India’s Role in the Asia-Pacific Topic Week

By Major Ahmed Mujuthaba

The Maldives: an Asiatic trinket trickling down from the tip of southern India in the middle of the blue economy’s hub. Even though it is popular for its crystalline waters and sun bathed beaches, recently Maldives has been appearing on the minds and finds of security strategists. So why have strategists shifted their gaze to this tiny tourist destination all of a sudden? Two reasons: India and China.

To learn more about the verities behind Chinese and Indian interests in Maldives, it is imperative to spare some ink on its geopolitics. Maldives is a marine resource-bound nation with its authoritative territories, when combined, consist of 98% sea. The 2% of land is comprised of approximately 1190 islands with a size of no more than 14 kilometers (8.7 miles) and elevating less than 1.5 meters (5 foot) above sea level. These islands are spread on the Indian Ocean from north to south for 863 kilometers (from latitudes 07° 06’ N to 00° 42’ S centered on longitude 73°E), conjoined into rings of islands known as atolls.

Due to its vastly resourceful and untouched marine environment, the Maldives obtain most of its foreign revenue from selling its serene and scenic beauty through tourism. Maldives’ tourism is one of the most high-end tourist industries in the world. This industry takes a bountiful slice of 42% from the nation’s GDP and accounts for 60% of its foreign income receipts.

To cater to this growing tourist industry the Maldives has gone into private and/or foreign partnerships to develop holiday resorts on uninhabited islands. The unique system of one-resort one-island has been successfully fending for the population since its introduction in 1972. As the country imports most of the required essentials, successful sustenance of the tourism industry is crucial for the population.

Notwithstanding this booming tourist industry, the Maldives remains a vulnerable nation in voluminous ways. Some of these vulnerabilities can be fanned down to a number of areas.

First and foremost is its economic dependence on tourism, which fluctuates wildly when the world economy slumps even an inch. Second is the country’s dependence on foreign imports, which stresses whenever diplomacy or economy strains. Third is the limited and strained basic services and facilities such as health, power and water, where the latter two have a cascading effect based on global oil prices.

Fourth is the lack of skilled human resources to meet the demands of growing industries in the country, which is compensated by an expatriate population accounting for over a fourth of the locals. Fifth is the constraint on security forces to prevent or counter any conventional aggression towards the country’s sovereignty.

Foreign aid and assistance is an important requisite for alleviating these vulnerabilities. Hence, a robust and charismatic foreign policy remains an essential tool for the development of Maldives.

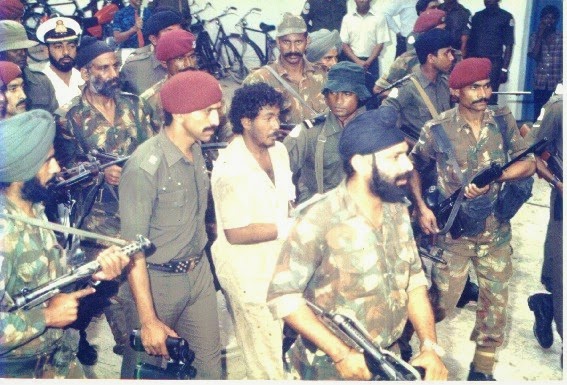

India, being the largest and closest resourceful neighbor to the Maldives, has enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship with the small island state for years. The highlight of Indian assistance was witnessed during the 1988 November 3rd incident, when mercenaries led by a Maldivian businessman attempted to take-over the government of President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom in an armed coup. On the request of the president of Maldives, the government of India rushed its army paratroopers and naval units to subdue the mercenaries.

Other notable influxes of Indian assistance include the opening of the nation’s largest hospital in 1995, the gifting of a ‘Trinket’ class fast attack craft (FAC) in 2006, the gifting of a ‘Dhruv’ helicopter in 2010, the opening of the country’s first military hospital in 2012, and opening of the Maldives National University’s Faculty of Hospitality and Tourism Studies (FHTS) building in 2014.

India’s footprint remains conspicuous in the Maldives in economic, diplomatic, and military aspects. Though this may be so, winds have not been always fair and seas neither calm between India and Maldives. In 2012, the government of Maldives prematurely scrapped an Indian investment made in the Maldives, which was also the largest foreign investment ever made in the island nation, amounting to USD $511 million.

This move demonstrated to New Delhi that Maldives was capable of making unilateral stances in a sovereign manner, whether it may or may not harm Indian interests. In the following year, the new government led by the current president, Mr. Yameen A. Gayoom initiated mechanisms to pacify the strained relations between the two nations.

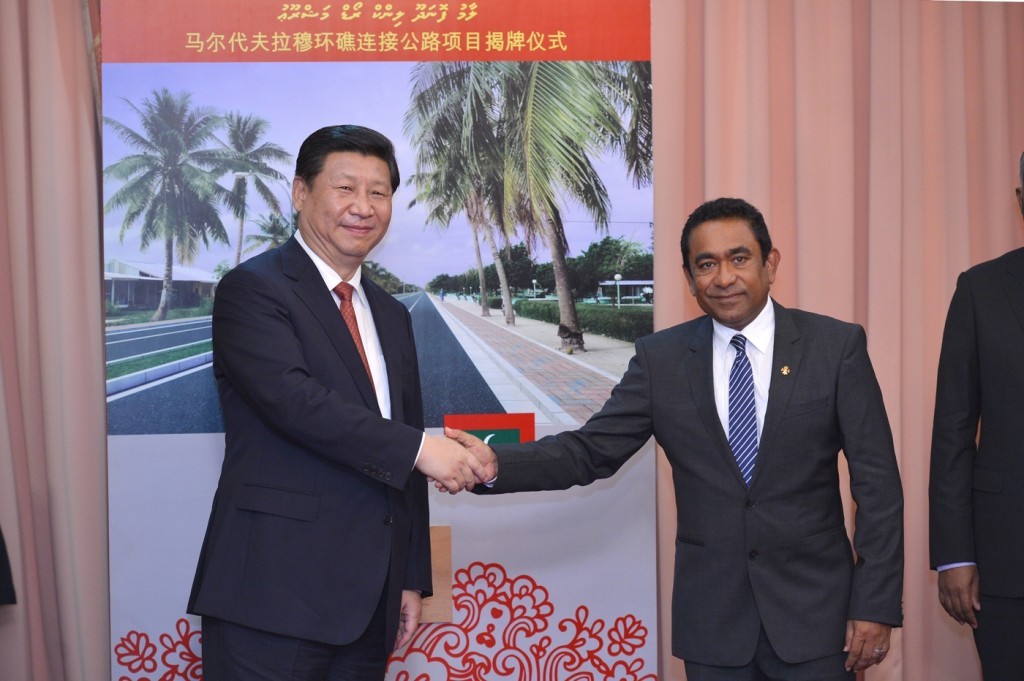

Upon taking office, President Yameen made his first state visit to India in 2014, signifying the importance of maintaining close ties with India. But it was the subsequent visits he made to China that took away the gaze of the foreign media. President Yameen made three official visits to China in 2014. In a reciprocal move, the Chinese president Xi Jinping made history in September 2014 by being the first Chinese president to visit Maldives. These interactions are encouraging to strategists desirous in their quest to find China’s next possible ‘pearl.’

It is a well-known fact that China has been modernizing and expanding its navy (PLAN) at a rapid pace, aiming to shift its traditional territorial focus more towards the sea. The PLAN’s ambitious ventures into the Indian Ocean is not a new topic in such forums. China has been expanding its influence in the Indo-Pacific region, spanning from the East China Sea through the South China Sea, into the Indian Ocean to Djibouti.

Even though no major maritime infrastructure has been built in the Maldives by China to qualify it as a ‘pearl’ strategists think otherwise. It is believed the Chinese may actually use the backdrop of soft-power measures to gain leverage for potential military intent in the future.

Is this true? Could the Chinese have or even benefit from a naval presence in Maldives? And will the government of Maldives embrace Chinese military presence in the country?

To rectify the question of whether China could use its soft-power on Maldives to expand into the Indian Ocean may be a complex one to untangle. Theoretically speaking, soft-power is the mechanism employed by most developed and even developing nations to project their power over other nations. This may include, but is not limited to, financial loans, aid grants, and even expansion of cultural ties through interactions at varying levels.

Soft-power can be used as a pretext in diplomacy by providing so much aid to the receiver, that when the donor asks for a favor, the receiver may not have much of a bargaining capability. The whole idea is to increase the dependency of as many recipient nations as possible towards the donor state. In the developing world this tactic is not only employed by China, but India is also known to engage in soft-power diplomacy.

Until recently, India has accounted for most of Maldives’ foreign grants, but as of 2014 it was taken over by China. In 2015, the Chinese started building a bridge in Maldives, between the capital Male’ and the airport island of Hulhule. The cost of the bridge is estimated at USD $300 million. This and many more development projects are on the upswing in the Maldives through Chinese aid. Are all these soft-power measures unto Maldives because of a strategic value for China?

Unfolding the drawing board of the ‘String of Pearls’, the Chinese already have developed ports in Sitwe, Chittagong, Hambantota, and in Gwadar while a port in Djibouti is also being developed. Does building a port in Maldives have significance for China?

Looking into this picture through a strategic scope, the Maldives remains in the security grid of India, the latter being the net security provider for the region. Any conventional threat towards India from the soil of Maldives will take moments for Indian forces to respond and neutralize.

Maldives also remains under the surveillance grid of India, making any potential act of aggression from within the Maldives a challenge. The two countries have strong military ties resulting in a number of interactions at multiple levels. These includes security cooperation agreements, joint military exercises, and joint military operations.

The Chinese have already invested in a deep-sea port in the proximity of Maldives, which is the port in Hambantota. Strategists believe this port may be used as a naval base by the PLAN in the future. Investing in another port a few hundred miles apart may not serve as a feasible option for China. Furthermore, Chinese officials have also downplayed any plans to establish a naval base in Maldives.

Taking all this into account, one may not be wise to test India’s tolerance if either Sri Lanka or Maldives decides to permanently provide bases for PLAN. Even if a port is built in Maldives by China, the possibility is that it would be utilised as an operation turn-around (OTR) base by the PLAN.

Finally, would the Maldives ally with an extra-regional power against India? To deliberate on this question, President Yameen, during his address on the Armed Forces Day celebrations in 2014, emphasized his averseness to any extra-regional military foothold in the Indian Ocean region.

Regardless of the statement, in 2015 September, a huge media furor broke out when Maldives revised its constitution with regards to foreign land acquisition. Media disregarded the fact that one of the revised articles, article 302, states that land can only be acquired for investments over a billion dollars, which can be translated as high-end economic investments. Despite this, Maldives was accused by foreign media of paving the way for the Chinese military.

Eventually, Maldives attempted to calm the fears of its neighbors by exchanging diplomatic visits in the process, clearly expressing that Maldives had no intention of destabilizing the region. If one actually looks at the history of Maldives, it did not fare too well with the British after a base in the southern atoll of Addu was provided to RAF in 1941. The eventual independence of Maldives was centered on the agreed evacuation of this RAF base. It would be incongruous for Maldives to get tangled in such a mess again.

Even though the Chinese have embarked on a renewed aggressive aid mechanism in the Maldives, it is still unlikely to hinder Indian footprints in the Maldives, definitely not in the near future. Indian military, social, and economic engagements in Maldives will still out-weigh any extra-regional power for years to come.

As a sovereign state, the Maldives has every right to pursue economic opportunities and other interests from regional or extra-regional donors and partners. As the competition over the control of the Indian Ocean intensifies, a daunting task remains for the leadership of Maldives and its diplomats to responsibly balance the power plays of India and China. The existing rhetoric of an ‘Indophobic’ Maldives does not seem to bear any substantive overt evidence. Rather, Maldives is seen to pursue a path of favoring none over the other.

Major Ahmed Mujuthaba is a career Coast Guard officer in the Maldives National Defence Force. He has served as the Operations Officer of Coast Guard and as the Desk Officer for India at the Ministry of Defence and National Security. He is specialized in salvage diving from the PLAN Submarine Academy, Qingdao and is also a graduate of the Indian Defence Services Staff College, Wellington. You can follow him on Twitter: @mujuthaba.

The views and opinions expressed are his own and do not reflect those of the Maldives National Defence Force or the Government of Maldives.

Featured Image: Malé, the capital of the Maldives.