By Alex Calvo

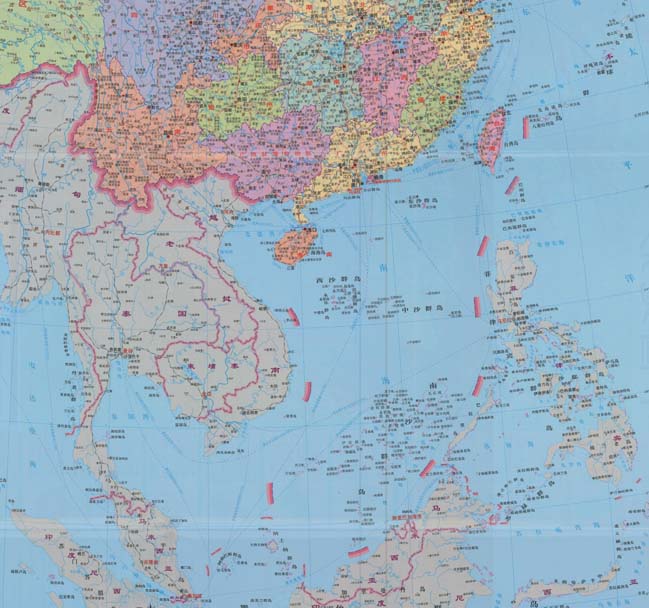

This is the fifth installment in a five-part series summarizing and commenting the 5 December 2014 US Department of State “Limits in the Seas” issue explaining the different ways in which one may interpret Chinese maritime claims in the South China Sea. It is a long-standing US policy to try to get China to frame her maritime claims in terms of UNCLOS. Read part one, part two, part three, part four.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

Whereas the assertion that China has not actually made a claim may not be shared by everybody, in particular given the language flowing from Beijing which the DOS report itself cites, the reference to the “high seas” between mainland China and some islands seems stronger proof that Beijing was not making a historic claim. However, we must again stress that this would be the case if we followed the prevailing interpretation of the law of the sea, but there is no reason why China should adhere strictly to it, and even less that Beijing should not have changed her mind since 1958, when she had little more than a coastal navy and her economy was closed and in tatters. It may be true, as the report notes, that the 1958 Declaration only made a historic claim to the Bohai (Pohai) gulf in northeastern China, but again this should perhaps be judged from a wider historical perspective. After 1949 the PRC took a much more uncompromising stance concerning its North-East than its South-East (and wider maritime) borders. With a pragmatic arrangement in place with the United Kingdom concerning Hong Kong, and a strong economic and political relation with the Soviet Union, it was at the other end of the country where, in 1950, Beijing (not without an intense internal debate given the state of the country), decided to resort to force to prevent the presence of hostile forces close to her border, intervening in the Korean War, pushing back the advancing Allied forces and reversing the impact of the Inchon landing, ultimately forcing a stalemate on the ground. In 1958, just five years after the Korean armistice, nearby waters may have thus been much more present in Chinese leaders’ minds. In addition, these were also the waters directly leading to Tianjin and Beijing, the venue for foreign interventions in both the Opium Wars and the Taiping Rebellion. It would not be until the late 1970s that China’s South-Eastern flank would begin to receive more attention, in part thanks to the rapprochement with the United States and in particular once economic growth and the country’s move to become a net energy and commodity importer turned the waters of the South China Sea into a vital venue and potential choke point. It is true that in December 1941 the loss of HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse in the South China Sea had enabled the Japanese to land in Malaya and ultimately conquer Burma, closing the last land route to besieged Nationalist China, but this did not result in a comparable imprint on China’s historical consciousness, among other reasons because the episode did not involve Chinese naval forces and was subsumed into a much larger, dramatic, and quickly-developing picture.

Rejecting the validity of a possible historic claim by China. Concerning whether, if China “Made a Historic Claim”, it would “have Validity”, the DOS paper insists that “such a claim would be contrary to international law”, stressing the limited degree to which UNCLOS recognizes this category of claims, as evidenced by its “text and drafting history”. The text argues that “apart from a narrow category of near-shore ‘historic’ bays” in Article 10, and “historic title” concerning “territorial sea boundary delimitation (Article 15)”, “modern international law of the sea does not recognize history as the basis for maritime jurisdiction”, citing the Gulf of Maine ICJ case. It also underlines the fact that UNCLOS provisions concerning the EEZ, continental shelf, and the high seas “do not contain any exceptions for historic claims” to the detriment of coastal states and all estates enjoying certain freedoms. Concerning fisheries, the report acknowledges that UNCLOS refers to “the need to minimize economic dislocation in States whose nationals have habitually fished” in the EEZ (Article 62(3)) and to “traditional fishing rights and other legitimate activities” (Article 51), but restricts the impact to the possible granting by one state to another of fisheries resources “based on prior usage”. The text stresses that no such traditional fishing practices can “provide a basis for sovereignty, sovereignty rights, or jurisdiction,” adding that UNCLOS rules on oil and gas development contain no “exception for historic rights in any context.” Again we note how a purely legal report like this may be missing part of the picture, given the great importance that fishing vessels have in the ongoing conflict over the South China Sea, where they are one of the pillars of asymmetric naval warfare.

Chinese scholars Gao and Jia have argued that UNCLOS does not regulate “historic title” and “historic rights,” which fall instead under the purview of general international law. In their view, UNCLOS “was never intended, even at the time of its adoption, to exhaust international law. On the contrary, it has provided ample room for customary law to develop and to fill in the gaps that the Convention itself was unable to fill in 1982” as clear from its preamble, which reads “matters not regulated by this Convention continue to be governed by the rules and principles of general international law.” The DOS report explicitly rejects this position, saying that “it is not supported by international law” and goes against the “comprehensive scope of the LOS Convention.” Experts like Mark Valencia, on the other hand, hold that China’s posture may be compatible with the international law of the sea.

The text does not stop at arguing that it is not open to a state to make historic claims based not on UNCLOS but on general international law, laying down a second line of defense. It explains that, “even assuming that a Chinese historic claim in the South China Sea were governed by ‘general international law’ rather than the Convention,” it would still be invalid since it would not meet the necessary requirements under general international law, namely “open, notorious, and effective exercise of authority over the South China Sea,” plus “continuous exercise of authority” in those waters and “acquiescence by foreign States” in such exercise of authority. Furthermore, it explains that the United States, which “is active in protesting historic claims around the world that it deems excessive,” has not protested “the dashed line on these grounds, because it does not believe that such a claim has been made by China,” with Washington choosing instead to request a clarification of the claim. Whether this view is also meant to avoid a frontal clash with Beijing, in line with the often state policy goal of “managing” rather than “containing” China’s rise, is something not discussed in the text.

The report concludes by criticizing another view put forward by Gao and Jia, namely the relevance of claims made before the advent of UNCLOS. While these two scholars argue that “In the case of the South China Sea as enclosed by the nine-dash line, China’s historic title and rights, which preceded the advent of UNCLOS by many years, have a continuing role to play,” the DOS paper says that “The fact that China’s claims predate the LOS Convention does not provide a basis under the Convention or international law for derogating from the LOS Convention,” adding that “permitting States to derogate from the provisions of the Convention because their claims pre-date its adoption is contrary to and would undermine” the convention’s “object and purpose” stated in its preamble to “settle … all issues relating to the law of the sea.”

Conclusions. Long-standing American policy towards China stresses the need to manage the latter’s rise, so that it does not threaten the post-Second World War system, based among others on freedom of navigation and a ban on territorial expansion as a legitimate causus belli. As a result, Washington has often called on Beijing to clarify her claims on the South China Sea, in an attempt to constrain them while avoiding a frontal clash. This position also seeks to reinforce the perception that the United States focuses on the rule of law at sea, rather than on supporting one claimant against the other over disputed waters. The DOS document, in line with this approach, carefully dissects Chinese claims, analyzing whether they may be compatible with standard American interpretations of international Law of the Sea. The conclusions are rather pessimistic, exposing how, despite having ratified UNCLOS, the Convention’s provisions are not seen in the same light by Beijing and Washington. This should not surprise us, since international law seeks to constrain power but at the same time it is shaped by it, thus as countries rise they seek to play a greater role in the fate of rules and principles. In the case of China this is even clearer due to historical perceptions that it was to a large extent seaborne power which subjected the country to a semi-colonial status for a whole century. If Beijing’s claims in the South Chinese Sea cannot be seen in the light of UNCLOS, the question arises what ultimate Chinese goals are. Could this be the subject of a future paper by the Department of State? Or does Washington prefer to wait until the international arbitration case launched by Manila concludes? While the second option seems more likely, as time goes by the idea that China’s rise may be shaped, rather than constrained, increasingly seems less and less realistic. However, if the time comes to draw a line in the sand, a whole of government effort will be needed, going beyond the naval circles that to date have been most vocal in articulating the need to resist Chinese expansion.

Alex Calvo is a guest professor at Nagoya University (Japan) focusing on security and defence policy, international law, and military history in the Indian-Pacific Ocean. Region. A member of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC) and Taiwan’s South China Sea Think-Tank, he is currently writing a book about Asia’s role and contribution to the Allied victory in the Great War. He tweets @Alex__Calvo and his work can be found here.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]