Are there connected Chinese strategic themes that cut across the contested and interlinked global commons (domains) of maritime, space, and cyberspace? If so, what are they and what could the United States do about them?

By Tuan N. Pham

Last November, I wrote an article titled “China’s Maritime Strategy on the Horizon” highlighting a fleeting strategic opportunity for Washington to shape and influence Beijing’s looming and evolving maritime strategy. I posited that Chinese maritime strategists have long called for a maritime strategy; China’s maritime activities are driven by its strategic vision of the ocean as “blue economic space and blue territory” crucial for its national development, security, and status; and Beijing may be trying to fill domestic legal gaps that it sees as hindering its ability to defend territorial claims in the South China Sea (SCS) and East China Sea (ECS), and justify its growing activities in international waters. The latter point is underscored by recent media reports from Beijing considering the revision of its 1984 Maritime Traffic Safety Law, which would allow Chinese authorities to bar some foreign ships from passing through Chinese territorial waters. If passed, this will be another instance of China shaping domestic maritime laws to support its developing and evolving maritime strategy, and part of a larger continuing effort to set its own terms for international legal disputes that Beijing expects will grow as its maritime reach expands.

I then further suggested that Beijing’s forthcoming maritime strategy will shape its comportment and actions in the maritime domain in the near- and far-term, and perhaps extend into the other contested global commons of space and cyberspace as well. In Part 1 of this two-part series, I explore this potential cross-domain nexus by examining the latest Chinese space white paper and cyberspace strategies. In Part 2, I will derive possibly connected strategic themes that cut across the interlinked global commons and discuss how the United States could best respond.

China’s Space Activities in 2016 White Paper (December 2016)

“To explore the vast cosmos, develop the space industry, and build China into a space power is a dream we pursue unremittingly.”

On December 27, 2016, China’s Information Office of the State Council published its fourth white paper on space titled “China’s Space Activities in 2016.” The paper and the preceding 2011, 2006, and 2000 papers largely follow a pattern of release, sequenced and synchronized with the governmental cycle of Five-Year Plans that are fundamental to Chinese centralized planning. Last year’s paper provides the customary summary of China’s space accomplishments over the past five years and a roadmap of key activities and milestones for the next five years.

Since the white paper was the first one issued under President Xi Jinping, it is not surprising that the purpose, vision, and principles therein are expressed in terms of his world view and aspiration to realize the Chinese Dream of national rejuvenation. Therefore, one should read beyond the altruistic language and examine the paper through the realpolitik lens of the purpose and role of space to the Chinese Dream; the vision of space power as it relates to the Chinese Dream; and principles through which space will play a part in fulfilling the Chinese Dream. Notable areas to consider include Beijing’s intent to provide basic global positioning services to countries along the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road in 2018; construction of the Belt and Road Initiative Space Information Corridor; strengthening bilateral and multilateral cooperation that serves the Belt and Road Initiative; and attaching the importance of space cooperation under the Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS) cooperation mechanism and within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).

Although the white paper is largely framed in terms of China’s civilian space program, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is subtly present throughout the paper in the euphemism of “national security.” The three references in the purpose, vision, and major tasks deliberately understate (or obfuscate) Beijing’s strategic intent to use its rapidly growing space program (largely military space) to transform itself into a military, economic, and technological power. In short, China’s space program does not have structures in place that make meaningful separation between military and civil programs, and those technologies and systems developed for supposedly civil purposes can also be applied–and often are–for military purposes.

The white paper highlights concerted efforts to examine extant international laws and develop accompanying national laws to better govern its expanding space program and better regulate its increasing space-related activities. Beijing intends to review, and where necessary, update treaties and reframe international legal principles to accommodate the ever-changing strategic, operational, and tactical landscapes. All in all, China wants to leverage the international legal framework and accepted norms of behavior to advance its national interests in space without constraining or hindering its own freedom of action in the future where the balance of space power may prove more favorable.

China’s National Cyberspace Security Strategy (December 2016)

“China will devote itself to safeguarding the nation’s interests in sovereignty, security, and development in cyberspace.”

On the same day as the issuance of the “China’s Space Activities in 2016” white paper, the Cyberspace Administration of China also released Beijing’s first cyberspace strategy titled “National Cyberspace Security Strategy” to endorse China’s positions and proposals on cyberspace development and security and serve as a roadmap for future cyberspace security activity. The strategy aims to build China into a cyberspace power while promoting an orderly, secure, and open cyberspace, and more importantly, defending its national sovereignty in cyberspace.

The strategy interestingly characterizes cybersecurity as “the nation’s new territory for sovereignty;” highlights as one of its key principles “no infringement of sovereignty in cyberspace will be tolerated;” and states intent to “resolutely defend sovereignty in cyberspace” as a strategic task. All of which reaffirm Xi’s previous statement on the importance of cyberspace sovereignty. At last year’s World Internet Conference in Wuzhen, Xi boldly exclaimed, “We should respect the right of individual countries to independently choose their own path of cyberspace development, model of cyberspace regulation and Internet public policies, and participate in international cyberspace governance on an equal footing.”

Both the space white paper and cyberspace security strategy reflect Xi’s world view and aspiration to realize the Chinese Dream. The latter’s preamble calls out the strategy as an “important guarantee to realize the Two Centenaries struggle objective and realize the Chinese Dream of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” Therefore, like the white paper, one should also read beyond the noble sentiments of global interests, global peace and development, and global security, and examine the strategy through the underlying context of the Chinese Dream. What is the purpose and role of cyberspace to national rejuvenation; the vision of cyberspace power as it relates to national rejuvenation; and through which principles will cyberspace play a role in fulfilling national rejuvenation? Promoting the construction of the Belt and Road Initiative, raising the international telecommunications interconnection and interaction levels, paving a smooth Information Silk Road, and strengthening the construction of the Chinese online culture are some notable areas to consider.

The role of the PLA is likewise carefully understated (or obfuscated) throughout the strategy in the euphemism of “national security.” The 13 references in the introduction, objectives, principles, and strategic tasks quietly underscore the PLA’s imperatives to protect itself (and the nation) against harmful cyberspace attacks and intrusions from state and non-state actors and to extend the law of armed conflict into cyberspace to manage increasing international competition – both of which acknowledge cyberspace as a battlespace that must be contested and defended.

The strategy also puts high importance on international and domestic legal structures, standards, and norms. Beijing wants to leverage the existing international legal framework and accepted norms of behavior to develop accompanying national laws to advance its national interests in cyberspace without constraining or hindering its own freedom of action in the future where the balance of cyberspace power may become more favorable.

China’s International Strategy for Cyberspace Cooperation (March 2017)

“Cyberspace is the common space of activities for mankind. The future of cyberspace should be in the hands of all countries. Countries should step up communications, broaden consensus and deepen cooperation to jointly build a community of shared future in cyberspace.”

On March 1, 2017, the Foreign Ministry and State Internet Information Office issued Beijing’s second cyberspace strategy titled “International Strategy for Cyberspace Cooperation.” The aim of the strategy is to build a community of shared future in cyberspace, notably one that is based on peace, sovereignty, shared governance, and shared benefits. The strategic goals of China’s participation in international cyberspace cooperation include safeguarding China’s national sovereignty, security, and interests in cyberspace; securing the orderly flow of information on the Internet; improving global connectivity; maintaining peace, security, and stability in cyberspace; enhancing international rule of law in cyberspace; promoting the global development of the digital economy; and deepening cultural exchange and mutual learning.

The strategy builds on the previously released cyberspace security strategy and trumpets the familiar refrains of national rejuvenation (Chinese Dream); global interests, peace and development, and security; and development of national laws to advance China’s national interests in cyberspace. Special attention was again given to the contentious concept of cyberspace sovereignty in support of national security and social stability – “No country should pursue cyberspace hegemony, interfere in other countries’ internal affairs, or engage in, condone or support cyberspace activities that undermine other countries’ national security.” The strategy also interestingly calls for the demilitarization of cyberspace just like the white paper does for space despite China’s growing offensive cyberspace and counterspace capabilities and capacities – “The tendency of militarization and deterrence buildup in cyberspace is not conducive to international security and strategic mutual trust – China always adheres to the principle of the use of outer space for peaceful purposes, and opposes the weaponization of or an arms race in outer space.” Incongruously, a paragraph after discouraging cyberspace militarization, the strategy states that China will “expedite the development of a cyber force and enhance capabilities in terms of situational awareness, cyber defense, supporting state activities, and participating in international cooperation, to prevent major cyber crises, safeguard cyberspace security, and maintain national security and social stability.”

Conclusion

This concludes the short discourse on the latest Chinese space white paper and cyberspace strategies and sets the conditions for further discussion. Part 2 examines possibly connected strategic themes that cut across the contested and interlinked global commons of maritime, space, and cyberspace, and strategic opportunities for the United States. Read Part 2 here.

Tuan Pham has extensive experience in the Indo-Asia-Pacific, and is published in national security affairs. The views expressed therein are his own and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government.

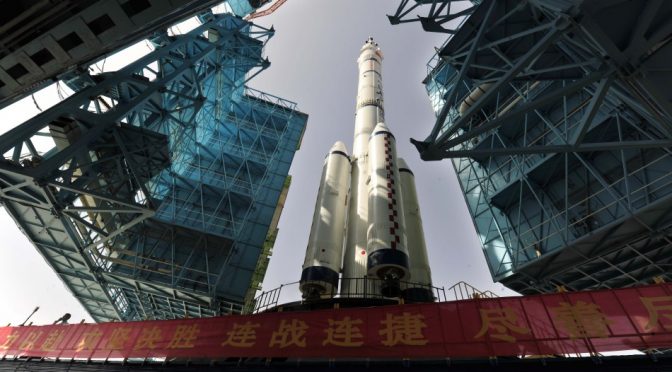

Featured Image: June 3, 2013. Assembly of the Shenzhou-10 spacecraft and the Long March-2F carrier rocket at Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in Jiuquan, northwest China’s Gansu Province. (Xinhua/Liang Jie)