The following piece by guest author Michael E. Lambert is from our partners at the CDA Institute as part of an ongoing content-sharing relationship. You can read the article in its original form here.

Military cooperation between Northern European countries has been difficult to implement, especially because of diverging interests among countries bordering the Baltic Sea. This unique space includes Russia and its military outpost located in the oblast of Kaliningrad, NATO members that remain outside the European Union (Norway), members of the European Union outside of NATO (Sweden and Finland), and finally both NATO and EU member countries (Denmark, Germany, Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania).

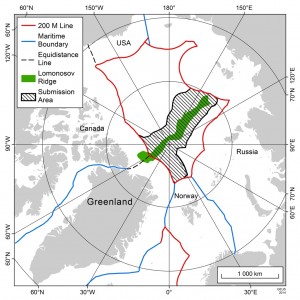

With the recent claim by Moscow to the United Nations of 1.2 million square kilometres of territory located on the Arctic sea shelf, and suspicion of getting ready for another hybrid war in Estonia, the Nordic Defence Cooperation (NORDEFCO) arrangement seems more essential than ever to thwart Russian ambitions on the Continent.

From a historical perspective, cooperation between countries in Northern Europe has always been problematic, due to the fragmentation of interests and resources committed to their respective militaries. Countries such as Sweden still claim a policy of neutrality, while seeing Finland as a buffer zone between Stockholm and Moscow. On its side, Finland has long been opposed to NATO membership, owing to continuing fear of reprisals from Russia, with which it shares a common border.

Norway still refuses to consider integration in the European Union, in order to continue to reap substantial profits by selling its oil to the EU, and sales profits are used to modernize its army. Norway therefore shows a higher military level compared to other Scandinavian countries, evidenced by the proposed acquisition of the Lockheed Martin F-35 fifth-generation aircraft, while countries like Finland attempt to optimize their smaller military budgets by exploring other options, like the Eurofighter or the Saab Gripen fourth-generation aircrafts.

These differences of equipment impede interoperability between Nordics. Also, identity is today one of the obstacle to ensure reliable safety against Moscow. For instance, Nordic countries are keen to become leaders in the field of cyber-defence, but NORDEFCO has always denied the participation of Estonia, which is the most advanced country in this field owing to its NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence in Tallinn. Although Estonia has many of the characteristics of a Nordic country, its candidacy was never taken seriously because of its occupation by the Soviet Union until 1991.

These issues explain the late launch of NORDEFCO in 2009, and even if the cooperation is presented as a way to improve security on the long run, the implementation is not so obvious and discussions still remain theoretical.

To date, it is unclear what would happen in case of potential Russian aggression. Indeed, the differences between all the countries in the North seem to be now a real issue. As an example, Finland may end up isolated due to its policy of neutrality. And NATO won’t be able to provide a coercive response by using the Article 5 of the Washington Treaty, in so far as Finland doesn’t realize that neutrality may no longer be the best option. Moreover, the refusal to include Estonia leaves Tallinn isolated vis-à-vis Finland, at a critical time when NATO has yet to find a way to counter hybrid warfare strategies.

In a rather paradoxical way, the launch of the NORDEFCO was presented as a way to enhance cooperation between countries with similar cultures and to build partnerships in the military-industrial sector. But this theoretical vision is now facing financial reality, as reflected by the military equipment acquisitions planned for the Royal Norwegian Air Force compared to that of the Finnish Air Force.

Moreover, the rejection of Estonia from “Northern Europe” shows a certain narrow-mindedness and lack of pragmatism in relation to the threat posed by Russia.

Like the current situation in the European Union, the lack of willingness to emerge as a single military power seems to be the biggest obstacle for Northern European military cooperation, abetted by their divergent national interests. Countries in the Northern part of Europe have the capabilities to give rise to the type of regional cooperation needed in the current crisis with the Kremlin, but have failed to develop a common vision despite their otherwise strong similarities.

Michael E. Lambert is a PhD student at the Sorbonne Doctoral College & University of Tampere, currently working at the French Ministry of Defence – IRSEM and Franco-German Institute on soft and smart power issues.