By Major Jeff Wong, USMCR

“As the interwar period suggests, wargaming is one of the most effective means available to offer senior leaders a glimpse of future conflict, however incomplete. Wargames offer opportunities to test new ideas and explore the art of the possible. They help us imagine alternative ways of operating and envision new capabilities that might make a difference on future battlefields.”1

– Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert O. Work and General Paul Selva, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, December 8, 2015

Why Wargame?

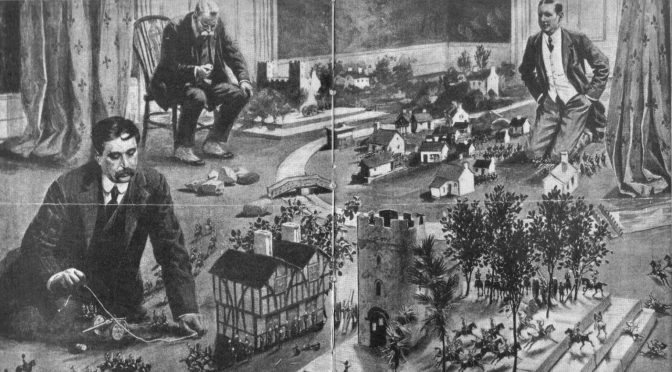

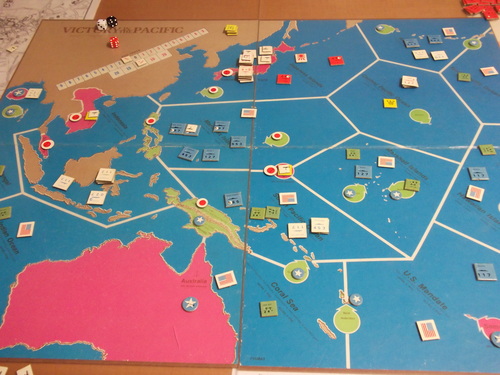

Chester Nimitz fought the Japanese long before they attacked Pearl Harbor. During wargames played at the Naval War College in 1922, the promising commander raced a make-believe fleet thousands of miles across the Pacific Ocean to reinforce the besieged American garrison in the Philippines. Nimitz pushed small icons representing U.S. aircraft carriers, battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and auxiliaries across a large map of the Pacific on the floor of the college’s game room – getting them west but stretching sea lines of communication across the vast ocean. Classmates mimicking Japanese naval doctrine maneuvered their fleet east – isolating the Philippines, seizing U.S. bases, and meeting the American flotilla’s advance. Under the watchful eyes of faculty serving as game umpires, battles ensued. Win or lose, learning occurred without shedding a drop of sailor’s blood or firing a single round. After the Japanese Navy attacked the U.S. Pacific Fleet at anchor in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Nimitz – by then, the commander of the Pacific Fleet – felt ready for the coming conflict. He later wrote, “The war with Japan had been re-enacted in the game rooms at the Naval War College by so many people and in so many different ways that nothing that happened during the war was a surprise” except for the kamikaze.2

Through wargames in Newport – and others played in Tokyo and Berlin – military professionals learned about themselves, their adversaries, and potential solutions to future challenges. When used correctly, wargaming is a relatively inexpensive, yet powerful tool that offers creative solutions to complex problems. When used incorrectly, wargaming confirms poor assumptions, shapes misperceptions, and reinforces hubris. At their best, wargames are vehicles for the pursuit of intellectual honesty and leadership. At their worst, they are barely concealed advocacy platforms that set up false choices for game play to reinforce pre-ordained outcomes.3

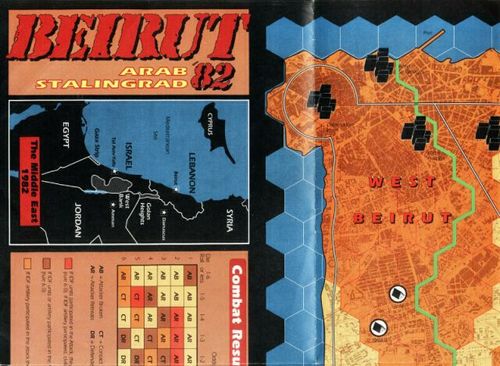

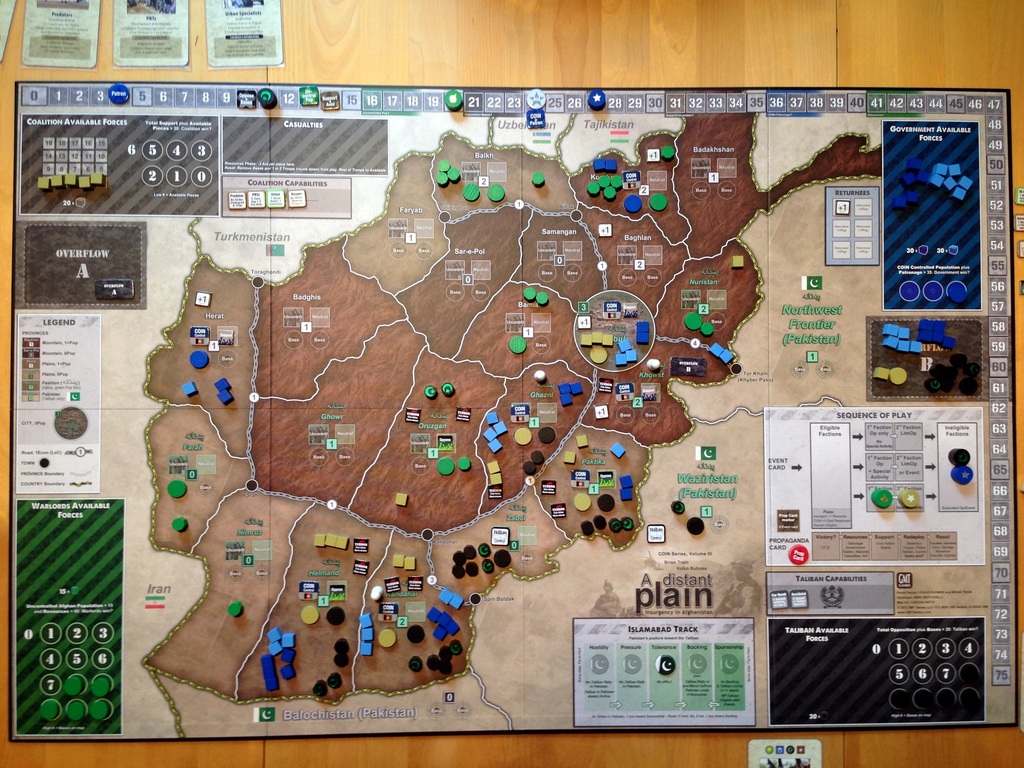

Nevertheless, current senior U.S. defense leaders should look to wargaming’s best practices – particularly German, Japanese, and American games between the First and Second World Wars – to shed light on an uncertain future featuring evolving adversaries, emerging concepts, and untested capabilities. During the period between the First and Second World Wars, wargaming anchored the curricula of professional military education (PME) institutions, allowed commanders and staffs to rehearse and adjust plans for major campaigns, provided a venue for alternate and enemy perspectives, and informed the development of new concepts and capabilities that fed a “cycle of research” to support innovation.4 Today’s U.S. joint force would be wise to apply the best traits of gaming from the interwar-period of the early twentieth century, when wargames blended effectively with the military cultures of Germany, Japan, and the United States to yield insights that affected how they fought during the Second World War.

Military cultures that used wargames reaped their benefits. From the moment the Treaty of Versailles ended the Great War and set the conditions for its successor, senior leaders sought an edge for another global conflict that many observers considered likely.5 In Germany, wargaming expanded its role in the Wehrmacht’s cultural landscape. Officers learned the value of wargames at the famed Kriegsakademie, then applied gaming techniques to develop operational options and explore potential adversary actions during planning for campaigns such as the 1940 invasion of France and the Low Countries. German officers also used wargames to evolve air doctrine and inform aircraft manufacturing decisions that would have serious implications for the Luftwaffe’s strategic-bombing capabilities in the European theater.

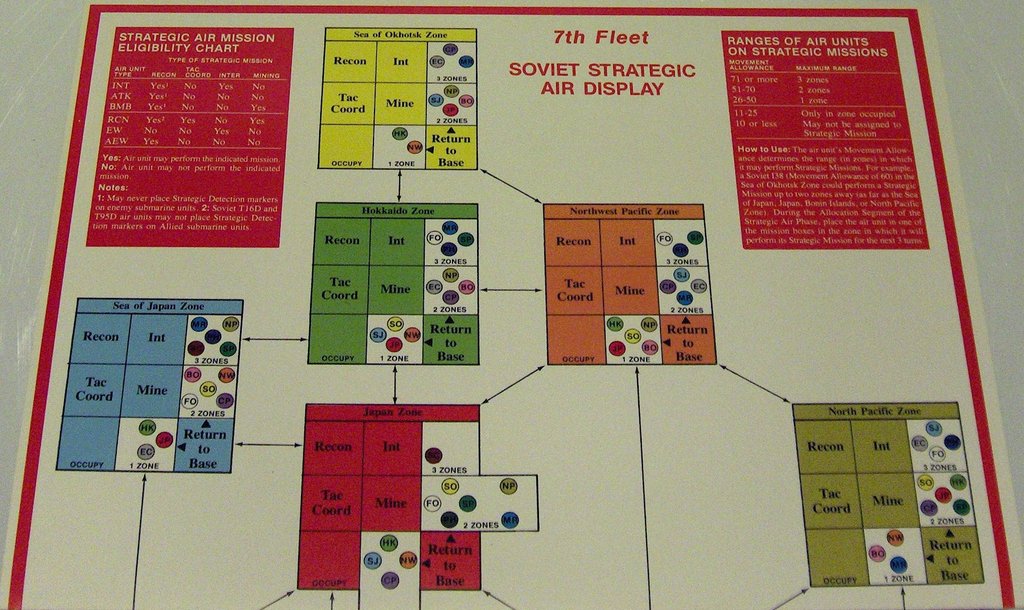

In Japan, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto employed wargames to study the sequencing of his complex Pacific campaign, examine the likely reactions of American and British forces, and allow his subordinate commanders and their staffs to rehearse and adjust plans for major campaigns such as the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor and the strike against the American stronghold on Midway Island. In the United States, American naval officers played hundreds of wargames at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. These games allowed generations of future naval leaders to develop a shared mental model about the strategic and operational framework of the approaching conflict against Japan and provided a venue to test new concepts such as carrier aviation.6 (See Appendix A for information about wargaming and shared mental models). Between 1919 and 1941, German, Japanese, and American wargaming techniques explored new ways of fighting, informed campaign planning, and gave officers decision-making and planning practice before war erupted.

This series of articles will examine interwar-period gaming in three parts. The first part defines wargaming, discusses its utility, and differentiates it from other military analytic tools. The second part details how the militaries of Germany, Japan, and the United States employed wargames to train and educate their officers, plan and execute major campaigns, and inform the development of new concepts and capabilities for the Second World War. The third part concludes by identifying best wargaming practices that can be applied to today’s U.S. defense establishment in order to prepare for future conflicts.

What is a Wargame?

Wargaming must be defined and characterized in order to facilitate substantive discussion. Confusion reigns when military professionals, including senior officers and government civilians, talk about wargaming. Currently, no doctrinal definition for “wargame” or “wargaming” exists.7 The 469-page Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms mentions either term three times, but never actually describes what a wargame is, discusses its traits, or examines its potential utility.8 Professional wargame designers have latched onto variations of a definition established by Dr. Peter Perla, a prominent American wargame designer and longtime research scientist at the Center for Naval Analyses:

“A warfare model or simulation that does not involve the operation of actual forces, in which the flow of events affects and is affected by decisions made during the course of those events by players representing the opposing sides.”9

The military gaming community also acknowledges a similar definition provided by the late Francis J. McHugh, an influential game designer at the U.S. Naval War College:

“A simulation of selected aspects of a military operation in accordance with predetermined rules, data, and procedures to provide decision-making experience or provide decision-making information that is applicable to real-world situations.”10

Wargames are often confused with other problem-solving activities that do not involve the use of actual forces, including course of action (COA) wargaming, tabletop exercises (TTXs), tactical exercises without troops (TEWTs), and rehearsal-of-concept (ROC) drills. COA wargaming is a phase of American and British military planning processes in which options are systematically examined and refined based on enemy capabilities and limitations, potential actions and reactions, and characteristics of the operational environment. During COA wargames, a planning team refines existing options with the help of a so-called “red cell”11 that role-plays and represents the activities of potential adversaries and other factors that could threaten a mission.12 TTXs are scenario-based discussions involving senior officers and staff used to familiarize participants with plans, policies, procedures, and contingencies. TEWTs are commander-led exercises that use current doctrine to exercise subordinate leaders and staff responses against a given threat or scenario on the terrain in which they would fight. ROC drills are detailed rehearsals involving all commanders and staff for a given operation. Although TTXs, TEWTs, and ROC drills are scenario-driven exercises that test decision-making, they lack the “contest of wills,” which is an essential ingredient of wargaming.

Like many tools, wargames hold both great promise and pitfalls. Wargaming is a subjective, people-driven tool that is effective at investigating processes, organizing ideas, exploring issues, explaining implications, and identifying questions for future study.13 In the interwar years, these potential benefits drove military leaders to use wargames to study, question, and understand the plans they had crafted prior to the outbreak of the Second World War. At the same time, wargaming is not an effective tool for calculating outcomes, proving theories, predicting “winners,” producing numbers, and generating conclusions.14

Game designers continually sidestep wargaming’s pitfalls to fulfill their promise. Wargames prove their military utility every time a commander embarks on a mental exercise to rehearse possible solutions to a problem, project an adversary’s response, and assess the decisions made by friend and foe. “It enables a commander and his staff to review assumptions, detect inadequate or untimely support, verify time and space factors, and reconcile divergent opinions,” writes Dr. Williamson Murray. “The game provides a means of testing ideas, of coordinating services and branches, and of exploring and considering all possible contingencies prior to the drafting of the final operational plan.”15 Realistic wargames generate useful insights for subsequent study and live-force exercising when they involve commanders who are experts in the topics being examined, and feature accurate depictions of adversaries and the operational environment.

However, interwar-period gaming experiences also exposed potential problems. German wargames overwhelmingly focused on the operational and tactical implications of its European offensives, but neglected to scrutinize the aggressive strategic guidance that drove its campaigns – and significant operational losses – in Poland and Norway. Japanese wargaming featured a deterministic nature, confirming assumptions senior leaders made before they commissioned the games. American wargames at the Naval War College correctly invested intellectual bandwidth on war in the Pacific and the likely threat – Japan – but overlooked the pivotal 2,073-day Battle of the Atlantic, where German U-boats sank 3,500 Allied merchant ships with 13.5 million tons of shipping bound for the European theater. The Allies lost 175 warships and tens of thousands of merchant and military seamen in the Atlantic.16

Part two will discuss how the militaries of Germany, Japan, and the United States employed wargames to train and educate their officers, plan and execute major campaigns, and inform the development of new concepts and capabilities for the Second World War.

Read Part 2 here.

Major Jeff Wong, USMCR, is a Plans Officer at Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, Plans, Policies and Operations Department. This series is adapted from his USMC Command and Staff College thesis, which finished second place in the 2016 Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Strategic Research Paper Competition. The views expressed in this series are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

Endnotes

1. Robert O. Work and Paul Selva, “Revitalizing Wargaming is Necessary to be Prepared for Future Wars,” War on the Rocks, December 8, 2015 (accessed December 25, 2015). http://warontherocks.com/2015/12/revitalizing-wargaming-is-necessary-to-be-prepared-for-future-wars/.

2. Francis J. McHugh, Fundamentals of War Gaming (Newport, RI: U.S. Naval War College, 1961), 64.

3. Peter Perla (research scientist at the Center for Naval Analyses), interview with Jeff Wong, October 9, 2015.

4. Dr. Peter Perla is credited with first using the term “Cycle of Research” to describe how wargames, exercises, and operations research can mutually support military innovation. Contrast the cycle with the use of the same tools in isolation and independently. Peter Perla, The Art of Wargaming (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1990), 287.

5. Williamson Murray and Allan Reed Millett, A War to be Won: Fighting the Second World War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000), 2.

6. Mental models are psychological representations of real, hypothetical, or imaginary situations. Princeton University, “Mental Models and Reasoning,” (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 2016), accessed February 11, 2016: http://mentalmodels.princeton.edu/about/what-are-mental-models/.

7. Older versions of Joint Publication (JP) 1, Doctrine for the Armed Forces of the United States, defined wargaming as “simulation, by whatever means, of a military operation involving two or more opposing forces, using rules, data, and procedures designed to depict an actual or assumed real-life situation.” Peter Pellegrino, “What is War Gaming?” Lecture at the Naval War College, published December 20, 2012 (accessed December 26, 2015): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=maHpGR-Vj4Q.

8. U.S. Department of Defense, JP 1-02, Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Defense).

9. Perla, The Art of Wargaming, 164.

10. McHugh, Fundamentals of War Gaming, 2.

11. Red “cells” and red “teams” are frequently confused for each other. A red cell is an entity typically led by a staff intelligence officer tasked with representing enemy doctrine and its likely courses of action. A red team is tasked with challenging perceived norms and assumptions made by a commander and his staff in order to improve the validity and quality of a plan.

12. Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, MCDP 5-1, Marine Corps Planning Process (Washington, DC: U.S. Marine Corps, 2011), 1-5.

13. Peter Pellegrino, “What is a War Game?” lecture, U.S. Naval War College, published December 20, 2012 (accessed December 26, 2015).

14. Ibid.

15. Williamson Murray, “Red-Teaming: Its Contribution to Past Military Effectiveness,” DART Working Paper 02-2 (McLean, VA: Hicks and Associates, September 2002), 20-21.

16. Ed Offley, Turning the Tide: How a Small Band of Allied Sailors Defeated the U-boats and Won the Battle of the Atlantic (New York: Basic Books, 2012), 391-92.

Featured Image: NEWPORT, R.I. (May 9, 2013) Lt. Cmdr. Fisher Reynolds, assigned to U.S. Naval War College (NWC) war gaming department, and Brazilian navy Lt. Cmdr. Savio Cavalcanti, from Escola de Guerra Naval, provide inputs to a multi-touch multi-user interface as part of a control group at NWC in Newport, R.I., during the 2013 Inter-American War Game. (U.S. Navy photo by Chief Mass Communication Specialist James E. Foehl/Released)