The following article originally appeared in The Naval War College Review and is republished with permission. Read it in its original form here. It will be republished in three parts, read Part One here.

By Christofer Waldenström

The Field of Sensors

To determine whether the field of safe travel is receding toward the minimum safety zone, the commander must be able to observe the objects present in the naval battlefield. Today, the naval battlefield comprises more than just the surface of the sea. Threats of all sorts can come from either beneath the surface or above it. The driver of a car determines from the pertinent visual field whether the field of safe travel is receding toward the minimum stopping zone.22 For a commander, however, it is not possible to perceive directly the elements of the operations area—the naval battlefields are far too vast. Instead, as noted above, the objects present have to be inferred, on the basis of sensor data.23

Thus, there exists a “field of sensors” that the commander uses to establish whether the field of safe travel approaches the edge of the minimum safety zone. The field of sensors is an objective spatial field the boundaries of which are determined by the union of the coverage of all sensors that provide data to the commander. The importance of the sensor field is also emphasized in one theory of perception-based tactics that has been advanced (though without discussion of its spatial dimensions).24 As the sensors that build up the field have different capabilities to detect and classify objects, the field of sensors will consequently consist of regions in which objects can be, variously, detected and classified with varying reliability. (These regions could be seen as fields in their own right, but for now we will leave them as is.) Nevertheless, to establish the boundary of the field of safe travel and determine whether it is receding toward the minimum safety zone, the commander must organize the field of sensors in such way that it is possible both to detect contacts and to classify them as nonhostile before they get inside the minimum safety zone.

Factors Limiting Detection

Several factors limit the detection of enemy units. First, terrain features can provide cover. Units that hide close to islands are difficult to detect with radar. In a similar way, a submarine that lies quietly on the bottom is difficult to distinguish from a rock formation with sonar. The weather is another factor: high waves make small targets difficult to detect; fog and rain reduce visibility for several sensors, such as visual, infrared, and radar; and temperature differences between layers in the atmosphere and in the water column influence how far sensors can see or hear. Yet another factor is stealth, or camouflage, whereby units are purposely designed to be difficult to detect with sensors. Sharp edges on a ship’s hull reflect radar waves in such ways that they do not return to the transmitting radar in detectable strength. Units are painted to blend into the background, propulsion systems are made silent, ships’ magnetic fields are neutralized, and exhaust gases are cooled—all to reduce the risk of detection. Being aware of these factors makes it possible for commanders to use them to advantage. Units might be positioned close to islands while protecting the field of safe travel, or the high-value units might select a route that will force the enemy units to move out at sea, thus making themselves possible to detect.

Factors Limiting Classification

To avoid being classified, the basic rule is to not emit signals that allow the enemy to distinguish a unit from other contacts around it. Often naval operations are conducted in areas where neutral or civilian vessels are present, and this makes it difficult to tell which contacts are hostile. To complicate matters, the enemy can take advantage of this. For example, an enemy unit can move in radar silence in normal shipping lanes and mimic the behavior of merchants, so as to be difficult to detect using radar and electronic support measures. Suppressing emissions, however, only works until the unit comes inside the range where the force commander would expect electronic support measures to classify its radar—no merchant ever travels radar silent. To detect potential threats the commander establishes a “picture” of the normal activities in the operations area. Behavior that deviates from the normal picture is suspect and will be monitored more closely. Thus, contacts that behave as other contacts do will be more difficult to classify.

The Field of Weapons

As mentioned above, the commander has three choices for handling a detected threat: move the high-value units away from the threat, take action to eliminate the threat, or receive the attack and defend. In the two latter cases the threat can be eliminated either by disabling it or by forcing it to retreat. Either way, the commander must have a weapon that can reach the target with the capability to harm it sufficiently. It is immaterial what type of weapon it is or from where it is launched, as long as it reaches the target and harms it sufficiently. Thus, the weapons carried by the commander’s subordinate units, or any other unit from which the commander can request fire support, create a “field of weapons” in which targets can be engaged. Like the field of sensors, the field of weapons is a spatial field, bounded by the union of the maximum weapon ranges carried by all units at the commander’s disposal. The field of weapons is further built up by the variety of weapons, which means that the field consists of different regions capable of handling different targets. For example, there will be regions capable of engaging large surface ships, regions capable of destroying antiship missiles, and other regions capable of handling submarines. Nevertheless, to prevent the high-value units from being sunk, the field of weapons must be organized in such way that it is possible to take action against hostile units and missiles before they get inside their corresponding minimum safety zones. For example, the threat posed by air-to-surface missiles can be dealt with by protecting two minimum safety zones. The commander can take out the enemy aircraft before they get a chance to launch the missile—that is, shoot down the aircraft before they enter the minimum safety zone created by the range of the missile they carry. If this fails the commander can take down the missiles before they hit the high-value units—that is, shoot down the missiles before they get inside the minimum safety zone created by the distance at which the missile can do damage to the high-value units.

It is now possible to specify how the fields of sensors and weapons work together: the field of sensors and the field of weapons must be organized in such a way that for each field of safe travel hostile units can be detected, classified, and neutralized before they enter the corresponding minimum safety zone. One scholar of naval tactics and scouting touches on what can serve as an illustration. Closest to the ships that should be protected is a zone of control where all enemies must be destroyed; outside the zone of control is a zone of influence or competition, something like a no-man’s-land.25 Outside the zone of influence is a zone of interest where one must be prepared against a detected enemy. Scouting in the first region seeks to target; in the second, to track; and in the third, to detect. Important to notice is that the field of sensors and the field of weapons are carried by, tied to, the commander’s units, which simultaneously bring the fields to bear with respect to all pairs of fields of safe travel and minimum safety zones. This complicates matters for the commander. As the fields of safe travel and minimum safety zones are stacked, actions taken to tackle a threat to one minimum safety zone may create problems for another. The competition of units between the pairs of minimum safety zones and fields of safe travel may lead to a situation where a managed air-warfare problem creates a subsurface problem. This bedevilment is not unknown to the naval warfare community: “The tactical commander is not playing three games of simultaneous chess; he is playing one game on three boards with pieces that may jump from one board to another.”26

To illustrate the problem, suppose that the situations in figure 3 occur simultaneously; there is both a surface and a subsurface threat to the high-value unit. In this case the field of sensors has to be organized so that contacts can be detected and classified in a circular field with a radius of a hundred kilometers (for the antiship missile, figure 3a) and also within a smaller and elliptical field (figure 3b, in the torpedo case). For example, radars and electronic support measures have to be deployed to detect and identify surface contacts, while sonar and magneticanomaly detection have to be used to secure the subsurface field. Accordingly, the field of weapons has to be organized so that contacts can be engaged before entering the respective minimum safety zones—antisubmarine weapons for subsurface threats and antiship weapons for surface threats.

Not only weapons can be used to shape the field of safe travel; another means to influence it is deception. Deception takes advantage of the inertia inherent in naval warfare. First, there is the physical inertia whereby a successful deception draws enemy forces away from an area, giving an opportunity to act in that area before the enemy can move back. Second, there is the cognitive inertia of the enemy commander. It takes some time before the deception is detected, which gives further time. Deception can, thus, be seen as a deliberate action within the enemy’s field of sensors to shape the field of safe travel to one’s own advantage. For successful deception it is necessary that commanders understand how their own actions will be picked up by the enemy’s field of sensors and that they be aware of both the enemy’s cognitive and physical inertia. The commander has to “play up” a plausible scenario in the enemy’s field of sensors and then give the enemy commander time to decide that action is needed to counter that scenario (cognitive inertia) and then further time to allow the enemy units to move in the wrong direction (physical inertia). The central role of inertia will be further discussed later.

Having defined the fundamental fields it is now possible to formulate what is required from commanders to establish sea control. The skill of securing control at sea consists largely in organizing a requisite set of pairs of correctly bounded minimum safety zones and corresponding fields of safe travel shaped to counter actual and potential threats, and in organizing the field of sensors and field of weapons in such way that that for each field of safe travel, hostile contacts can be detected, classified, and neutralized before they enter the corresponding minimum safety zone.

Factors Limiting the Field of Safe Travel

So far it has been said that it is the enemy that limits and shapes the field of safe travel. This is, however, not the whole truth. The field of safe travel is also shaped by other physical and psychological factors.

Terrain Features That Reduce Capability to Detect and Engage Targets

To be able to sink the high-value unit the enemy must detect, classify, and fire a weapon against it. All this must happen in rapid succession, or the high-value unit may slip out of the weapon’s kill zone. This means that to fire a weapon against the high-value unit the enemy must organize its field of sensors and its field of weapons so that they overlap the high-value unit at the time of weapon release. In this way the field of safe travel is built up by all the paths that take the high-value unit outside the intersection of the enemy’s field of sensors and the enemy’s field of weapons. This further means that the boundaries of the field of safe travel are determined in part by terrain regions where high-value units can go but enemy weapons cannot engage them—for example, an archipelago that provides protection against radar-guided missiles. The boundaries are also determined by the enemy’s capability to detect the high-value units, and thus terrain features can also delimit the field of safe travel in that they protect the high-value units from detection. For example, the archipelago mentioned above also provides protection against detection by helicopter-borne radar, as long as the ships move slowly. (If they start to move quickly, however, they will stand out from the clutter of islands.) It is also important to notice that a minimum safety zone is resized in the same way as the corresponding field of safe travel—if the enemy cannot see the high-value unit or has no weapon that can engage it, the enemy unit can be allowed closer in.

Terrain Regions Where Enemy Units Can Hide

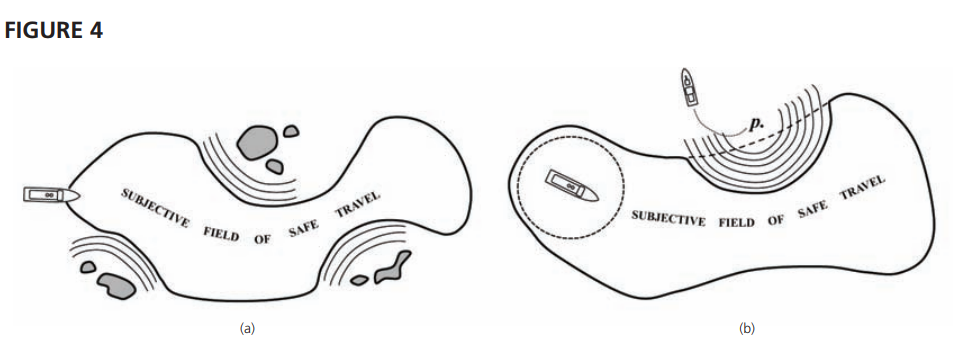

Like enemy units, potential threats also throw out lines of clearance. One such potential threat is a terrain feature where the enemy might have concealed units and from which attacks can be launched (see figure 4a). Such regions—for example, islands where enemy units can hide close to land—contain potential threats. There may or may not be actual threats there, the objective field of safe travel may or may not be clear, but since commanders can only react to their subjective fields, the latter are properly shaped and limited by these barriers.

Enemy Units That Are Spotted and Then Lost

Another potential threat that will radiate clearance lines arises from the movement of enemy units. It is possible for a contact that has been detected and classified to slip out of the field of sensors —for instance, by turning off its radar after being tracked by electronic support measures. The potential movement of such a unit shapes the field of safe travel. Suppose an enemy unit was detected at position p at time t (see figure 4b). As the enemy is outside the field of safe travel, it does not pose a threat to the commander at this time. Now, the contact slips out of the field of sensors, and contact with it is lost. As time passes and the commander fails to reestablish contact, the region where the unit can be is a circle that grows proportionally to the maximum speed of the enemy unit. Eventually the region grows to such a size that it is not possible for the force to pass without the minimum safety zone intersecting with it. In figure 4b the subjective field of safe travel is correctly shaped by the potential threat, but the objective field of safe travel is clear—the enemy unit has turned around and is heading away.

Legal Obstacles and Taboos

The field of safe travel is also limited by international law. One such legal obstacle is the sea territory of neutral states. A neutral state has declared itself outside the conflict the commander is involved in, and this prohibits the parties of the conflict from using its sea territory for purposes of warfare. Such regions delimit the fields of safe travel and thus restrict where the commander’s units can move. On the other hand, they do not pose a threat to the high-value units and can safely be allowed to encroach on the minimum safety zone.

Neutral Units in the Operations Area

Today, as noted, naval operations take place in areas where neutral shipping is present. Like the sea territory of neutral states, neutral shipping is protected by international law. A consequence of this is that neutral shipping in the area also influences the shape of the field of safe travel. The commander is of course prohibited from attacking neutral merchants. This is not a problem in itself—if a certain contact is classified as neutral, we cannot engage it. Nevertheless, it has implications for where high-value units are allowed to move. As neutral shipping cannot be engaged, we are forbidden to use it for cover—for instance, to move so close to a merchant vessel as to make it difficult for the opponent to engage without risk of sinking the merchant. This means that neutral shipping creates “holes” in the field, where combatants are not allowed to move. If the commander does not track the merchant vessels continuously, these holes grow proportionally to the merchants’ maximum speed, as they do for enemy units spotted and then lost.

Mines

Mines shape the field in the same way that ships do. They can be seen as stationary ships with limited weapon ranges; the minimum safety zone for a mine would be the range at which a ship could pass it without being damaged if the mine detonated. Laying mines shapes the commander’s field, and the commander must react, either by taking another route or by actively reshaping the field—that is, by clearing the mines. Clearing mines has the same effect as taking out enemy ships; the field of safe travel expands into the area that has been cleared. Of course, the enemy can use this for purposes of deception, pretending to lay mines, sending a unit zigzagging through a strait, and making sure that the commander’s field of sensors picks this up. If the deception is successful, the commander’s subjective field is shaped incorrectly.

Dr. Waldenström works at the Institution of War Studies at the Swedish National Defence College. He is an officer in the Swedish Navy and holds an MSc in computer science and a PhD in computer and systems sciences. His dissertation focused on human factors in command and control and investigated a support system for naval warfare tasks. Currently he is working as lead scientist at the school’s war-gaming section, and his research focuses on learning aspects of war games.

References

22. Gibson and Crooks, “Theoretical FieldAnalysis of Automobile-Driving,” p. 457.

23. Intelligence reports from higher command are also included when constructing this operational view of the battlefield. This operational view of the battlefield is compiled by exchanging and merging sensor data, a partly manual and partly automatic process well known in all navies. The result is usually displayed as a map of the operations area overlaid with symbols representing the objects present in varying stages of classification— detected, classified, or identified.

24. T. Taylor, “A Basis for Tactical Thought,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings (June 1982).

25. Hughes, Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat.

26. Ibid., p. 196.

Featured Image: MEDITERRANEAN SEA (July 25, 2012) A plane captain signals to the pilot of an F/A-18C Hornet assigned to the Blue Blasters of Strike Fighter Squadron (VFA) 34 on the flight deck of the Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN 72). (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist Seaman Joshua E. Walters/Released)