Any final predictions?

This is the ninth and final regular post in our Maritime Futures Project. For more information on the contributors, click here. Note: The opinions and views expressed in these posts are those of the authors alone and are presented in their personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of their parent institution U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Navy, any other agency, or any other foreign government.

LT Drew Hamblen, USN:

Navy’s experiments with biofuels will fizzle out as an abundance of natural gas and crude oil prices it out of the market.

Felix Seidler, seidlers-sicherheitspolitik.net, Germany:

The international maritime security debate is dominated by U.S. future capabilities, European decline, and the Asian arms race – in particular China. Yet beyond that Brazil will be an interesting player. The country seems to pursue an ambitious fleet-building agenda. Moreover, Brazil trained China’s carrier pilots. With a mid- to long-term perspective, a Brazilian blue-water navy might go on expeditionary tours – not to win wars per se, but to take part in international operations or underline Brazil’s new geopolitical status. Why shouldn’t Brazilian and Chinese carriers visit each other’s countries to deepen political ties between both governments?

Bryan McGrath, Director, Delex Consulting, Studies and Analysis:

Most of my predictions will be wrong.

Sebastian Bruns, Fellow, Institute for Security, University of Kiel, Germany:

“A ship in port is safe, but that is not what ships are built for”

– Attributed to Benazir Bhutto

CDR Chuck Hill, USCG (Ret.):

In the most likely conflicts, large numbers of vessels will be needed to perform blockade and marine policing to prevent use of the use of the seas for transport of weapons, supplies, and personnel. We will never have “enough.” The U.S. Coast Guard will be needed to supply some of them.

Biometrics, the ability to positively identify individuals, is already in use in counter-piracy operations and may become important in tracking down terrorists and agents in unconventional asymmetric conflicts.

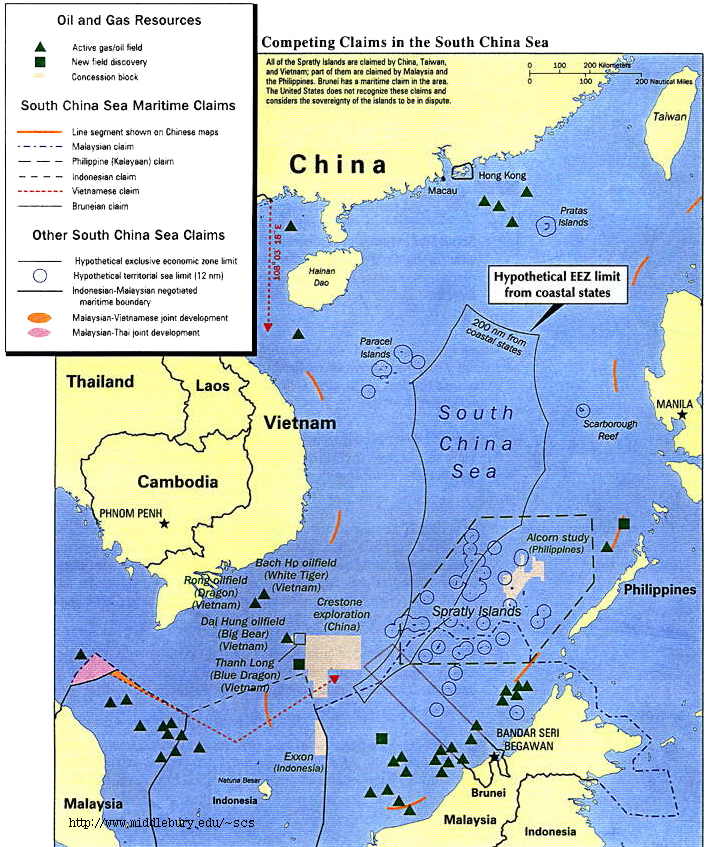

States led by China will attempt to reinterpret the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to apply the restrictions and requirements of Innocent Passage to the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) as well as the Territorial Sea. Most important is Article 58 Section 3 of UNCLOS: “In exercising their rights and performing their duties under this Convention in the EEZ, States shall have due regard to the rights and duties of the coastal State and shall comply with the laws and regulations adopted by the coastal State in accordance with the provisions of this Convention and other rules of international law in so far as they are not incompatible with this Part.” China will interpret this to mean that anything other than expeditious transit including “spying,” “hovering,” flight ops, and submerged operations might be considered illegal.

LCDR Mark Munson, USN:

The notion of an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) is not new (the formal definition of it extending out 200 nautical miles dates to the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), but it seems to increasingly be at the heart of the various maritime disputes. China’s differences with its neighbors in the South and East China Seas revolve around the desire to secure control of underwater resources by maximizing its EEZ. In addition, China has advocated a state’s right to control or regulate the military activities of other states occurring in its EEZ. If accepted by the rest of the world (which most countries currently do not), such a notion would significantly impact the ability of states like the U.S. to operate forward at sea like it traditionally has. In addition, it is the realization of the negative impacts of a state’s inability to enforce activity in its EEZ (such as piracy in Somalia, maritime banditry and oil theft in the Gulf of Guinea) that has led many states to realize that capable maritime security forces are important, although they may not be able to afford them.

YN2(SW) Michael George, USN:

The U.S. Navy is a vital force in our nation’s defense and will continue to be vital to providing secure waterways around the world. But the fact that it is a national navy and not an international one will cause leaders in other countries to make greater efforts to become more self-reliant.

LT Jake Bebber, USN:

Few in the U.S. want war with China, and few in China want war with the U.S. That being said, the wisdom of the ancients suggests that we are on a collision course. 2,500 years ago, Thucydides wrote “The growth of the power of Athens, and the alarm which this inspired in Lacedaemon, made war inevitable.” Fear, power and interest, often involving third parties (see Corcyra in 440 B.C. or Japan today), drive nations to war, and human behavior remains largely unchanged over the last 5,000 years of recorded history, despite our fallacious belief in “progress.” War will come when it is most inconvenient, unexpected, dangerous, and costly – not when we are prepared.

LT Alan Tweedie, USNR:

DDG 1000 will cost even more than we expect and none of the three we are building will ever see 20 years of service life. Neither this ship nor anything else like it will be a part of our Navy’s future.

LT Scott Cheney-Peters, USNR:

These are a little further out in left field, and focus a bit more on geopolitics than the predictions made to earlier questions, so I fully expect them to make me look a bit ridiculous in the years ahead:

While much has been written about Brazil’s burgeoning economic power – slowing of late – and the nation’s drive to reinvigorate its naval capabilities, it will be Columbia and Mexico that surprise the Western Hemisphere’s observers with their growing naval clout. The focus of these nations’ fleets will also shift from the traditional hemispheric concerns to protecting trade ties to Africa and Asia. This is of course predicated on both countries’ ability to keep a lid on domestic discontent and violence while extending their economic booms. Other South American armadas – such as those of Peru, Uruguay, and Chile – will endeavor to maintain their small but professional capabilities, and undertake a similar drive (underway in many cases) to boost ties across the Pacific and Atlantic.

The leaders of both Cuba and Venezuela have not long to live, yet neither change at the top will mean much in terms of naval policy. Both nations may seek to defrost relations with the U.S. and strengthen integration in cooperative regional maritime efforts – although again, little change from now.

The professionalization of Africa’s maritime forces will continue apace in those nations enjoying peaceful transitions of government. Cooperative regional efforts will combat the threats of piracy, maritime robberies, and drug-running – but the dangers will continue at modest levels and readily flourish in any coastal power vacuum. Counter-drug ops will prove the hardest to due to pervasive levels of corruption in states such as Guinea-Bissau.

The Persian/Arabian Gulf will remain a tinderbox – not due to a looming confrontation with Iran, but because the Arab Spring has yet to fully play out on (or off the coast of) the Arabian Peninsula. I don’t presume to know the outcome or timeline, but escalating repression of the Shia majority in Bahrain could lead to untenable situation for the U.S. Fifth Fleet HQ, and/or a change of government.

Lastly, in Asia, the oft-overlooked Indonesia has the potential to develop into a naval power in its own right. The nation’s leadership has aspirations of becoming a key player in South Asia, and it will likely attempt to play the role of a non-aligned honest broker in any regional stand-off. If you’re looking for good coverage of Indonesia (and its ties with Australia), check out the sites Security Scholar and ASPI.

Of course, we could always just end up with this:

Simon Williams, U.K.:

Something this writer believes policy makers and the military should be mindful of in the coming decades will be the increasing significance of the maritime realm in dictating the machinations and dynamic of international relations. Not only are burgeoning economic powers in the Far East developing credible naval forces to guard their interests, but, having suffered a bloody nose in a protracted counter-insurgency campaign in Afghanistan, Britain and the United States will find it difficult to conjure up the public support for any ground operations in the near future.

LCDR Joe Baggett, USN:

No predictions – Just observations:

– In my opinion, the United States and its partners find themselves competing for global influence in an era in which they are unlikely to be fully at war or fully at peace.

– The security, prosperity, and vital interests of the United States are increasingly coupled to those of other nations.

– We must be as equally committed to preventing wars as we are to winning them.

– As ADM Locklear once said “I value surface forces that are:

1) Sufficient in number: you have to be there in order to make a difference

2) Capable, both offensively and defensively: our lethality must be compelling, and our presence re-assuring to our allies

3) Ready, both in proficiency to the full range of potential missions and in proximity to where they’re needed

4) Relevant: the right mix of the above factors to achieve the broad missions sets assigned.”