By Alex Calvo

This is the third installment in a five-part series summarizing and commenting the 5 December 2014 US Department of State “Limits in the Seas” issue explaining the different ways in which one may interpret Chinese maritime claims in the South China Sea. It is a long-standing US policy to try to get China to frame her maritime claims in terms of UNCLOS. Read part one, part two.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

Let us move to the three interpretations put forward by the US Department of State.

1.- “Dashed Line as Claim to Islands”

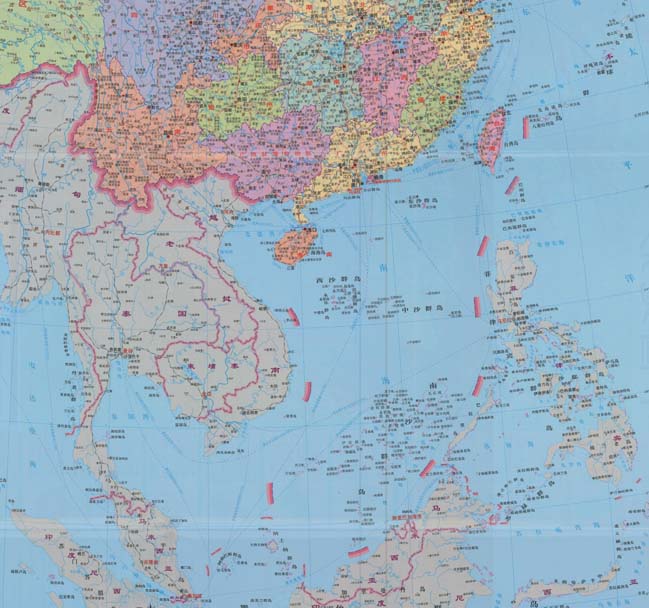

This would mean that all Beijing was claiming were the islands within the dashed lines, and that any resulting maritime spaces would be restricted to those recognized under UNCLOS and arising from Chinese sovereignty over these islands. The text notes that “It is not unusual to draw lines at sea on a map as an efficient and practical means to identify a group of islands”. In support of this interpretation one could take the map attached to the 2009 Notes Verbales and the accompanying text, which reads “China has indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters, and enjoys sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the relevant waters as well as the seabed and subsoil thereof (see attached map)”. The text notes that the references in the paragraph above to “sovereignty” over “adjacent” waters” may be interpreted as referring to a 12-nm belt of territorial sea, since international law recognizes territorial waters as being a sovereignty zone. In a similar vein, references to “sovereign rights and jurisdiction”, “relevant waters”, and “seabed and subsoil thereof”, would then be taken to concern the legal regime of the EEZ and the continental shelf, as defined by UNCLOS.

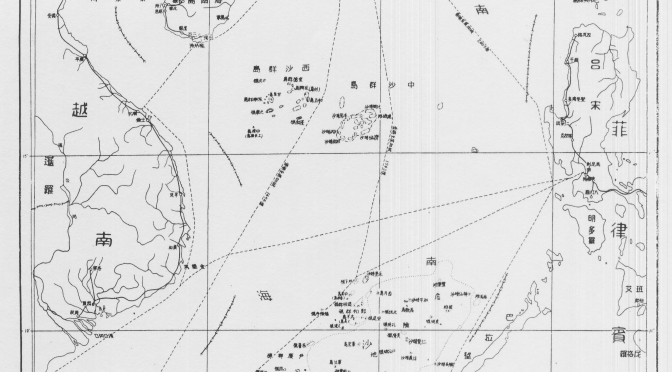

As possible evidence for this interpretation, the study cites some Chinese legislation, cartography, and statements. The former includes Article 2 of the 1992 territorial sea law, which claims a 12-nm territorial sea belt around the “Dongsha [Pratas] Islands, Xisha [Paracel] Islands, Nansha (Spratly) Islands and other islands that belong to the People’s Republic of China”. This article reads “The PRC’s territorial sea refers to the waters adjacent to its territorial land. The PRC’s territorial land includes the mainland and its offshore islands, Taiwan and the various affiliated islands including Diaoyu Island, Penghu Islands, Dongsha Islands, Xisha Islands, Nansha (Spratly) Islands and other islands that belong to the People’s Republic of China. The PRC’s internal waters refer to the waters along the baseline of the territorial sea facing the land”. The Department of State also stresses that China’s 2011 Note Verbale states that “China’s Nansha Islands is fully entitled to Territorial Sea, Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), and Continental Shelf”, without laying down any other maritime claim. Concerning cartography, the study cites as an example the title of “the original 1930s dashed-line map, on which subsequent dashed-line maps were based”, which reads, “Map of the Chinese Islands in the South China Sea” (emphasis in the DOS study). With regard to Chinese statements, the study cites the country’s 1958 declaration on her territorial sea, which reads “and all other islands belonging to China which are separated from the mainland and its coastal islands by the high seas” (emphasis in the DOS study). The text argues that this reference to “high seas” means that China could not be claiming the entirety of the South China Sea, since should that have been the case there would have been no international waters between the Chinese mainland and her different islands in the region. This is a conclusion with which it is difficult to disagree, although we should not forget that it was 1958, with China having barely more than a coastal force rather than the present growing navy. Therefore, while the study’s conclusion seems correct, and precedent is indeed important in international law, it is also common to see countries change their stance as their relative power and capabilities evolve. Thus, if China had declared the whole of the South China Sea to be her national territory in 1958 this would have amounted to little more than wishful thinking, given among others the soon to expand US naval presence in the region and extensive basing arrangements. Now, 50 years later, with China developing a blue water navy, and the regional balance of power having evolved despite the US retaining a significant presence, Beijing can harbor greater ambitions.

This section ends with the DOS study stating that should this interpretation be correct, then “the maritime claims provided for in China’s domestic laws could generally be interpreted to be consistent with the international law of the sea”. This is subject to two caveats, territorial claims by other coastal states over these islands, and Chinese ambiguity concerning the nature of certain geographical features, Beijing not having “clarified which features in the South China Sea it considers to be ‘islands’ (or, alternatively, submerged features) and also which, if any, ‘islands’ it considers to be ‘rocks’ that are not entitled to an EEZ or a continental shelf under paragraph 3 of Article 121 of the LOS Convention”. Some of these features, Scarborough Reef for example, are part of the arbitration proceedings initiated by the Philippines.

2.- “Dashed Line as a National Boundary”

This would mean that Beijing’s intention with the dashed line was to “indicate a national boundary between China and neighboring States”. As supporting evidence for this interpretation, the DOS report explains that “modern Chinese maps and atlases use a boundary symbol to depict the dashed line in the South China Sea”, adding that “the symbology on Chinese maps for land boundaries is the same as the symbology used for the dashes”. Map legends translate boundary symbols as “either ‘national boundary’ or ‘international boundary’ (国界, romanized as guojie)”. Chinese maps also employ “another boundary symbol, which is translated as ‘undefined’ national or international boundary (未定国界, weiding guojie)” but this is never employed for the dashed line.

The report stresses that, under international law, maritime boundaries must be laid down “by agreement (or judicial decision) between neighboring States”, unilateral determination not being acceptable. The text also notes that the “dashes also lack other important hallmarks of a maritime boundary, such as a published list of geographic coordinates and a continuous, unbroken line that separates the maritime space of two countries”. The latter is indeed a noteworthy point, since border lines would indeed seem to need to be continuous by their very nature, rather than just be made up of a number of dashes. This is one of the aspects making it difficult to fit Beijing’s claims with existing categories in the law of the sea. In addition, the report notes that they cannot be a limit to Chinese territorial waters, since they extend beyond 12 nautical miles, and neither can they be a claim to an EEZ, since “dashes 2, 3, and 8” are “beyond 200 nm from any Chinese-claimed land feature”. These last two aspects also make it difficult to see the dashed line as marking one of the categories recognized by UNCLOS. Moving beyond the law, however, and this is something that the DOS report does not address, a certain degree of ambiguity may be seen as beneficial by a state seeking to gradually secure a given maritime territory. Some voices have noted this may have been the US calculus in the San Francisco Treaty. Thus, the technical faults, from an international legal perspective, in China’s dotted line are not necessarily an obstacle to Beijing’s claims, from a practical perspective.

Read the next installment here.

Alex Calvo is a guest professor at Nagoya University (Japan) focusing on security and defence policy, international law, and military history in the Indian-Pacific Ocean. Region. A member of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC) and Taiwan’s South China Sea Think-Tank, he is currently writing a book about Asia’s role and contribution to the Allied victory in the Great War. He tweets @Alex__Calvo and his work can be found here.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]