By CDR Augusto Conte, Spanish Navy, and Gonzalo Vázquez

In the latest Notes to the CNO series run by CIMSEC back in September 2023, we argued that in an increasingly contested and complex maritime environment, “the next Chief of Naval Operations must strive to find new ways to capitalize on allied capabilities to succeed at sea.” A few weeks later, Hamas’ attack on Israel set the scenario for what has now become one of the most serious maritime crises in decades, further highlighting the need to capitalize on allied naval capabilities to build a more credible deterrent posture and protect our collective interests at sea.

Over the last six months, the spillover of the conflict’s consequences into the Red Sea region has seen the Yemen-based Ansar Allah (the Houthis) launch an unprecedented campaign of attacks against maritime commercial shipping. The notorious impact of their actions has once again underscored the need to strengthen naval interoperability among allied navies, including the development of high-intensity naval capabilities, as well as the need to deepen naval coordination between the European Union (EU) and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) at a higher level – in a way that the efforts and resources of both can be maximized.

Red Sea Crisis Overview

Since October 2023, Houthi attacks against commercial shipping have greatly deteriorated the security environment in the Red Sea, prompting leading shipping companies like Maersk or CMA CGM to redirect their vessels around the Cape of Good Hope – a decision translating into an increase in costs and transit times. Between October 31st and November 15th, Ansar Allah claimed six missile and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) attacks on Israel’s Eilat, though their weapons lacked the range to strike deep into Israel. They have also sought to disrupt Israeli shipping with UAVs and cruise missiles, and on November 19th, several militants used a helicopter to board and seize an Israeli-owned cargo ship transiting the Red Sea.

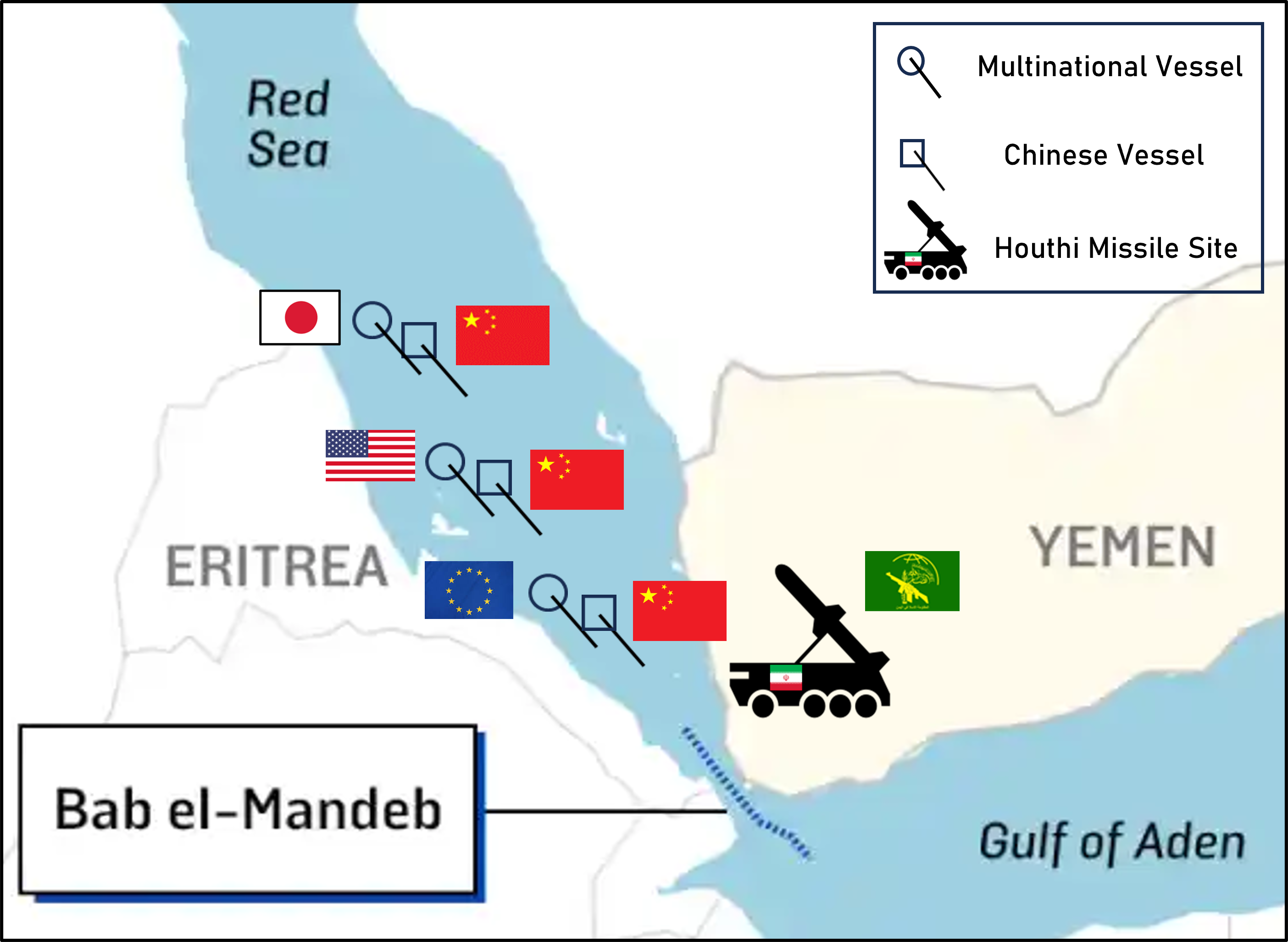

With the launch of Operation Prosperity Guardian in December 2023, the collective effort of several nations to deter aggressions has not managed to suppress completely Houthi efforts. The combined naval assets from the US, UK, France, Italy, and Germany have successfully neutralized several threats, managing to shoot down UAVs, intercept missiles, disable small hostile speedboats, and destroy unmanned surface vehicles (USVs). Additionally, at least one unmanned underwater vehicle (UUV) has been eliminated by these multinational forces.

In spite of these efforts, attacks have not been entirely stopped. Weeks after the launch of Prosperity Guardian, the European Union initiated Operation Aspides in mid-February, its own naval deployment focused on safeguarding maritime traffic in the region. Aspides, however, discarded the option of carrying out attacks against land targets from its inception, limiting it to escorting vessels across the region and providing missile defense when necessary.

The enhanced maritime security presence seeks to deter further attacks by the Houthi rebels in Yemen against commercial vessels transiting vital shipping lanes. It demonstrates a coordinated international commitment to maintaining freedom of navigation and protecting crucial maritime trade routes in the strategic Red Sea area. Altogether, these efforts by allied navies to mitigate the negative consequences of Houthi attacks with their deployments to the Red Sea offer valuable strategic and operational lessons to NATO. From among them, this article aims to focus on the crucial importance of allied maritime interoperability and the need for it to be constantly exercised and properly maintained.

The evident proliferation of enemy firepower over the last years has directly resulted in the growth of hostile sea denial capabilities, including in the increasingly-contested littorals. The Red Sea crisis provides further evidence to the argument that in spite of current revitalization efforts and the desire to strengthen their high-intensity naval capabilities, NATO navies remain under-resourced and under-prepared to meet the existing challenges to their individual and collective interests at sea. Furthering this point are the words of Jérome Henry, commander of the French FREMM Aquitaine, following their forced abandonment of the Red Sea region in April:

“We didn’t necessarily expect this level of threat. There was an uninhibited violence that was quite surprising and very significant. [The Yemenis] do not hesitate to use drones that fly at water level, to explode them on commercial ships, and to fire ballistic missiles.”

Allied Interoperability in an Increasingly Contested Maritime Environment

NATO defines interoperability as “the ability for Allies to act together coherently, effectively, and efficiently to achieve tactical, operational, and strategic objectives.” In the naval realm, one of the main obstacles often underscored in this regard are the different types of warships, command and control (C2) systems, weapons systems, etc., which complicate the integration efforts. Yet, as the Alliance itself suggests, “interoperability does not necessarily require common military equipment. What is important is that equipment can share common facilities and is able to interact, connect and communicate, exchange data and services with other equipment.”

The 2022 U.S. National Security Strategy (NSS) introduces a prominent concept in terms of interoperability: “Integrated Deterrence.” This approach involves combining various capabilities (economic, diplomatic, military, among others) to persuade adversaries of the high costs that any aggression against the United States or its allies would entail. It reflects a national security perspective that increasingly considers factors beyond the purely defensive realm. It encompasses several aspects: multi-domain integration, multi-regional integration, full-spectrum integration, inter-agency integration, and most importantly, allied integration. But more importantly, it also promotes collaboration and coordination with allies in areas such as investments, capability development, and technological and economic strategies, among others, to strengthen deterrence and collective defense capabilities.

Houthi attacks have proven to be manageable by allied navies, with the U.S., France, Italy, and the UK successfully intercepting a high number of anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs) – a first in naval history – and kamikaze UAVs. The performance of these ships’ crews, some of which have had to endure extended deployments away from home in their commitment to protecting freedom of navigation, has been commendable. Nevertheless, such performances have also shown that many of the current and near-future challenges to NATO’s maritime posture demand a collective response in order to be properly addressed; and they cannot be managed only by a small number of members.

Crisis management operations have been one of the central commitments of allied navies for almost two decades, and one of the pillars of the Allied Maritime Strategy. On certain occasions, these operations have revealed shortfalls in participating navies’ capabilities and preparedness. For example, NATO’s intervention in Libya in 2011 “quickly revealed mismatches and critical capability shortfalls in the alliance.” Throughout the duration of Operation Unified Protector, “it became clear that only the US possessed the capability to execute a fully-fledged SEAD/DEAD (suppression/destruction of enemy air defenses) campaign,” underlines Sebastian Bruns.

Unlike 2011, though, NATO has not formally launched an operation in the Red Sea, with the U.S. deciding to launch Operation Prosperity Guardian under the auspices of the Bahrain-based Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) Task Force 153 instead. Still, the failure to deter the Yemen-based terrorists from attacking merchant vessels in the vicinity of Bab El-Mandeb and the southern Red Sea has shown the U.S. cannot (and it should not) do it alone.

The nature of modern threats, including the use of ASBMs for the first time in history, the resurgence of Somali piracy in the Horn of Africa, and the significant proliferation of enemy firepower have reminded NATO navies that the existing challenges in and around the Alliance’s maritime neighborhood will demand closer cooperation among its naval services to properly manage the mix of high-intensity and low-intensity naval tasks to be carried out. To succeed in doing so, the Standing NATO Maritime Groups (SNMGs) stand out as a valuable tool with the potential to allow for important developments.

Strengthening Allied Interoperability at Sea

Current NATO naval exercises, including the ongoing Steadfast Defender 24, offer additional opportunities to strengthen ties in naval warfare-related tasks, but interoperability needs to be trained and developed on a more regular basis and at a deeper level. Aside from the current deployments to the Red Sea, where several NATO navies are operating simultaneously, other potential avenues for doing so include the deployment of NATO warships in U.S. deployments –especially with its CSGs– and the SNMGs.

To maintain credible deterrence, allied navies must modernize their naval capabilities, especially in areas such as air and missile defense, electronic and cyber combat systems, and sea-based force projection capabilities. Such modernization must be done in close coordination among allies to maximize interoperability, addressing common shortfalls such as the inability to reload at sea (a problem which, as previously mentioned, recently forced French FREMM Aquitaine to abandon the region after running out of munitions). It is crucial that NATO and its allies work to develop updated joint naval doctrine and tactics to meet emerging threats in the littoral environment. This includes the integration of swarm capabilities, missile defense, anti-submarine warfare, and information operations, among others. A robust joint doctrine would lay the foundation for true naval interoperability. Something resemblant to the Cold War days’ Striking Fleet Atlantic (STRKFLTLANT) to develop it and provide a forum where allied navies can regularly exercise their high-end naval warfare should also be considered.

In a 2019 Proceedings article titled “Rebuild Allied Maritime Interoperability”, its authors provided a number of reasons for which NATO must focus its efforts in strengthening naval interoperability, focusing on the role that the U.S. Navy can play in leading such efforts. In their view, “for the U.S. Navy, including allied ships enables it to close gaps between U.S. and NATO tactics, techniques, and procedures and to adapt a firmly U.S.-oriented battle rhythm to NATO standards and platforms.” The deployment of both the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower and the USS Gerald R. Ford carrier groups to the Gulf of Aden and the eastern Mediterranean, would have been a great opportunity for doing so.

The Standing NATO Maritime Groups are another important instrument with which to develop and exercise naval interoperability. Yet, much of their potential remains untapped, pending an update that moves them from their post-Cold War structure and missions towards a stronger emphasis on high-intensity naval warfare. SNMGs’ deployments over the past decades have been a good instrument to maintain a certain level of interoperability, but the scope of their missions has been limited to activities in the lower-end of the intensity spectrum. Moreover, their size shrank notably during the two decades following the end of the Cold War, leaving them with “sluggish participation rates” that are insufficient for the current strategic challenges that NATO is now facing at sea. As CNA analyst Joshua Tallis has argued on more than one occasion:

“In this time of high tension, very few combatants are attached to the alliance’s two major standing naval groups. As of mid-December, three combatants formed Group One […] Only two combatants comprised the Group Two. This is not an overwhelming force presence […] Rather, it is a shadow of the alliance’s historic approach to maritime security.”

Operation Prosperity Guardian has effectively demonstrated that NATO navies are no longer able to deter their adversaries as they did back in the 1990s and early 2000s. Nor would an operation as Desert Storm be feasible today given the current state of NATO air and naval assets. Therefore, lessons from the Red Sea provide a helpful lens to re-examine the current missions and structure of the SNMGs, suggesting a much-needed structural shift to reduce their focus on low-intensity and constabulary missions and enhance the development of high-intensity naval capabilities while seeking a higher number of ships available to be deployed.

As part of that shift, the challenges associated with operating in a contested littoral environment, as is the Red Sea at this moment, have also brought back timely lessons on littoral warfare. According to US Naval War College professor Milan Vego, “a blue-water navy now faces much greater and more-diverse threats in the littorals than in the past. This is especially the case in enclosed and semi-enclosed seas, such as the Persian (Arabian) Gulf.” Even in the absence of a submarine threat that requires ship crews to devote part of their efforts and assets towards anti-submarine warfare (ASW), allowing them to focus almost exclusively on anti-air warfare, Red Sea operations indicate future littoral warfare campaigns will become increasingly demanding.

As ascertained by Jennifer Parker and Royal Australian Navy’s Vice Admiral Peter Jones, “littoral operations not only demand a prominent level of Combined and Joint interoperability, but also stress the need for an integrated approach to operations.” The likely potential for swarm attacks with both UAVs and USVs (the latter featuring in the Black Sea) has made the littoral an even more contested space, and demands stronger efforts to adapt the SNMGs so that NATO navies can be able to manage such kinds of threats in the near future. Although in the case of the Red Sea they have mostly come as UAV attacks that allow for their effective destruction, there have been several instances in which warships have had to rely on their Close-In Weapons Systems (CIWS) to down the drones. It is worth asking, then, what would happen should these mishaps take place when facing a combined swarm attack of UAVs and USVs that overwhelms the ship’s defenses. It is also worth asking whether the SNMGs would be in a position to fight off an attack of such characteristics.

Moving Forward

In short, the Red Sea crisis has reminded the world once again about the importance of maritime commercial connectivity for the global economy. It has, together with the ongoing naval war in the Black Sea, reminded NATO navies that the challenges of this “maritime century” will require bigger and stronger navies, capable of deploying together and addressing threats against them in a joint fashion, including in the highly contested littorals.

Moving forward, Houthi rebel attacks on commercial shipping traffic in the Red Sea are bound to intensify as part of the Iranian response to the Israeli attack on Damascus. The crisis in the Red Sea could escalate, further affecting crucial maritime trade routes and jeopardizing freedom of navigation in the region. In this regard, the relationship between the EU and NATO has been the subject of debate in Europe, especially with regard to the development of the European Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP) and its cooperation with NATO.

Integration with allies and partners through investments in interoperability and joint capability development, cooperative posture planning, and coordinated diplomatic and economic approaches should be a common goal for NATO allies. We must work together in the Red Sea, with both operations from the EU and NATO, to increase our interoperability and build a truly integrated deterrent. This will require the EU’s soft power influence, but above all, it will require NATO to develop more robust high-intensity naval warfare capabilities, working closely together with the SNMGs (although something resemblant to STRKFLTLANT should also be seriously considered).

At a time when multiple sources of instability with the potential to escalate combine with other low-intensity but still demanding challenges, NATO must strive to build up its deterrent posture and leverage the naval capabilities currently available under a collective effort. For such purposes, allied naval interoperability must be thoroughly exercised and evaluated. If properly assessed and examined, all lessons drawn from naval actions in the Red Sea will provide valuable input on how to readapt NATO’s naval forces for a renewed era of great power competition and to better cope with the threats present in the Alliance’s maritime backyard.

CDR Augusto Conte is a submarine and electronic warfare officer serving as a senior analyst with the Spanish Naval War College’s Center for Naval Thought. He has served as Commanding Officer of the Patrol Vessel Formentor, Executive Officer of the Galerna-class submarine S-72 Siroco, and as Deputy Director of the Navy Submarine School.

Gonzalo Vázquez is a junior analyst with the Spanish Naval War College’s Center for Naval Thought.

Featured image: The guided-missile destroyer USS Mason sails alongside the Japanese destroyer Akebono in the Gulf of Aden, Nov. 25, 2023. The USS Mason is deployed to the U.S. 5th Fleet area of operations to support maritime security and stability in the Middle East. (Image credit: Petty Officer 3rd Class Samantha Alaman.)