This article by Dr. James Kraska was originally published at The Diplomat. It is republished here with the author’s permission.

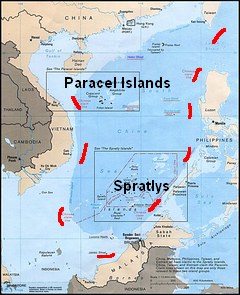

Since 2009, when China asked the secretary-general of the United Nations to circulate its nine-dashed line claim to the community of nations, the world has stood in bewilderment at Beijing’s actions in the South China Sea. Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines have the most to lose over China’s gambit, and the disparity in power between them and China leaves them confounded and stunned – and privately, apoplectic. China’s policies have created a dangerous mess in the South China Sea. The irony is palpably bitter on nine distinct levels. Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines hold the key to the best chance to fix the mess.

The first irony is that during negotiations for the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the developing states reluctantly ceded freedom of navigation through straits and in the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) for exclusive offshore resource rights. Malaysia and Indonesia, in particular, were averse to free transit through the litany of straits that cut through their nations, such as the Strait of Malacca and Sunda Strait. They relented, however, because the benefits of the package deal, foremost of which included a 200 nm EEZ, overcame their hesitancy on free navigation. If you want to get something in maritime diplomacy – exclusive control over an area of ocean – you have to give something in return if the rest of the world is going to cede its rights.

China’s seizure of its neighbors’ EEZs shatters that bargain. The Third UN Conference on the Law of the Sea that produced UNCLOS was convened after Ambassador Avid Pardo issued a clarion call in the UN General Assembly in 1967 to designate the riches of the seabed as the common heritage of all mankind as a source of

development for the world’s poorest nations. Similarly, since 90 percent of the world’s fisheries lie within 200 nm of shore, the EEZ was created to ensure food security for developing states. Today the maritime states of Southeast Asia, more reliant on the sea than most, face the real prospect of losing their rightful bounty, even as they accepted they navigational provisions.

Second, China was a leader among the developing states pushing for increased and secure offshore fishing and mineral rights for coastal states. Now a first order power, China takes it all back. It is as though the United States, Japan and Russia, who successfully bargained for liberal rules to protect freedom of navigation in exchange for recognizing the EEZ, agreed to give up the right to distant water fishing. Then decades after signing the treaty, the maritime powers began again sending industrial factory fishing vessels to scour the EEZs of the developing world.

The United States, which initially opposed creation of the EEZ and is not a party to UNCLOS, promotes and respects other countries’ EEZ rights; China, which championed the EEZ, is a party to UNCLOS and yet does not respect the EEZ rights of its neighbors.

Strategic Hegemony

Third, at its core, the dispute between China and its neighbors is not about China’s voracious appetite for resources, but rather about fortifying Beijing’s power and strategic hegemony in East Asia. The irony is that there are few resources to be had in the South China Sea. Only CNOOC, the Chinese state-controlled offshore oil company, suggests there are large reservoirs of oil and gas in the South China Sea. The U.S. Energy Information Administration, in contrast, believes that although the South China Sea contains perhaps 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, those resources mostly reside in undisputed areas along the coastline outside of China’s nine-dashed line claim. Likewise, while the fisheries of the South China Sea once were rich, in recent years they have been grossly depleted. China operates the largest fishing fleet in the world, and is principally to blame. While the hydrocarbons and fishing resources are not enough to move the dial on the Chinese economy, they are critically important for the smaller populations and economies of Vietnam, Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Brunei. The resource angle is a Chinese canard to mask a bold and strategic move.

Fourth, China serially insists on heartfelt and unique “interpretations” of international law to justify its South China Sea policy that lack any support outside China. We are told to abandon ethnocentric notions of international law and accommodate China’s outcome-based, albeit relatively recent way of thinking. Yet Beijing has demonstrated a sophisticated and patient adherence to the international law of land boundary disputes and signed fair and balanced treaties with 13 of 14 of its neighbors. It is as though there are two sets of Chinese Foreign Ministry lawyers – one informed by principles of international law and accepted norms, and another that appears incredulous to the most basic rules of the history, norms, and practices in the law of the sea. Chinese officials and scholars have been subject to an onslaught of tutorials and protests on maritime law by foreign lawyers and policy makers at countless official and Track II conferences and dialogues. The predictive pattern: The rest of the world argues until it is blue in the face, and Chinese representatives appear not to get it.

The only impediment to this theory, however, is that ironically China appears to actually understand the law of the sea when it is in its interest to do so. China has quietly reached amicable and even-handed agreements with both Vietnam and South Korea in the Gulf of Tonkin and Yellow Sea, respectively, to responsibly and equally divide fisheries and conduct joint enforcement patrols that reduce tension. Cooperation in these areas is strong and enduring, yet it attracts no media attention and elicits no question why China understands law of the sea norms in these areas, but utterly fails to grasp them in the South China Sea.

The fifth irony is that China has pocketed the rights it gained in UNCLOS, but had dodged its responsibilities. As a leader in offshore enclosure, China was a leader among a group of states from Asia, Africa, and Latin America, to expand the territorial sea from 3 nm to 12 nm and create the 200 nm EEZ. As a package deal, China and other state parties have a legal obligation to accept the obligations of the treaty along with the newly created rights. China has failed to observe its obligations to other states operating in its own territorial seas and EEZ. For example, China attaches conditions to the right of innocent passage in the territorial sea and freedom of navigation in the EEZ that not only are nowhere in UNCLOS, but were specifically rejected by the world community during the negotiations. Just as China fails to accept its obligations toward foreign ships and aircraft in its own EEZ, it has enjoyed the rights and freedoms of UNCLOS in other countries’ EEZs.

Dubious Claim

Sixth, even a sweepingly generous and sympathetic application of international law in favor of China’s claims fails to give Beijing anything more than a handful of tiny maritime zones in the region. Although China has declined to clarify the meaning of its nine-dash line

and islands of the South China Sea. The numerous reefs, low-tide elevations, and skerries, however, are not subject to legal title and belong to the state on whose continental shelf they are located. While China has asserted a claim to the rocks and islands based on historic discovery, it has not put forth even a prima facie case to support such an audacious claim.

A prima facie case is one that asserts material facts and relevant law that would allow a judge to decide the case in favor of the proponent. In this case, however, even if one accepts as true that everything that China has said about its history in the region – a dubious proposition to be sure – China fails to assert a lawful claim. While China claims that its ancient records show that Chinese seafarers visited and named some of the rocks in the Spratly and Paracel Islands, it is not clear that the voyages were made as an official function of state or simple happenstance recorded by anonymous fishermen. As a matter of law, even if agents of the emperor visited the rocks and claimed them on his behalf, the visits are legally immaterial in the same way that the U.S. visits to the moon do not confer upon the United States legal title to that celestial body.

Mere discovery by itself is not a lawful basis for acquisition of territory, as the U.S. learned when it lost the seminal Island of Palmas arbitration in 1928. The island of Palmas lies between Indonesia and the Philippines, and the governments of the Netherlands and the United States, as colonial powers, submitted the dispute to arbitration. Although the United States asserted a claim of historic discovery on behalf of the Philippines from Spanish explorers, the arbitration panel awarded the island to the Netherlands because simple discovery without effective governance extending over a long period of time was immaterial as a matter of law. Island of Palmas is the most important case to uphold the legal principal that mere historic discovery is immaterial; other precedents include the Clipperton Island arbitration (France v. Mexico, 1933). In that case, Mexico, like the United States in the Palmas case, traced its claim of sovereignty from Spanish discovery. The arbitration, however, awarded the small feature to France based upon French occupation and usage.

Similarly, in the 1953 case at the International Court of Justice over the Minquiers and Écréhous groups in the Channel Islands, the court rejected a French claim based on historic presence and fishing rights that is remarkably similar to Chinese historic claims in the South China Sea. Instead, the court awarded the features to England based on subsequent exercise of jurisdiction over them by the Manorial court of the fief of Noirmont in Jersey. Furthermore, even assuming beyond the evidence that China actually had lawful title to the rocks and islands, it lost them long ago. This has nothing to do with Western imperialism, but rather China’s closure to the rest of the world. Inactivity and lack of official presence in a feature constitutes abandonment of title over time.

Maritime Zones

Seventh, while China has not made a prima facie case, let’s assume that it magically acquired legal title to every one of the rocks and islands in the South China Sea. In this case, under the law, China could be awarded only tiny maritime zones around them. States seek to augment or buttress their claims to tiny features in the vain hope that they can secure large maritime zones of sovereignty, sovereign rights, and jurisdiction over the adjacent waters. The mindset that a nation can strike a bonanza of offshore territory and wealth from a tiny dot of coral is one of those “too good to be true” stories that never seem to die. Apparently, the potential jackpot for making such claims is too great to resist. A mid-ocean low-tide elevation, which is below water at high tide, but above water at low tide, is not entitled to any territorial sea. Zero.

A tiny rock jutting above water at high tide generates a territorial sea of only 452 nm2. In contrast, a bona fide island capable of sustaining human habitation or an economic life of its own generates an EEZ of 125,664 nm2, an area more than 275 times larger. Of course, if any of these zones overlap with another country’s zones, they have to be adjusted, and in the South China Sea, there’s the rub. International courts have uniformly rejected the idea that small features of any sort are entitled to large maritime zones, but the judgments in cases of overlapping zones are especially harsh. In the 2012 case between Nicaragua and Colombia at the ICJ, for example, the Court awarded legal title to Colombia to two tiny rocks, and then confined them within 12 nm territorial sea enclaves set within Nicaragua’s EEZ. The court did so by comparing the vast disparity of shoreline facing the area of ocean subject to dispute, and noted that while Columbia had minimal shoreline from its rock possessions, Nicaragua’s shoreline generated by its lengthy mainland coast was eight times longer. This principle of shoreline disparity examines only that coast from islands or mainland that actually face toward the opposing disputant, and it is particularly salient for the ASEAN states vis-à-vis China in the South China Sea. Take Vietnam, for example. Vietnam has a 2,200 km coastline facing the South China Sea, which is hundreds of times greater than the combined coastline of every rock and island in the region that faces Vietnam. Under the ICJ formula, Vietnam is accorded a vast, normal EEZ from its long coast, and whichever country has title to the islands within Vietnam’s EEZ would be afforded a very minimal zone. The precedent suggests that rather than winning the jackpot, the state with title to tiny, insignificant features that lie within another country’s EEZ are awarded rather tiny and insignificant rights over the nearby water.

Eighth, China’s herculean effort to construct and occupy new artificial islands in the South China Sea is also legally nugatory. China has constructed enormous artificial islands from seven reefs: Mischief Reef, Gaven Reef, Hughes Reef, Subi Reef, Fiery Cross Reef, Johnson Reef, and Cuarton Reef. Analysis at Middlebury College identifies each of these reefs appears to be a low-tide elevation; the Philippines has suggested in its arbitration filing against China that the latter three are rocks.

No matter how large an artificial island is constructed, it cannot acquire additional or new legal rights over what it is entitled to in its natural state. While China has expended enormous political capital and scared its neighbors into unprecedented embrace of the United States, India, and Japan, it has actually weakened, rather than strengthened its legal position in the South China

Sea. Why? Because the burden of proof of whether a feature is in its natural state a rock entitled to a 12 nm territorial sea and not a low-tide elevation entitled to nothing lies with the claimant. But now that China has so irreparably tampered with the evidence, it is virtually impossible to divine the natural state of its artificial islands. Some sources have recorded all of the features as mere low-tide elevations, whereas others say that at least some may be rocks. We may never know for sure now that China has hideously transformed them.

Appreciating Irony

The ninth and final irony in the South China Sea is that the principal coastal states that stand to benefit from the rule of law do not fully appreciate the ironies and so far have been unable to form a coherent approach to preserve their rights, yet the key is solely within their grasp. Brunei and Indonesia do not claim any feature in the South China Sea. Their EEZs are encroached upon by China, but because they claim no rocks, they are secondary to the disputes. Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines all assert far-reaching claims over various reefs, rocks and islands in the region. These three frontline states have the most to gain from cooperation, and the most to lose from Chinese maritime hegemony. These states must recognize now that they face an imminent threat of losing their EEZ to China, but how can they secure their moral and legal inheritance from UNCLOS?

First, Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines should renounce their claim to any feature that is within the natural EEZ generated by a neighboring mainland or large island coastlines, such as Borneo, Mindanao, and Palawan. The same greed and historic hogwash that drives China’s audacious claims also sometimes attracts the frontline states, ruining any chance that they can work together. Only by renouncing legally specious claims against tiny features that generate tiny maritime zones can these states ensure that they preserve the EEZ. For developing states, the EEZ was the crown jewel of rights and jurisdiction in UNCLOS, and insistence upon unrealistic claims against their neighbors only ensures that they will lose it all. Unless these states work together, they will slowly but surely lose their EEZs, the principal inheritance that the law of the sea conferred on developing states.

If Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines can foreswear a claim of title to any feature within the EEZs of its neighbors, they can present a united front against China. Unity among the three nations is the best bet for galvanizing support within ASEAN, and by the member states of the European Union and NATO, and perhaps even Russia. By further diplomatically isolating China, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia drastically raise the costs for Beijing, while lowering the costs for states outside the region to support them. American support for such a plan, for example, levels the playing field, while nominally avoiding “taking sides” with a particular claimant. By giving up legally unsupportable claims that encroach on their neighbors EEZs, the frontline states assure they enjoy their rightful legacy of UNCLOS.

James Kraska is professor in the Stockton Center for the Study of International Law at the U.S. Naval War College and senior associate with the China Maritime Studies Institute, also at the Naval War College.

Featured Image: CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Strategy Initiative via Reuters.