By Travis Howard and José de Arimatéia da Cruz

Introduction

The United States Navy is a vast, worldwide organization with unique missions and challenges, with information security (and information warfare at large) a key priority within the Chief of Naval Operations’ strategic design. With over 320,000 active duty personnel, 274 ships with over 20 percent of them deployed across the world at any one time, the Navy’s ability to securely communicate across the globe to its forces is crucial to its mission. In this age of rapid technological growth and the ever expanding internet of things, information security is a primary consideration in the minds of senior leadership of every global organization. The Navy is no different, and success or failure impacts far more than a stock price.

Indeed, an entire sub-community of professional officers and enlisted personnel are dedicated to this domain of information warfare. The great warrior-philosopher Sun Tzu said “one who knows the enemy and knows himself will not be endangered in a hundred engagements.” The Navy must understand the enemy, but also understand its own limitations and vulnerabilities, and develop suitable strategies to combat them. Thankfully, strategy and policy are core competencies of military leadership, and although information warfare may be replete with new technology, it conceptually remains warfare and thus can be understood, adapted, and exploited by the military mind.

This paper presents a high-level, unclassified overview of threats and vulnerabilities surrounding the U.S. Navy’s network systems and operations in cyberspace. Several threats are identified to include nation states, non-state actors, and insider threats. Additionally, vulnerabilities are presented such as outdated network infrastructure, unique networking challenges present aboard ships at sea, and inadequate operating practices. Technical security measures that the Navy uses to thwart these threats and mitigate these vulnerabilities are also presented. Current U.S. Navy information security policies are analyzed, and a potential security strategy is presented that better protects the fleet from the before-mentioned cyber threats, mitigates vulnerabilities, and aligns with current federal government mandates.

Navy Network Threats and Vulnerabilities

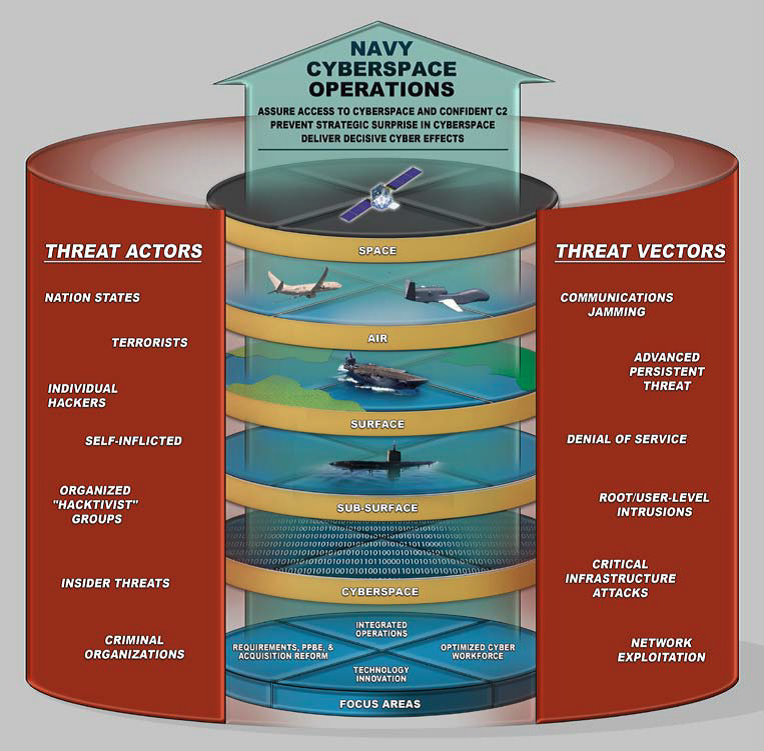

There are several cyber threats that the Navy continues to face when conducting information operations in cyberspace. Attacks against DoD networks are relentless, with 30 million known malicious intrusions occurring on DoD networks over a ten-month period in 2015. Of principal importance to the U.S. intelligence apparatus are nation states that conduct espionage against U.S. interests. In cyberspace, the Navy contests with rival nations such as Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea, and all are developing their own information warfare capabilities and information dominance strategies. These nations, still in various stages of competency in the information warfare domain, continue to show interest in exploiting the Navy’s networks to conduct espionage operations, either by stealing information and technical data on fleet operations or preventing the Navy from taking advantage of information capabilities.

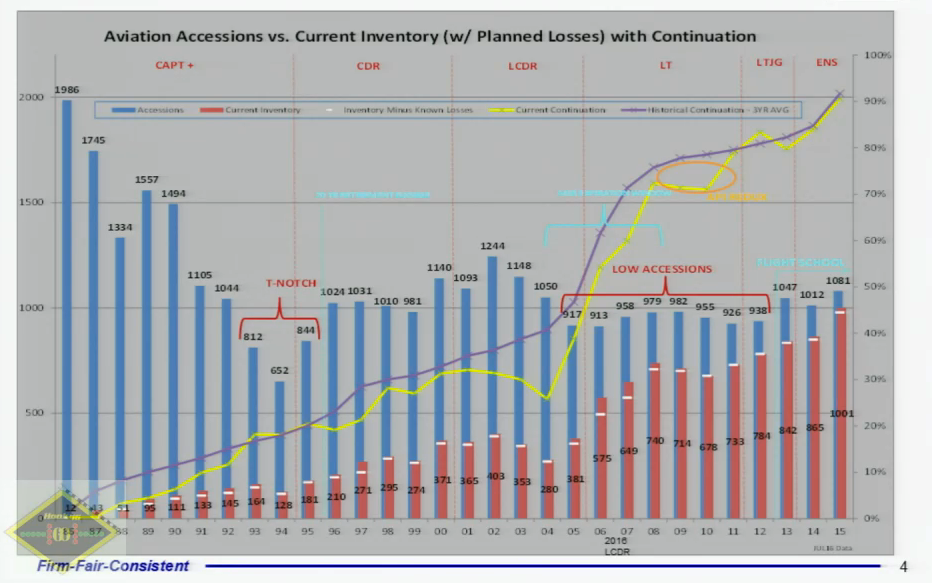

Non-state actors also threaten naval networks. Organized activist groups known collectively as “hacktivists,” with no centralized command and control structure and dubious, fickle motivations, present a threat to naval cyberspace operations if their goals are properly aligned. In 2012, Navy officials discovered hacktivists from the group “Team Digi7al” had infiltrated the Navy’s Smart Web Move website, extracting personal data from almost 220,000 service members, and has been accused of more than two dozen additional attacks on government systems from 2012 to 2013. The hactivist group boasted of their exploits over social media, citing political reasons but also indicated they did it for recreation as well. Individual hackers, criminal organizations, and terrorist groups are also non-state threat actors, seeking to probe naval networks for vulnerabilities that can be exploited to their own ends. All of these threats, state or non-state actors, follow what the Department of Defense (DoD) calls the “cyber kill chain,” depicted in figure 1. Once objectives are defined, the attacker follows the general framework from discovery to probing, penetrating then escalating user privileges, expanding their attack, persisting through defenses, finally executing their exploit to achieve their objective.

One of the Navy’s most closely-watched threat sources is the insider threat. Liang and Biros, researchers at Oklahoma State University, define this threat as “an insider’s action that puts an organization or its resources at risk.” This is a broad definition but adequately captures the scope, as an insider could be either malicious (unlikely but possible, with recent examples) or unintentional (more likely and often overlooked).

The previously-mentioned Team Digi7al hactivist group’s leader was discovered to be a U.S. Navy enlisted Sailor, Petty Officer Nicholas Knight, a system administrator within the reactor department aboard USS HARRY S TRUMAN (CVN 75). Knight used his inside knowledge of Navy and government systems to his group’s benefit, and was apprehended in 2013 by the Navy Criminal Investigative Service and later sentenced to 24 months in prison and a dishonorable discharge from Naval service.

Presidential Executive Order 13587, signed in 2011 to improve federal classified network security, further defines an insider threat as “a person with authorized access who uses that access to harm national security.” Malevolence aside, the insider threat is particularly perilous because these actors, by virtue of their position within the organization, have already bypassed many of the technical controls and cyber defenses that are designed to defeat external threats. These insiders can cause irreparable harm to national security and the Navy’s interests in cyberspace. This has been demonstrated by the Walker-Whitworth espionage case in the 1980s, Private Manning in the latter 2000s, or the very recent Edward Snowden/NSA disclosure incidents.

The Navy’s vulnerabilities, both inherent to its nature and as a result of its technological advances, are likewise troubling. In his 2016 strategic design, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John M. Richardson stated that “the forces at play in the maritime system, the force of the information system, and the force of technology entering the environment – and the interplay between them have profound implications for the United States Navy.” Without going into classified details or technical errata, the Navy’s efforts to secure its networks are continuously hampered by a number of factors which allow these threats a broad attack surface from which to choose.

As the previous Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), Admiral Jon Greenert describes in 2012, Navy platforms depend on networked systems for command and control: “Practically all major systems on ships, aircraft, submarines, and unmanned vehicles are ‘networked’ to some degree.” The continual reliance on position, navigation, and timing (PNT) systems, such as the spoofing and jamming-vulnerable Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite constellation for navigation and precision weapons, is likewise a technical vulnerability. An internet search on this subject reveals multiple scholarly and journalist works on these vulnerabilities, and more than a few describe how to exploit them for very little financial investment, making them potentially cheap attack vectors.

Even the Navy’s vast size and scope of its networks present a vulnerability to its interests in cyberspace. As of 2006, the Navy and Marine Corps Intranet (NMCI), a Government Owned-Contractor Operated (GOCO) network that connects Navy and Marine Corps CONUS shore commands under a centralized architecture, is “the world’s largest, most secure private network serving more than 500,000 sailors and marines globally.” That number has likely grown in the 10 years since that statistic was published, and even though the name has been changed to the Navy’s Next Generation Network (NGEN), it is still the same large beast it was before, and remains one of the single largest network architectures operating worldwide. Such a network provides an enticing target.

Technical Security Measures and Controls

The Navy employs the full litany of technical cybersecurity controls across the naval network enterprise, afloat and ashore. Technical controls include host level protection through the use of McAfee’s Host Based Security System (HBSS), designed specifically for the Navy to provide technical controls at the host (workstation and server) level. Network controls include network firewalls, intrusion detection and prevention systems (IDS/IPS), security information and event management, continuous monitoring, boundary protection, and defense-in-depth functional implementation architecture. Anti-virus protection is enabled on all host systems through McAfee Anti-Virus, built into HBSS, and Symantec Anti-Virus for servers. Additionally, the Navy employs a robust vulnerability scanning and remediation program, requiring all Navy units to conduct a “scan-patch-scan” rhythm on a monthly basis, although many units conduct these scans weekly.

The Navy’s engineering organization for developing and implementing cybersecurity technical controls to combat the cyber kill chain in figure 1 is the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command (SPAWAR), currently led by Rear Admiral David Lewis, and earlier this year SPAWAR released eight technical standards that define how the Navy will implement technical solutions such as firewalls, demilitarized zones (DMZs), and vulnerability scanners. RADM Lewis noted that 38 standards will eventually be developed by 2018, containing almost 1,000 different technical controls that must be implemented across the enterprise.

Of significance in this new technical control scheme is that no single control has priority over the others. All defensive measures work in tandem to defeat the adversary’s cyber kill chain, preventing them from moving “to the right” without the Navy’s ability to detect, localize, contain, and counter-attack. RADM Lewis notes that “the key is defining interfaces between systems and collections of systems called enclaves,” while also using “open architecture” systems moving forward to ensure all components speak the same language and can communicate throughout the enterprise.

The importance of open systems architecture (OSA) as a way to build a defendable network the size of the Navy’s cannot be understated. The DoD and the Navy, in particular, have mandated use of open systems specifications since 1994; systems that “employ modular design, use widely supported and consensus-based standards for their key interfaces, and have been subjected to successful validation and verification tests to ensure the openness of their key interfaces.” By using OSA as a means to build networked systems, the Navy can layer defensive capabilities on top of them and integrate existing cybersecurity controls more seamlessly. Proprietary systems, by comparison, lack such flexibility thereby making integration into existing architecture more difficult.

Technical controls for combating the insider threat become more difficult, often revolving around identity management software and access control measures. Liang and Biros note two organizational factors to influencing insider threats: security policy and organizational culture. Employment of the policy must be clearly and easily understood by the workforce, and the policy must be enforced (more importantly, the workforce must fully understand through example that the policies are enforced). Organizational culture centers around the acceptance of the policy throughout the workforce, management’s support of the policy, and security awareness by all personnel. Liang and Biros also note that access control and monitoring are two must-have technical security controls, and as previously discussed, the Navy clearly has both yet the insider threat remains a primary concern. Clearly, more must be done at the organizational level to combat this threat, rather than just technical implementation of access controls and activity monitoring systems.

Information Security Policy Needed to Address Threats and Vulnerabilities

The U.S. Navy has had an information security policy in place for many years, and the latest revision is outlined in Secretary of the Navy Instruction (SECNAVINST) 5510.36, signed June 2006. This instruction is severely out of date and does not keep pace with current technology or best practices; Apple released the first iPhone in 2007, kicking off the smart phone phenomenon that would reach the hands of 68% of all U.S. adults as of 2015, with 45% also owning tablets. Moreover, the policy has a number of inconsistencies and fallacies that can be avoided, such as a requirement that each individual Navy unit establish its own information security policy, which creates unnecessary administrative burden on commands that may not have the time nor expertise to do so. Additionally, the policy includes a number of outdated security controls under older programs such as the DoD Information Assurance Certification and Accreditation Process (DIACAP), which has since transitioned to the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) Risk Management Framework (RMF).

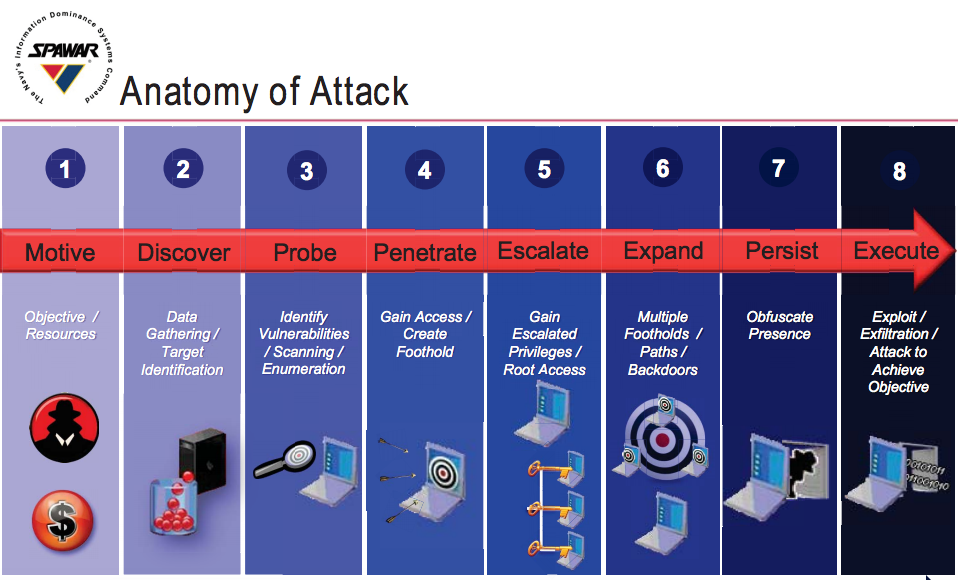

Beginning in 2012, the DoD began transitioning away from DIACAP towards the NIST RMF, making full use of NIST Special Publications (SPs) for policy development and implementation of security controls. The NIST RMF as it applies to DoD, and thus the Navy, is illustrated in figure 2. The process involves using NIST standards (identified in various SPs) to first categorize systems, select appropriate security controls, implement the controls, assess their effectiveness, authorize systems to operate, then monitor their use for process improvement.

This policy is appropriate for military systems, and the Navy in particular, as it allows for a number of advantages for policymakers, warfighters, system owners, and developers alike. It standardizes cybersecurity language and controls across the federal government for DoD and Navy policymakers, and increases rapid implementation of security solutions to accommodate the fluidity of warfighting needs. Additionally, it drives more consistent standards and optimized workflow for risk management which benefits system developers and those responsible for implementation, such as SPAWAR.

Efforts are already underway to implement these policy measures in the Navy, spearheaded by SPAWAR as the Navy’s information technology engineering authority. The Navy also launched a new policy initiative to ensure its afloat units are being fitted with appropriate security controls, known as “CYBERSAFE.” This program will ensure the implementation of NIST security controls will be safe for use aboard ships, and will overall “focus on ship safety, ship combat systems, networked combat and logistics systems” similar to the Navy’s acclaimed SUBSAFE program for submarine systems but with some notable IT-specific differences. CYBERSAFE will categorize systems into three levels of protection, each requiring a different level of cybersecurity controls commensurate with how critical the system is to the Navy’s combat or maritime safety systems, with Grade A (mission critical) requiring the most tightly-controlled component acquisition plan and continuous evaluation throughout the systems’ service life.

Implementation of the NIST RMF and associated security policies is the right choice for the Navy, but it must accelerate its implementation to combat the ever-evolving threat. While the process is already well underway, at great cost and effort to system commands like SPAWAR, these controls cannot be delayed. Implementing the RMF across the Navy enterprise will reduce risk, increase security controls, and put its implementation in the right technical hands rather than a haphazard implementation of an outdated security policy that has, thus far, proven inadequate to meet the threats and reduce vulnerabilities inherent with operating such a large networked enterprise. With the adoption of these new NIST policies also comes a new strategy for combating foes in cyberspace, and the Navy has answered that in a few key strategy publications outlined in the next section.

Potential Security Strategy for Combating Threats and Minimizing Vulnerabilities

It is important to note that the Navy, like the other armed services of the DoD, was “originally founded to project U.S. interests into non-governed common spaces, and both have established organizations to deal with cybersecurity.” The Navy’s cyber policy and strategy arm is U.S. Fleet Cyber Command (FLTCYBERCOM, or FCC), co-located with the DoD’s unified cyber commander, U.S. Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM, or USCC). Additionally, its operational cyber arm, responsible for offensive and defensive operations in cyberspace, is U.S. 10th Fleet (C10F), which is also co-located with U.S. Fleet Cyber and shares the same commander, currently Vice Admiral Michael Gilday.

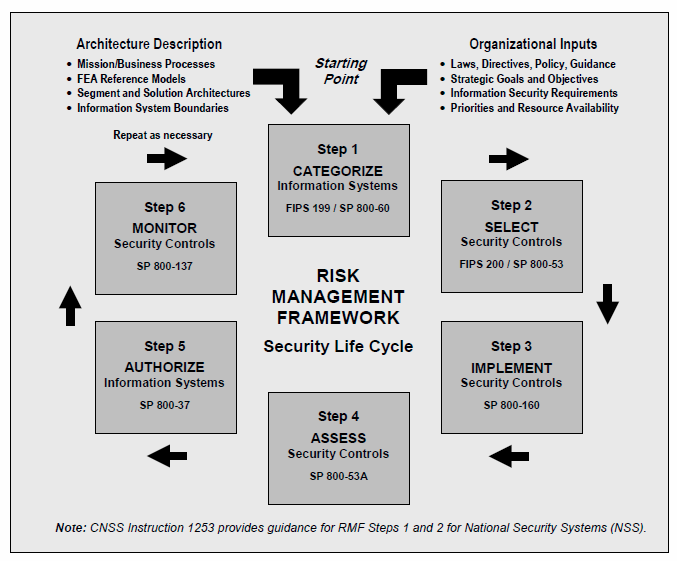

Prior to VADM Gilday’s assumption of command as FCC/C10F, a strategy document was published by the Chief of Naval Operations in 2013 known as Navy Cyber Power 2020, which outlines the Navy’s new strategy for cyberspace operations and combating the threats and vulnerabilities it faces in the information age. The strategic overview is illustrated in figure 3, and attempts to align Navy systems and cybersecurity efforts with four main focus areas: integrated operations, optimized cyber workforce, technology innovation, and acquisition reform. In short, the Navy intends to integrate its offensive and defensive operations with other agencies and federal departments to create a unity of effort (evident by its location at Ft. Meade, MD, along with the National Security Agency and USCC), better recruit and train its cyber workforce, rapidly provide new technological solutions to the fleet, and reform the acquisition process to be more streamlined for information technology and allow faster development of security systems.

Alexander Vacca, in his recent published research into military culture as it applies to cybersecurity, noted that the Navy is heavily influenced by sea combat strategies theorized by Alfred Thayer Mahan, one of the great naval strategists of the 19th century. Indeed, the Navy continually turns to Mahan throughout an officer’s career from the junior midshipman at the Naval Academy to the senior officer at the Naval War College. Vacca noted that the Navy prefers Mahan’s “decisive battle” strategic approach, preferring to project power and dominance rather than pursue a passive, defensive strategy. This potentially indicates the Navy’s preference to adopt a strategy “designed to defeat enemy cyber operations” and that “the U.S. Navy will pay more attention to the defeat of specified threats” in cyberspace rather than embracing cyber deterrence wholesale. Former Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus described the offensive preference for the Navy’s cyberspace operations in early 2015, stating that the Navy was increasing its cyber effects elements in war games and exercises, and developing alternative methods of operating during denial-of-service situations. It is clear, then, that the Navy’s strategy for dealing with its own vulnerabilities is to train to operate without its advanced networked capabilities, should the enemy deny its use. Continuity of operations (COOP) is a major component in any cybersecurity strategy, but for a military operation, COOP becomes essential to remaining flexible in the chaos of warfare.

A recent article describing a recent training conference between top industry cybersecurity experts and DoD officials was critical of the military’s cybersecurity training programs. Chief amongst these criticisms was that the DoD’s training plan and existing policies are too rigid and inflexible to operate in cyberspace, stating that “cyber is all about breaking the rules… if you try to break cyber defense into a series of check-box requirements, you will fail.” The strategic challenge moving forward for the Navy and the DoD as a whole is how to make military cybersecurity policy (historically inflexible and absolute) and training methods more like special forces units: highly trained, specialized, lethal, shadowy, and with greater autonomy within their specialization.

Current training methods within the U.S. Cyber Command’s “Cyber Mission Force” are evolving rapidly, with construction of high-tech cyber warfare training facilities already underway. While not yet nearly as rigorous as special forces-like training (and certainly not focused on the physical fitness aspect of it), the training strategy is clearly moving in a direction that will develop a highly-specialized joint information warfare workforce. Naegele’s article concludes with a resounding thought: “The heart of cyber warfare…is offensive operations. These are essential military skills…which need to be developed and nurtured in order to ensure a sound cyber defense.“

Conclusions

This paper outlined several threats against the U.S. Navy’s networked enterprise, to include nation state cyber-rivals like China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea, and non-state actors such as hactivists, individual hackers, terrorists, and criminal organizations. The insider threat is of particular concern due to this threat’s ability to circumvent established security measures, and requires organizational and cultural influences to counter it, as well as technical access controls and monitoring. Additionally, the Navy has inherent vulnerabilities in the PNT technology used in navigation and weapon systems throughout the fleet, as well as the vast scope of the ashore network known as NMCI, or NGEN.

The Navy implements a litany of cybersecurity technical controls to counter these threats, including firewalls, DMZs, and vulnerability scanning. One of the Navy’s primary anti-access and detection controls is host-based security through McAfee’s HBSS suite, anti-virus scanning, and use of open systems architecture to create additions to its network infrastructure. The Navy, and DoD as a whole, is adopting the NIST Risk Management Framework as its information security policy model, implementing almost 1000 controls adopted from NIST Special Publication 800-53, and employing the RMF process across the entire enterprise. The Navy’s four-pronged strategy for combating threats in cyberspace and reducing its vulnerability footprint involves partnering with other agencies and organizations, revamping its training programs, bringing new technological solutions to the fleet, and reforming its acquisition process. However, great challenges remain in evolving its training regimen and military culture to enable an agile and cyber-lethal warfighter to meet the growing threats.

In the end, the Navy and the entire U.S. military apparatus is designed for warfare and offensive operations. In this way, the military has a tactical advantage over many of its adversaries, as the U.S. military is the best trained and resourced force the world has ever known. General Carl von Clausewitz, in his great anthology on warfare, stated as much in chapter 3 of book 5 of On War (1984), describing relative strength through admission that “the principle of bringing the maximum possible strength to the decisive engagement must therefore rank higher than it did in the past.” The Navy must continue to exploit this strength, using its resources smartly by enacting smart risk management policies, a flexible strategy for combating cyber threats while reducing vulnerabilities, and training its workforce to be the best in the world.

Lieutenant Howard is an information warfare officer/information professional assigned to the staff of the Chief of Naval Operations in Washington D.C. He was previously the Director of Information Systems and Chief Information Security Officer on a WASP-class amphibious assault ship in San Diego.

Dr. da Cruz is a Professor of International Relations and Comparative Politics at Armstrong State University, Savannah, Georgia and Adjunct Research Professor at the U.S. Army War College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

The views expressed here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of the Navy, Department of the Army, Department of Defense or the United States Government.

Featured Image: At sea aboard USS San Jacinto (CG 56) Mar. 5, 2003 — Fire Controlman Joshua L. Tillman along with three other Fire Controlmen, man the shipÕs launch control watch station in the Combat Information Center (CIC) aboard the guided missile cruiser during a Tomahawk Land Attack Missile (TLAM) training exercise. (RELEASED)