against what it is expected to do. For power projection abroad, a large number of BFMs (or carriers supporting strikes) would be more capable of performing the mission. Close to home, vessels can more easily return to friendly ports to rearm BFMs, so the total at sea may be less important. Even at equal numbers of BFMs, a fleet concentrating them on a smaller number of high-capacity platforms would be less able to control sea-space than a fleet that spread the same number of missiles over a half-dozen combatants. The more distributed fleet would also be more tolerant of losses. Currently, the USN has its power concentrated in high-end warships, be they carriers, large surface combatants, or nuclear submarines. However, this also makes the USN susceptible to major losses, especially if defenses don’t work as well as expected.

The U.S. has a significant lead in BFMs, but also has global commitments which may drastically reduce how many BFMs can be committed to a particular theater. In the western Pacific, the PLAN is rapidly narrowing this lead. As the United States builds towards a 355-ship Navy, it will need to carefully consider the missions required and, in wartime, the firepower required, to accomplish them.

Commander Keith “Powder” Patton is the Deputy Chair, Strategic and Operational Research Dept (SORD) at the Naval War College. The views expressed in this piece are his own and do not represent the official views of the Navy or the Department of Defense.

Featured Image: September 3, 2005. US Navy (USN) Sailors aboard the Arleigh Burke Class (flight I); Guided Missile Destroyer, USS FITZGERALD (DDG 62) inspect the MK 41 Vertical Launching System (VLS) for water to prevent electrical failure. (Photo by: PHAN Adam York, USN)