This month the United States will begin its two-year Chairmanship of the Arctic Council, a high-level intergovernmental forum that primarily addresses environmental protection and sustainable development issues in the Arctic region. The Arctic Council, which also includes Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, and Sweden (also referred to as the A8), was formed as a result of the Ottawa Declaration in 1996. As interest in the Arctic has grown over the years, so too has the status of the Arctic Council.

With the Arctic becoming more attractive, there will be opportunities for major international players to share information and best practices for sustainable development and safe navigation through the busy shipping lanes in the region. It is realistic to believe that all Arctic and major trading nations benefit from open access to shipping lanes in the Arctic. However, the geopolitical significance placed on the Arctic by some actors may hinder information-sharing of all types between states active in the region. For example, Arctic states, who all have different coast guard structures, could deny information to others in order to protect sovereign rights. Furthermore, non-Arctic states, particularly China, may build influence in the region to pursue its own interests. China’s economy relies heavily on shipping and plans to use the Arctic to ship around 15% of its international trade by 2020. A precedent must be set that manages possible competing influences in the Arctic to secure peaceful usage of the region.

Besides the permanent members of the Arctic Council, there are non-Arctic states with Observer Status who, at the moment, do not play a significant role in the Council’s decision-making, but may in the future. Many states have an interest in the Arctic, which is likely to drive certain actors to pursue unilateral actions to enhance their Arctic objectives if there is no change to the status quo. With top energy consumers and economic powers like China and India as Observers, along with Russia’s aggressive activity in the Arctic, as evidenced by its large-scale military exercises, the U.S. must exercise a leadership role to coordinate collaboration between all states interested in the Arctic, mitigating tensions and ensuring freedom of the seas.

Most Americans are probably not aware of what the Arctic Council is and that the U.S. will be its Chair starting later this month. This U.S. Chairmanship is sure to differ from its predecessor Canada’s, as the U.S. seems adamant about having a strong focus on climate change while also building upon Canada’s theme of economic development in the Arctic. Because issues in the Arctic affect a number of nations, the United States has a grand opportunity to use its Arctic strategy to help guide multilateral cooperation to promote regional governance and stability.

Due to the geopolitical factors associated with the Arctic, it is important to remind the American public of the potential opportunities for the U.S. to further its goals in the High North. With competing interests in the Arctic, the U.S. should seek out opportunities to strengthen its cooperation with the other Arctic nations. Russia has been the most active in the Arctic by margin. Relations between Russia and the other A8 have been strained since Russia annexed Crimea, but the U.S. should prevent a “Crimea flu” from taking place, while also not allowing Russia to encroach upon its Arctic neighbors’ sovereign territory. Whether it be technological partnerships to advance oil and natural gas exploration or multilateral efforts within the Arctic Council to develop a comprehensive framework aimed at Arctic security, the U.S. should make it a goal to work with Arctic and non-Arctic states to further unity and stability in the region.

U.S. Approach to the Arctic Region

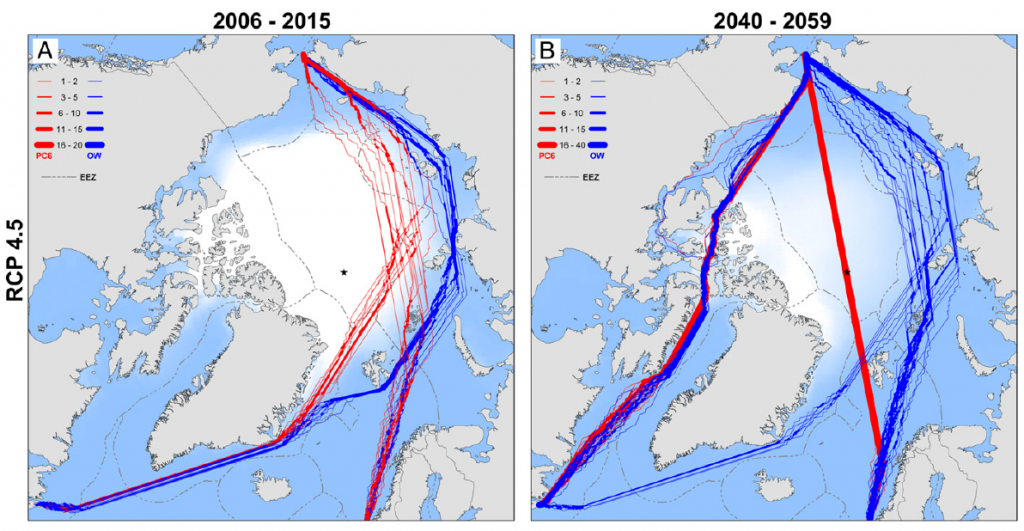

As demonstrated by the Obama administration’s Implementation Plan for The National Strategy for the Arctic Region, the United States will look to address certain themes during its Chairmanship of the Arctic Council. Those themes include: Arctic Ocean safety, security and stewardship; improving economic and living conditions; and addressing the impacts of climate change. These issues will become increasingly more important as the diminishing polar ice cap will make the Arctic broadly accessible and vastly enhance the region’s appeal. Experts at the Department of Commerce’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predict that based on current trends the Arctic will be ice-free in the summertime before 2050. The melting of Arctic ice will result in new complex issues concerning the exploitation of natural resources, freedom of navigation, and territorial sovereignty.

Preventing tensions in these focus areas is in the interest of the Council, as all seek stability in the Arctic. The challenge though is for all Arctic nations to understand that inter-council tensions will threaten their interests. As stated in a report by the Director of National Intelligence last year, “Some states see the Arctic as a strategic security issue that has the potential to give other countries an advantage in positioning in their military forces.” Militarizing the Arctic may seem advantageous to individual states in the region, but doing so weakens Arctic governance and threatens the interests of global commerce. Thus, it is important to persuade all Arctic states, particularly Russia, that military activity in the High North is likely to deteriorate the Arctic’s future economic viability.

In addition to the themes laid out in America’s Implementation Plan for the Arctic, there are certain goals the U.S. is looking to achieve over the next two years. As stated by Julie Gourley, a Senior Arctic Official at the State Department, during a conference in Washington, DC this past summer, U.S. overarching goals while Chair of the Council are to introduce new projects and initiatives into the Council; raise public awareness of the Arctic and why it is important to U.S. interests; and strengthen the Council as an intergovernmental body. The U.S. will focus on cooperation among the A8 on implementing renewable energy projects in the region, especially solar, wave, and wind, while also developing information and communication technologies to foster partnerships. Increasing public awareness of the Arctic could garner more support for U.S. activity in the Arctic and help expand economic development. The U.S. Government is planning to allow Shell to restart its drilling for oil in the Arctic, while also continuing to work on its Draft Proposed Program that would allow three lease sales in Alaska (Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea, and Cook Inlet areas). The administration’s program, according to Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell, would make available nearly 80 % of Alaska’s undiscovered technically recoverable resources.

Based upon the Obama administration’s literature, it seems that the U.S. is placing more emphasis on environmental stewardship than economic development when it comes to its Arctic strategy. Preserving Arctic ecosystems and limiting the negative impact of energy exploration on the environment are factors that must be considered; however, not finding the right balance may cause the U.S. to fall further behind in acting as a strong voice in international Arctic policy.

Natural Resources in the Arctic

According to a U.S. Geological Survey 2008 report, the Arctic comprises 22% of the world’s remaining undiscovered, technically recoverable petroleum resources. These resources include 13% of undiscovered oil, 30% of undiscovered natural gas, and 20% of undiscovered natural gas liquids to the Arctic. It is projected that the Alaskan Arctic region holds the largest undiscovered Arctic oil deposits, approximately 30 billion barrels.

Not only can the U.S. benefit from Arctic oil and natural gas, there are also mineral resources that may be an even more important economic driver. Examples of such resources include zinc, lead, gold, coal, iron ore, nickel, and palladium. As noted in a recent report by the Congressional Research Service, without the appropriate infrastructure and funding, these natural resources cannot be appropriately explored and extracted.

In order for the U.S. and the other A8 states to take advantage of the economic value of the High North, it will require an Arctic that is stable for passage by vessels and safe exploration of resources. As the next Chair of the Arctic Council, the U.S. should develop a cooperative effort among the A8 to focus on Arctic security to assure stability and maritime safety in the region.

Preserving Stability in the Arctic

Given the number of territorial disputes and the vast amounts of natural resources in the region, there is the possibility that tensions could rise among the Arctic states. Commerce through the Arctic will only increase while the Arctic melts, thus, it is imperative to prevent conflict that may disrupt maritime trade and security. To preserve peace and security in the region, the U.S. can act as a guardian in strengthening regional cooperation through confidence and security building measures with the other Arctic nations.

Presently, military conflict in the Arctic does not look realistic. However, Russia, who has been the most active in the High North, has placed a strong emphasis on the Arctic in its military doctrine. Russian Defense Minister Army General Sergei Shoigu said in February, “A broad spectrum of potential challenges and threats to our national security is now being formed in the Arctic. Therefore, one of the defense ministry’s priorities is to develop military infrastructure in this zone.” Russian military buildup could be destabilizing, which is why the U.S. should implement intergovernmental mechanisms to reduce future tensions.

The U.S. could introduce confidence and security building measures that would allow the A8 to cooperate on maintaining stability in the Arctic. For instance, the U.S. could lead an effort to establish an annual forum that brings the heads of state of the A8 countries to discuss Arctic security issues. Government officials from the Arctic Council members have met on several occasions to discuss security issues in the Arctic, such as: the Arctic Security Forces Roundtable, Coast Guard Forum, and Northern Chiefs of Defense Meeting. However, having the U.S. President call upon the other A8 leaders to meet would demonstrate America’s commitment to upholding security in the Arctic.

Other mechanisms to preserve peace in the Arctic could include bi or multilateral cooperation on Arctic technology or infrastructure for energy exploration in the region, and possibly an annual Arctic security exercise between the A8 to strengthen maritime safety procedures. For the former to occur, the U.S. administration will need to show more willingness to pursue such projects. To start, it would be beneficial for the United States to invest in the production of new icebreakers to support security exercises. A Foreign Affairs article lays out several reasons as to how new icebreakers can enhance U.S. security in the Arctic and foster international cooperation. Additionally, progress in renewable energy in the Arctic is beneficial to all and could be a leading example in the potential of this technology. With all Arctic states seeing the importance of unconventional energy sources, collaboration in this sector through government-initiated development programs could assist in strengthening Arctic security.

There are multiple opportunities for the U.S. to take a leading role in strengthening Arctic security for decades to come. The U.S. can lead efforts to efficiently manage governance in this new common space by having the A8 establish a Working Group or framework that outlines shared responsibilities of security in the Arctic, to collaborate with the A8 to develop infrastructure needed to support transportation through the Arctic (such as a networked maritime domain awareness fusion centers encircling Arctic or other communication systems), and to create capabilities required to oversee and police the Arctic waters. All of these efforts can accommodate the needs of all Arctic nations; however, the U.S., as well as the other A8 members, will need to significantly fund such efforts, which seems difficult with today’s budget constraints.

A Historic Opportunity Awaits the U.S.

Chairing the Arctic Council provides the U.S. with the chance to more effectively implement collaboration among the Arctic nations. Of course, not everything the U.S. wants will be achieved, as the Council requires consensus by all eight states to move forward with any activity. Instead, the U.S. should look for opportunities to advance the interests of all Arctic states for policy to turn into action during the U.S. Chairmanship.

Accomplishing all of its geopolitical goals in the Arctic will be difficult. The United States has trouble funding its own projects in the Arctic, whether it be the exploration of natural resources or building an icebreaking fleet. Even the Council as a whole has issues with funding, which has impeded certain initiatives. The next two years will be of high importance for the U.S. in terms of establishing itself as a key Arctic state. Therefore, all levels of the U.S. Government should work together with their Arctic partners to take advantage of this historic opportunity.