By Christopher Nelson

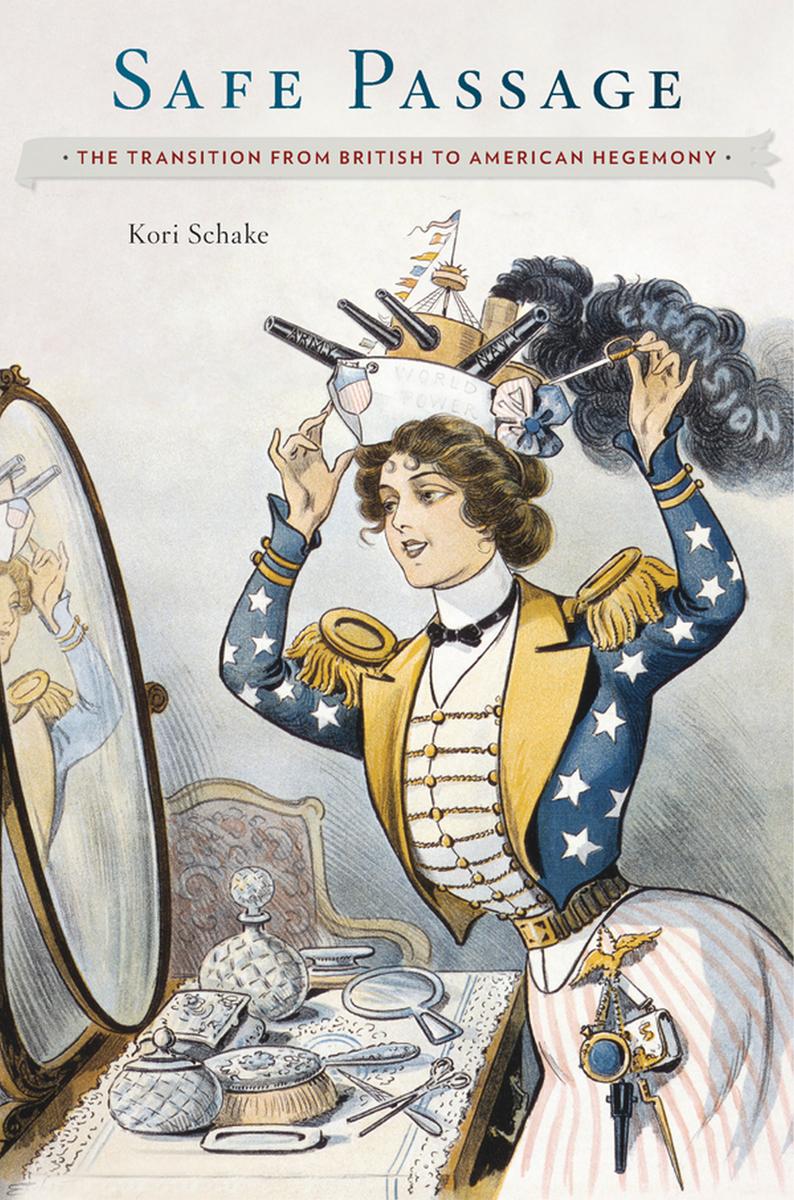

Recently I had the chance to talk to Dr. Kori Schake about her new book, Safe Passage: From British to American Hegemony. Her book describes the only case of a peaceful hegemonic transition between two nations. In this instance, it was the gradual transition from British to American hegemony beginning in the 19th century and ending at the end of World War II with America firm ly situated as the global leader.

ly situated as the global leader.

We spoke for over an hour about her book, history, the great Tom Schelling, and of course, what she’s reading these days. It was a fun and fascinating discussion. I hope you enjoy it as much as I did.

Christopher Nelson: Professor Schake, thank you so much for taking the time to chat. Before we get into details of the book, I want to start by asking you about the book’s cover. It’s a fabulous picture and I got to say, it stands out in the sea of books on international relations and national security. Having listened to you speak on a panel before – full of energy and jazz – I’ll admit that the picture reminds me of a 19th century Kori Schake. Did you discover it? Your editor? Where’s it from?

Kori Schake: [Laughter] Yes! It’s a 19th century portrait of me! You are exactly right. I did pick it. I found it when I was doing the research for the book. And I love the way it’s what we look like to Britain when America was a rising power: she’s confidently assessing her appearance in the mirror, adjusting a battleship hat, and the accoutrements of war are literally hanging off her purse strings.

Nelson: I’m a big believer that a book’s dedication is important. Quickly skipped by many, but important. You dedicated this book to Tom Schelling. Many readers will recognize his name and have read his work, some have not. I discovered Arms and Influence much too late in my naval career. It’s fantastic. Who was he, but more important, how did he mentor you as an academic, as a thinker, as a student?

Schake: I was so lucky to have the privilege of learning from Tom. He was not at the University of Maryland when I went there to do my graduate work. But he came there and he was such a warm, fostering, generous soul. It was such a privilege to learn from him. But I have to tell you, Tom Schelling gave me some of the best advice about life.

He rushed me through my PhD dissertation because I had been A.D.D for six years. I was a year into my dissertation research when I got a posh fellowship to go work as a civilian in General Powell’s Joint Staff in the summer of 1990. This was two weeks after Iraq invaded Kuwait. I went off to work with General Powell for a year and stayed in the Pentagon for six years. And Tom, bless his heart, kept writing letters to the chancellor of the university who was understandably trying to clear me off the rolls of the PhD program because it was so obvious I was never going to finish. Tom kept writing these beautiful letters saying, “She’s not working in a shoe store, she’s doing the kind of jobs we would want someone who held a PhD from this institution to be doing.” So he kept them from throwing me out.

When I left the Pentagon I wrote my PhD dissertation in six months. It’s terrible. What Tom kept saying was, “Get the dissertation done and make the book perfect.” He understood what a flight risk I was. And so I am living proof that if the minimum wasn’t good enough it would not be the minimum. I got my dissertation done and went on doing work that I liked and wanted to do.

Tom eventually brought me back to Maryland for my first teaching job. There is never going to be a better day in my professional life than the day of my PhD defense. At the end of it Tom thanked me for teaching him something about strategy.

Nelson: What did you teach him?

Schake: I didn’t teach him anything. It’s proof of what a gentleman he was. I wrote my dissertation on strategy and the Berlin Crisis in 1958 and 1961. I did not realize when I chose the topic that Tom had been an advisor to the Kennedy administration in 1961. The conclusion of my dissertation was that the Kennedy administration had actually made a delicate situation much worse by treating the crisis as a problem about the risk of war with the Soviet Union rather than treating it as a problem of how to keep Germany voluntarily allied with the West. So I ended up being very critical of the policy choices the administration he was advising had come to. He could not have been happier [Laughter]. He said it was wonderful that I thought for myself on the subject and agreed with me in retrospect. The frame of reference that the Kennedy administration put on the problem led to worse solutions than the policies the Eisenhower administration had taken.

Nelson: How did the idea come about to write the book? What is it about the transition between British and U.S. global hegemony that interests you?

Schake: The idea was germinating for a long time. With all of the talk of the rise of China and whether it can happen peacefully and what it means for the U.S., I kept wondering: What are the precedents? What worked last time and what didn’t? I didn’t even know enough about the subject when I started writing to realize that there was only one peaceful hegemonic transition in history. I thought I was going to be looking at whole bunch of case studies. And when I started doing the research for the book I realized I couldn’t write it as a political science book because there are no case studies. There is a single case study if you’re looking at peaceful transition.

Nelson: So what would a statistician say?

Schake: If N=1 you can never draw a conclusion, that’s what a statistician would say. But history does not give us the luxury of an N sufficiently large to draw a robust conclusion. History gives us what it gives us.

If, for example, you read Graham Allison’s book on the rise of China, what Graham tries to do was force the problem into a political science framework by expanding the definition of hegemonic transition to get more than one case of a peaceful transfer. And I think that is much more problematic. For example, one case of hegemonic transition he uses is the shift of power from Britain and France after World War II towards Germany. But of course all three of those countries have the same security guarantor.

So first of all, it’s not a hegemonic transition. There was a hegemon setting the rules. And second of all, it wasn’t a hegemonic transition because we imposed the rules on our three close allies because we were worried about an entirely different problem.

I thought about the question of hegemonic transition a long time – years in fact. I kept worrying that somebody smarter than me was going to write this book before I got to it. I watched the book review section with enormous trepidation that someone like Aaron Friedberg would have turned his attention to this or anyone of the dozens and dozens of people who could do a better job than I did in the writing of this. But nobody got to it before I got to it!

As you know, Chris, I’m not a historian of the 19th century. But I got obsessed with this question of peaceful hegemonic transition and I had to learn the history of the 19th century in order to answer the question I was interested in. My other big worry was that historians were going to point out that I wasn’t part of the tribe. You know, the thirty-seven things I ought to have understood about this period of time that anybody knowledgeable on the subject would know but I didn’t’ know – I kept waiting in agony that that would be the verdict. I feel like I got away with the jailbreak of the century, but so far the reviews have been good.

Nelson: Fascinating. How does this fit with the idea that there’s a list of smart, well-read, popular writers out there that are writing about topics as non-professionals, in the sense they may not have an advanced degree in the specific subject – and here I’m thinking of people like Malcolm Gladwell, Nicholas Taleb, David McCullough and many more – but they are able to connect different ideas, sometimes across different disciplines, and convey them very well.

Schake: I hate reading history where somebody avalanches everything they know on a subject at me; historians are curators, that’s what they do. I want someone to tell me what is relevant and interesting about a particular problem. As General Powell used to tease me all the time when I worked at the Joint Staff that there were lots of reasons to fire me but there were two reasons not to. The first reason not to fire me was that it was kind of funny to watch me do my job. And the second was because I was the only NATO expert he ever met that when he asked what time it was, I would just tell him what time it was [Laughter]. Yes. I wouldn’t start with first the earth cooled, and then sun-dials, and then clocks…

But back to your question, they ask interesting questions and then they tell a story. They’re engaging storytellers which is what every good teacher is.

Nelson: How do you research and write? For instance, are you a longhand writer that finds a few hours every morning to write and then transcribe it to a computer? What’s your process?

Schake: I basically break it down into three stages.

The first stage is just thinking about what’s the right question. What’s the right question that unlocks understanding about an important subject? Many books that I’m bored reading are books that are about a subject, not about a question. I try to always discipline myself to think about issues in terms of what is the right question because then I can figure out what does it take to answer the question.

For me the second stage is trying to figure out what would prove the answer right and what would prove it wrong? What is the discriminating data that would help me figure out if I have the right answer or not. I’m extremely Germanic in my approach to writing. The architecture actually matters to me because I find that I’m a poor editor of my own work. Once I write it it’s hard for me to throw it all away, so unless I’m disciplined enough to structure it in ways that are not just driving down a rabbit hole, I need to understand this to explain this, and here’s the place to talk about this, that sort of thing. Unless I force myself into the discipline of structure I just walk around the house in my pajamas talking to myself and it doesn’t end up being something that is valuable to anyone.

The last third of it is the actual writing of it.

Nelson: So you’re the person who has to do the outline with pen and paper?

Schake: Yes. When I’m researching I start building blocks of research. As I look at flows of bits of information I am trying to figure out how to tell the story. I outline the book, the details are outlined, the research is plugged into the outline, and then I write to stitch the pieces together. It’s unimaginative and Germanic. But unless I do that I’m way too self-indulgent and I end up with a lot of stuff that will end up on the editing floor.

Nelson: Throughout the book you introduce different international relation perspectives when you outline how historians, political scientists, and others have tried to describe the relationship between the U.S. and Britain during this period of transition. In the international relations field, what do you consider yourself? Simply, what’s your worldview? Are you a Realist?

Schake: I am badly trained in several disciplines.

Nelson: [Laughter]

Schake: No, that is the honest to god truth, Chris. My degrees are in political science, yet I write history and I was trained by an economist.

Nelson: [Laugh] That’s a lovely dodge. But seriously, I’m curious, what’s Kori Schake’s worldview?

Schake: I had the privilege of being with an extraordinary group of people a few months ago in something called the Civic Collaboratory. It’s run by an outstanding American by the name of Eric Liu who is dedicated to rebuilding the bonds of affection and cooperation among Americans.

The Collaboratory is something where everybody who goes is the head of an organization in the public sphere, for example, one person is the head of the 92nd Street Y in New York City. Eric uses a diverse group of people, some of whom will pitch the next idea for what they are working on. Everybody else in the group tries to come up with ways to help. It can be big, it can be little, but the point is to try to help each other.

One of the most inspiring people I met in this amazing group of people was a woman who was teaching history. She told me the motto of her organization. It is now the motto of my worldview, which is this: people make choices, and choices make history. For me that really is how I think about it. I don’t believe in immutable forces of history like the crushing burden of economic determinism, or religious determinism, or political determinism. I think we have wide latitude to craft our fate and so I think the only thing that the Realists have right when talking about American foreign policy is that they were incredibly smart to choose the best name. Because if you’re the realist everybody else is unrealistic.

Also, the Realist description of how governments make choices don’t correlate with what I think of America in the 20th century. For me, the most powerful thing I learned when writing Safe Passage was that as the United States grew more powerful it grew more liberal. We reversed the trend that governed every other powerful state, which is as other countries became more powerful they bent the rules to their advantage. In contrast, when we became more powerful we gave wider latitude to others to affect our choices and legitimatize our power. That really does make America in the time of its hegemony unique. As an American I found it incredibly touching.

Nelson: Your book details nine historic moments between the U.S. and Britain, from 1823 to 1923, that you use to illustrate as pivotal points towards hegemonic transition – but it wasn’t smooth. What were some of the more significant points of friction between the U.S. and Britain during this time that could have led to conflict?

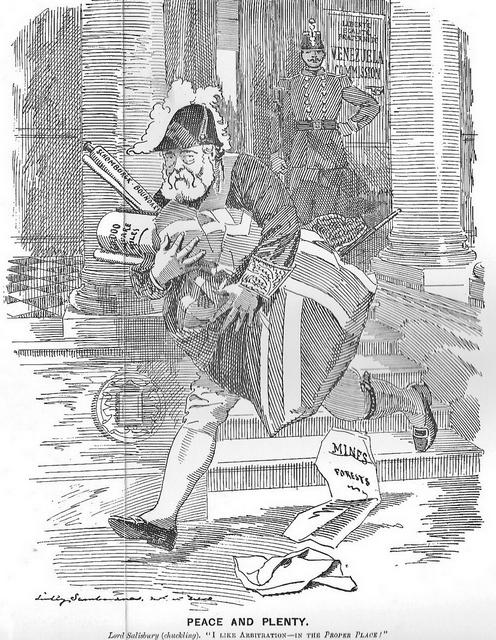

Schake: I love that question, especially because the answer is so obscure. The moment at which things were likely to result in war between Great Britain and the U.S. was the 1895 Venezuelan debt crisis – which nobody knows anything about, it’s lost to history. It’s the moment when war was likeliest, when a rising U.S. was breathtakingly reckless.

The basic story goes like this: Venezuela and Great Britain had been disputing the boundary line along the Orinoco river (which is in Venezuela) for 45 years or so. It becomes a crisis because the British get greedy, the Venezuelan cadillo defaults on loans that for British companies build infrastructure. As an aside it is important to understand that in judging the Venezuelan choices in this, they are only rudimentarily a state at this point. The quality of government is very poor. The British get predatory and they want the mouths of the Orinoco river in return for Venezuela defaulting on their debt. And again, none of this matters to us, except for the fact that the Monroe Doctrine had been American policy for over 70 years and the Venezuelan government had an American lobbyist working for them that wrote op-eds in newspapers all over the U.S. drawing attention to this issue.

Grover Cleveland who was the President at the time was so opposed to imperialism that he refused to proceed with the accession of Hawaii as an American territory. He considered the Monroe Doctrine troublesome. Yet this American lobbyist working for the Venezuelans forced it onto the political agenda by challenging that Cleveland was failing to enforce the Monroe Doctrine. Grover Cleveland, who runs a cabinet-style presidency where he exercised loose control, allows the American Secretary of State to write a 12,000 word demarche to the British that concludes that American law is fiat on this continent. The British don’t even respond to such a ridiculous proposition. Grover Cleveland is then offended that we aren’t being treated more respectfully because we’re a rising power. So he starts to get more engaged and he defends the Secretary of State.

The British reply after another round of this, and they say that they control more territory on the North American Continent than we do – which adds insult to injury. Cleveland then does what every good American President does in foreign policy: he appeals to the recklessness of the American Congress. He gets an unanimous endorsement from Congress to go to war with Great Britain!

Great Britain was the dominant military force in the world at that time. The American Navy’s Caribbean squadron was six ships – and yet we were ready to fight the hegemon of the international order. The British flipped on the issue. In the space of six months they go from derision to Prime Minister Salisbury being cheered in the House of Commons when he announced that there is no greater supporter of the Monroe Doctrine than her majesty’s government. It’s a wonderful case study because why did it change? I found it a very poignant story because civil society in these two democracies is what changed their positions. The United States was an illiberal democracy in the 19th century. Britain wasn’t a democracy but had a more liberal government than most in the international order at the time.

What happens is civil societies reach across cultures. 354 members of the British Parliament write an open letter to the U.S. Congress encouraging peaceful arbitration to resolve the dispute between their countries. American newspapers initiate a write in campaign. The Prince of Wales – the husband of Queen Victoria – writes one of the letters suggesting that war between our two countries is fratricide. That sentimental connection, the sense of being the same, creates space for political compromise that avoids the war.

Nelson: Along that point, when you studied this through an entire century, when was there, as a culture, a sense of collective self-consciousness about the transition? Did the leaders or the populations sense this hegemonic shift?

Schake: I love where you are going with this. Nobody’s ever asked me that question. Yes – when did they know? One of the interesting things I learned when doing the research is that Britain was never a comfortable hegemon in the way the United States wears its power with ease. I think because the successes that made Britain the ruler and enforcer of the international order were all coalition victories. Britain had to work with Spain and Portugal in the fight against Napoleon, and they had to bring the Prussians into the fight. All of their defining victories are coalition victories. So they never think of themselves with the ease of power that the U.S. does after World War II. They always worry that it is too expensive, that it is not worth it. There’s never a moment that they aren’t thinking it is slipping away from them – they are always worried it will.

That’s the biggest difference in my perspective from Aaron Friedberg’s brilliant book Weary Titan. He looks at a tight timeframe of about ten years when the transition actually occurs and he ascribes characteristics to the British in the twilight of their hegemony that were actually true of them in the entirety of it.

Nelson: Moving to contemporary issues and themes. Your book is timely, because in one way it is juxtaposed to Graham Allison’s recent book on the Thucydides trap, that we’ve already briefly touched on. So two questions regarding that: What are your thoughts on the concept of a Thucydides trap? And second, what do you want readers to take from your book, namely, if peaceful transition is possible, but rare, how do see the future of great power conflict?

Schake: Sir Lawrence Freedman wrote a review of Graham Allison’s book, that if anyone writes a review like that of my book, you can find my body floating in the river – way down [Laughter]. It’s devastating.

My view is that Graham should be laughing all the way to the bank because whether you agree with his argument or not, he defines Thucydides in a really interesting and important way. He and I are firing salvos at each other on the Cato Institute website right now. I wrote an essay on how to think about the rise of China that Graham and several other people critiqued. So now I’m getting ready to fire my second salvo at them. It’s really fun. I’m learning a whole bunch from other people’s perspective on the problem.

My sense of the Thucydides story is different than what comes across in Graham’s book. Having talked to him about it several times and debated it with him several times, he doesn’t think that’s all that Thucydides says . There’s so much you can take from Thucydides. The way it comes through Graham’s telling of the book is a more narrow reading of Thucydides than I think is fair to Thucydides – which is a big beautiful canvas of a story, and I think Graham agrees with that.

I don’t think it is a trap because, again, people make choices. The Athenians make choices, Pericles is playing a dangerous game, there’s a lot going on there that makes it interesting. I also don’t think it describes the United States, which after all has encouraged the rise of the rest of the world. We have encouraged an international order where our power is constrained by rules and institutions, and patterns of cooperation that are mutually beneficial.

John Ikenberry gets America in the time of its primacy exactly right. We shape the international order as a microcosm of our domestic political order. That’s why we face so few challenges to our dominance. That’s because most other countries think the current international order is better than they would get any other way. And that’s what we see playing out with China right now. Everyone wants the American order.

Nelson: This gets to your conclusion in your book. If peaceful transition is rare but possible, what do think happens in the next decade?

Schake: I think the way to bet your money is that hegemonic transitions will be violent. The only exception is the Britain-to-American transition. Because of the U.S.’ westward expansion, the consolidation of the American continent, after fighting the Indian Wars, we become an empire in our own minds. We come to have imperial reflexes because of our conquest of the West. So during this 20th century transition, Britain has become a democracy while we are becoming an empire. So we look similar to each other but different to everybody else. That sense of sameness created space for policy comprise. Political scientists hate squishy stuff like this – and they’re right, it’s not rigorous, it’s impressionistic. But what I learned trying to understand this one transition in great detail is that that was what mattered. That sense of sameness, that sense we were like each other and different from everybody else allowed for compromise.

So what to look for in future hegemonic transitions is that squishy intellectually unsatisfying definition of sameness, which takes us to Hegel and Frank Fukuyama, because China doesn’t feel similar to the U.S. right now. And if you think China can continue to rise without playing by the rules of the American order, and if you think as has been the case for the last 40 years that China can continue to rise without liberalizing, then it is very likely to be a violent transition.

I’m skeptical China can continue to rise without liberalizing because I think the law of gravity applies to them as well. It seems to me that, like Maslow’s pyramid, as people’s basic needs are met they become more demanding political consumers. So the challenge to China will be things like moms demanding safe baby milk, and parents infuriated that corruption meant building codes weren’t followed so schools collapse in earthquakes and kids get killed. You see an awareness of that risk in the anti-corruption campaign in China. I don’t think authoritarian societies get honest enough feedback to stay ahead of problems. In free societies you are always having to answer the question, for example, if you want to confiscate somebody’s property to run a high-speed train through it, you have to win the argument; in authoritarian societies where you don’t have to win the argument, I don’t see how they stay honest. I think the question is less about a hegemonic transition with a rising China, but rather: can China be successful in light of what its own citizens want?

Nelson: What would you recommend others read about this topic after they’ve finished your book? Specifically, what would you recommend someone read on this topic that takes a contrarian view?

Schake: There’s so much good material on this subject. Walter Russell Mead’s God and Gold is a great book that has a very different take than I do. He’s much more of the belief that British and Americans considered themselves similar. I think it is a late-developing consciousness. Walter treats it as having the model right and passing it from one to another with a certain inevitability of its success.

But when I read World War II history it makes me derisive when contemporary policy makers say today is way more complicated than it ever was and nobody has had challenges as difficult as we do. Man, a lot of American leaders back then would trade their problems with some of our challenges. Fighting Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany simultaneously is a lot harder than what we’ve been called to do today. This is a long circuitous route to tell you where Walter and I disagree: Walter gives a sense of inevitability. I think the story is so much more interesting when you realize how fearful the leadership was in the 20th century that they would lose.

We think of World War II in broad, heroic terms because we know the outcome. But the people who had to make decisions at the time – for instance, whether you go to Europe first or fight the Asian campaign first – was a question of enormous consequence and the continuation of the Republic hung in the balance.

Bob Kagan’s work on America and the liberal order and Walter Russell Mead’s work – I admire them both so much – but in both cases I think they failed to embrace how close-run American successes have been. I also think, including John Ikenberry, who writes so beautifully about America in the 20th century, they don’t get their arms around the brutality of the U.S. in the 19th century. We were a democracy, but Britain was right, we were an illustration of what was to be feared about a democracy because we were profoundly illiberal. And not just on the slavery issues. The Indian Wars go on for 50 years after the abolition of slavery and almost nobody blanched about the barbarity of that. In the great state of California, it was legal up into the 1920s to take Native American children away from their parents.

One of the questions that animated me to want to understand this American history better was trying to understand how a political culture so proud of our Republican values could live the history we lived in the 19th century and still become what we are in the 20th century. That animates a lot about how I try to tell the story in the book.

Nelson: Professor, to close on a lighter note, and not related to your book, what have you been reading lately – fiction, non-fiction – that you’ve particularly enjoyed? Articles, books? Longform journalism?

Schake: As it happens, I have six books on my nightstand at the moment that I am reading. The first is Emily Wilson’s splendid, sparkling new translation of The Odyssey. I think about Odysseus and his story differently because of her translation. If you think about the opening lines of Fagel’s translation of The Odyssey: “Tell me Muse of the man of twists and turns.” Emily Wilson’s translation of that line is, “Tell me Muse of a complicated man.” She conjures a completely different approach. I am just reveling in how differently to think about a book I know well because of a translation. It’s wonderful.

The next book on my nightstand is The War that Killed Achilles. It’s about the lessons from the Trojan War.

The third book on my nightstand is Emily Fridlund’s novel The History of Wolves. I haven’t started it yet, but my sister read it and thought it was brilliant.

The fourth is Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Goon Squad – it won the Pulitzer Prize. I love her writing.

Next on the list is Czeslaw Milosz’s The Captive Mind. I believe Phil Klay, the great short story writer and novelist, said this was a book that was important to him.

Finally, Cardinal Robert Sarah’s The Power of Silence. The good and great Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson recommended this book to me.

Nelson: And websites that you like to visit from time -to-time?

Shacke: You know where I’m going to start. I really enjoy War on the Rocks. I also really like The Strategy Bridge, Divergent Options, and I read everything Mira Rapp-Hooper and Tamara Cofman Wittes write because I always learn from them.

Nelson: This was wonderful. Thanks again for taking the time to chat.

Schake: Thank you, Chris. I really enjoyed this.

Dr. Kori Schake is the Deputy Director-General of the International Institute for Strategic Studies. She is the author of Safe Passage: the Transition from British to American Hegemony (Harvard, 2017) and editor with Jim Mattis of Warriors and Citizens: American Views of Our Military (Hoover Institution, 2016). She has worked for the National Security Council staff, the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff, and both the military and civilian staffs in the Pentagon. In 2008 she was senior policy advisor on the McCain presidential campaign. She taught Thinking About War at Stanford University, and also in the faculties of the United States Military Academy, the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, and the University of Maryland.

Christopher Nelson is a U.S. naval officer stationed at the U.S. Pacific Fleet Headquarters in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. He is a graduate of the U.S. Naval War College and the Maritime Advanced Warfighting School in Newport, RI. He is a regular contributor to CIMSEC. The questions above are his own and do not reflect those of the U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy.

Featured Image: Cover of Puck magazine, 6 April 1901. (Columbia’s Easter bonnet / Ehrhart after sketch by Dalrymple.)