By Captain Hans Lynch and Dr. Sam Taylor

Introduction

“The mine issues no official communique.” – Adm. William V. Pratt

Mines are one of the most simple – and deadly – asymmetric weapons that can be employed to disrupt naval operations. Their ease of deployment and the danger they pose to warships is only compounded by the challenges associated with finding and destroying them. They are truly the weapons that wait.

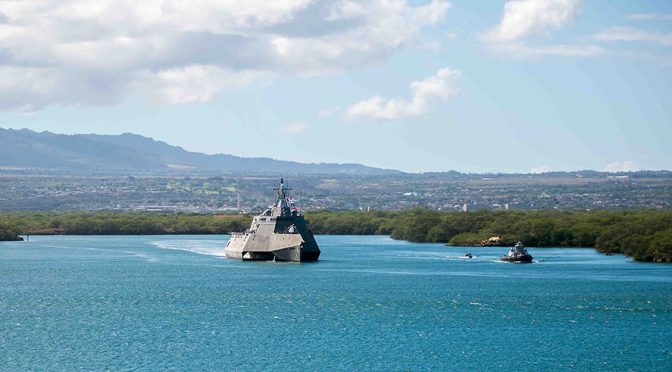

Mine Countermeasures (MCM) is arguably one of the most dirty and dangerous of all naval missions to successfully prosecute. Of the 19 U.S. Navy ships seriously damaged or sunk since World War II, 15 are the direct result of hitting mines. Today, however, the U.S. Navy is entering a new era in MCM as the strategy, techniques, organization, and technology that have long underpinned this mission are all undergoing a renaissance. The Navy’s long-held goal of deploying modular, flexible MCM capabilities is finally becoming an operational reality. This is the new era of the modular MCM force.

Pacing the Mine Warfare Threat

Mines are a growing operational concern as they proliferate in the naval arsenals of potential adversary nations. Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea, to name just a few, all maintain robust inventories of mines and the sophistication of these weapons continues to grow. Mines are no longer the awkward-looking spiked devices bobbing on the ocean’s surface as depicted in photos and newsreels from World Wars I and II. Today, mines are highly advanced and come in many different varieties ranging from bottom-buried mines, to acoustically-actuated variants, to mines manufactured from composite materials. All of these advancements are designed to make ocean mine detection even more challenging.

For far too long the MCM mission and its specialized organization of ships, personnel, and systems have essentially operated as a force separate and apart from the larger Navy. Over the last 20-25 years, the Navy invested in a dedicated fleet of Avenger-class MCM ships (most are permanently forward deployed in Japan and Bahrain), a dedicated fleet of MH-53E Sea Dragon minehunting helicopters, and the development and training of highly-specialized units of divers, explosive ordnance technicians, and marine mammals.

This force and its specialized equipment set were optimized for the less dangerous immediate post-Cold War era, a time which is rapidly receding into history as we witness the return of great power competition as detailed in the National Defense Strategy (NDS). Naval operations are undergoing a fundamental change today due in large part to a renewed emphasis on sea control via distributed maritime operations. These distributed operating concepts will require new force constructs.

A Modular MCM Force Construct

As CNO Admiral John Richardson’s Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority emphasizes, the Navy must “reexamine our approaches in every aspect of our operations.” The MCM force must provide a more lethal and widely distributed capability rather than the concentrated specialization that is the status quo. This has long been an enduring goal of the Navy’s MCM forces, but this bold vision outstripped the technological maturity of the MCM systems then under development to fully execute that goal. Today however, the gap between technology and vision is rapidly narrowing due primarily to the broad application of the concept of modularity across the entire MCM force.

Modularity has become much more than just a key performance feature of the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) and its dedicated MCM mission package. Modularity in today’s Navy transcends LCS by bringing the Fleet the operational benefit of deploying the systems and capabilities that comprise the “full up” MCM mission package. Discrete MCM capabilities can be individually distributed across vessels of opportunity for unique missions and operational scenarios. This modularity will be a critical enabler in helping speed the transformation of Navy MCM into a highly distributed and versatile mission force. This will increase operational unpredictability, which is a key attribute that the NDS is seeking to inject in all military forces going forward.

Central to this transformation is the implementation of an adaptive modular force design for MCM. Under this concept, the Navy or fleet commanders can tailor MCM capabilities to specific regions or numbered fleets based on specific threats or evolving military issues. Embedded in the approach is the idea of forward deploying and distributing MCM capabilities across a wider variety of naval platforms or sites ashore. Borrowing from the operational playbook long used by the Navy’s amphibious ships, the modular MCM force construct frees MCM capabilities from being strictly tied to specific ship types and breaks the one-size-fits-all concept of operational MCM employment.

Using the modular force model, an MCM aviation detachment could be deployed with an Amphibious Ready Group, for example, while a DDG-51 Arleigh Burke-class destroyer deploys with an unmanned minehunting system like Knifefish. The net operational benefit of this concept change is to both increase the overall number of MCM systems in the Fleet at any one time and also ensures MCM systems are distributed across a wider variety and types of naval platforms.

Obviously, serious issues regarding training, personnel assignments, and shipboard maintenance of this new modular MCM force model will have to be assiduously addressed in coming years. Critical questions such as what is the right mix of onboard ship crew support for MCM versus a cadre of EOD that might just deploy to execute a single mission will have to be rigorously verified through at-sea testing and amended as necessary. Other logistical issues include the level of onboard maintenance required to fully support MCM equipment and the types of additional training certifications required for the ship’s crew to capably operate MCM systems. The implementation and sustainment of a robust training, experimentation, and exercise program for MCM will help to resolve many issues and reveal novel solutions to questions that arise as the modular MCM force concept becomes an integral part of the Navy.

Modular Tools and Systems

The Navy plans for the LCS with its embarked MCM mission package to replace the entire Avenger-class of dedicated MCM ships along with the service’s inventory of mine warfare helicopters. Both of these platforms and their associated systems and spare parts inventories are rapidly aging and their overall operational effectiveness is declining. The Navy is investing additional funding in these ships and helicopters beginning in the FY 2018 budget to ensure these legacy MCM assets remain fully capable until replaced by LCS.

The LCS MCM mission package brings a full complement of new MCM capabilities to sea ranging from detection to neutralization, representing a true paradigm shift in MCM operations. Making much greater operational use of unmanned air, surface, subsurface systems, and helicopters equipped with a new suite of MCM equipment, deployed naval forces can more effectively conduct MCM missions without having to sail ships and sailors directly into the dangerous waters of a minefield to prosecute the mission. The more lethal modular MCM force features the LCS MCM mission package combined with the unmatched expertise of the service’s Explosive Ordnance Disposal Units and Expeditionary MCM (ExMCM) Companies. Together this integrated force will be the Navy’s “full-up round” for prosecuting MCM in the years ahead. Current plans call for the Navy to procure 24 MCM mission packages in total and 8 ExMCM Companies.

The initial fielding of new MCM capabilities to the fleet and the latest test successes from emerging developmental systems offer a glimpse into the MCM vision that will emerge into full operational reality over the next decade. Already the Navy’s Program Executive Office for Unmanned and Small Combatants (PEO USC) has delivered the Initial Operational Capability increments of new aviation-based MCM capabilities. This list includes the Airborne Laser Mine Detection System (ALMDS); the Airborne Mine Neutralization System (AMNS); and the Coastal Battlefield Reconnaissance and Analysis (COBRA) system. All of these systems bring a significant leap in MCM capability.

ALMDS and AMNS underwent a multi-phase Operational Assessment (OA) as prescribed by the Navy’s Operational Test and Evaluation Force in 2014. After successfully passing these initial test assessments, ALMDS and AMNS also completed the more formal TECHEVAL phase in 2015. In TECHEVAL the airborne MCM systems were operated by LCS sailors and aviators. ALMDS successfully executed all of its missions, and the Fleet was able to plan, execute, and evaluate the full ALMDS mission sequence while conducting operations on board USS Independence (LCS 2). AMNS also performed well and exceeded the test requirement for mission success. COBRA completed land-based operational testing and is trending to be operationally effective and suitable based on current data analysis. All three of these systems represent the first wave of new MCM capabilities designed to enhance fleet MCM operations and are well-suited to implement the Modular MCM force concept across the Navy.

A new generation of Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USVs) and Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs) are now in the advanced development and testing phases. Initial test assessments are very promising, and these systems will bring more capability and additional mission flexibility to future Modular MCM operations. Some of the key efforts in this advanced development area are the Unmanned Influence Sweep System (UISS), the MCM USV towing the AN/AQS-20 sonar, and the Knifefish UUV.

UISS consists of the MCM USV towing the Mk 104 sweep system and magnetic cable. The MCM USV emerged following the Navy’s decision to cancel the Remote Multi-Mission Vehicle. The MCM USV’s modular payload bay will enable the system to use other payloads as required as future threats and tactics change. Ocean testing of the UISS has already exceeded 600 hours, and the system is on track and on schedule. The MCM USV will also be integrated with the AN/AQS-20C sonar, enabling the detection of bottom, close-tethered, and volume mines. It represents the innovative adaptation of two existing programs to create a completely new MCM capability and is an example of the power of modularity.

Knifefish provides the Navy a new capability to hunt for bottom, volume, and buried mines in ocean waters that are highly cluttered. The system consists of two UUVs equipped with Low Frequency Broadband (LFBB) sonars. The Knifefish minehunting capability is based on the LFBB sonar technology developed by the Office of Naval Research/Naval Research Laboratory to detect and identify very challenging buried mines. LFBB exploits mine signatures to detect and classify mines with significantly lower false alarm rates than traditional minehunting systems using standard acoustic imagery methods.

To meet urgent Fleet requirements new MCM capabilities are already deployed at sea today. Responding to 5th Fleet operational needs in the Arabian Sea, PEO USC catalyzed the development and deployment of four unmanned minehunting units (MHUs). An MHU consists of an unmanned version of the Navy’s standard 11-meter Rigid Hull Inflatable Boat (RHIB), integrated with the AN/AQS-24B mine sonar. The MHUs have been employed from a number of different platform types including the USS Ponce, USNS Catawba, RFA Cardigan Bay, RFA Diligence, a U.S. Army Landing Craft Utility, from ashore, and most recently, the new expeditionary mobile base USS Lewis B. Puller. The MHU effort accelerated the fielding of emerging MCM systems to the fleet. The operational experience gained and lessons learned from employing the MHUs from a variety of platforms is proving invaluable in reducing the developmental risk across other emerging MCM systems like UISS and the MCM USV with minehunting.

Conclusion

In a mission area where an overall lack of capacity has long been as much of a hurdle as capability, the mission flexibility offered by modular force packages – whether legacy systems, the latest in unmanned technology, or a combination of both – is a sound developmental choice. As the National Defense Strategy clearly states, “We cannot expect success fighting tomorrow’s conflicts with yesterday’s weapons or equipment.” Across the MCM kill chain and throughout the entire water column, commanders must have the ability to pick and choose the specific mix of MCM capabilities best suited to the immediate mission. After years of development and rigorous testing, the operational advances promised by LCS and the MCM mission package are becoming a reality. But the rest of the Navy will be better served by embracing a modular mentality that allows for the full range of available MCM capabilities to be employed in far more varied ways and from a broad array of different platforms and warships. The era of the modular MCM force is just beginning.

Captain Hans Lynch is the Mine Warfare Branch Head at OPNAV N952. Dr. Sam Taylor is Mine Warfare Senior Leader, Program Executive Office, Unmanned and Small Combatants (PEO USC).

Featured Image: ARABIAN GULF (May 2, 2015) Sailors assigned to Commander, Task Group (CTG) 56.1 unload an underwater unmanned vehicle from a rigid-hull inflatable boat during mine countermeasures training operations aboard the Afloat Forward Staging Base (Interim) USS Ponce (AFSB(I)-15). CTG 56.1 conducts mine countermeasures, explosive ordnance disposal, salvage-diving, and force protection operations throughout the U.S. 5th Fleet area of operations. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Joshua Bryce Bruns/Released)