This article originally appeared on Medium and was republished with the author’s permission. You can read it in its original form here.

By Anne Gibbon

Design thinking is beloved by many, and is more than a flash in the long list of new management tools. Why? Because it’s embodied learning. In recruiting your body, emotions, and rational brain to explore problems with others, we get to better solutions than pondering them alone in a cubicle. But for messy problems and large bureaucracies, design thinking alone isn’t sufficient. Systems dynamics appears to be the discipline of choice, but up to this point, the theoretical underpinnings have been developed to the exclusivity of embodied exercises.

This is my story of learning to facilitate design thinking as an embodied experience, rather than an intellectual exercise, and to begin to include systems thinking into the work. I have faith that the small prototypes will eventually snowball and make a greater impact than well written policy think pieces alone.

I confess, I put bandaids over my piercings. I never should have done that, I should have just taken them out — but the piercings are more me than the uniform these days.

Thirteen months after finishing ten years of service in the Navy, and days after finishing a fellowship at Stanford’s Design School, I put my foot down and really stretched my rebel wings. I got a very small nose piercing and three studs in one ear, most people don’t even notice them. But to me they are freedom. My problem: I still had to show up at Navy Reserve drill weekends with a proper uniform on. Too bad I never did ‘uniform inspection’ very well. One weekend someone complained about my pink nail polish and the gold ball earrings that were 2mm too big; I think she would have fallen out of her chair if she had discovered the band aids weren’t covering scratches.

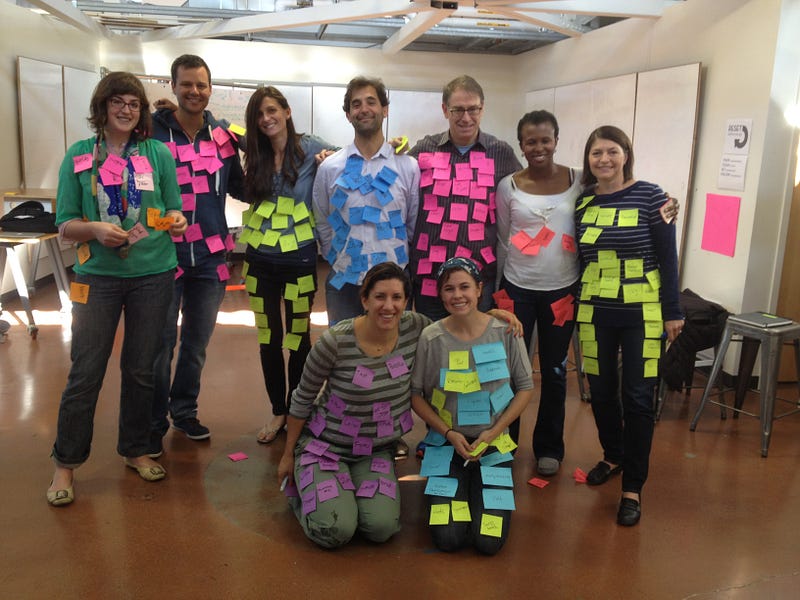

For the last two years of running design thinking workshops for various ranks and departments of the military, I have done the equivalent of putting band aids on piercings. We used Post-It notes and sharpies, but I usually left the improv at home. And the effect was an often neutered process. I led the groups through exercises and talked about modes of thinking — deductive, abductive, and inductive — as a way to make the creative, messy work more palatable to people who spent lives in frameworks so narrowly defined that playing at charades with their colleagues would have represented an existential crisis.

Design thinking has been the bright shiny magic wand that somehow hasn’t lost its luster. HBR gave it some east coast gravitas by featuring the process on the cover of their September issue. Popular in many management and product design circles, design thinking continues to spread. The White House just published a post about the use of Human Centered Design (HCD) by the USDA and the Office of Personnel Management’s Innovation Lab to improve the National School Lunch Program. My parents are still confused that I make a living writing on post its, but I feel lucky to be one of the many professionals using this process and adapting it for the real world. Fred Collopy, a professor of design and innovation at Case Western University has spent a career immersed in the theories of decision science, systems thinking, and design. He makes the point that design thinking has been so successful as a practical tool to effect change in organizations precisely because practitioners engage with it first by doing — not by thinking through the associated theories. Fred makes the point that systems thinking failed to spread widely as a management tool, not because it isn’t applicable, but because the discipline didn’t make the leap from theory to embodied exercises. The arcane details of the theories were and are hotly debated by a few, with the result being that the practical exercise of the main concepts are lost to the rest.

In large part, design thinking has avoided this trap because some of the most successful schools teaching the process are schools of practice, not ivory towers of thought. While I personally love dissecting the minutiae of different modes of thinking, the advances in neuroscience that allow us to explore augmented sensing, and the role that the autonomic nervous system plays in reaching creative insight, I reserve that for my fellow design practitioners. I’ve learned that when I’m leading a workshop, my job is to be the chief risk taker for the group, the leader in vulnerability. Their job is to embody each step in the process, and by fully immersing themselves, stumble into surprising reframes, 1000 ideas for a solution, and a few brilliant, wobbly prototypes.

While Fred’s article describes design thinking more as an evolution to systems thinking, I see them as complementary disciplines. Systems dynamics is worth plumbing intellectually, but for the purpose of emerging on the other side with methods and exercises that can be used as tools in the world, similar to the 5 step design thinking process from Stanford’s dschool. The complex theories associated with systems thinking and systems dynamics have at their root a set of ideas very similar to design thinking — engaging a broad set of stakeholders, using scenarios to explore them, reframing problems, and iterating. I want to explore what they might do together, with both disciplines having a rich underpinning of theory and accessible, embodied exercises.

Over a period of about seven months this year, I consulted (civilian role, not reservist) for the Pacific Fleet. I worked for a staff function in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and got the best of both worlds — the camaraderie that is a unique joy known to those who have served, and the luxury of wearing hot pink jeans to work. I learned a lot about myself as a designer and a facilitator. At the end of those months, I wrote a long report on how design thinking and systems dynamics might serve the vision of the Pacific Fleet commander, Admiral Swift. The staff that hired me didn’t ask for any insights on systems dynamics, but I gave it to them anyways.

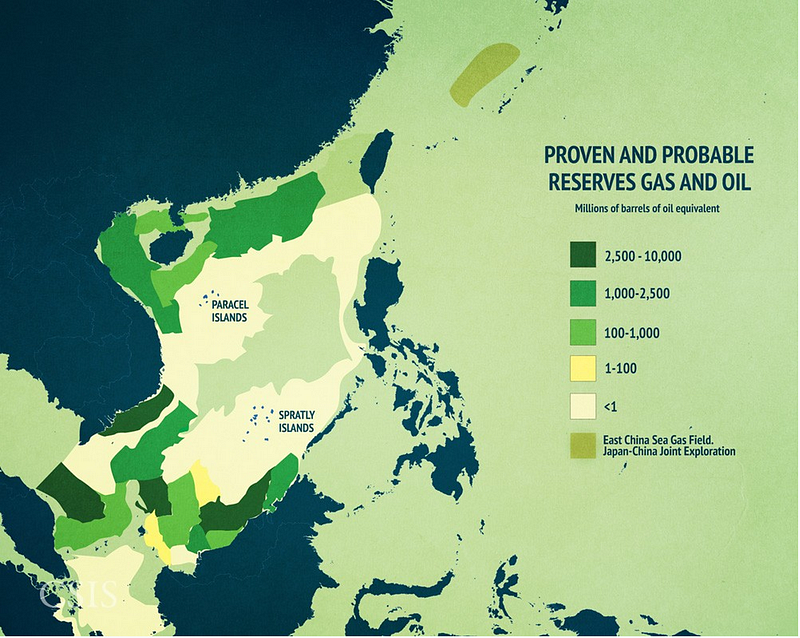

The Pacific Fleet needs uniformed practitioners of design thinking and systems dynamics who understand the theoretical nuances and who can also lead the embodiment of the exercises. They need this because the messy military problem they concern themselves with — maritime security — can’t be silo’ed into the pieces that only relate to the military, leaving other aspects to diplomats and environmentalists. Maritime security in our era is about rapidly declining natural resources, extreme climate events, rising levels of violence at sea, but more importantly, these different forces affecting maritime security are so interconnected that they require intense collaboration with unexpected partners. I fear that if we frame the problem of maritime security as an issue between great powers best left to great navies, we will miss the dynamics influencing the global system that supports human flourishing — our food, our climate, and many people’s freedom. (Did you know about the extent of slavery at sea?)

I don’t have a suggestion for how to frame the problem of human flourishing and maritime security in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. I have my own opinions, but I would rather they be challenged and iterated on through a process that mixes systems and design thinking. How should the Pacific Fleet approach the challenge of understanding and leveraging the system of maritime security in Indo-Asia? Instead of policy, I suggest behaviors I think Admiral Swift would want to observe as patterns in his Fleet.

- Encouraged collaboration — Leaders emerge from the crowd, assume the role of creative facilitator, and ensure collaboration when it’s needed.

- Innovation at sea — Sailors innovating ‘just in time’ on deployment lead to non-traditional employment of fielded capability.

- Using patterns — Sailors provide context, not single data points. Leaders guide the mastery of knowledge and foment the curiosity to identify and exploit patterns of action.

- Decentralized Execution — Leaders prepare subordinates to be decision-makers, challenging them to gain insights on context and patterns.

- The crowd organizes itself — Communities of interest will proliferate, building networks between the silos of the operational, maintenance, and R&D force.

- The crowd learns together — The Fleet leads the debate of war fighting instructions and populates a shared electronic repository of FAQ’s and how-to resources.

My contract ended with the Pacific Fleet at the end of July, and in keeping with my commitment to spread my wings, I’m leaving for New Zealand to work and play with food and agriculture technology and innovation ecosystems. But first, my own embodied prototype of decentralized execution. On October 26 and 27, a couple friends, a senior officer at the Department of State and a PhD futurist, and I will co-facilitate a design workshop in San Francisco on maritime security. We’re inviting a wildly diverse group of participants and we’re going to test new methods for embodied systems thinking. There’s no contract guaranteeing pay and no senior leader who has promised to take the prototypes from the workshop and shepherd them to execution.

Which means there are no rules on this adventure. We’ll publish the exercises mixing systems dynamics and design thinking, and we’ll share the prototypes — hopefully you’ll test them. Please get in touch if you’re interested in more detail.