By Dmitry Filipoff

Losing the Warrior Ethos

“…despite the best efforts of our training teams, our deploying forces were not preparing for the high-end maritime fight and, ultimately, the U.S. Navy’s core mission of sea control.” –Admiral Scott Swift 1

Today, virtually every captain in the U.S. Navy has spent most of his or her career in the post-Cold War era where high-end warfighting skills were de-emphasized. After the Soviet Union fell, there was no navy that could plausibly contest control of the open ocean against the U.S. In taking stock of this new strategic environment, the Navy announced in the major strategy concept document …From the Sea (1992) a “change in focus and, therefore, in priorities for the Naval Service away from operations on the sea toward power projection.”2 This change in focus was toward missions that made the Navy more relevant in campaigns against lower-end threats such as insurgent groups and rogue nations (Iran, Iraq, North Korea, Libya) that were the new focus of national security imperatives. None of these competitors fielded modern navies.

The relatively simplistic missions the U.S. Navy conducted in this power projection era included striking inland targets with missile strikes and airpower, presence through patrolling in forward areas, and security cooperation through partner development engagements. The focus on this skillset has led to an era of complacence where the high-end warfighting skills that were de-emphasized actually atrophied to a significant degree. This possibility was forewarned in another Navy strategy document that sharpened thinking on adapting for a power projection era, Forward…from the Sea (1994): “As we continue to improve our readiness to project power in the littorals, we need to proceed cautiously so as not to jeopardize our readiness for the full spectrum of missions and functions for which we are responsible.”3

Now the strategic environment has changed decisively. Most notably, China is aggressively rising, challenging international norms, and rapidly building a large, modern navy. Because of the predominantly maritime nature of the Pacific theater, the U.S. Navy may prove the most important military service for deterring and winning a major war against this ascendant and destabilizing superpower. If things get to the point where offensive sea control operations are needed and the fleet is gambled in high-end combat, then it is very likely that the associated geopolitical stakes of victory or defeat will be historic. The sudden rise of a powerful maritime rival is coinciding with the atrophy of high-end warfighting skills and the introduction of exceedingly complex technologies, making the recent stunning revelations about how the U.S. Navy has failed to prepare for great power war especially chilling.

Admiral Scott Swift, who leads U.S. Pacific Fleet (the U.S. Navy’s largest and most prioritized operational command), candidly revealed that the Navy was not realistically practicing high-end warfighting skills and operations, including sinking modern enemy fleets, until only two years ago. Ships were not practicing against other ships in the realistic, free-play environments necessary to train and refine tactics and doctrine to win in great power war.

In a recent U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings article, Admiral Swift detailed training and experimentation events occurring in a series of “Fleet Problems.” These events take their name and inspiration from a years-long series of interwar-period fleet experiments and exercises that profoundly influenced how the Navy transformed itself in the run-up to World War Two. While ships practiced against ships in the inter-war period Fleet Problems, the modern version began with the creation of a specialized “Red” team well-versed in wargaming concepts and competitor thinking born from intelligence insights. This Red team is pitched against the Navy’s frontline commanders in Fleet Problem scenarios that simulate high-end warfare through the command of actual warships. What makes their creation an admission of grave institutional failure is that this Red team is leading the first series of realistic high-threat training events at sea in recent memory.

The Navy’s units should be able to practice high-end warfighting skills against one another without the required participation of a highly-specialized Red team adversary to present a meaningful challenge. But Adm. Swift strikingly admits that the Navy’s current system of certifying warfighting skills is not representative of real high-end capability because the Navy “never practiced them together, in combination with multiple tasks, against a free-playing, informed, and representative Red.” Furthermore, “individual commanders rarely if ever [emphasis added] had the opportunity to exercise all these complex operations against a dynamic and thoughtful adversary.”

Core understanding on what makes training realistic and meaningful was absent. Warfighting truths were not being discovered and necessary skills were not being practiced because ships were not facing off against other ships in high-end threat scenarios to test their abilities under realistic conditions. If the nation sent the Navy to fight great power war tomorrow, it would amount to a coach sending a team that “rarely if ever” did practice games to a championship match.

These exercises are not just experiments that push the limits of what is known about modern war at sea. They are also experimental in that they are now figuring out if the U.S. Navy can even do what it has said it could do, including the ability to sink enemy fleets and establish sea control. According to Adm. Swift, the Navy had “never performed” a “critical operational tactic that is used routinely in exercises and assumed to be executable by the fleet [emphasis added]” until it was recently tested in a Fleet Problem. The unsurprising insight: “having never performed the task together at sea, the disconnect” between what the Navy thought it could perform and what it could actually do “never was identified clearly.” Adm. Swift concludes “It was not until we tried to execute under realistic, true free-play conditions that we discovered the problem’s causal factors…” In the Fleet Problems training and experimentation have become one and the same.

Why did the Navy assume it could confidently execute critical operational tactics it had never actually tried in the first place? And if the Navy assumed it could do it, then maybe the rest of the defense establishment and other nations thought so, too. Does this profound disconnect also hold true for foreign and allied navies? Is the unique tactical and doctrinal knowledge being represented by the specialized Red team an admission that competitors are training their units and validating their warfighting concepts through more realistic practice? Even though it is impossible to truly simulate all the chaos of real combat, only now are important ground truths of high-end naval warfare just being discovered which could prompt major reassessments of what the Navy can really contribute in great power war.

The entirety of the train, man, and equip enterprise that produces ready military forces for deployment must be built upon a coherent vision of how real war works. The advent of the Fleet Problems suggests that if one were to ask the Navy’s unit leaders what their real-world vision is of how to fight modern enemy warships as part of a distributed and networked force their responses would have little in common. If great power war breaks out tomorrow, the Navy’s frontline commanders could be forced to improvise warfighting fundamentals from the very beginning. Simple lessons would be learned at great cost in blood and treasure.

Many of the major revelations coming from the Fleet Problems are not unique innovations, but rather symptoms of deep neglect for a core element of preparing for war – pitting real-life units against one another to test people, ideas, and technology under realistic conditions. Adm. Swift surprisingly describes using a Red team to connect intelligence insights, wargaming concepts, training, and real-life experimentation as “new ground.” Swift also noted that as the Navy attempted its purported concepts of operations in the Fleet Problems “it became apparent there were warfighting tasks that were critical to success that we could not execute with confidence.” In a normal context, it would not always be noteworthy for a military to invalidate concepts or realize it can’t do something well. What makes these statements revelations is that the process of testing concepts and people in realistic conditions simulating great power war has only just begun.

This is a failure with profound implications. The insight that comes from training and experimenting against realistic threats forms a critical foundation for the rest of the military enterprise. Realistic experimentation and training is indispensable for developing meaningful doctrine, tactics, and operational art. Much of the advanced concept development on great power war by the Navy hasn’t been validated by real-world testing. The creation of the new Fleet Problems is fundamentally an admission that not only is the Navy unsure of its ability to execute core missions, but that major decisions about its future development were built on flaws. While the Fleet Problems are finally injecting much needed realism into the Navy’s thinking, their creation reveals that the entire defense establishment has suffered a major disconnect from the real character of modern naval warfare. The Fleet Problems have likely invalidated years of planning and numerous basic assumptions.

The Navy must now account for how many years it did not practice its forces in meaningful, high-end threat training in order to understand just how widespread this lack of realistic experience has penetrated its ranks. There should be no doubt that this has skewed decision-making at senior levels of leadership. How many leaders making important decisions about capability development, training, and requirements have zero firsthand experience commanding forces in high-end threat training? Could the fleet commanders operate networked and distributed formations if war breaks out? Has best military advice on the value of naval power for the nation’s national security interests been predicated on untested warfighting assumptions?

To Train the Fleet for What?

“The department directs that a board of officers, qualified by experience, be ordered to prepare a manual of torpedo tactics which will be submitted by the department to the War College, and after such discussion and revision as may be necessary, will be printed and issued to the torpedo officers of the service for trial. This order has not been complied with. If it had been, it would doubtless have resulted in a sort of tentative doctrine which, though it might well have been better than the flotilla’s first attempt, could not have been as complete or as reliable as one developed through progressive trials at sea; and it might well have contained very dangerous mistakes.”–William S. Sims 4

Adm. Swift reveals that it was even debated whether free-play elements should play a role at all in certifying units to be combat ready: “there was concern in some circles that adding free-play elements to the limited time in the training schedule would come at the cost of unit certification. Others contended it was unrealistic and unfair to ask units that were not yet certified to perform our most difficult warfighting tasks.” The degree of certification is moot. Sailors are failing anyway because the shift in warfighting focus toward great power competition has not been matched by new training standards and therefore not penetrated down to the unit level.

Adm. Swift notes startling lessons: “In some scenarios, we learned that the ‘by the book’ procedure can place a strike group at risk simply because our standard operating procedures were written without considering a high-end wartime environment.” This is a direct result of the change in focus toward power projection missions against threats without modern navies. According to Adm. Swift the regular exercise schedule consisted of missions including “maritime interdiction operations, strait transits, and air wings focused on power projection from sanctuary” which meant that forces were “not preparing for the high-end maritime fight and, ultimately, the U.S. Navy’s core mission of sea control.” In this new context of a high-end fight in a Fleet Problem, according to Adm. Swift, “If we presented an accurate—which is to say hard—problem, there was a high probability the forces involved were going to fail. In our regular training events, that simply does not happen at the rate we assess will occur in war.” The Fleet Problems are revealing that Navy units are not able to confidently execute high-end warfighting operations regardless of the state of their training certifications.

These revelations demonstrate that the way the Navy certifies its units as ready for war is broken. A profound disconnect exists between the Navy’s certification and training processes for various warfighting skills and what is actually required in war. Entire sets of training certifications and standard operating procedures born of the post-Cold War era are inadequate for gauging the Navy’s ability to fight great power conflict.

Mentally Absent in the Midst of the Largest Technological Revolution

“The American navy in particular has been fascinated with hardware, esteems technical competence, and is prone to solve its tactical deficiencies with engineering improvements. Indeed, there are officers in peacetime who regard the official statement of a requirement for a new piece of hardware as the end of their responsibility in correcting a current operational deficiency. This is a trap.” Capt. Wayne P. Hughes, Jr. (Ret.) 5

Regardless of a major shift in national security priorities toward lower-end threats, the astonishing pace of technological change constitutes an extremely volatile factor in the strategic environment that needs to be constantly paced by realistic training and experimentation under free-play conditions. The modern technological foundation upon which to devise tactics and doctrine is built on sand.

The advent of the information age has unlocked an unprecedented degree of flexibility for the conduct of naval warfare as platforms and payloads can be connected in real-time in numerous ways across great distances. This has resulted in a military-technical revolution as marked as when iron and steam combined to overtake wooden ships of sail. A single modern destroyer fully loaded with network-enabled anti-ship missiles has enough firepower to singlehandedly sink the entirety of the U.S. Navy’s WWII battleship and fleet carrier force.6 On the flipside, another modern destroyer could field the defensive capability to stop that same missile salvo.

Warfighting fundamentals are being reappraised in an information-focused context. The process by which forces find, target, and engage their opponents, known as the kill chain, is enabled by information at each individual step of the sequence. A key obstacle is meeting that burden of information in order to advance to the next step. This challenge is exacerbated by the great distances of open-ocean warfare and the difficulty of getting timely information to where it needs to be while the adversary seeks to deceive and degrade the network. Technological advancement means the kill chain’s information burdens can be increasingly met and interfered with.

The threshold of information needed for the archer to shoot decreases the smarter the arrow gets. Information-age advancements have therefore wildly increased the power of the most destructive conventional weapon ever put to sea, the autonomous salvo of swarming anti-ship missiles.

The next iteration of these missiles will have a robust suite of onboard sensors, datalinks, jamming capability, and artificial intelligence. These capabilities will combine to build resilience into the kill chain by containing as much of that process as possible within the missile itself. More and more of the need for the most up-to-date information will be met by the missile swarm’s own sensors and decided upon by its artificial intelligence. Once fired, these missiles are on a one-way trip, allowing them to discard survivability for the sake of seizing more opportunities to collect and pass information. Unlike most other information-gaining assets, these missiles will be able to close with potential targets to resolve lingering concerns of deception and identification. The missile’s infrared and electro-optical capabilities in particular will provide undetectable, jam-resistant sensors for final identification that will prove challenging to deceive with countermeasures. On final approach, the missile will pick a precise point on the ship to guarantee a kill, such as where ammunition is stored.

The most fierce enemy in naval warfare has taken the form of autonomous networked missile salvos where the Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act (OODA) decision cycle will be transpiring within the swarm at machine speeds. Is the Navy ready to use and defend against these decisive weapons?

The Navy may feel inclined to say yes to the latter question sooner because shooting things out of the sky has been a special focus of the Surface Navy and naval aviation since WWII. The latest technology that will take this capability into the 21st century, the Naval Integrated Fire Control – Counter-Air (NIFC-CA) networking capability, will help unite the sensors and weapons of the Navy’s ships and aircraft. Aircraft will be able to use a warship’s missiles to shoot down threats the ship can’t see itself. This is decisive because anti-ship missiles will make their final approach at low altitudes below the horizon where they can’t be detected by a ship’s radar. Modern warships can be forced to wait until the final seconds to bring most of their defensive firepower to bear on a supersonic inbound missile salvo unless a networked aircraft can cue their fires with accurate sensor information from high above.

This makes mastering NIFC-CA perhaps the most important defensive capability the fleet needs to train for, but this will involve a steep learning curve. Speaking on the challenges of making this capability a reality, then-Captain Jim Kilby remarked that it involves “a level of coordination we’ve never had to execute before and a level of integration between aircrews and ship crews.”7 Is the Navy truly practicing and refining this capability in realistic environments? At least three years before the Fleet Problems started, the Chief of Naval Operations reported that concepts of operation were established for NIFC-CA.8

There should be little confidence that naval forces have a deep comprehension of how information has revolutionized naval warfare and how modern fleet combat will play out because there was a lapse in necessary realistic experimentation at sea. The way the Navy thought it would operate may not actually make sense in war, a key insight that experimentation will reveal as it did in the interwar period.

Training and Experimentation for Now and Tomorrow

“If…the present system fails to anticipate and to adequately provide for the conditions to be expected during hostilities of such nature, it is obviously imperative that it be modified; wholly regardless of the effect of such change upon administration or upon the outcome of any peace activity whatsoever.” –Dudley W. Knox 9

The extent to which the Navy’s current capabilities have been tested by meaningful real-world training and experimentation is now in doubt. This doubt naturally extends to things that the Navy has just fielded or is about to introduce to the fleet. Yet Adm. Swift revealed a fatal flaw in the Fleet Problems that is not in keeping with a high-velocity learning or warfighting-first mindset: “We are not notionally employing systems and weapons that are not already deployed in the fleet. Each unit attacks the problem using what it has on hand (physically and intellectually) today.”

It is a mistake to not train forces to use future weapons. Units must absolutely attempt to experiment with capabilities not yet in the fleet to stay ahead of the ever-quickening pace of change. Realism should be occasionally sacrificed to anticipate the basic parameters of capabilities that are about to be fielded. Sailors should be thinking about how to employ advanced anti-ship missiles about to hit the fleet that feature hundreds of miles of range like the Long Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM), Standard Missile 6, and the Maritime Strike Tomahawk. These capabilities are far more versatile than the Navy’s only current ship-to-ship missile, the very short-range and antiquated Harpoon missile the Navy first fielded over 40 years ago and can’t even carry in its launch cells. Getting sailors to think about weapons before their introduction will mentally prepare them for new capabilities and warfighting realities.

Information-enabled capabilities have come to dominate every facet of offense, defense, and decision. Do naval aviators know how to retarget friendly salvos of networked missiles amidst a mass of deception and defensive counter-air capabilities while leveraging warship capabilities to target enemy missile salvos simultaneously? Do fleet commanders know how to maneuver numerous aerial network nodes to fuse sensors and establish flows of critical information that react to emerging threats and opportunities? Can commanders effectively manage and verify enormous amounts of information while the defense establishment and industrial base are being aggressively hacked by a great power? According to the Navy’s current service strategy document, A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower, warfare concept development should involve efforts to “…re-align Navy training, tactics development, operational support, and assessments with our warfare mission areas to mirror how we currently organize to fight.” 10

Despite all the enormous effort and long wait times that accompany the introduction of a new system, the Fleet Problems remind the defense establishment that the Navy can’t be expected to know how to use it simply because it is fielded. New warfighting certifications are in order and must be rapidly redefined and benchmarked by the Fleet Problems in order to pace technology and make the Navy credible. This will require that a significant amount of time be dedicated to real-world experimentation.

So How the Does the Navy Spend its Time?

“Our forward presence force is the finest such force in the world. But operational effectiveness in the wrong competitive space may not lead to mission success. More fundamentally, has the underlying rule set changed so that we are now in a different competitive space? How will we revalue the attributes in our organization?” –Vice Admiral Arthur K. Cebrowski and John J. Garstka 11

These severe experimentation and training shortfalls are not at all due to lack of funding, but rather by faulty decisions on what is actually important for Sailors to focus their time on and what naval forces should be used for in the absence of great power war. Meanwhile, the power projection era featured extreme deployment rates that have run the Navy into the ground.

The Government Accountability Office states that 63 percent of the Navy’s destroyers, 83 percent of its submarines, and 86 percent of its aircraft carriers experienced maintenance overruns from FY 2011-2016 that resulted in almost 14,000 lost operational days – days where ships were not available for operations.12 How much of this monumental deployment effort went toward aggressively experimenting and training for great power conflict instead of performing lower-end missions? Hardly any if none at all because Adm. Swift termed the idea to use a unit’s deployment time for realistic experimentation an “epiphany.”

In order to more efficiently meet insatiable operational demand and slow the rate of material degradation the Navy implemented the Optimized Fleet Response Plan (OFRP) that reforms the cycle by which the Navy generates ready forces through maintenance, training, and sustainment phases.13 But Adm. Swift alleges that this major reform has caused the Navy to improperly invest its time:

“Commanders were busy following the core elements in our Optimized Fleet Response Plan (OFRP) training model, going from event to event and working their way through the list of training objectives as efficiently as possible. Rarely did we create an environment that allowed them to move beyond the restraints of efficiency to the warfighting training mandate to ensure the effectiveness of tactics, techniques, and procedures. We were not creating an environment for them to develop their own warfighting creativity and initiative.”

A check-in-the-box culture has been instituted to cope with crushing deployments rates at the expense of fostering leaders that embody the true warfighter ethos of imaginative tacticians and operational commanders. The OFRP cycle is under so much tension from insatiable demand and run-down equipment that Adm. Swift described it as a “Swiss watch—touching any part tended to cause the interlocking elements to bind, to the detriment of the training audience.” But as Adm. Swift already noted, pre-deployment training wasn’t even focused on preparing for the high-end fight anyway.

Every single deployment is an opportunity to practice and experiment. Simply teaching unit leaders to make time for such events will be valuable training itself as they figure out how to delegate responsibilities in an environment that more closely approximates wartime conditions. After all, if units are currently straining on 30 hours of sleep a week performing low-end missions and administrative tasks, how can we be sure they know how to make time to fight a high-stakes war while also maintaining a ship that’s falling apart?

Being a deckplate leader of a warship has always been an enormously busy job and there is always something a warship can do to be relevant. But it is a core competence of leaders at all levels to know what to make time for and how to delegate accordingly. From the sailor checking maintenance tasks to the combatant commander tasking ships for partner development engagements, a top-to-bottom reappraisal of what the Navy needs to spend its time doing is in order. Are Sailors performing tasks really needed to win a war? Are the ships being deployed on missions that serve meaningful priorities?

Major reform will be necessary in order to reestablish priorities to make large amounts of time for realistic training and experimentation. In addition to making enough time, it is also a question of having enough forces on hand when the fleet is stretched thin. Adm. Swift described a carrier strike group (CSG) being used in a Fleet Problem where “the entire CSG was OpFor [Red team] – an enormous investment that yielded unique and valuable lessons.” Does this mean that aircraft carriers, the Navy’s largest and most expensive warships, are especially hard-pressed to secure time for realistic experimentation and training? Can the Navy assemble more than a strike group’s worth of ships to simulate a competitor’s naval forces?

The recent deployment of three strike groups to the Pacific means it is possible. Basic considerations include asking whether the Navy has enough ships on hand to simulate a distributed fleet and enough units to simulate great power adversaries that have the advantages of time, space, and numbers. But with where the deployment priorities currently stand, the Navy may not have enough time or ships on hand to regularly simulate accurate scenarios.

A Credibility Crisis in the Making

“…there are many, many examples of where our ships – their commanding officers, their crews are doing very well, but if it’s not monitored on a continuous basis these skills can atrophy very quickly.” – Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson 14

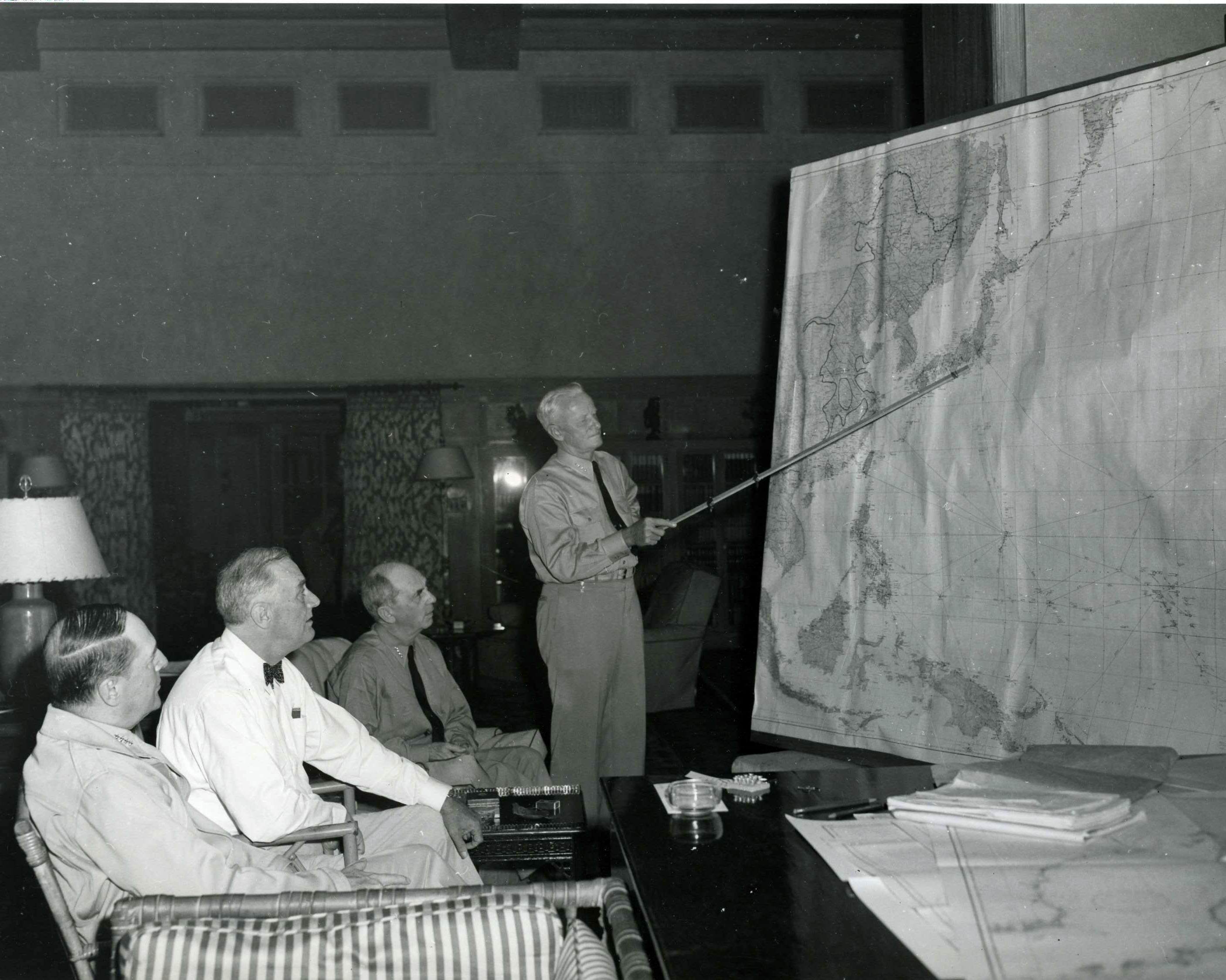

When great power conflict last broke out in WWII the war at sea was won by admirals like Ernest King, Chester Nimitz, and Raymond Spruance whose formative career experiences were greatly influenced by the interwar-period Fleet Problems. This tradition of excellence based on realism is in doubt today.

What is clear is that business as usual cannot go on. The fundamental necessity of free-play elements for ensuring warfighting realism is beyond reproach. The reemergence of competition between the world’s greatest powers in a maritime theater is making many of the Navy’s power projection skillsets less and less relevant to geopolitical reality. New deployment priorities must preference realistic training and experimentation to make up for lost ground in concept development, accurately inform planning, understand the true limits and potential of technology, and test the mettle of frontline units.

The recent pair of collisions challenged numerous assumptions about how the Navy operates and how it maintains its competencies. Tragic as those events were, they thankfully stimulated an energetic atmosphere of reflection and reform. But the competencies that such reforms are targeting include things like navigation, seamanship, and ship-handling. These basic maritime skills have existed for thousands of years. What is far newer, endlessly more complex, and absolutely vital to deter and win wars is the ability to employ networked and distributed naval forces in great power conflict. Compared to the fatal collisions, countless more sailors are dying virtual deaths in the Fleet Problems that are revealing shocking deficiencies in how the Navy prepares for war. Short of horrifying losses in real combat, there is no greater wake-up call.

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content. Contact him at Nextwar@cimsec.org.

References

[1] Admiral Scott H. Swift, “Fleet Problems Offer Opportunities” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, March 2018. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2018-03/fleet-problems-offer-opportunities

[2] Forward…From the Sea, U.S. Department of the Navy, 1994. https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/policy/navy/forward-from-the-sea.pdf

[3] Ibid., 8.

[4] William S. Sims, “Naval War College Principles and Methods Applied Afloat” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, March-April 1915. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1915-03/naval-war-college-principles-and-methods-applied-afloat

[5] Wayne P. Hughes, Jr., Fleet Tactics: Theory and Practice, Second Edition, pg. 33, Naval Institute Press, 1999.

[6] Can be inferred from official U.S. Navy ship counts on battleships and aircraft carriers and near-term capabilities of anti-ship capabilities.

[7] Sam LaGrone, “The Next Act for Aegis”, U.S. Naval Institute News, May 7, 2014. https://news.usni.org/2014/05/07/next-act-aegis

[8] CNO’s Position Report 2013, U.S. Department of the Navy. http://www.navy.mil/cno/131121_PositionReport.pdf

[9] Dudley W. Knox, “The Role of Doctrine in Naval Warfare.” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, March-April 1915. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1915-03/role-doctrine-naval-warfare

[10] A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower. http://www.navy.mil/local/maritime/150227-CS21R-Final.pdf

[11] Vice Admiral Arthur K. Cebrowski and John J. Garstka, “Network Centric Warfare: It’s Origin, It’s Future.” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, January 1998. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1998-01/network-centric-warfare-its-origin-and-future

[12] John H Pendleton, “Testimony Before the Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate Navy Readiness: Actions Needed to Address Persistent Maintenance, Training, and Other Challenges Affecting the Fleet. Government Accountability Office, September 19, 2017. https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/687224.pdf

[13] “What is the Optimized Fleet Response Plan and What Will It Accomplish?” U.S. Fleet Forces Command, Navy Live, January 15, 2014. http://navylive.dodlive.mil/2014/01/15/what-is-the-optimized-fleet-response-plan-and-what-will-it-accomplish/

[14] Department of Defense Press Briefing by Adm. Richardson on results of the Fleet Comprehensive Review and investigations into the collisions involving USS Fitzgerald and USS John S. McCain, November 2, 2017. https://www.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript-View/Article/1361655/department-of-defense-press-briefing-by-adm-richardson-on-results-of-the-fleet/

Featured Image: SASEBO, Japan (Feb. 28, 2018) Operations Specialist 2nd Class Megann Helton practices course plotting during a fast cruise onboard the amphibious assault ship USS Wasp (LHD 1). (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Levingston Lewis/Released)