By Alex Calvo

Introduction. We begin the second installment in our four-part series with an examination of the relationship between nuclear weapons and a country’s hard and soft power, and then move to discuss “Hybrid warfare” under a nuclear umbrella. We next deal with the system’s opportunity cost and whether it may constitute an obstacle for conventional rearmament, and ponder its connection with the “special relationship” between London and Washington. In our final section, we examine Trident in light of the UK’s place within the European Union. Read Part One here.

The Bomb and a Country’s Image and Power, Hard and Soft

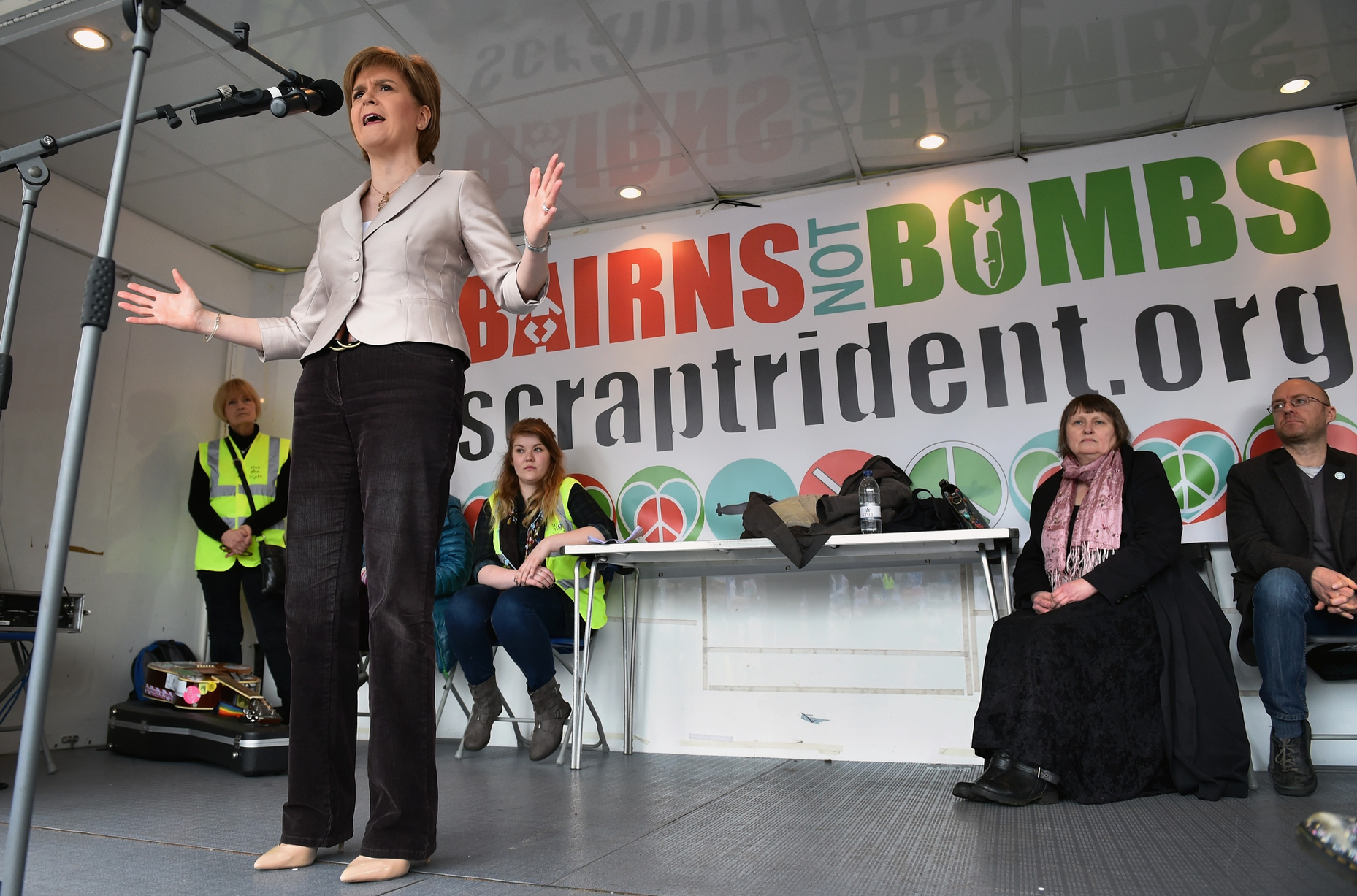

Concerning the second question posed earlier, whether a country needs to be a nuclear weapons state in order to be a top diplomatic power, right from the early days of the nuclear era possession of the bomb has been widely recognized as a major status symbol, marking a country as a big power and supporting its diplomatic stance. What matters most is to discuss whether we are just talking about national pride and image, or whether a country’s nuclear status is a significant contributor to its national power, that is the ability to constrain other countries’ options and shape their behavior in the pursuit of its own national interest. If the former is true, then it is to be expected that some people may come to see a nuclear deterrent as non-essential, given financial realities and more pressing needs, both within and without the realm of defense. Thus we may hear voices demanding that Trident be scrapped and its cost be allocated either to conventional defense or to non-defense spending or tax cuts. If, on the other hand, the latter is more accurate, then any discussion of the UK’s nuclear deterrent cannot be undertaken in isolation.

While no formal connection exists between UNSC membership and nuclear weapons, it is often considered to be no accident that all five permanent members are recognized nuclear powers. Despite the continued criticism of nuclear weapons, possessing them does indeed place a country in the top diplomatic league, and therefore if the UK renounced her own national deterrent, this may be seen as an anomaly, and evidence of decline into the minor league of diplomacy. At a time of renewed strife with the country facing possible aggression on at least three fronts (Russia, Gibraltar-Falklands, and Jihadism), the consequences may go beyond what may seem clear at first sight. It could be argued, on the other hand, that renouncing nuclear weapons may give a boost to the UK’s worldwide image, turning the country into a champion of disarmament and thereby bringing about a wave of goodwill resulting in additional soft power. Although it may sound logical, and may actually be in line with some of the motivations for the current policy of a minimal nuclear posture, history seems to indicate that such well meaning intentions would have the opposite result.

Furthermore, the UK’s policy of minimal deterrence has not been followed by other nuclear powers. Here we should stress that, although Western governments and observers have generally refrained from even mentioning it, Indian experts have had a field day stressing how the Ukraine accepted the removal of the nuclear weapons located on her territory and the country’s accession to the NPT as a non-nuclear weapons state, only to later see part of her territory grabbed and her very existence as an independent state questioned by those who chose to retain both nuclear assets and NPT weapons state status. This includes not only traditional nuclear hawks, but even observers who had always opposed nuclear weapons. For example, in April 2014 Swaminathan S Anklesaria Aiyar wrote “All my life I have opposed nuclear bombs. I have argued that such bombs are basically unusable; that, instead of ensuring security, they risk escalation of small conflicts into disasters; and that they lead to undesirable macho foreign policies. Most Indians exulted after India’s nuclear tests of 1998, claiming India was now a great power on par with the U.S. I cautioned that India was merely on par with Pakistan and North Korea. However, after seeing Ukraine bullied by Russia, I have to revise my views. Nukes are not useless, and may be essential deterrents” adding “Lesson for non-nuclear states: don’t depend for security on the big powers who will dump you when convenient. Disarmament is for wimps. Go get your own nukes if you can. More nuclearization will deter some invasions, but also increases chances of a nuclear clash or accident. It is not a panacea. But it is now inevitable.”

In the Ukraine herself some voices have regretted the 1994 Budapest Memorandums on Security Assurances “’We gave up nuclear weapons because of this agreement,’ Pavlo Rizanenko, a member of the Ukrainian parliament, told USA Today. ‘Now there’s a strong sentiment in Ukraine that we made a big mistake.’ Nuclear weapons may make the world nervous, but foreign troops rarely pay unannounced visits to nuclear states.”

“Hybrid Warfare” under a Nuclear Umbrella: Conventional and Non-Conventional Defense

With regard to the third issue, the relationship between nuclear and non-nuclear defense, this is sometimes discussed purely in terms of opportunity costs. To be precise, whether by retaining Trident the UK may be forced to implement defense spending cuts endangering conventional capabilities. It is of course true that any weapons system must be examined in terms of opportunity costs, and that we must be aware of what we may be losing or failing to acquire by preserving existing assets or purchasing new ones. This is even more the case following the 2010 announcement by the chancellor that the cost of the nuclear deterrent would be funded through the defense budget, as opposed to separately by the Treasury. George Osborne said “I have made it very clear that Trident renewal costs must be taken as part of the defence budget.”

Where we have to be careful is in drawing too strict a line between conventional and non-conventional weapons. This is sometimes done by observers who stress threats to the UK from non-state actors and non-nuclear weapons states, saying that the former cannot be deterred (because they do not control a territory and population which can be threatened with destruction if they attack the UK with nuclear weapons) and the latter cannot be dealt with using nuclear weapons because the UK deterrent is aimed at fellow nuclear weapons states. The first argument has merit and cannot be dismissed out of hand, yet is not sufficient in and by itself to defend an end to the nuclear deterrent on at least two counts: first, that while non-state threats are indeed important, state to state conflict remains a very real possibility, as clear from recent developments in Eastern Europe, the South Atlantic, and the Strait of Gibraltar. Second, that a non-state actor may be supported by a state, in which case the latter may be deterred, or may gradually evolve into a de facto state which, although not internationally recognized, may also have actual control over a population or territory and thus be equally liable to classical deterrence. Concerning the second argument, although it is true that British nuclear doctrine is mainly targeted at other nuclear weapons states, it is nowhere stated that it is thus restricted. As noted when examining a possible role for nuclear weapons in the defense of the Falklands, “while the British nuclear deterrent was not originally designed to deal with conventional aggression, and the UK doctrine mainly refers to dealing with nuclear threats or attacks, its documents do not rule out a first strike and more to the point do not provide any explicit assurance to non-nuclear weapons states.”

We then have the not often openly discussed issue of the relationship between nuclear forces and conventional and asymmetric combat. More precisely, whether nuclear weapons are necessary to wage conventional or asymmetric war, and in the British context, whether losing Trident would put a dent on the country’s other military capabilities. Here we have to be careful not to follow the simplistic logic that presents conventional and non-conventional capabilities as separate. Both from a practical historical perspective, and from a more theoretical and doctrinal one, they are clearly not. A country is often able to wage conventional or sub-conventional war precisely because it has the nuclear forces necessary to constrain the reaction by other actors. The Korean War is a classical example, the 1949 Soviet maiden nuclear test paving the way to a conventional war of aggression to unify the Peninsula. More recently, Russian sources stress not only the “hybrid” nature of armed conflict but the inclusion of the nuclear component in that “hybrid warfare.”

While many Western observers describe “hybrid warfare” or “hybrid war” as basically comprising a mixture of traditional armed force with special operations, information management and clandestine operations, the U.S. Army 2012 Unified Land Operations manual describing it as “The diverse and dynamic combination of regular forces, irregular forces, terrorists forces, and/or criminal elements unified to achieve mutually benefiting effects.” Russian observers emphasize that for it to be effective it must operate under a nuclear umbrella. The resulting deterrence enables Russia to engage in lower forms of conflict, while never losing sight of this connection. Thus, for an actor to be able to wage conventional and sub-conventional war, in particular where other nuclear powers may be directly or indirectly involved, it may be necessary to retain its nuclear deterrent. This means that the UK needs to preserve either Trident or a nuclear alternative to this system not only to directly deal with nuclear threats or the possibility of nuclear threats, but also to retain her freedom of maneuver when it comes to waging other kinds of war. Otherwise, the resulting loss would not only impact the nuclear domain, but the whole spectrum of military operations and diplomacy. Argentina’s recent dalliances with two nuclear-weapons states are a reminder that a national nuclear deterrent may be necessary to constrain the intervention of nuclear powers in a conventional or sub-conventional conflict with a non-nuclear weapons state.

Trident’s Opportunity Cost: A Bar to Conventional Rearmament?

An argument against Trident by some observers otherwise committed to national defense is that its high cost may have a disproportionate impact on conventional capabilities, thus indirectly damaging British national security and the country’s power and influence in the international stage. Official estimates put the cost of replacing the current submarines at between £15 and £20 billion, while some voices against extension argue that the real cost is higher, with Greenpeace for example putting it at more than £34 billion.

While Greenpeace’s figures may be suspect given its anti-Trident posture, work by such organizations may be useful in having a more realistic perspective of the likely costs involved, even more so in view of past cost overruns in the defense industry. Furthermore, it must be admitted that some of the official estimates do not include the whole spectrum of associated costs linked to the program. When Greenpeace’s report was published, a MOD (Ministry of Defence) spokesman said that “The 2006 white paper set out the costs [of Trident] at £15-20bn, not the £30-33bn that Greenpeace suggest. As stated in the 2006 white paper, the costs are at 2006 prices and VAT is not included. It is impossible to try and predict exchange rates and material costs over the course of replacing Trident.”

We have already made it clear that the opportunity cost of any weapons system is a major factor to be considered, and thus this argument cannot be easily dismissed. However, given the also explained link between nuclear and non-nuclear defense, should Trident come to be seen as too expensive, the best solution would be to replace it with another nuclear delivery system, rather than renouncing an independent national deterrent.

Last year was witness to an intense public debate on British defense spending, given the danger of falling below the NATO guideline of two percent. The debate went on into the run up to the general election, which saw the Conservatives gain an absolute majority and thus dispense with the need to share power with the Liberal Democrats. The new administration formally announced that London would keep spending two percent of British GDP on defense, although doubts remain as to whether some creative accounting may be employed to secure this goal. To some extent, the debate overlapped with that on Trident. However, as noted by some commentators, Trident is currently funded separately from the defense budget and “any savings which could be made by cancelling or changing the programme would not be realised until the next Parliament and beyond, up until the 2040s, which is when the vast majority of spending on the renewal programme will occur.” Both points should be taken into account when defending the view that Trident may be scrapped in order to fund conventional rearmament, since it is perfectly possible, from a political perspective, that no such impact would come to be realized. Furthermore, from a tactical perspective, voices soft on defense may conclude a tactical alliance with proponents of higher conventional defense spending with a view towards downgrading or terminating the national deterrent, only to turn against the latter once that objective had been secured. The end result would be a UK deprived of nuclear forces and with conventional capabilities even smaller than at present.

Trident and the “Special Relationship”

British nuclear policy has an influence on relations with Washington at different levels. First of all, the UK’s nuclear deterrent is a major contributor to the country’s power and thus its worth as an ally for Washington. Second, the existence of the deterrent may complicate calculations for any would-be aggressor in the Euro-Atlantic Area, and while this is a complex issue defying simplistic analysis, it may result in a greater combined deterrence capability since that aggressor would need to ponder not just the American but also the British (and French) reaction. However, while recent U.S. defense policy seems to be putting more reliance on key regional allies, this basically refers to the conventional arena, with voices in favor of letting additional allies develop an independent deterrent being in the minority. Among the exceptions we can cite a National Interest article arguing that “America’s policy of opposing the proliferation of nuclear weapons needs to be more nuanced. What works for the United States in the Middle East may not in Asia. We do not want Iran or Saudi Arabia to get the bomb, but why not Australia, Japan, and South Korea? We are opposed to nuclear weapons because they are the great military equalizer, because some countries may let them slip into the hands of terrorists, and because we have significant advantage in precision conventional weapons. But our opposition to nuclear weapons in Asia means we are committed to a costly and risky conventional arms race with China over our ability to protect allies and partners lying nearer to China than to us and spread over a vast maritime theater.”

Trident relies to a considerable extent on U.S. technology, the UK nuclear weapons program being heavily dependent on America ever since Washington resumed nuclear cooperation in 1958. As noted by think-tank BASIC, “The United Kingdom’s Trident missiles are purchased directly from the United States under the terms of the 1963 UK-U.S. Polaris Sales Agreement, amended in 1980 and 1982 to govern cooperation over the Trident I (C4) and Trident II (D5) generations of submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), respectively. Cooperation between the two states’ nuclear weapons complexes operate under the 1958 Mutual Defense Agreement, renewed every decade and up again for renewal next year (2014). The UK does not actually own any individual missiles, but purchased the rights to 58 missiles from a common pool held at the US Strategic Weapons facility at the Kings Bay Submarine Base, Georgia.” Thus, the U.S. defense industry has a clear stake in the program’s continuity, and this may bring a degree of pressure from Washington, irrespective of the two previous factors discussed earlier.

In more than one way, Trident reflects the complex nature of the British nuclear deterrent and of nuclear cross-Atlantic relations. As already mentioned, after spearheading Allied work in this area, the UK left matters in American hands, only to find access restricted after the war and having to engage in a major effort to ensure a place at the nuclear table. Being under national command, yet reliant on American technology, Trident reflects some of the ambiguities and contradictions in the UK’s post-war status and foreign policy: a major power yet one closely associated and dependent on one of its allied superpowers. Like its predecessor, Polaris, Trident is based on “American missiles, British submarines and warheads.” The missiles are the same employed by the U.S. Navy. One of the traditional arguments against Trident is that it is not fully “independent,” with, for example, the missiles being serviced in the United States.

Keeping Tident in place, if accompanied by a retention of non-nuclear capabilities, may facilitate preserving British influence in Washington. Scrapping it, in particular if accompanied by a further deterioration in conventional capabilities, is likely to have the opposite effect. Replacing it with a system less reliant on US technology, or even purely British, would likely prompt both industrial and financial concerns on the other side of the Atlantic, and political ones as well. It is beyond the scope of our series to examine them in depth, but they should be noted.

In addition, we should also remember that working with the United States also poses some technical challenges given the different development and procurement plans on the two sides of the Atlantic. For example, as noted by the Guardian, “The U.S. has decided to extend the life of its existing D5 missiles to 2042, a decade before the new British submarines would retire. The UK would therefore have to put new U.S. missiles in then-old submarines.” On the other hand, in addition to the political considerations already mentioned, working with U.S. technology means the UK does not have to face the full cost of developing and servicing a whole delivery system on her own.

Trident, the UK, and the European Union

The debate over Trident is also linked to another perennial discussion in British politics, namely that concerning the country’s relation with and place in Europe. This debate is becoming more and more intense as we approach the 23 June referendum, and one of its aspects is security and defense. Some years ago a certain consensus emerged, centered on the notion of a EU restricted to little more than a free-trade area, but this has now been effectively dismissed in the minds of many, thus simplifying the terms of the debate while at the same time making it even more intense. For a significant number of Britons, the UK faces a choice between recovering her full independence or becoming a European province ruled by Brussels, with national defense gradually giving way to supranational arrangements.

The relationship between European policy and nuclear policy is complex and defies simplistic linkages. However, those favoring the gradual dilution of British sovereignty into a European federal state logically tend to lean against the renewal of Trident, since the whole concept of an independent nuclear deterrent is based on the assumption that there is indeed a national sovereignty to protect and project. It is no coincidence to see some of the most ardently pro-EU voices in British political life engaged in an equally intense, parallel, campaign against Trident. For those, on the other hand, favoring British sovereignty and the preservation of traditional British liberties under a constitutional monarch, nuclear weapons policy remains an important aspect of the defense policy debate, although this does not mean that they necessarily support Trident or a nuclear alternative.

Some European observers have noted how Trident’s continuity is not only good for British national security but for that of other European nations. A German security and defense blogger has argued that “For legal, political and financial reasons, there will never be any kind of multinational European sea-based nuclear force. However, European countries still need a nuclear umbrella for their security. If you do not believe that, please consult our Baltic and Polish friends,” adding that despite U.S. commitment to nuclear modernization “it is yet unclear, if the US Navy’s future sea-based deterrent will be large enough to span up a worldwide nuclear deterrent as we have it today” meaning that “Europe and the UK cannot afford to rely on that America provides nuclear free-rides forever.” While conceding that London may not retaliate against aggressors employing nuclear weapons on another European country, the text emphasizes how the possibility that she might make their “life much harder, if they at least have to take the risk of retaliation into account.”

It should also be noted how, although the European Union’s narrative is to a great extent reliant on the notion that it has brought peace to the old continent, making war unthinkable, this pretense does not stand to any serious scrutiny. British citizens remain under threat at the hands of a fellow EU member state which does not recognize their right to self-determination, while enjoying the continued support of British taxpayers. This is only one of many contradictions that cast a doubt on the proposition that the UK may renounce her own defense policy, to be taken over by the EU. In connection to this, it should also be remembered that the UK retains the responsibility to defend different British Overseas Territories, including the Falklands and South Georgia, also under threat. Since not only do these territories not belong to the EU, but in the 1982 Falklands War it was clear that the degree of support to be expected from fellow member states was rather limited, any move toward deeper European integration may well be incompatible with their continued security.

Alex Calvo, a guest professor at Nagoya University, Japan, focuses on security and defense policy, international law, and military history in the Indian-Pacific Ocean Region. He tweets at Alex__Calvo and his papers can be found here. Previous work on British nuclear policy includes A. Calvo and O. Olsen, “Defending the Falklands: A role for nuclear weapons?” Strife Blog, 29 July 2014, available here.

Featured Image: HMS Vengeance returning to HMNB Clyde, after completing Operational Sea Training. The trials were conducted in Scottish exercise areas. (Tam McDonald/MOD)