How the Mad Foxes of Patrol Squadron FIVE are harnessing their most powerful resource – their people – in an effort to cut inefficiencies and improve productivity.

By Kenneth Flannery with Jared Wilhelm

The U.S. Military Academy’s Modern War Institute recently published a thorough primer by ML Cavanaugh on what it means to drive innovation in the military. The most important takeaway was the large difference between the simple buzzword “innovation,” and the people who actually do the dirty work of driving positive change – oft-cited as “innovation”– within the force: “defense entrepreneurs.” This series focuses on an operational U.S. Navy Maritime Patrol Squadron that is full of defense entrepreneurs, and how their unit is taking the “innovation imperative” from on high and translating it to the deckplate level. Part 1 focuses on the “Why? Who? And How?”; Part 2 reveals observed institutional barriers, challenges, and a how-to that other units could use to adapt the model to their own units.

The Innovation Imperative

Today, the U.S. Navy remains the most powerful seafaring force the world has ever known, but there is nothing destined about that position. To maintain this superior posture, we must find leverage that allows us to maintain an edge over our adversaries. One of our most powerful levers in the past has been our economy. We were once able to maintain supremacy simply by outspending our rivals on research, development and sheer production. While the United States still has the largest military budget of any nation, that budget is increasingly stretched to counter threats in a dizzying array of locales to include the South China Sea, Arabian Gulf, or even an increasingly vulnerable Arctic. Additionally, the rest of the world is catching up economically. Some assessments indicate that China will have the largest economy in the world by 2030 and they are already producing their own domestically-built aircraft carriers. It isn’t just China on our economic heels; by 2050 the United States could have slid to third place behind India as well. Finally, our adversaries’ continual embrace of technological theft and espionage involving some of our most expensive proprietary platforms has shrunk the technological gap that the U.S. enjoyed for multiple decades. These realities make it clear that the U.S. must find a new way to counter opponents besides technological advantage.

Much like the Obama administration’s “Pivot to Asia,” the Department of Defense is experiencing what some might call a “Pivot to Innovation.” Former Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel’s “Defense Innovation Initiative” and “Third Offset Strategy” both signal a reinvigorated focus on maintaining and advancing our military superiority over both unconventional actors and near-peer competitors alike.

In alignment with Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson’s intent, VP-5 is investing time and manpower in the idea that that new counterweight will be the innovative ideas of our Sailors. Just as nuclear weapons and advancements like stealth and Global Positioning Systems kept the U.S. military on top during the conflicts of the Cold War and Post-Cold War eras, it will be our ability to rapidly assess challenges and implement solutions that will guarantee our security in the future. This will require a reimagining of how we currently operate and how we are organized. Our squadron believes the key to this revolution lies with its junior enlisted and junior officer ranks.

Tapping the Innovative Ideas of the Everyday “Doers”

VP-5 is taking a multi-pronged approach to molding an innovation-friendly climate to best tap the ideas of those accomplishing the mission on a daily basis. Patrol Squadron FIVE (VP-5) is currently experimenting with a dedicated Innovation Department in our command structure, but this isn’t the first time that the squadron has embraced change to maintain the technological and fighting advantage over adversaries. The unit is based at the U.S. Navy’s Master Anti-submarine Warfare facility at Naval Air Station Jacksonville, FL, where we became the second squadron Fleet-wide to transition from the P-3C Orion to the P-8A Poseidon aircraft. This successful transition was based on new training and simulation technologies, but also on a rich history that spans from our founding in 1937 to involvement in World War II, Kennedy’s blockade of Cuba during the Cold War, the Balkan Conflict, and our recent involvement in the Middle East. Throughout this time, we have used no less than five different types of Maritime Patrol Aircraft.

Just as the transition in 1948 from the PBY-5A to the PV-2 brought new tools to the squadron’s warfighting capabilities, today we are augmenting the new technologies of the P-8A with a change to our organizational structure and business practices. A traditional operational naval aviation command administers a standard set of departments including Operations, Training, Safety/NATOPS (Standardization), and Maintenance. By implementing a new Innovation Department led by a warfare-qualified pilot or Naval Flight Officer lieutenant (O-3), VP-5 seeks to elevate the innovation construct to a position alongside the traditional departments required for squadron mission accomplishment. In addition to the lieutenant department head, the Innovation group is staffed by an additional lieutenant and a Senior Chief. Its mission statement reads:

“Lead Naval Aviation in accomplishing our mission by sustaining a culture based on process improvement and disruptive thinking. The force that knows the desired outcome, measures progress in real time, and adapts processes to overcome barriers has a sustainable advantage over adversaries who tolerate their deficiencies. Similarly, the force that can innovate transforms the battlespace to their advantage.”

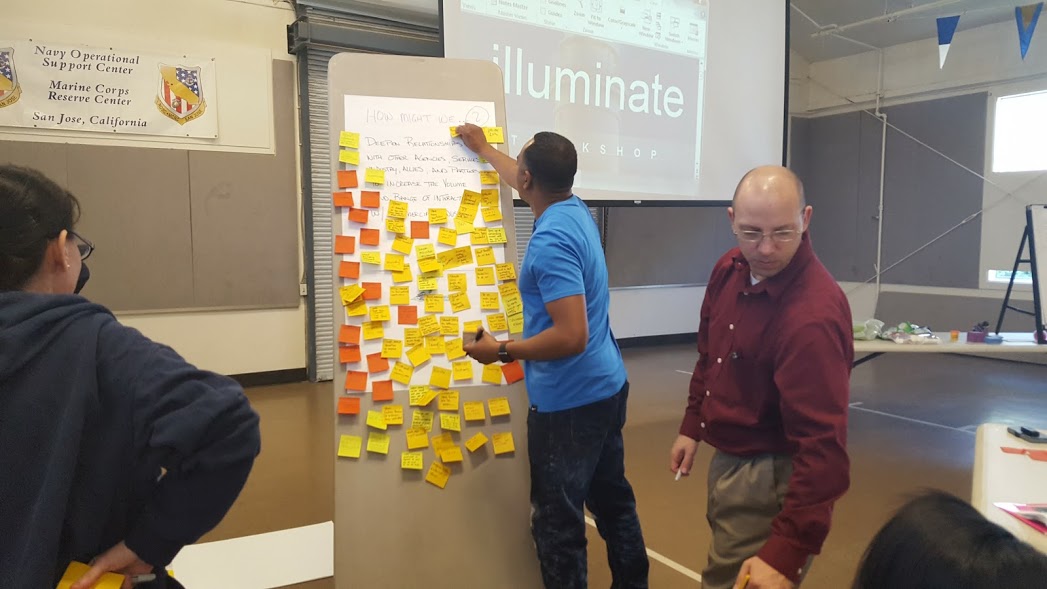

The establishment of the Innovation Department sends a strong signal to the department heads and the senior enlisted that innovation is a priority, but it may not necessarily trickle down to the average junior enlisted Sailor that VP-5 is a different type of squadron. To ensure the culture reaches everyone, we have implemented large “Innovation Whiteboards” throughout the squadron and encourage all members to post ideas and suggestions. Sailors can see what others have posted and leave reactions of their own. Similar to the “CO’s Sticky Note Board” on the USS Benfold (DDG 65), the ideas written on the whiteboards are then compiled for further action by the Innovation Department.

Whether an idea has been generated via a whiteboard or suggested by means of a more traditional route, the next step in the process is to create a “Swarm Cell.” Swarm Cells are small groups of people that aim to rapidly implement solutions to the problem being addressed. These groups follow a predetermined set of procedures that begin with specifying the desired output. Starting with a clear description of the end result discourages the Cell from veering off course or diluting their product with superfluous features that do little to help the original problem. The Swarm Cells then move to address the actual problem or process for which they were created, all the while making sure that their efforts lead them toward the desired output. Next, the Cells measure their progress to decide if the desired output has been achieved. From there, the members of the group can choose to share their knowledge or revisit their solutions if they have determined that they have not met their output goals.

These Swarm Cells are not on an innovation island. The squadron strives to provide support and guidance for those working to realize their ideas and provides each Swarm Cell with an Innovation Accelerator. This Accelerator may be an official member of the Innovation Department, but is not necessarily so. If the Swarm Cell is like the train conductor, deciding the destination and exactly how fast to get there, the Innovation Accelerator is the train track, allowing room for minor deviations, but keeping the train on course to its final goal. Accelerators need not be intimately involved with the minutiae of their Swarm Cells, and as such may be facilitating two or three different Cells concurrently. By asking simple questions the Accelerator can refocus the team:

1. Has the Cell outlined a clearly defined output?

2. Is the Cell working to achieve that vision, or have they allowed distractions to creep in?

3. Are they continually measuring their progress along the way?

Again, in VP-5 innovation belongs to everyone. Sailors of all ranks and pedigrees are encouraged and expected to turn a critical eye to established procedures in an effort to push our squadron into the twenty-first century. However, change for the sake of change is not one of our objectives. To guard against this, the product or design is subjected to an internal Shark Tank once each Swarm Cell is sufficiently satisfied with their work. These Shark Tank events are open to all hands and are designed to prod for weak spots in the proposal and introduce the idea to the whole team. The Swarm Cell’s program or improvement is critiqued from every angle to determine its overall benefit and structural integrity. These sessions are designed to be thorough in order to weed out underdeveloped initiatives or those that may not provide a quantifiable benefit. If a program passes muster, it continues in whatever form is appropriate, whether that is a new or revised squadron instruction or perhaps a meeting further up the chain of command.

Meaningful Results

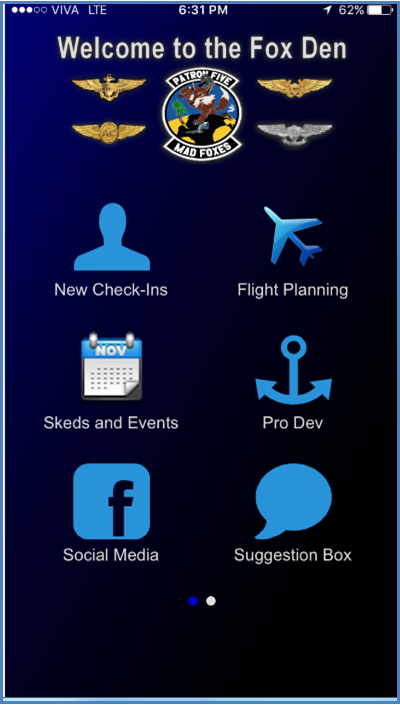

Our modest foray into innovation has already begun to bear fruit. One of the most promising results of the innovation process has been the development of a dedicated command smartphone application called Quarterdeck. What started as a search for a better way to communicate has blossomed into a robust “app” which boasts capability far beyond that which was initially envisioned. Currently available on the Droid and Apple App stores, the application meets or exceeds DoD information assurance requirements and includes features like flight schedule postings and peer-to-peer instant messaging, among many others. Thanks to motivated junior officers who attended the 2016 Aviation Mission Support Tactical Advancements for the Next Generation (TANG) at Defense Innovation Unit Experimental (DIUx) in Silicon Valley, the Adobe Company is now conducting market research, has shown interest in acquiring the hosting rights for the app, and is currently developing a professional version based on the VP-5 prototype.

Another of our most promising innovation programs appeared to be headed toward realization before being dismissed due to concerns about running afoul of the Program Management Aviation (PMA) office. The plan was to implement an Electronic Flight Bag (EFB) to replace the existing system of paper flight publications. This innovation would use tablet computers and digital flight publication subscriptions to save each squadron approximately $17,000 annually. PMA is currently developing a parallel program, but the estimated fleet delivery date was still at least a year away at the time our project was initiated. Our program would be able to deliver tablets within months. Every detail of the program had been meticulously researched, and drew heavily upon long established, similar programs used by the airlines.

The EFB program was widely supported among VP-5 junior officers, Fleet Replacement Squadron instructors, our own CO and XO, reserve unit squadrons manned by commercial airline pilots, and even had the interest of Commander, Patrol and Reconnaissance Group (CPRG). Unfortunately, information security concerns rooted in a risk averse culture combined with the lack of official approval from higher authorities halted the project prior to purchase. Even though our organic EFB proposal was not accepted, our efforts to address the issue sparked broader interest and pressured PMA to move up its timeline. It is a testament to the power of this innovation process that it could conceive and develop a product that rivaled a parallel effort of the standard acquisition pipeline and a regular program office. Tablets are now forecast to be delivered to the fleet by the end of this year.

Other achievements include a redesign of the Petty Officer Indoctrination course, a Command Volunteer Service Day suggested, planned, and led by an E-3, and an “Aircrew Olympics” which pitted two combat aircrews against each other in a variety of mission-related tasks. These ideas were all generated and executed from within the junior enlisted ranks.

Conclusion

We do not intend to suggest that a smartphone application or volunteer service holds the key to dismantling Kim Jong-Un’s nuclear program or China’s grip on the South China Sea. What we are trying to do is develop a framework in which creative solutions can be cultivated. Not every idea is going to be a grand slam, but before you can hit a grand slam you have to get people on base. The most important point we’ve learned is that the ideas are out there, we can cultivate them, and we’ve so far proven that we have “defense entrepreneurs” that can see these innovative ideas through from the white boards to implementation.

Formalizing an innovation process within a squadron is a new way of doing things and this new approach has been met with a variety of challenges. From stubborn, bureaucratic restrictions to “innovation stagnation,” the innovation construct at VP-5 has faced hurdles along the way and been forced to adapt. In the next installment of this series, we will explore some of these obstacles and describe the ways in which the Innovation Department has evolved as a result.

Lieutenant Ken Flannery is a P-8A Poseidon Instructor Tactical Coordinator at Patrol Squadron FIVE (VP-5). He may be contacted at kenneth.flannery@navy.mil.

Lieutenant Commander Jared Wilhelm is the Operations Officer at Unmanned Patrol Squadron One Nine (VUP-19), a P-3C Orion Instructor Pilot and a 2014 Department of Defense Olmsted Scholar. Hey may be contacted at jaredwilhelm@gmail.com.

Featured Image: A P-8 assigned to VP-5 (U.S. Navy photo)