By Adam Greco

For centuries, merchant vessels have passed from the Indian Ocean to Eastern Asia through a small waterway nestled inside Southeast Asia. The Strait of Malacca (SoM) is the Strait south of the Malay Peninsula through which passes over a quarter of the world’s trade.

Three littoral states—Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia—border the Strait. the Strait’s importance derives from its status as one of the quickest routes connecting the Indian Ocean with the Pacific Ocean.

This makes the Strait particularly important for both the United States and China in the realm of international commerce. According to a 2016 report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, roughly $874 billion in exports from mainland China passed through the South China Sea, a body of water that is linked to the Indian Ocean primarily by the SoM. This dwarfs the same figure for the United States, which stood at $83 Billion. Despite this, prominent U.S. allies had high export values as well, such as South Korea ($249 Billion), Japan ($141 Billion), and Germany ($117 Billion). Additionally, it must be noted that not all exports sent through the South China Sea will go through the SoM. Due to its importance, the SoM has become a source of contention not only under the purview of economics, but security as well.

Hazards

On a map the Strait looks wide enough to accommodate any ship, yet there are a few tight spots that many are unable to pass through. This, combined with the Strait’s own prominence, has led to the creation of the “Malacca-max” – a maritime standard that is specifically designed to fit within these confines. Additionally, the constricted areas along the Strait may slow traffic due to crowding. There are no present plans to topographically alter the Strait to accommodate larger vessels, yet this does not necessarily mean that there is no attempt to alleviate local traffic congestion at all.

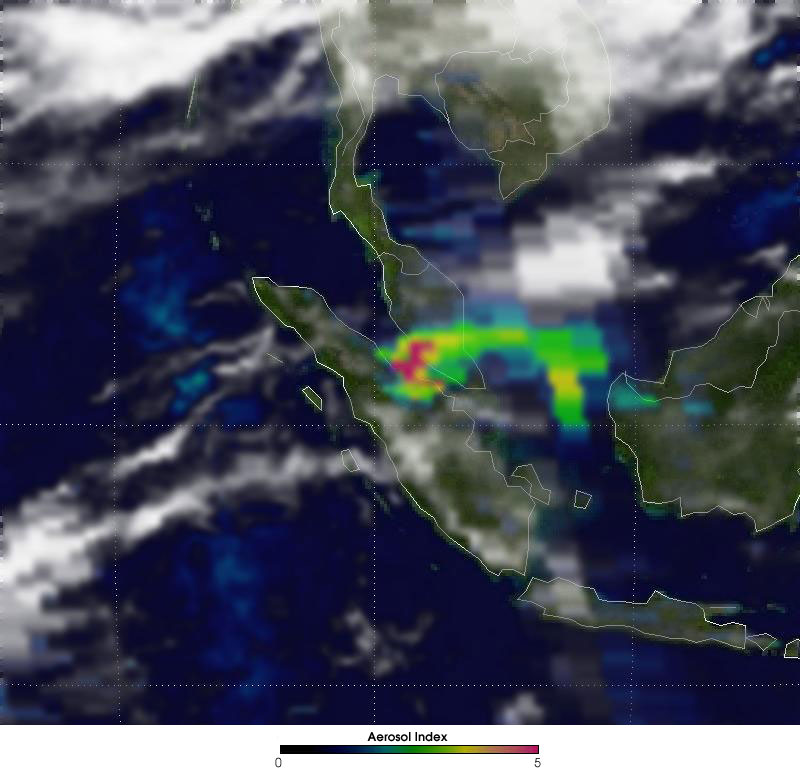

Slower traffic may also be caused by the two other prominent issues: haze and piracy. In recent years, the haze has been the greater of the two problems. Bushfires in the Sumatra region of Indonesia lead to significant amounts of smog for some months of the year that may make maritime transport more difficult. With a movement pattern from south to north across the Strait, this problem also greatly affects Malaysia and Singapore.

Singapore, of the three strait-adjacent nations, has been the most fervent in efforts against the phenomenon. Singapore’s actions to mitigate the haze’s adverse effects have included, but are not limited to creating a task force to help prepare against it and using satellite imagery to alert Indonesia on precise bushfire locations. The haze hardly stops active vessels but instead serves to slow them down, and naturally, fewer obstacles in the region would be beneficial for maritime trade as a whole.

Far more severe than slowing down, piracy may remove a ship from the route entirely. More severe than associated fiscal costs from lost goods is the potential human cost that typically comes with violence from pirates. However, in the context of the SoM, piracy has declined significantly in recent years in both frequency and severity. This is primarily due to the large military presence in the Strait from both the United States and China.

The War on Terror and the Strait

The American War on Terror is commonly attributed to the Middle East, but terrorism is a global threat. Pirates are not commonly thought of as terrorists, though they function in a similar way and pose risks through the lenses of economic costs, human endangerment, and physical control. The U.S. Navy currently works on military exercises with the respective navies of its local partners, Malaysia and Singapore. Though some international transport insurance companies place special premiums on the Strait due to perceived “risk”, the vast military presence significantly deters pirate activity.

However, the U.S. military’s activity in the Strait does not sit well with China. From China’s perspective, their geopolitical rival is signaling geopolitical dominance in their lifeline to the world westward. The notable Chinese population in Malaysia, combined with infrastructural investments there, have led to improved Sino-Malaysian relations in recent years, but Singapore has shown to be more stubborn in this respect (despite larger Chinese cultural ties than Malaysia).

Geopolitical Implications

Chinese influence has increased greatly in the area within the past few decades. In the unlikely contingency of war between the U.S. and China, the Strait would be a vital zone of control. If the U.S. had undisputed dominance of it during an armed conflict, then this would pose a great threat to Chinese economic capability. This increases China’s incentive to expand naval operations there, yet not by much. Direct armed conflict between the United States and China is unlikely and is also economically unwise.

The current arrangement provides enhanced protection to trade routes of America and its allies, much of which includes commerce with China. Both the United States and China stand to benefit in this win-win scenario. China is a mass exporter of manufactured goods and a mass importer of oil, with many of their trade partners existing in regions best accessed through the SoM. Most of China’s oil comes from countries like Saudi Arabia and other Gulf States, which are subject to great influence from the United States. The bolstering of economies in this region can easily be seen as a positive outcome from the American point of view.

There is much to ponder in the possibility of armed conflict between China and America in the context of the SoM, yet it is far more pragmatic to ponder peace and economic mutual development. Through a peaceful lens, the situation in the region turns from a contention between American and Chinese influence to one of potential benefit for all parties involved.

The Strait’s Future and its Alternatives

As Chinese trade increases, so does its naval presence. The future is not entirely clear, but most signs point to little change from the current situation. The two hazards mentioned previously will likely be the greatest challenges in the near term. Piracy, assuming it follows its current trend, will fade into being nothing but a rare occurrence. Meanwhile, the three strait-adjacent nations all have clear goals to lessen the haze. As these economies grow and technology develops, more sophisticated methods to mitigate the negative effects of the haze are on the horizon.

China has looked at the congested nature of the Strait and has already taken first steps in securing alternatives. There have been talks in the past of digging a large canal through the Isthmus of Kra in Thailand, however the disastrous ecological implications of this endeavor mean it will likely not happen.

A far more feasible possibility is the construction of an oil pipeline in Thailand to transport the resource quicker and easier to China. China’s constant rate of modern development paired with a limited supply of domestic fuel sources lead to an ever-increasing need for oil, which is what makes this pipeline so attractive. Other regional waterways, such as the Sunda Strait, have been considered and partially acted on as well. Additionally, a novel rail link is being constructed across the Malay Peninsula and is expected to be completed in the near future as part of China’s Belt and Road initiative. This network will not only transport freight, but passengers as well, further integrating Malaysia’s domestic economy. The geopolitical aspect of trade through Southeast Asia may be contentious, but economically, it spells out great potential development.

Adam Greco is an undergraduate student at the University of Florida.

Featured Image: Internal waves between Sumatra and Malaysia (Photo by NASA MODIS Rapid Response team)

Since publishing the article, has China begun any construction projects to widen canals, build pipelines or roads?