The National Interest on Monday published an intriguing article by Ted Galen Carpenter discussing the potential implications of President Obama’s current South China Sea (SCS) strategy. During the East Asia Summit, where the President was forced to send Secretary of State Kerry in his place so he could focus on the government shutdown, Secretary Kerry took a supportive (some would say meddling) position in defense of Manila stating that “all claimants have a responsibility to clarify and align their claims with international law. They can engage in arbitration and other means of peaceful negotiations.”

Although many welcome America’s “pivot” to Asia, many more are trying to grasp what that really means. Does it mean greater military presence, more economic influence? Or, as Carpenter’s article suggests, taking sides in the sovereignty disputes in which most of the tension in the region is moored? Before drawing conclusions that Secretary Kerry’s statement provides some sort of clue, it would be prudent to examine what the arbitration filing actually is and what it requests.

For background, the United Nation Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provides a dispute-settlement regime that requires signatory States, such as China and the Philippines, to resolve their disputes peacefully: first through negotiation, and then if that doesn’t work, States can choose from four options. These options include submission of the dispute to the International Court of Justice, to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, conciliation, or go to an arbitral tribunal. Without delving into too much procedural detail, the arbitral tribunal is usually the most attractive because it allows the States to choose who their adjudicators will be.

For background, the United Nation Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provides a dispute-settlement regime that requires signatory States, such as China and the Philippines, to resolve their disputes peacefully: first through negotiation, and then if that doesn’t work, States can choose from four options. These options include submission of the dispute to the International Court of Justice, to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, conciliation, or go to an arbitral tribunal. Without delving into too much procedural detail, the arbitral tribunal is usually the most attractive because it allows the States to choose who their adjudicators will be.

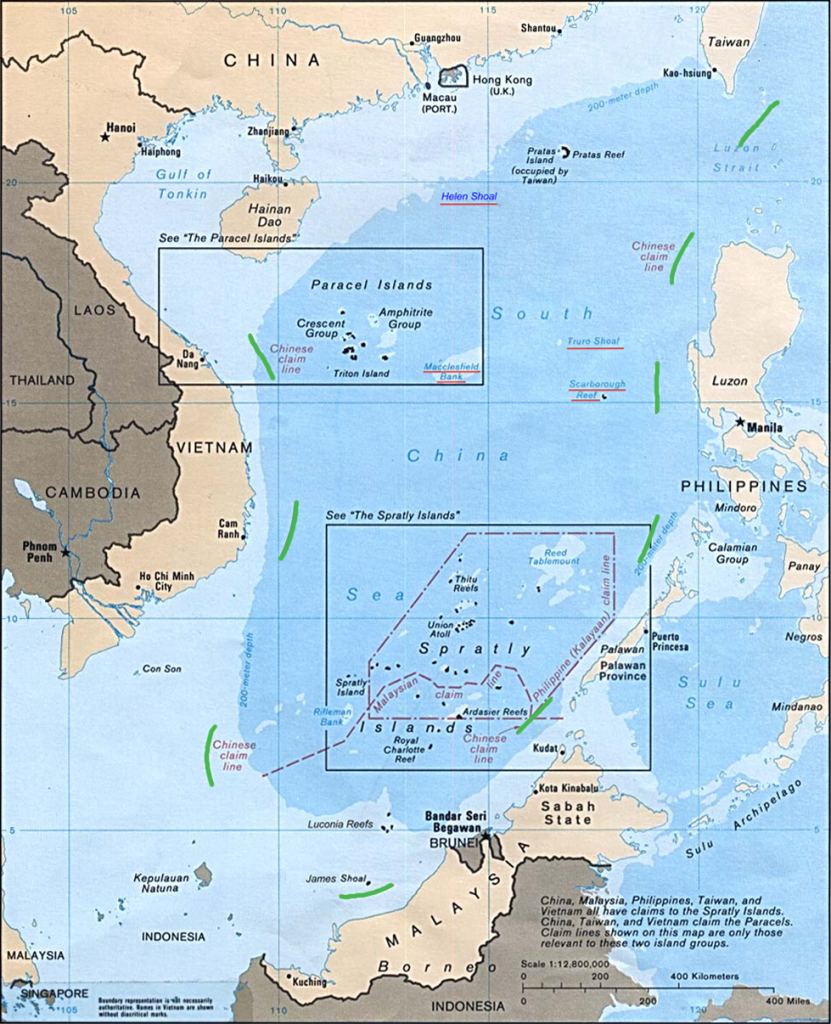

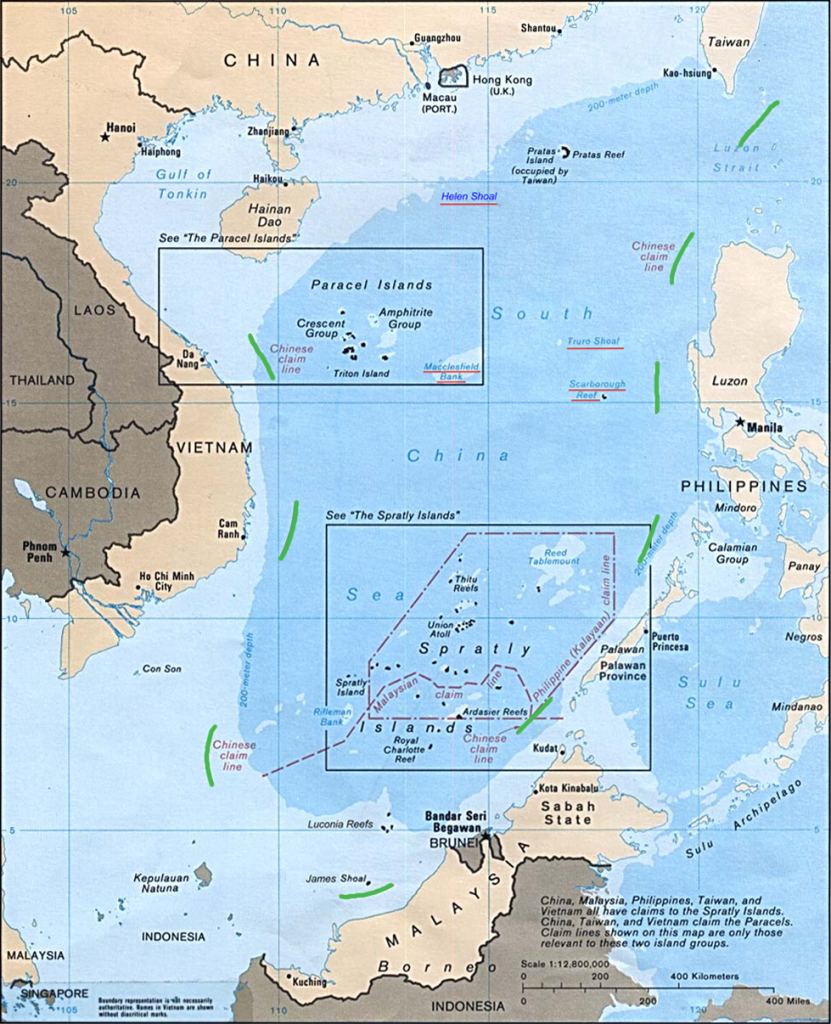

So what does supporting Manila’s arbitral filing suggest with regard to interpreting the Obama Administration’s position in the dispute? To figure that out comes down to determining what the Philippines is really asking the arbitral tribunal to do. Whereas the underlying tensions of the dispute relate to which State owns what island, Manila has cleverly requested that the tribunal restrict its judgment to something much more precise. Specifically, the arbitration request doesn’t ask the tribunal to determine ownership on a historical basis per se, but that it only clearly establish the sovereignty rights of the Philippines under UNCLOS due to the claimed non-island status of the reefs and shoals. The Philippines have requested the tribunal to:

a. declare that China’s rights in regard to maritime areas in the SCS, like the rights of the Philippines, are those established by UNCLOS;

b. declare that China’s maritime claims in the SCS based on its so-called “nine-dash line” are contrary to UNCLOS and invalid;

c. require China bring its domestic legislation into conformity with its obligations under UNCLOS;

d. declare that Mischief Reef and McKennan Reef are submerged features that form part of the Continental Shelf of the Philippines under Part VI of the Convention, and that China’s occupation of and construction activities on them violate the sovereign rights of the Philippines;

e. require that China end its occupation of and activities on Mischief Reef and McKennan Reef;

f. declare that Gaven Reef and Subi Reef are submerged features that are not above sea level at high tide, not islands under UNCLOS, not located on China’s Continental Shelf, and China’s occupation and construction activities on these features are unlawful;

g. require China to terminate its occupation of and activities on Gaven Reef and Subi Reef;

h. declare that Scarborough Shoal, Johnson Reef, Cuarteron Reef and Fiery Cross Reef are submerged features and are “rocks” under Article 121(3) of UNCLOS;

i. require that China refrain from preventing Philippine vessels from exploiting the living resources in the waters adjacent to Scarborough Shoal and Johnson Reef;

j. declare that the Philippines is entitled under UNCLOS to a 12nm territorial sea, a 200nm Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), and a Continental Shelf under UNCLOS, measured from its archipelagic baselines;

k. declare that China has unlawfully claimed, and has unlawfully exploited, the living ad non-living resources in the Philippines’ EEZ and Continental Shelf;

l. declare that China has unlawfully interfered with the exercise by the Philippines of its rights to navigation and other rights provided under UNCLOS;

m. require China desist from these unlawful activities.

Note: China has refused the arbitration request. Annex VII, Article 9 of UNCLOS, however, provides that “if one of the parties to the dispute does not appear before the arbitral tribunal or fails to defend its case, the other party may request the tribunal to continue the proceedings and to make its award. Absence of a party or failure of a party to defend its case shall not constitute a bar to the proceedings.”

Although the Philippines did not request that the tribunal resolve the sovereignty claims directly, it does ask it to determine a very significant issue: whether the disputed features are rocks or islands. In these instances, the Philippines believes determinations that they are not islands would further its aims. For even if China retained ownership it would minimize the extent of China’s territorial claims under international law. This is because under UNCLOS, rocks only get 12nm of territorial seas. Islands, however, get 12nm of territorial seas AND 200nm of an exclusive economic zone. This is why each and every island/rock matters and why there is so much at stake. It’s critical to remember that the fight is not over what is on the island/rock, but the resources in the water column and shelf surrounding the island/rock.

Turning back to the Obama Administration’s SCS strategy, Secretary Kerry’s statement may be interpreted in at least two-ways. The statement could suggest support of Manila’s sovereignty claims and therefore the U.S. would be taking sides. The statement could also suggest support of Manila’s right to argue their claims under international law and therefore the U.S. would be supporting a peaceful settlement of the dispute in an international forum rather than a regional one. Carpenter’s article does an excellent job of describing the potential implications if the U.S. strategy included choosing sides. On the other hand, if the U.S. is supporting Manila’s right to argue their claims under international law, the implications for the U.S. could be a loss of credibility. It continues to remain harmful for the United States, especially in the SCS context, to keep suggesting that this dispute ought to be settled under UNCLOS because the U.S., due to political reasons in the Senate, has yet to ratify this critical treaty.

LT Dennis Harbin is a qualified surface warfare officer and is currently enrolled at Penn State Law in the Navy’s Law Education Program. The opinions and views expressed in this post are his alone and are presented in his personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy. This article is for informational purposes only and not for the purpose of providing legal advice.

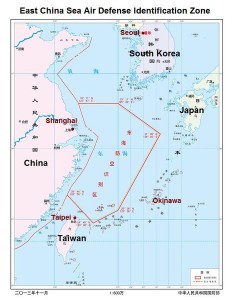

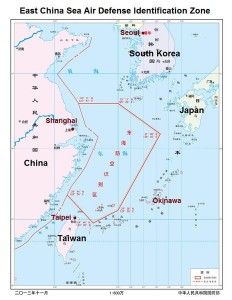

The big news of the day is China’s declaration of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over parts of the East China Sea, notably furthering the potential for conflict with Japan over the Senkakus/Diaoyus. Per guidelines released Saturday, the policy requires non-commercial aircraft in the space to pre-arrange flights with China’s government – effectively creating a pretense for action against Japanese military aircraft should they fail to comply with rules set for a space they likewise consider their own. Taiwan, which also maintains claims to islands it calls the Tiaoyutai, has voiced regret over the move.

The big news of the day is China’s declaration of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over parts of the East China Sea, notably furthering the potential for conflict with Japan over the Senkakus/Diaoyus. Per guidelines released Saturday, the policy requires non-commercial aircraft in the space to pre-arrange flights with China’s government – effectively creating a pretense for action against Japanese military aircraft should they fail to comply with rules set for a space they likewise consider their own. Taiwan, which also maintains claims to islands it calls the Tiaoyutai, has voiced regret over the move.