Sea Control discusses the Baltic perception – specifically Swedish – of the Russian threat with Aaron Korewa and Katarina Tracz. This is the first of several future podcasts with our friends from Sweden.

Sea Control discusses the Baltic perception – specifically Swedish – of the Russian threat with Aaron Korewa and Katarina Tracz. This is the first of several future podcasts with our friends from Sweden.

Tag Archives: Poland

Ukraine: Sink or Swim

Ще не вмерла України і слава, і воля

Ukraine has not yet perished, nor her glory, nor her freedom

Upon us, fellow Ukrainians, fate shall smile once again.

These words of the Ukrainian National Anthem are full of passion, but they are a key to understanding the dynamics of the events and determination in Kiev. What pushed thousands of people to remain in Majdan Square for 3 winter months in spite of more than 70 victims? Clausewitz’s trinity of passion, chance, and reason is in some way applicable to today’s situation in Ukraine. There is clearly passion, and chance was evident in that this was the second opportunity for revolution – the first being the Orange revolution of 2004-2005. Now reason must govern a way forward full of compromises. For those in the U.S. public who would like to be more informed about these events, a series of questions arises:

– What Happened and Why?

– What Comes Next?

– What is the Larger Meaning for U.S. Interests and Strategy?

The direct cause of the protest was President Yanukovich’s rejection of the European Union Association Agreement. Aleksander Kwasniewski, former president of Poland, said that protests were predictable as one half of Ukraine wants to join the EU and the other half was persuaded by Yanukovich for three years that the agreement should be signed. So nearly everyone was surprised when the agreement was discarded.

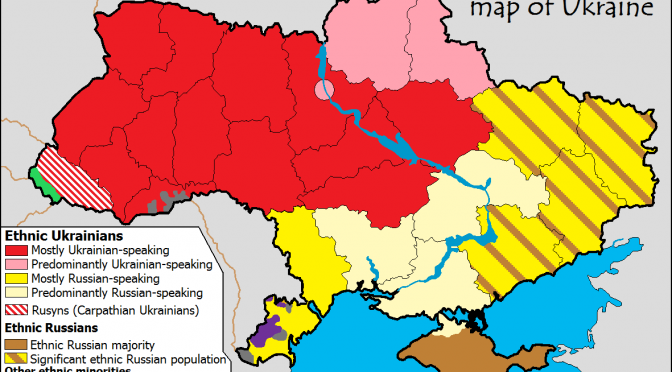

Commenters often talk about two parts of Ukraine that are very different. This is true, there is a difference in culture, religion, and business preferences, which comes from history. But both parts want to live in independent Ukraine, without neighbors interfering in domestic matters, and they want to have a chance to realize their ambitions. For many of us this sounds natural, sentimental, or simply trivial. This is a very old nation but very young state. Ukraine gained independence for a brief period between 1918 and 1920 and most recently again in 1991. Not surprisingly they are very sensitive to problems of national independence. Nationalism is strong and could be equally constructive or destructive. The fact that Ukraine was and continues to be very important to Russia, doesn’t help. And it makes a difference. We speak about the vital interests of a former hegemon and a country that has the ambition to regain its status as a world-class power.

So what comes next? We should start with the simple statement that the situation is unpredictable and volatile. There are at least two reasons for that. One is the pace of change and dynamic course of action, full of unexpected turns. Using an analogy to Boyd’s OODA Loop, Majdan acts inside the decision loop of any potential opponent. The second reason is that given the history of the country and the very short period of independence, Ukraine needs time to work on the many soft elements constituting a state: well-crafted law and respect for the rule of it, transparency, accountability, democratic traditions, mature political elites, and so on. This alone is challenging without speaking of external circumstances. The biggest and most immediate threat to Ukraine’s stability is the legitimization of the new President and the economic situation. Such arguments have already been raised by Russian Federation officials, according to Reuters:

“We do not understand what is going on there. There is a real threat to our interests and to the lives of our citizens,” Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev was quoted by Russian news agencies as saying.

“There are big doubts about the legitimacy of a whole series of organs of power that are now functioning there.”

Strong rhetoric is not a mere ghost from the past. It is a sign that other tools from the Soviet epoch could also find their way into the hands of state leaders. We could witness subtle diplomacy interweaving with hard politics. The references to Russian citizens are especially worrisome. It seems natural, but we shouldn’t forget that there is a strong ethnic Russian minority in Crimea [who reportedly “elected” a Russian citizen as mayor this week] and that Sevastopol is a major naval base for Black Sea Fleet. The situation seems to be serious enough to cause a series of public statements by officials from both the United States and Poland.

Bronisław Komorowski, President of Poland considers honest and transparent presidential elections, producing an undeniable outcome, as a top priority. This was quickly countered by Russian Federation Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov, who stated, “We consider it premature to hold presidential elections in Ukraine in May, as it contradicts the agreement dated February 21.”

On Feb 23rd, the U.S. State Department on Twitter said “US expects Ukraine’s sovereignty, territorial integrity, democratic freedom of choice to be respected by all states”.

Prof. Stanislaw Koziej, Chief of BBN (Poland’s National Security Counsel) expressed his concern more directly: “Intervention in Ukraine by foreign power would have significant consequences for international security”.

In order to facilitate strategy shaping for dealing with Ukraine, Prof. Zbigniew Brzezinski offers his long-term vision in an article titled “Ukraine Should Join EU, but No Military Alliance” and says “In brief, the Finnish model is the ideal example for Ukraine, and the EU, and Russia.”

From the geo-strategic point of view, the big problem is that any formal or institutional link of Ukraine with the EU drastically limits Russia’s options and potential to influence this country.

What does this mean for the United States? Even if it doesn’t seem to be a priority, Ukraine’s future could have many indirect and strategic consequences. If the United States really believes in its values, it needs to respect the sovereign decision of Ukrainians. However, any chance of a scenario in which a weak Ukraine becomes a satellite state to Russia, would certainly resonate in all of Central Europe. That means adapting strategy, military modernization programs, and priorities at the NATO Summit in Wales, UK. A Strong or stronger Russia in this region is also an argument in favor of the “Three-Hub Navy” proposed by Brian McGrath.

But even then the hub in the Mediterranean still wouldn’t be among the top strategic priorities until we will assume that a powerful Russian Federation is a link between Europe and Asia. Russia is absent from most discussions about the Rebalance to the Pacific or events in China’s Near Seas, perhaps because the focus is on South China Sea. The way the Russian Federation is going to protect their interests in the Far East and Arctic, and interact with major players there, is likely to impact perceptions of security at least in Central Europe if not in the whole of Europe.

Any discussion about the future of Ukraine is impossible without considering the broader context in which Russia plays a key role. It has been this way for centuries. Poland is ready to offer its own experiences with the transformation process, which was long and painful, but the U.S. is probably the only power capable to persuade an assertive Russia.

Przemek Krajewski alias Viribus Unitis is a blogger In Poland. His area of interest is the context, purpose, and structure of navies – and promoting discussion on these subjects in his country.

Poland’s New Year Defense Resolutions

Tomasz Siemoniak, Poland’s Minister of Defense, was asked by the Polish web site “All the Essentials” what he considers the key ideas for 2014. This made for a very short list, but there are some interesting details. The main points he raised are:

Tomasz Siemoniak, Poland’s Minister of Defense, was asked by the Polish web site “All the Essentials” what he considers the key ideas for 2014. This made for a very short list, but there are some interesting details. The main points he raised are:

1. Still the United States! Despite many talking about the decline of American power and influence, Mr. Siemoniak believes this view premature and that Washington will remain a center for setting global security trends. He adds, however: “hopefully without further pivots and resets.” To be sure, U.S. presence in Europe remains crucial for Poland.

2. Cyber Defense. Siemoniak’s observations that effective cyberattacks can send victims directly to the Stone Age are not without a sense of humor. But that is perhaps the right tool in what he believes necessary-raising awareness among decision makers, the military, the press, and ordinary citizens. The storm caused by Snowden resulted in Sea State 1 in Poland. “Hard compromises between security and privacy are unavoidable.”

3. How Many Divisions? The message is that we need to diverge from the old paradigm of troop numbers, equipment, and the talents of commanders in determining the robustness of a state’s security. The economy, culture attractiveness, energy resources, and “even people ready to defend on Twitter our arguments in English or Russian” are important ingredients of a country potential.

4. Polish Fangs. This literary expression describes a shift in Poland’s security strategy that occurred last June. The elements of conventional deterrence form a basis for the armed forces modernization plan. The concept is a bit fluid and contains some elements of A2/AD, but despite modern acronyms the roots of the strategy can be traced to the classic book of B.H. Liddell Hart, Strategy:

The acquisitive state, inherently unsatisfied, needs to gain victory in order to gain its object – and must therefore court greater risk in the attempt. The conservative state can achieve its object by merely inducing the aggressor to drop his attempt at conquest – by convincing him that “the game is not worth the candle.”

2013 was not a bad year for the Polish Armed Forces, but this short list of ideas demonstrates how the concepts of national security and defense evolved and becomes ever broader.

Przemek Krajewski alias Viribus Unitis is a blogger In Poland. His area of interest is the context, purpose, and structure of navies – and promoting discussion on these subjects in his country.

Unmanned Naval Helicopters Take Off in 2013

The carrier take-off and arrested landings of the U.S. Navy’s X-47B demonstrator have garnered significant press attention this year. Less noticed however, is the rapid development of rotary-wing unmanned aerial vehicles in the world’s navies. Recent operational successes of Northrop Grumman’s MQ-8B Fire Scout aboard U.S. Navy frigates have led to many countries recognizing the value of vertical take-off and landing UAVs for maritime use.

International navies see the versatility and cost savings that unmanned rotary wing platforms can bring to maritime operations. Like their manned counter-parts, these UAVs conduct a variety of missions including intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR); cargo resupply/vertical replenishment; and in some future conflict will perform armed interdiction at sea. However, unlike the two- or three-hour endurance of manned helicopter missions, some of these UAVs can fly 12-hour sorties or longer. Other benefits include the ability for some models to land on smaller decks than manned aircraft, a much lower cost per flying hour, and importantly, limited risk to human aviators. Several international VTOL UAV projects have been recently unveiled or are under development, many of them based on proven light manned helicopter designs. Starting with a known helicopter design reduces cost and technical risks and allows navies to pilot the aircraft in no-fail situations involving human passengers such as medical evacuations.

Poland has two designs in the works, the optionally manned SW-4 SOLO and the smaller composite ILX-27, which will carry up to 300 kg in external armament. In July, the Spanish Navy announced a contract with Saab to deploy the Skeldar V-200 unmanned air system aboard its ships for counter-piracy operations in the Indian Ocean.

Russia’s Berkut Aero design bureau, in collaboration with the United Arab Emirate’s Adcom Systems have announced plans to develop an unmanned combat air vehicle (UCAV) based on Russia’s two-seat coaxial Berkut VL helicopter.

One of Schiebel’s rapidly proliferating S-100s mysteriously crashed in al-Shabaab-held Southern Somalia earlier this year, but in a successful turn-around, Camcopter S-100 conducted at-sea trials with a Russian Icebreaker in the Arctic later this summer.

Back on the American front, in July, Northrop Grumman delivered the Navy’s first improved MQ-8C, a platform largely driven by U.S. Special Operations Command’s requirements for a longer endurance ship-launched aircraft capable of carrying heavier payloads including armament. The Marine Corps’ operational experimentation in Afghanistan with two of Lockheed Martin/Kaman’s K-MAX unmanned cargo-resupply helicopters from 2011 until earlier this year was largely successful, but suspended in June when one of the aircraft crashed while delivering supplies to Camp Leatherneck in autonomous mode. Because of this setback, Lockheed has improved K-MAX’s autonomous capabilities, and added a high-definition video feed to provide the operator greater situational awareness. Kaman has also begun to market the aircraft to foreign buyers. Finally, a Navy Research Laboratory platform, the SA-400 Jackal, took its first flight this summer.

There are minimal barriers to VTOL UAVs wider introduction into the world’s naval fleets over the next few years. How much longer will it take for their numbers to exceed manned helicopters at sea?

This article was re-posted by permission from, and appeared in its original form at NavalDrones.com.