By Bill Bray

A few years ago, when I was serving as a senior Navy fellow, a technologist on the team predicted that sailors soon could be wired, fitbit-style, to such an exquisite degree that everything about them, from moods to future bad choices, could be known, tracked, logged, and used. As he explained, this technology would be used for everything from emergency intervention to evaluation writing. In fact, the evaluations would practically write themselves. He was young and, to my knowledge, had never led anyone, yet presented with an almost breathless certainty.

Those of us who had spent years in the fleet could be forgiven for being skeptical, or even surprised, since we may think we know people—who they are, what makes them tick, or why they do the things they do. As much as I was surprised by the young technologist’s easy confidence, as he spoke I found myself recalling an experience I had as a young officer. With more than three years on board my first ship, I thought I knew the sailors I led and worked with very well. Know your people was a leadership mantra even back then, although it had yet to be taken as far as the young technologist’s predictions. What I could not predict was that early one morning, one of my sailors would wake up at his off-base San Diego apartment, retrieve his legally owned handgun, and shoot and kill his two roommates while they slept.

When first visited in jail, he said very little beyond that he felt he had the right to do what he did. While a bit aloof and arrogant, he was otherwise quiet and mild-mannered and had never been in trouble. A few days after the murders, I wondered to my captain how such an unassuming young sailor could do something so horrible. He said, perhaps now in contradiction to the technologist with whom I would later work, “you will never know.”

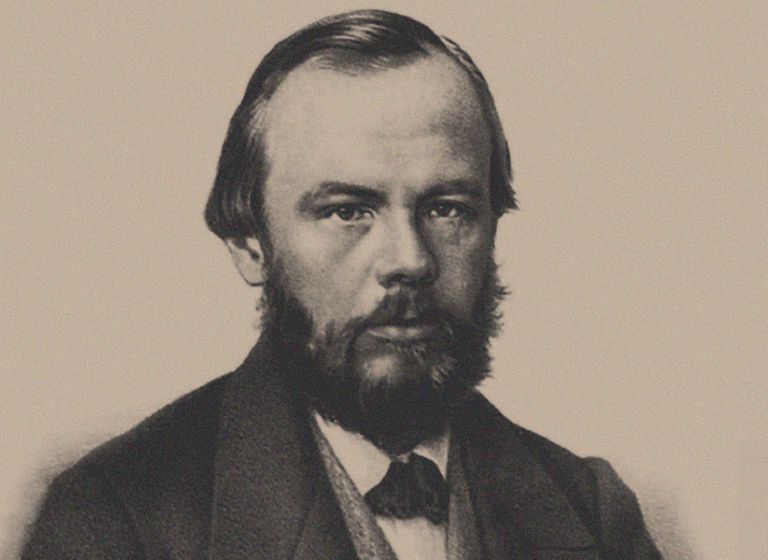

One who wrestled with a mid-19th-century version of the technologist’s optimism was the great Russian writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Naturalism was then the rage (Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published in 1859). There was great confidence that man could be understood (entirely) through observation and experimentation (the scientific method). For example, one of Dostoyevsky’s contemporaries, Ivan Mikhailovich Sechenov, published The Reflexes of the Brain (1863) based on his research with frogs (his main claim was that all human behavior could be explained as reflexive action). Dostoyevsky had seen too much in life by then to believe it. He thought it not just nonsense, but dangerous nonsense. Its implications for political and social life were terrifying.

I first read Crime and Punishment, Dostoyevsky’s first novel of his major literary period, a few months after leaving my first ship. As I read it and ventured into Dostoyevsky’s world for the first time, the sailor and his fate were front of mind. With crime, the why is always more difficult to know, and more fascinating to contemplate, than the what. Military justice deals primarily with the crime itself, with the important goals of deterring criminal activity and maintaining good order and discipline. But at a grander level Dostoyevsky was not writing about crime and the criminal. Through a dramatic narrative, he demonstrates how human intentions, motivation, subjective experience, and behavior are not knowable, let alone explainable, solely through physical observation. They cannot be categorized into “data sets,” to borrow a more contemporary term. Dostoyevsky helped me be skeptical of, if not the whole human resources field, at least the faith that technology can ever make human performance and behavior predictable.

Ideas were not inconsequential for Dostoyevsky. Crime is often a phenomenon that begins with an idea. Examining how humans can be swept up by an idea and rationalize crime is a recurring theme—one could say an obsession—for Dostoyevsky throughout his major literary period beginning with Crime and Punishment (1866). He was a gifted dramatist, so much so that in Crime and Punishment, while there is no question of the student Raskolnikov’s guilt or that he will not escape earthly justice, the reader almost hangs on every paragraph, searching for answers to the why of the crime—and to eternal questions, such as can murder ever be justified, and for what? Crime and Punishment might be the greatest whydoneit ever written.

The Mystery of Man

Hemingway famously wrote in Green Hills of Africa that “Dostoevsky was made by being sent to Siberia. Writers are forged in injustice as a sword is forged.” Indeed, Konstantin Mochulsky, one of the greatest Dostoyevsky biographers, writes in the introduction to Dostoyevsky: His Life and Work, “The life and work of Dostoyevsky are inseparable. . . Dostoyevsky was always drawn to confession as an artistic form. His works unfold before us as one vast confession, as the integral revelation of his universal spirit.”1

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky was born 30 October 1821. His father, Mikhail Andreyevich, was a doctor, and by most accounts could be stern and moody. After Dostoyevsky’s mother, Marya Fyodorovna, died in 1837 of tuberculosis, father Mikhail retired to his country estate, where his drinking and treatment of serfs worsened. In 1839, while Dostoyevsky was enrolled in the Nikolayev School of Military Engineering in St. Petersburg, the serfs allegedly beat his father to death following one particularly abusive episode (evidence uncovered in the 1970s casts some doubt on this story).2

Dostoyevsky did not care much for engineering. He passed into the School of Engineering more interested in reading writers such as Schiller, Hoffman, Balzac, and Pushkin than in studying mathematics. In The Diary of a Writer (a series of essays he wrote in the 1870s), Dostoyevsky claimed that as soon as they arrived in St. Petersburg in May 1837, he and his brother Mikhail made a visit to the spot where Pushkin died (Pushkin was killed in a duel with his brother-in-law in February of that year).3 By 1839 he knew for certain his calling. That year he wrote Mikhail:

To study the meaning of man and of life—I am making sufficient progress here. I have faith in myself. Man is a mystery. One must solve it. If you spend your entire life trying to puzzle it out, then do not say that you have wasted your time. I occupy myself with this mystery because I want to be a man.4

By the mid-1840s, Dostoyevsky was becoming known in St. Petersburg literary circles. He published his first book, the novella Poor Folk, in January 1846. Shortly thereafter, he requested release from military service. He then published the The Double in late January. In the next two years, he associated himself with at least two political-literary groups.

The 1840s were heady political times in Europe, and affiliating with such groups was risky in imperialist Russia. One group was founded by Mikhail Petrashevsky, long a proponent of social and civil reform in Russia. In 1848, revolution swept western Europe and the Tsar Nicholas I became more fearful of losing his grip on power. In April 1849, members of the Petrashevsky circle, including Dostoyevsky and his brothers Andrey and Mikhail, were arrested and jailed in the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg (Dostoyevsky’s brothers were released within two months for a lack of evidence). A military court found Dostoyevsky guilty in November and recommended he be executed. However, the Tsar agreed to commute the sentence, but only after the writer endured a mock execution on 22 December at Semenovsky Square. The Tsar’s messenger arrived just in time to announce the commutation—“Nicholas carefully orchestrated the scenario on this occasion to produce the maximum impact on the unsuspecting victims of his regal solicitude.”5

Dostoyevsky spent four years of hard labor in a prison camp in Omsk, followed by five years of military service. One can scarcely imagine how ghastly life in a Siberian prison camp was in the 1850s. Dostoyevsky’s first letters to his brother on release in 1854 (he was unable to correspond while in prison with one exception) and his later account in Notes from the House of the Dead (1861) vividly describe a horrifying penal existence.

Yet the “unspeakable, interminable suffering” was the turning point in the writer’s spiritual development.”6 In many letters Dostoyevsky describes his time in prison as one of introspection and “regeneration.” Dostoyevsky could never reconcile his religious faith with the radical rationalism so prevalent in the mid-1800s. “The ‘magic of extremes’ which had shaken Dostoyevsky’s personal life made him follow man into the darkest corridors of his mind, where nothing remains hidden and where the only way out is the flight into God’s open arms.”7

When he returned to St. Petersburg in 1859, he found the intellectual environment brimming with this radical rationalism. The “vibrational stew” he encountered, according to James Parker, included “nihilism, egoism, materialism. . . The human is being reconceived.” Reason is pitted against faith, against the irrational. What is more truthful? What is more authentic? What is man capable of if he believes only in his capacity to reason? From where comes the moral law in a world where man is the only lawgiver? These questions plagued Dostoyevsky. As Mochulsky put it: “And thus began the struggle between faith and reason in the writer’s consciousness, thus arose the fundamental problem of his philosophy.”8

From Mystery to War

What I should have first read, before Crime and Punishment, is Notes from Underground, published in 1864 in the January and April issues of Epoch, the second magazine Dostoyevsky ran with Mikhail (the first, Vremya [Time] was closed by the censors the year prior).

At just 125 pages, Notes from Underground is the philosophical premise of the author’s great works. In it, we find a thundering cry from the wilderness, an author whose “regeneration of convictions” and long years observing man’s capacity for cruelty and depravity coalesced into a fiery conviction to save humanity from destroying itself. In today’s parlance, Dostoyevsky was a culture warrior—a reactionary who saw the state of man in the mid-nineteenth century as corrupt and sick, an outcome of his almost breathless arrogance before nature and God. Society was deep in an existential crisis. Its foundations were beginning to crumble. Few seemed to recognize the coming apocalypse.

Dostoyevsky was at war with the prevailing intellectual current of his time, one that placed humanity’s fate squarely in the hopes of a scientific positivism that held that understanding man’s character, nature, and behaviors can be derived through sensory experience (observation), experimentation, and reason. Change man’s environment for the better through science, and man’s nature will change for the better.

One of Dostoyevsky’s antagonists was the socialist Nikolay Gavrilovich Chernyshevsky, who in 1863 published the utopian novel What Is to Be Done? No less than V.I. Lenin would point to Chernyshevsky’s novel as a pivotal influence. Richard Pevear, in the forward to the translation of Notes from Underground he and his wife Larissa Volokhonsky published in 1993, explains that Dostoyevsky initially planned to write a review of What Is to Be Done? in Epoch, but decided that literary critique alone would be inadequate. It required the force of an artistic response, consistent with Dostoyevsky’s conviction that only through art can the human condition be understood in a way that could expose the pretensions and falsehoods of a thinker such as Chernyshevsky. Pevear notes:

[Chernyshevsky’s hero] is the voice of the healthy rational egoist, the ingenuous man of action. Dostoyevsky takes up the challenge. Though Chernyshevsky is not mentioned by name in Notes from Underground, his theories, and in particular his novel, are the most immediate target of the underground man’s diatribes and of Dostoyevsky’s subtler, more penetrating parody.9

Rational egoism was Dostoyevsky’s bête noir. He knew where this unquestioned belief in science to answer all questions was heading, and it was not pretty. His tortured, mysterious characters can be seen as irrationality resisting science’s dogmatic adherents. His underground man mocks Chernyshevky:

Oh, tell me, who first announced, who was the first to proclaim that man does dirty only because he doesn’t know his real interests; and that were he to be enlightened, were his eyes to be opened to his real, normal interests, man would immediately stop doing dirty, would immediately become good and noble, because, being enlightened and understanding his real profit, he would see his real profit precisely in the good, and it’s common knowledge that no man can knowingly act against his own profit … Profit! What is profit? And will you take it upon yourself to define with perfect exactitude precisely what man’s profit consists in? And what if it so happens that on occasion man’s profit not only may but precisely must consist in sometimes wishing what is bad for himself, and not what is profitable? And if so, if there can be such a case, then the whole rule goes up in smoke.10

Of course, Dostoyevsky notes, man acts against his own self-interest all the time. This is natural, if incomprehensible, behavior. Man is at once rational and irrational. The observation/experimental method had no answer for this (modern neuroscience has not provided an answer either).

Crime and Punishment

Crime and Punishment is the epic, full-bodied drama that poured out of Dostoyevsky in a frenzy of creative activity following the 1864 deaths of his first wife and his brother Mikhail, and was inspired, in part, from his reading about the French murder trial of the sociopath Pierre-Francois Lacenaire. In July 1865, he was in Wiesbaden on his third trip abroad. He had gambled away what savings he had and was asking acquaintances, including the Russian writer Ivan Turgenev, to loan him money. At some point that summer he abandoned work on The Drunks (the story of the Marmeladov family was ultimately incorporated into Crime and Punishment) and began work on what he had indicated to Mikhail as early as 1859 would be a “confession” novel, one he had first thought of while in prison when “lying on a bed of wooden planks, in an oppressing moment of melancholy and self-dissolution.”11

In September, Dostoyevsky wrote a letter to the prominent editor Mikhail Katkov in which he pitched the novel as a “psychological account of a crime,” going into great detail about how most of the dramatic action would not be about the crime itself, but how the protagonist navigates the aftermath of the crime morally and spiritually.12 He had finished a draft of the novel by late November when back in St. Petersburg, but was not happy with the outcome, and began rewriting it. The first part of what became a six-part novel was published in January 1866 in The Russian Messenger. Parts two and three followed in the ensuing months, and the entire novel was published by the end of the year.

Dostoyevsky’s characters are strange, outlandish, and even grotesque. In Crime and Punishment, we are not on lavish estates, in drawing rooms, or at grand balls—we are in the gutter, at the edge of civilized society, in a gloomy atmosphere of torment, sickness, and despair. Many characters are given to exaggerated emotional outbursts and behaviors. As William Hubben wrote, “All of Dostoyevsky’s stories belong to the literature of extreme situations. An ominous restlessness broods over the men and women in his novels. Frequently their reaction to seemingly small incidents is excessive, and events take a most unexpected turn.”13

Dostoyevsky is often accused of being an overbearing writer who preached that the path to salvation was through hardship and suffering. In Russian, this outlook is known as dostoyevshchina, or as Y. Karyakin explains, “a masochistic wallowing in suffering, a pathological acceptance of the ugly in the world … a sick conscience which derives comfort from the belief that there can be no easy conscience…”14

Dostoyevsky’s protagonist Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov is perhaps an embodiment of dostoyevshchina—at once intelligent and aloof, easily irritable, with a disdain for people in general. He is tormented, suffering from some inner turmoil. He is “functionally insane,” according to Parker. But even when we learn he intends to commit cold-blooded murder, he is not wholly unlikeable. He has genuine empathy—for the Marmeladovs, for example, especially the oldest daughter, the prostitute Sonya—and a deep love for his mother and sister, one that is ostensibly the motive for the crime. He has dropped out of school and needs money to take care of his mother (Pulkheria Alexandrovna) and liberate his sister (Avdotya Romanovna, or Dunya) from marrying the corrupt businessman Pyotr Luzhin, which he believes she is only doing to help him return to school.

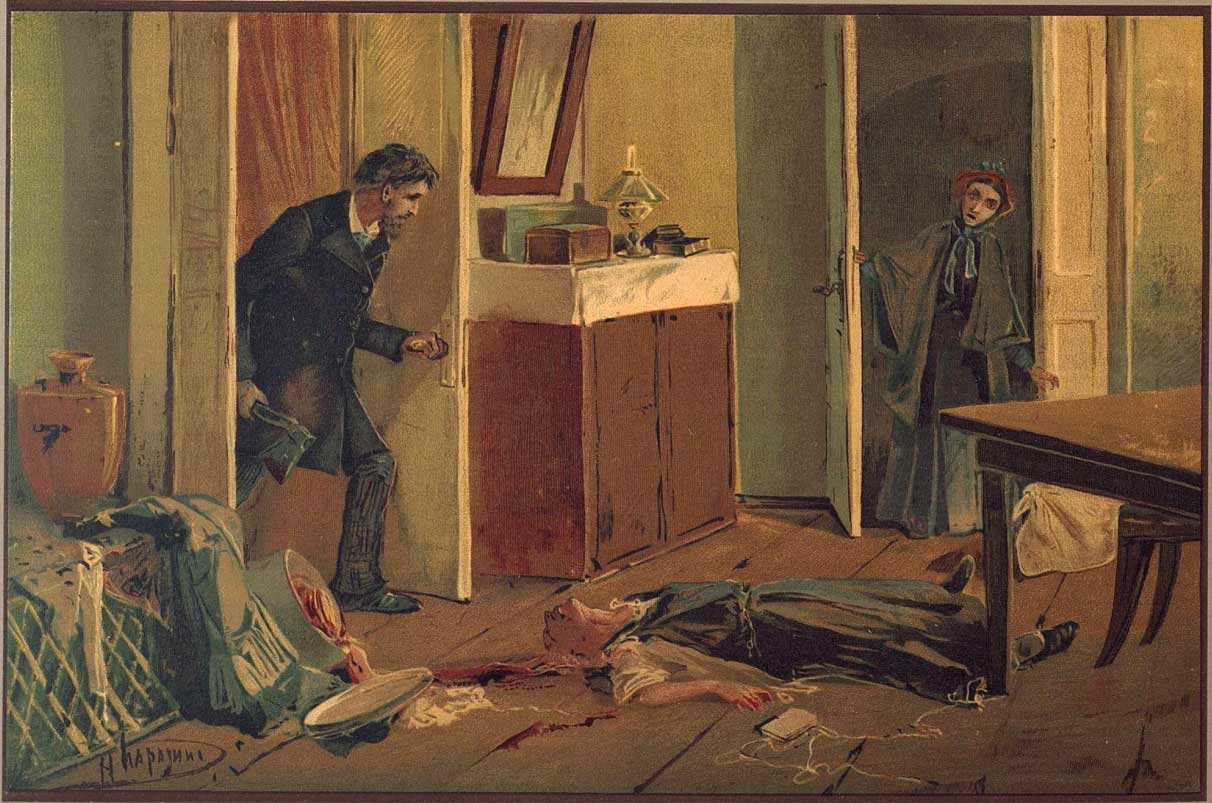

At the novel’s outset, Raskolnikov is already in the throes of crisis. Although his struggle is not unique, it is universal. He is Dostoyevsky’s example of the new idealists who suffer an “infirmity of notions, having come under the influence of some of those strange, ‘incomplete’ ideas which go floating about in the air…”15 The only way out of his predicament is to murder the old money lender Alonya Ivanovna, a despicable, vile woman he believes the world will be better off without. He commits a gruesome ax murder and, when walked in on by Alonya’s younger sister Lizaveta, he kills her too.

The novel’s remaining five parts deal with Raskolnikov’s anguish and looming fate. The police investigator, Porfiry Petrovich, suspects Raskolnikov not only has committed the crime, but that his conscience would eventually get the better of him and lead to a confession. What primarily holds readers’ interest is that they want to know what Petrovich wants to know—why did he do it.

The answer flows from Raskolnikov’s own philosophical quest. Can an evil act be justified if it produces good consequences? Are some people, by virtue of their greatness, permitted to transgress the moral law that bounds everyone else? He thought so, and the act was meant to prove it. According to Karyakin, “Dostoyevsky’s hero is a man obsessed by an idea, a man in whom Dostoyevsky looks for and finds a human being wounded by an idea, killed by an idea or resurrected by it.”16

Mochulsky claims that Crime and Punishment would have been more accurately titled Crime and Expiation: “Raskolnikov is not only the compositional, but the spiritual center of the novel … the tragedy springs up in his soul and the external action only serves to reveal his moral conflicts.”17 Raskolnikov tries to put himself above the moral law. But he cannot, just as his actions cannot be explained as reflexes in his brain.

A Lesson on Mystery and Fantastical Predictions

Why did my sailor commit a double homicide? Was he perhaps driven by something more than passion and rage at a perceived slight? Was his crime an act against his own self-interest? An illustration of man’s simultaneously rational and irrational mind in action? Much to that young, optimistic technologist’s dismay, we will likely never know. Human behavior is complex and irreducible to data and formulas, something human resources professionals and data scientists rarely want to hear. If anything, Dostoyevsky’s work and life are a testament to the inherent mystery of human behavior, the irreducible complexity of actually knowing someone well.

Recent progress in artificial intelligence has spawned, again, some fantastical predictions of data-driven talent management processes that will categorize subordinates (workers) to such a fine degree that near-total behavioral predictability will be possible. Human performance data will be continuously collected in the workplace, categorized and collated, populating digital profiles and giving future leaders a “game-changing” technological toolset to know their people. But before young leaders believe that will happen, they should read Crime and Punishment. Dostoyevsky may give them cause for skepticism. And that could be a good thing.

Bill Bray is a retired Navy captain. He is the deputy editor-in-chief of the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings magazine.

References

1. Kostantin Mochulsky, Dostoyevsky: His Life and Work (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1967), xix.

2. Joseph Frank, Dostoevsky: The Years of Ordeal, 1850–1859 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990), 85–88.

3. Mochulsky, Dostoyevsky: His Life and Work,

4. Mochulsky, 17.

5. Frank, Dostoevsky: The Years of Ordeal, 1850-1859, 51.

6. Mochulsky, Dostoyevsky: His Life and Work,

7. William Hubben, Dostoyevsky, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Kafka: Four Prophets of Our Destiny (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1952), 68.

8. Mochulsky, Dostoyevsky: His Life and Work,

9. Richard Pevear, Forward to Notes from Underground (New York: Vintage Books, 1993), xiii-xiv.

10. Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Notes from Underground, translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (New York: Vintage Books, 1993), 20–21.

11. Mochulsky, 271.

12. Mochulsky, 272.

13. Hubben, Dostoyevsky, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Kafka, 64.

14. Karyakin, Re-reading Dostoyevsky (Moscow: Novosti Press, 1971), 7.

15. Fyodor Dostoyevsky to Mikhail Katkov, as quoted in Mochulsky, 272.

16. Karyakin, Re-reading Dostoyevsky, 124.

17. Mochulsky, 299.

Featured Image: “Illuminations in St. Petersburg,” by Fedor Aleksandrovich Vasiliev/Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow Russia,/ Bridgeman Images.

Those who believe human behavior is in principle predictable, do so because the belief is in accord with their experience of the world. Consequence does indeed follow cause, and when we are acquainted with each, the connection, invariably, is obvious. The difficulty lies not in the adequacy of the principle, but in that of the dataset, which is almost always incomplete.

Your young sailor may have been done a grievous injury by his two roommates in a previous life. It is pure speculation, and not disprovable, hence unscientific. If, however, you are willing to admit the premise, it would explain why he was unable to explain his actions, but nevertheless felt justified in them.

Your commander was right, you will never know, but since none of us may ever know in entirety why we do what we do, it behooves us to act with caution, and with humility. It is why we are advised to forgive each other our trespasses. We can never be certain as to whose was the first offence.

Long one …Haven’t read it all …but is well written

No A.I. on planet earth could predict with all data implanted Alexander The Great’s victory at Gaugamela. Why? Human ingenuity! A world changing event. A.i. would fail you!

Ok ,Fyodor

I have something to say to u and to your underground man ( isn’t Fyodor dead ?…)

Why didn’t you do your homework?

U was a sceptisist about Socrates and u questioning him without first ,be able to connect with him and interpret him right ,at the time u was doing this ..Basically you reproduce him and u was a very expanded literature version of his philosophy without know it.If u have read the ” concept of anxiety” it would have been really helpful for u as the father of Exsistencialism -Soren,is the first one who interpeted the mature outcome of his wisdom right and didn’t spend his time trying to cansel him with methods- foregrounds of Nazis Methods – like Freidrich who was in a love and hate” realationship “with him . Then you could have easily c ,that Socrates was the first Exsistencialist ,that all exsistencial philosophy is the interpretation of the ” childish “” one thing I know that I don’t know ” ,so” childish” that even one of the most profound psycologists like u , missed it and it tooks u a large period of time and literature work until you approach it in the right hermeneutical way.I am glad about your interpretation of his quote” an unexamined life is not worth living ” and u did right …u took all the time you needed to interpret the ” mystery of the man ” because u wanted to be a man .Now, should I give answers to your underground man with my poor English ,or should I suggest to the author of this article to connect with the father of Exsistencialism and understand the Grandpa of it,-Socrates .

Should I write the interpretations of ” evil is ignorance – No stupidity is ignorance ,evil is style attitude character …bad boys …yeeaa … Ouaououuu… etc.or explain how suffering helps sometimes …evolution … entropy …escape …create your self etc…and present my self as the ultimate caricature of the” Holly grail of wisdom “that he don’t know to write proper English but he is trying to communicate with it with out caring that is gonna be lost in translation .I can do ,but I thing it’s better to say that Socrates is the central figure that runs all Exsistencialism ,Kierkegaard – Ntostoyefski – Nietzsche etc.and that u will never be able to connect with the questions that the multiple sides of Exsistencialism addressed to the world and r the most important for our life ,without first connect with Socrates through Kierkegaard,or with Kierkegaard through Socrates …No ,I am not a salesman of books of Kierkegaard …just ,when I read him I realise that he can say with two words what others say with thousands and still they r struggling to express it…like me …and sometimes Fyodor…PS please forgive me that I put my name in the same sentence with the name of Fyodor…..

I think u don’t know but u can feel why your sailor did what he did and ,why , although he was right he couldn’t talk about it …

Thank you for your profoundly thoughtful article, Bill Bray, which I just shared with other people. Dostoevsky is much beloved by me, and given the Zeitgeist his brilliant writing is more pertinent than ever. Your piece made me want to read Dostoevsky’s complex and moving novels all over again. Thank you.

Thank you Susan. A comment such as this makes the whole effort worthwhile.

Bill B. – Yet another insightful, superbly crafted writing! Thank you for sharing. Bill G.

I have vastly more fear of the day human predictability reaches such a level that some fool actually tries to implement it, than I have fear of human unpredictability.

Mr. (Capt. Retired) Bray,

I have not read “Crime and Punishment”, yet your article seems to explain the “why” behind Raskolnikov’s crime: “ The only way out of his predicament is to murder the old money lender Alonya Ivanovna, a despicable, vile woman he believes the world will be better off without.”

Is that clear in the book, or is that something the reader has to infer? A somewhat common motivation for murder is “rage against the machine”; maybe the perpetrator cannot get back at the person(s) who tormented him, but he can get back at a weaker, more vulnerable “proxy”.

In any case , a very thoughtful and illuminating article, thanks.

First, thanks for reading.

Second, to your question, “is that clear in the book, …?” It becomes clear because Dostoyevsky, first and foremost a brilliant dramatist, shows us without telling us. You come to understand it through context of Raskolnikov’s situation, specifically his philosophic musings (often captured through inner monologue and even descriptions of his fever dreams). This is not a character driven to murder because of some pedestrian grievance or frustration.

It also helps to read some quality literary criticism of the novel and its author, but I would do that after reading the novel. Don’t spoil the fun too much.