By Ryan D. Martinson

On May 19th, a formidable new Chinese ship put to sea for the first time. As it left its berth at Jiangnan Shipyard, its onboard automatic identification system (AIS) transmitted signals for anyone who cared to receive them. Its identity, Zhongguo Haijing 2901. Its purpose, sea trials. Its heading, somewhere in the East China Sea.

This was not the voyage of the Red October. Zhongguo Haijing 2901 is not a stealthy nuclear submarine able to menace foreign capitals, or sink foreign fleets. Nor is it a sister ship to China’s Liaoning (CV-16), that other potent symbol of sea power, the aircraft carrier. Indeed, by naval standards, its combat capabilities belong to an earlier age—the 19th century.

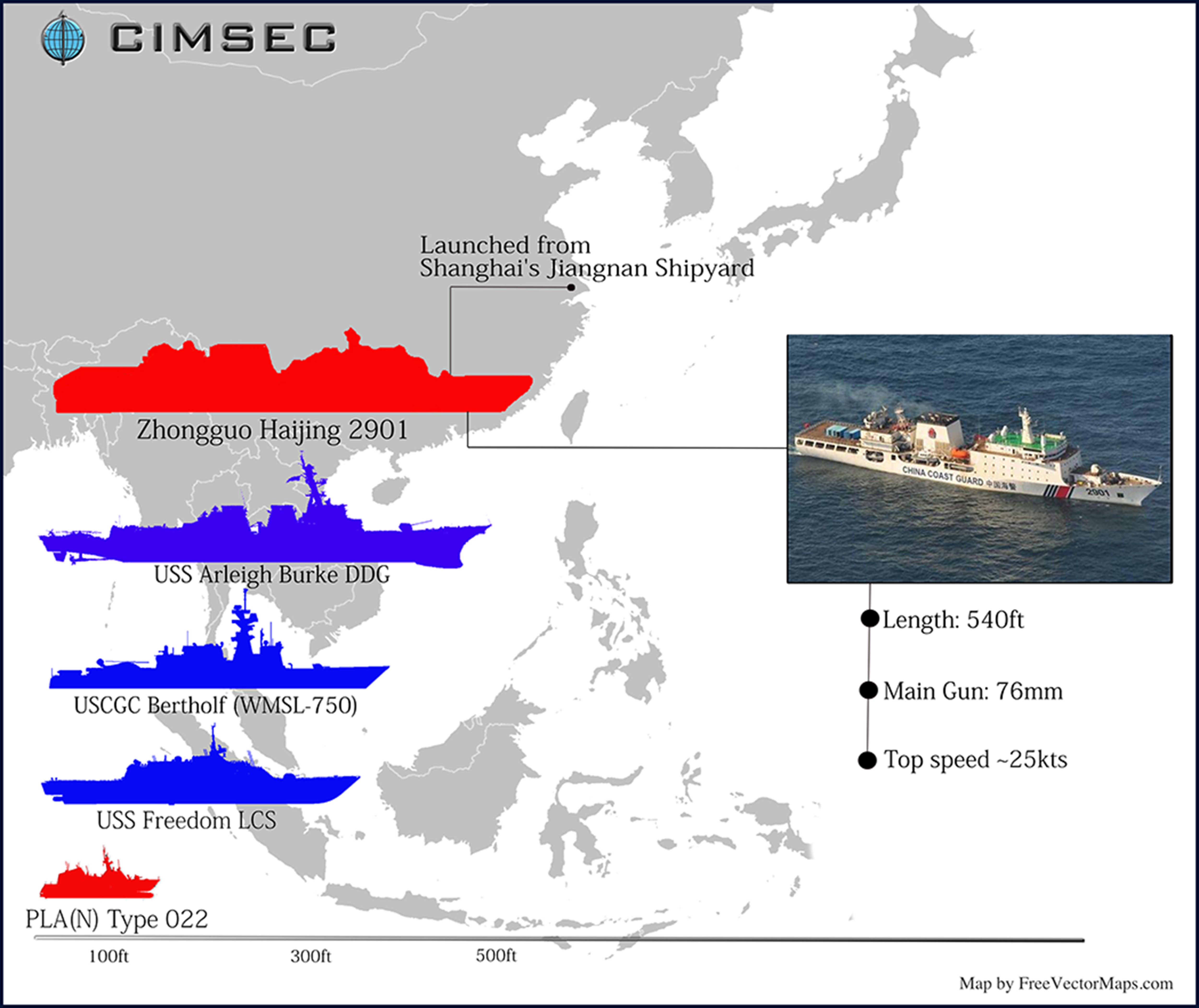

However, Zhongguo Haijing, or China Coast Guard (CCG) 2901, was not built to fight wars. At over 10,000 metric tons, it is by far the world’s largest constabulary vessel, a class of ship operating at the vanguard of China’s peacetime expansion in maritime East Asia. When it is commissioned sometime in the coming weeks, it will provide a huge advantage to China in the battle of wills taking place along its maritime periphery.

Building the Mega-Cutter

During the 2010-2012 period, Chinese policymakers made a series of decisions to vastly expand the capabilities of the country’s maritime law enforcement agencies. They envisioned a great fleet of ships charged with advancing Beijing’s claims to waters and islands hundreds of miles away from the mainland coast, performing what Chinese texts euphemistically refer to as “rights protection” operations. In the last two years, the China Coast Guard has received dozens of new ships, many of which have been used to buttress new footholds at Scarborough Reef, the Second Thomas Shoal, the Luconia Breakers, and the Senkaku Islands, and underwrite economic activities in disputed waters, most notably the two-month drilling operations of HYSY 981 in 2014. CCG 2901 is an outcome of this surge in shipbuilding.

That CCG 2901 would someday put to sea was not a secret. In July 2013, the head of China State Shipbuilding Corporation, Hu Wenming, declared that his company would “accelerate research and development” of maritime law enforcement cutters displacing between 4,000-10,000 metric tons. In January 2014, the research affiliate of another state shipbuilding firm revealed that the previous year it had signed a contract to do design work for this new ship class. By late 2014, Chinese netizens were posting photos of the ship in the latter stages of construction.

That CCG 2901 would be studded with deck guns was not a given. Indeed, it represents a noteworthy breach of precedent: almost all of the new ships procured by the China Coast Guard have been unarmed. This allows Chinese ships to aggressively engage the state and private craft of other countries without conjuring images of gunboat diplomacy or precipitating a war. With CCG 2901, the deterrent value of deck guns trumps these old aversions.

When it is commissioned, 2901 will be based at one of three cities with direct access to the East China Sea. Most likely it will be stationed along Shanghai’s Huangpu River, a hub of Chinese coast guard activity. It may eventually find a home at a large new base to be built further south in Wenzhou. It will primarily conduct missions to areas China disputes with Japan, including the sovereign waters adjacent to the Senkaku Islands. However like other ships based in these ports it will no doubt periodically patrol the South China Sea, working with sister units in Guangxi, Guangdong, and Hainan to impose the Chinese legal order in disputed waters.

CCG 2901 is the first, but not the last, of its class. A second ship is in the latter stages of construction at Jiangnan Shipyard. It will almost certainly be based at a facility with easy access to the South China Sea, probably on the banks of the Pearl River in the city of Guangzhou (Guangdong).

Sprinting to Superiority

Just a few years ago, the idea of Chinese maritime predominance was pure fantasy. This is illustrated in a little-remembered confrontation between Japanese and Chinese forces that took place in 2002. In December of the previous year, the Japan Coast Guard sank an armed North Korean trawler operating near the Japanese coast, an encounter that Wikipedia grandiosely calls the Battle of Amami-Ōshima.

After hours of fight and flight, the trawler ultimately went down in Chinese jurisdictional waters. Japanese policymakers decided to raise the wreck, causing consternation among Chinese leaders. The operation would involve questions of Chinese rights and interests embodied within the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which China ratified six years earlier. In response, Chinese policymakers instructed the China Marine Surveillance (CMS), a maritime law enforcement agency, to deploy a task force of ships to monitor the Japanese operations.

The CMS task force was ordered to “maintain presence and show jurisdiction,” that is, to be present to remind the Japanese who had authority. But if the Chinese record is any guide, it was clear that the Japanese were in charge. According to the recollections of the CMS task force commander, Liu Zhendong, Japan created a security perimeter around the site, barring Chinese access to the salvage operations. It could do so because it was able to muster many more ships: as many as 19 vessels, while CMS could send at most four, cobbled together from units from all over the country. Moreover, Japan’s cutters were much larger than China’s. Among the ships buttressing Japan’s security perimeter was the 6,500 ton Shikishima (PLH-31)—the world’s largest coast guard ship. In the end, China was forced to resort to guile to gain access to the salvage operations: it accused a Japanese ship of leaking oil, a violation of China’s environmental protection laws.

In little more than a decade, the tables have completely turned. While Japan has a much more capable coast guard in many respects—it operates far more and better aircraft; its ships are more capable, their crews better trained—its white fleet is now much smaller than China’s, at the same time that the area of waters under its administration is far larger. And of course, with the commissioning of CCG 2901, China, not Japan, will own the world’s largest coast guard cutter.

Bigger is Always Better

In the type of missions China’s coast guard is asked to perform, ship size is a key determinant of capability. This differs from modern naval combat, where a 225 ton boat firing long-range cruise missiles might level a 100,000 ton super carrier. While the China Coast Guard does use water cannons, sirens, and other non-lethal measures to cow foreign mariners, the primary instrument of coercion is the ship itself.

This advantage was illustrated in a May 2012 encounter between a Chinese maritime law enforcement vessel—the 4,000 metric ton Haijian 83—and a much smaller foreign ship, probably Vietnamese. As Haijian 83 sailed through disputed waters in the South China Sea, it was approached and ordered to leave by personnel on the foreign patrol vessel. As the two ships got closer, the Chinese commander requested permission from superiors ashore to engage. When this was granted, he ordered his ship to steam “full speed ahead” (kaizu mali), directly at the other craft. Given the size differential, the foreign ship had no choice but to retreat, which is what happened.

As this example shows, the type of confrontation taking place between non-naval vessels is akin to a game of chicken. When two ships are close in size, nerve and seamanship go a long way, since neither side wants a collision. When there is a major size disparity, the larger ship can simply drive others away. Indeed, when advantages in speed are combined with advantages size, a big ship can even sink a smaller craft. At least one Vietnamese boat suffered this fate during contentious encounters in waters surrounding HYSY 981 in mid-2014.

The Implications of China’s Maritime Megalomania

When CCG 2901 does eventually deploy to disputed waters in the East China Sea, Japan may have few options. Because of its enormous size, this ship will sail and operate at will. Japan will be forced to either accept its unfettered movements, or escalate the conflict, which it will naturally be reluctant to do. During a moment of bilateral friction, CCG 2901 may even attempt to expel Japanese Coast Guard ships operating near the Senkaku Islands. Again, in that case Japan’s decision makers, beginning with front line commanders, will be faced with very difficult choices. Chinese policymakers may assume Japan will back down no matter what China does. That would be a grave misjudgment. Thus, with the commissioning of CCG 2901, the possibility of a shooting war in the East China Sea increases.

The Chinese mega-cutter will play a different role in the South China Sea, where Chinese forces already outmatch other disputants. With its range and carrying capacity, it will be able to easily sail the great distances to China’s most remote claims and remain in disputed waters for long periods of time. Of most concern, these ships may engage foreign naval vessels, including those of the U.S. Navy. In April 2014, both China and the U.S. approved a Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES), an agreement to ensure professional behavior when foreign warships unexpectedly meet while on deployment. However, the document only applies to naval vessels: the ships of the China Coast Guard and other maritime law enforcement entities are not required to adhere to its provisions. Thus, U.S. naval commanders now must prepare for the possibility of testy encounters with Chinese mega-cutters on the high seas in peacetime, when their advanced weapons systems will do them little good. This is an uncomfortable prospect given that China’s mega-cutters are larger than most U.S. surface combatants and positively dwarf the 3,500-ton USS Forth Worth (LCS-3) that recently patrolled waters near the Spratly Islands.

The strategic and operational implications of CCG 2901 should be the primary concern of other states. But it is also important to reflect on the chain of policy decisions that willed CCG 2901 into being. China has invested hundreds of millions of yuan to design and build this ship, and will spend hundreds of millions more to man, maintain, and replenish it over the course of its lifetime. Yet it exists for a single reason: to help China achieve peacetime dominance in Chinese-claimed waters. Thus, the decision to build a class of 10,000-ton cutters should be seen as a measure of China’s resolve to prevail in its disputes.

Foreign states will no doubt react with fear and suspicion to the commissioning of these two armed mega-cutters. Chinese leaders must know this. Just as they must have known that placing HYSY 981 in Vietnamese-claimed waters and building bases in the Spratly Archipelago would result in handwringing among its neighbors. Not long ago, policies that risked inducing these emotions abroad found few supporters in Chinese councils of state. The decision to build these ships, then, is another brushstroke in the portrait of a leadership operating on new assumptions, a state that does not fear the costs of its expansionary behavior, or one that believes they can and should be borne for the rewards they redeem.

Ryan D. Martinson is research administrator at the China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI). He holds a master’s degree from the Tufts University Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy and a bachelor of science from Union College. Martinson has also studied at Fudan University, the Beijing Language and Culture University, and the Hopkins-Nanjing Center. He edits the CMSI Red Book series and researches China’s maritime policy. The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US Navy, Department of Defense or the US Government.