A human disaster is currently happening in the Mediterranean Sea where more than 10,000 migrants have been picked up as they attempted to enter Europe from Libya. The International Organization for Migration estimates that nearly 1,830 migrants have died on the sea route this year compared to 207 in the same period last year.

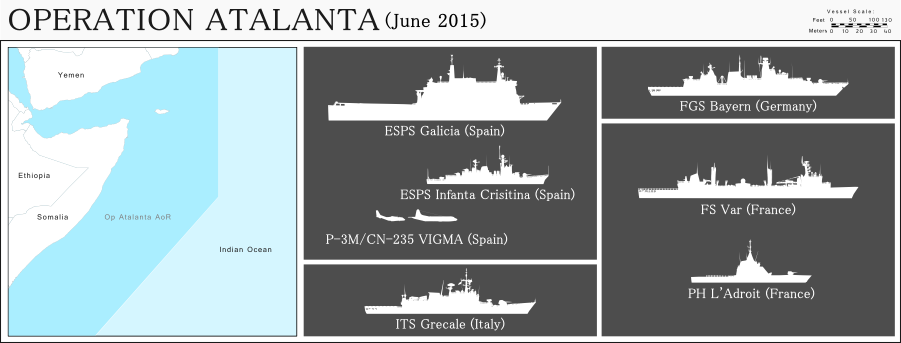

Traffickers started taking advantage of the breakdown of authority in Libya to pack boats with paying migrants willing to cross the sea for a better life. Meanwhile, the European operation against piracy in the Indian Ocean (EUNAVFOR Atalanta) has become a reference for possible maritime operation in the Mediterranean against those traffickers.

EUNAVFOR: an operation meant to fight piracy

Created in 2008 as an operation to protect merchant ships against pirate attacks, mainly in the Gulf of Aden and particularly in the IRTC (International Recommended Transit Corridor) put in place to make sure vessels from the World Food Programme would reach the populations in need, Atalanta has become much more than a simple EU joint operation.

If the destruction of ships was not part of the original objectives of Atalanta, its actions soon grew offensive: in spring 2010, 18 months after its start, Atalanta adopted enhanced intelligence and surveillance methods allowing it to disrupt both “pirate bases” and pirate ships.

The tactics used by the EU operation (and by other forces) to enter a maximum of mother ships (not simple skiffs) was one of the operation’s success vectors. But those vessels were empty most of the time and no collateral risk was therefore expected.

Recognition means and intelligence

Operation Atalanta has strong recognition means with several maritime patrol aircraft based in different parts of the Indian Ocean (mainly in Djibouti and Seychelles) to regularly cover the area. From time to time, an AWACS aircraft is also required to lead strategic surveillance of the zone. And at the tactical level, some vessels (mainly Dutch) used maritime drones.

The interrogation of arrested pirates is a very important source of information and merchant ships that cross the zone play an important role in passing information to the Maritime Security Centre – Horn of Africa, the maritime information centre set up at Northwood military headquarters in the UK and the various information collected in neighbouring countries (Kenya or Djibouti).

The Maritime Security Centre – Horn of Africa (MSCHOA) is an initiative established by EU NAVFOR with close co-operation from industry. It provides 24-hour manned monitoring of vessels transiting through the Gulf of Aden, whilst the provision of an interactive website enables the Centre to communicate the latest anti-piracy guidance to industry, and for shipping companies and operators to register their vessels’ movements through the region.

Owners and operators who have vessels transiting the region are strongly encouraged to register their movements with MSCHOA to improve their security and reduce the risk of attacks or capture. Additionally, the “Best Management Practices for Protection against Somalia Based Piracy” (BMP) and further information about combating piracy, and what action to take should they come under attack, can be downloaded on the MSCHOA’s website.

A further initiative was the introduction of Group Transits; vessels are co-ordinated to transit together through the IRTC. This enables military forces to “sanitise” the area ahead of the merchant ships. MSCHOA also identifies particularly vulnerable shipping and co-ordinate appropriate protection arrangements, either from within Atalanta, or other forces in the region.

In 2012, the need for ground actions was put forward.

Operations on land

In 2008, the crew of the Ponant, a French ship has been reported as having been taken in hostage by one of the four most powerful local groups, the Somali marines, who usually launched their operations from Garaad.

After the release of the Ponant, Admiral Gillier launched a helicopter raid by boarding commandos to intercept pirates on land. This air raid took place with the agreement of the Somali government. This is the only time where pirates were followed on land after the ransom was paid. The question was asked if the extension of Atalanta’s mandate would allow armed forces to track pirates on land. In April 2012, authorizations to destroy the logistics depots, i.e. “pirates bases” was obtained. These actions were also a way of saying to pirates “we can reach you anywhere.” This possibility of ground action, however, has been used only once, in May 2012, in an action by the Spanish navy. It was apparently enough to convince some local leaders that it was too dangerous for them to help pirates.

Recent actions in Yemen

In the margin of Atalanta, the French patrol boat L’Adroit was deployed on March 30, for two weeks off the Yemeni coast, where he led the evacuation of 23 French nationals from Aden, in difficult conditions. L’Adroit also escorted several Yemeni dhow between the ports of Djibouti and Al Mukah, contributing to the evacuation of nearly a thousand people from Yemen, including more than 500 Djiboutian refugees. The French ship then made call in Djibouti to refuel. Several authorities went on board, including the Ambassador of France to Djibouti, to congratulate the crew for its actions. L’Adroit now resumes his patrol off the Somali coast as part of the EU mission Atalanta to fight against piracy.

EUNAVFOR MED: Switching from pirates to migrants?

This triple action: information, sea destruction and destruction on land was recently considered as a model for a possible CSDP operation against human traffickers in the Mediterranean. On 23rd April, an extraordinary European Council gathered to speak on the sensitive subject of migrants in the Mediterranean.According to a draft declaration, EU leaders turn towards Atalanta to reduce –if not end- the shipwrecks of migrants. We must “undertake systematic efforts to identify, capture and destroy the ships before they are used by traffickers”, the document reported.

The head of European diplomacy,Federica Mogherini, “was invited to immediately begin preparations for a possible security and defence operation, in accordance with international law.” The head of the Italian Government, Matteo Renzi, even requested the examination of the possibility of conducting “targeted interventions” against smugglers in Libya, which over the years became the country of embarkation of migrants and asylum applicants towards Italy and Malta.

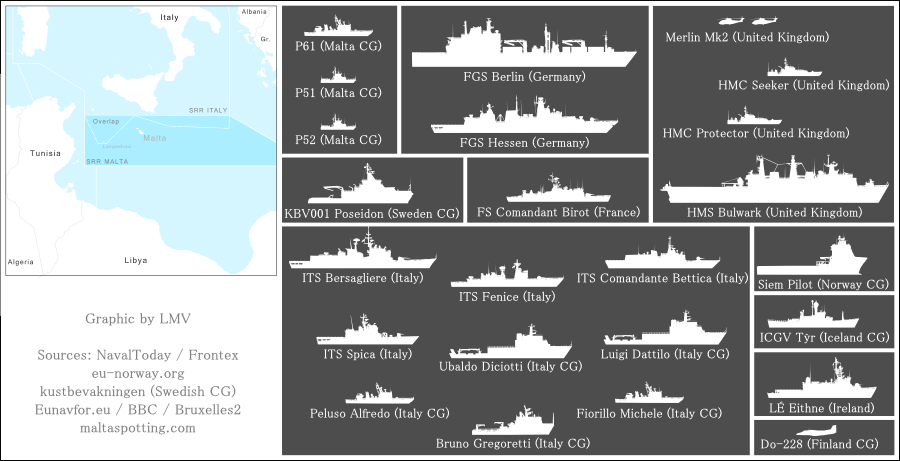

If accepted, the organization of the EU military operation would be a first in the fight against illegal immigration but, of course, its implementation would take time. But in order to do destroy boats in Libya, a legal mandate is required from the UN. The ground action possibility for the Atalanta naval force in Somalia was almost never used because of its difficulty. EU leaders also need to think about measures to intervene during the crossing of migrant boats. And this would probably require giving more money to Frontex, the EU’s border control agency. However, the destruction of ships used by migrants already takes place at sea.

There are three main reasons for this:

First, abandoned vessels are a hazard to navigation, especially at night, when, because of their size and lack of lighting, they cannot be seen, even in good weather. Second, a ship lost at sea can be seen from an airplane and it is not always clear if anyone is onboard. To maintain the high quality of emergency rescue at sea, it is necessary to destroy those boats immediately after all migrants have been evacuated.Third, abandoning a vessel could lead to the risk of it being used once again by a new team of traffickers.

For example, German Chancellor Angela Merkel has officially confirmed on the 19th May during a joint press conference with President Hollande, that, since the beginning of sea rescue operations where the German navy was involved, “five inflatable boats and a wooden boat were sunk”.

The High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Federica Mogherini, declared: “the fundamental point is not so much the destruction of the vessels but it is the destruction of the business model of the traffickers. If you look at business model of the traffickers and the flows of money involved in trafficking, it may be that that money is financing terrorist activities.” Stressing the same point, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg said: “one of the problems is that there might be foreign fighters, there might be terrorists, also trying to hide, to blend in on the smugglings vessels trying to cross over into Europe.”

Know your enemy!

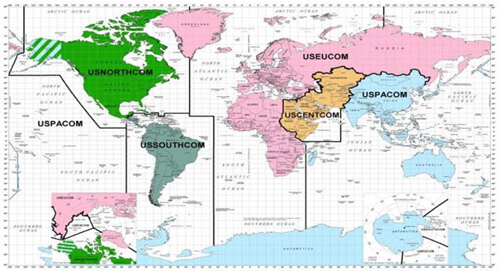

On 18th May, Ministers of Foreign Affairs and Defence of the 27 Member States of the EU (Denmark opted out of the common defence agreement after the Danish ‘no’ vote at the Maastricht referendum in June 1992) gave their “green light” to EUNAVFOR Med. Since the United Nations did not take any resolution yet, the operation should start with a first phase: the exchange of information and intelligence. This is fundamental, since, without an accurate tracking of information concerning different traffickers, different means employed, etc., it would be almost impossible to fight this traffic. This means air observation (maritime surveillance aircraft, UAVs, helicopters …) and imaging (radars, satellites, etc.).

Furthermore, if the goal is to neutralize these networks and to bring the perpetrators to justice, it is necessary, indeed, to have specific evidence against them. Laws also need to be updated to arrest traffickers on the high seas.

It will not be too difficult to organize action in the Libyan waters since most of the interested navies such as Greece, Italy, France, Spain etc. are already almost positioned in the international waters near Libya. The Mediterranean is really a “mare nostrum”. All European marine meet there to participate in combined manoeuvres (within NATO in general) or to visit the Indian Ocean – to participate in the anti-piracy operation in the operation of allies in Iraq, etc. – So, the cost for the navies to act through EUNAVFOR Med is reduced.

The General Operations Quarter installed in Rome, is already operational as it is currently used for Triton operation conducted under the aegis of Frontex (the European border control agency). Its military commander is Credendino Enrico, an Italian admiral. After this first phase centred on intelligence gathering and surveillance of smuggling routes leading from Libya to southern Italy and Malta, EU ships would start chasing and boarding the smugglers’ boats in a second phase. Summer is the high season for trafficking; this is why it is necessary to act quickly.

A dramatic situation but where is solidarity?

Despite the show of unity on the military action, the EU appears increasingly divided on the question of mandatory numbers of asylum seekers which should be accepted by member states, according to population size, wealth, and the number of migrants already hostel, as proposed by the European Commission on 13th May.

Ten countries have already spoke out against it, namely Spain, France, Britain and Hungary. Spanish Foreign Minister Jose Manuel Garcia-Margallo said the proposed quota for Spain doesn’t take into account the nation’s sky-high jobless rate of 24 percent and its efforts to prevent illegal migration from African nations. Police in the Sicilian port of Ragusa, meanwhile, arrested five Africans suspected of navigating a rubber life raft packed with migrants that was intercepted at sea last week. Hungary’s PM Viktor Orban has said the plan is “madness” and France’s Manuel Valls called it “a moral and ethical mistake”.

Why are all politicians so afraid to hold a hand to migrants? In 1979, French politicians and intellectuals put their disagreements aside and welcomed more than 128,531 Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees, fleeing communism and ethnic persecution, not knowing where to go.” Jean-Paul Sartre and Raymond Aron, two intellectuals, who were politically opposed, gathered around a common cause. A few months earlier, this heterogeneous coalition was established to charter a boat, with MSF, to travel around the South China Sea and bring relief and assistance to boat people in distress.

France hosted and helped migrants to settle and be integrated on its soil. Much of the Asian community in France, especially in the thirteenth arrondissement of Paris, is the result of this wave of immigration of boat people fleeing the former French colonies in Indochina.

Today, thousands of men and women are fleeing war in Syria – a former territory managed by France-,or the dictatorship in Eritrea, or the poverty of sub-Saharan Africa and no one is there to hand them a hand. David Cameron recently announced that he would send a ship of the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean but any migrant rescued by the British Navy would be deposited on the coasts of the closest countries, probably Italy.

We can find thousand of reasons not to help these people but I have one question: when did we stop being human?

After studying law and international relations, Alix started working on the first cycle of conferences “Defence and Environment: a new way of thinking” about the impact of defense activities on the environment. Alix served as a Navy officer and a political adviser to the New Zealand Consul in New Caledonia. Since 2013, Alix is also the Asia-Pacific market analyst for the French and English publications of Marine Renewable Energy as a renewable energy consultant. She currently lives in New Caledonia. She is writing a PhD on the law of marine energy resources.

Louis Martin-Vézian is the co-president of the French chapter of CIMSEC, and produces maps and infographics features on CIMSEC and other websites. His graphics and research were used by GE Aviation and Stratfor among others.

ADM John Harvey, USN (ret), joins us to discuss the Third Offset and the “Human Offset.” Third Offset is Defense Undersecretary Robert Work’s strategy to embraces the US technological advantage, pushing the throttle to the max through a suite of development efforts. However, ADM Harvey worries that this technological emphasis will pull attention from other foundational areas – like talent management and development – as well as what he sees as a dedication of our resources into dominance less-achievable in our globalized civilian-led tech economy.

ADM John Harvey, USN (ret), joins us to discuss the Third Offset and the “Human Offset.” Third Offset is Defense Undersecretary Robert Work’s strategy to embraces the US technological advantage, pushing the throttle to the max through a suite of development efforts. However, ADM Harvey worries that this technological emphasis will pull attention from other foundational areas – like talent management and development – as well as what he sees as a dedication of our resources into dominance less-achievable in our globalized civilian-led tech economy.