The following is part of Dead Ends Week at CIMSEC, where we pick apart past experiments and initiatives in the hopes of learning something from those that just didn’t quite pan out. See the rest of the posts here.

Dead ends aren’t always failures of the innovation. Sometimes good ideas are drowned by bureaucracies. In the 1994 paper “The Politics of Naval Innovation” released through the Center for Naval Warfare Studies at the Naval War College, contributor Jeffery Sands states that military organizations are large, conservative, and hierarchical. Resistance exists because: 1) the free flow of information is restricted in hierarchical organizations; 2) leaders have no interest in encouraging their own obsolescence by introducing innovations; and 3) organizations such as the Navy, which are infrastructure-intensive and where changes to that infrastructure are both expensive and lengthy, need some modicum of stability.

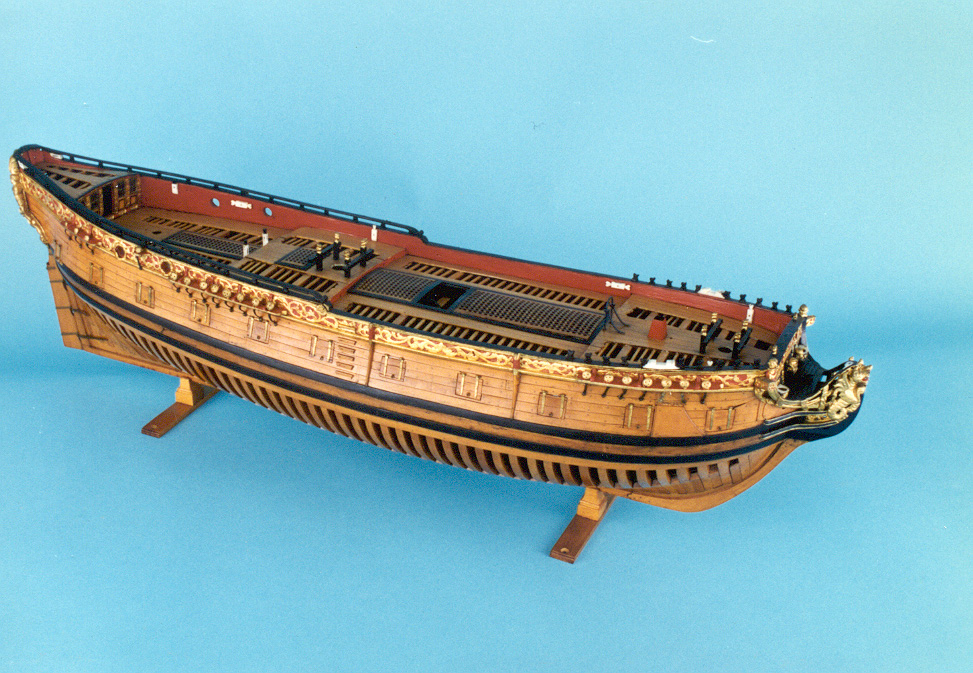

The failure of leadership to innovate can be found through two nameless British dockyard models from the Henry Huddleston Rogers Collection at the United States Naval Academy Museum, which has the second largest collection of dockyard models outside of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England.

The model pictured at right is a Royal Navy Board hull model of a three-masted, 24-gun Sixth Rate with a pinched (or “pink”) stern, a design not seen in any other known age-of-sail model. The sterns of most English rated warships of the 17th and 18th centuries were burdened by heavy, overhanging square sterns and quarter galleries attached to the hull only at the ends and supported by a series of horizontal transoms. This made the ship difficult to maneuver, particularly in following seas, much like a small car towing a U-Haul in windy conditions. The stern was, of course, where the cabins were located for the captain and, in larger ships of the line, an admiral.

The pinched stern arrangement transferred the weight of the stern on vertical timbers that were taken down to the keel. That made the stern much sturdier. The designer proposed this innovative ship to improve the ship’s maneuverability, survivability, and speed advantages in a fight. The design would, however, have eliminated the precious cabin space for the senior officers. Although two pink stern hulls were eventually built, the Admiralty demonstrated its resistance to this innovative design simply because of the loss of their comfort and cabin space.

HRR Model No. 14

In the 1984 mock rockumenatory “This is Spinal Tap,” lead guitarist (portrayed by Christopher Guest) explains to the interviewer that his amps “go to eleven” because they’re “one louder.” The interviewer asks him why he doesn’t just adjust the amps so that “ten” is louder. The perplexed Tufnel pauses for a moment and then simply reiterates: “These go to eleven.” The similar befuddled intransigence to a naval modification is exhibited in HRR Model No. 14, an English Fifth Rate 32-Gun ship.

The ship was proposed in 1689 or 1690. British ships of that period fell into one of three classes: ships-of-the-line generally with three decks of guns, frigates with two gun decks, and smaller ships with one gun deck. Model No. 14 is the grandfather of what became the true British frigates in the late 18th century.

Arthur Herbert, Earl of Torrington (incidentally the first person to use the term “fleet in being”), was a battle-scarred veteran of the Dutch Wars and realized that the Royal Navy needed large numbers of a new kind of robust and maneuverable cruiser capable of remaining at sea for long periods of time. To be truly effective, they should be able to employ their main battery of guns even in regions of rougher weather since heavy guns on the lower deck were normally too near the waterline to be used in battle except in optimal weather conditions. The original concept was that the lower deck was to be left completely unarmed without any gunports. The Admiralty board balked. The debate likely went something like this:

Torrington: “We’ve improved the design by having the guns on the upper deck.”

Admiralty: “But a frigate has two gundecks.”

Torrington: “Yes, but by having all the guns on the upperdeck she has better seakeeping.”

Admiralty: “But a frigate has two gundecks.”

(Fast forward as Torrington modifies the dockyard model to add one small gunport on each side of the stern pictured below.)

Torrington: “Here’s your second gundeck.”

Admiralty: “Ah, a frigate has two gundecks! Well done!”

This evolution became symptomatic of the British for the next century to build light originally but then modify the ships with more guns than for which they were originally designed. Ultimately it would be another century before the Admiralty adopted a frigate that had a seven-foot freeboard as the standard.

Claude Berube is the Director of the Naval Academy Museum and instructor in the Department of History. He is the author of several books and more than forty articles. The author notes the extensive research on the dockyard models done by specialist Grant Walker at the Naval Academy Museum.