By Joshua Tallis

Terrorist.

Few words evoke such an instant impression of pure evil. Somehow criminal, fanatic, extremist, none of these are adequate to describe the depravity of terror.

Terrorism.

Few words produce such a sense of dread in the pit of your stomach.

Yet, for a word with so much power, it is also incredibly contentious.

On September 11, 2012, armed men descended on the United States’ consulate in Benghazi, Libya. Ambassador Christopher Stevens and Foreign Service Officer Sean Smith were both killed in the attack. And for the last three years, the media and Washington have been in a never-ending debate over one question: was this, or was this not, an act of terror?

What was the source of this confusion? And moreover, why does it matter?

It matters because terrorism is a special word. Those emotions you feel when I write ‘terrorist,’ or when pundits speculate whether a shooting or a missing airliner was the product of terrorism, makes for a word with significant baggage.

This baggage is powerful in the political arena. It means that politicians can access deep emotions with relatively simple rhetoric.

But this baggage wreaks havoc in the academic sphere. Georgetown’s Bruce Hoffman writes that terrorism is a uniquely pejorative word, which means our use of it in scholarship is laced with normative assumptions. In other words, bias. Terrorism is universally recognized as a bad word; no one wants to be called a terrorist. Our use of the term means we are making a moral judgment about the people involved, about their cause.

We are accustomed to using terrorism predominantly as a political weapon. I call someone a terrorist because I disagree with them— vehemently. And because of the baggage this word carries, I gain the moral high ground if I can convince others to call them a terrorist as well.

And much of this isn’t wrong. Terrorism is undoubtedly a pejorative word, and using it does rightfully impart a sense of morality. But simply leaving terrorism defined as something so obscure is not too helpful, most of all because it leaves the idea of terror so nebulous that it appears up for debate.

We’ve all heard the phrase, ‘one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.’

I may disagree with this sentiment, and indeed I do, but when we limit our understanding of terrorism to its barest, good guy versus bad guy narrative, we invite a relativistic debate where there shouldn’t be one.

And in our daily lives, this is the definition of terrorism we most commonly encounter and employ. As Hoffman writes:

“Pick up a newspaper or turn on the television and—even within the same broadcast or on the same page—one can find such disparate acts as the bombing of a building, the assassination of a head of state, the massacre of civilians by a military unit, the poisoning of produce on supermarket shelves, or the deliberate contamination of over-the-counter medication in a drugstore, all described as incidents of terrorism. Indeed, virtually any especially abhorrent act of violence perceived as directed against society—whether it involves the activities of antigovernment dissidents or governments themselves, organized-crime syndicates, common criminals, rioting mobs, people engaged in militant protest, individual psychotics, or lone extortionists—is often labeled ‘terrorism.’” (Inside Terrorism 2006)

Clearly, we need to get a little more specific. So, where does anyone start when they need to look up a definition? If I’m being honest the answer is Google, but for dramatic effect let’s say the dictionary.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines terrorism as follows:

“Terrorism: A system of terror. 1. Government by intimidation as directed and carried out by the party in power in France during the revolution of 1789–94; the system of “Terror.” 2. gen. A policy intended to strike with terror those against whom it is adopted; the employment of methods of intimidation; the fact of terrorizing or condition of being terrorized.” (Inside Terrorism 2006)

What would that mean in practice? Well, let’s see.

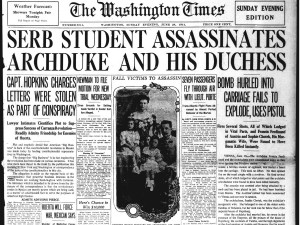

On June 28, 1914, Austria’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife were shot and killed while visiting Sarajevo. Gavrilo Princip, their assailant, has been widely regarded as a terrorist for his role in precipitating the start of the First World War. But was this really an act of terrorism? Well, it doesn’t have much to do with the French revolution, but I think it’s fair to say this murder produced widespread terror. So by the dictionary definition of terrorism, I’d have to say the death of the Archduke fits the bill.

But somehow this leaves me unfulfilled. “A system of terror—” that’s pretty vague. The reference to eighteenth century France is historically accurate, but also not very helpful. And “the fact of terrorizing or condition of being terrorized” is like defining hunger as the act of being hungry—it doesn’t give us much new information. We need more.

In a seminar on terrorism I attended in 2014 organized by the European International Studies Association and Yale University, Tamar Meisels from Tel-Aviv University advanced a definition of terrorism I found particularly compelling. To Tamar, Terrorism is “the intentional random murder of defenseless non-combatants, with the intent of instilling fear of mortal danger amidst a civilian population as a strategy designed to advance political ends.” (http://www.ucl.ac.uk/~uctytho/MeiselsTheTroubleWithTerror.html)

Tamar is guided by Michael Walzer, whose 1977 book, Just and Unjust Wars, helped disentangle terrorism from other forms of revolutionary violence. Revolutionary violence, by its very nature, implies that the actors undertaking it are not state-actors, and seek to radically alter the status quo. Walzer divides such violence into three categories.

The first is guerilla warfare. Guerillas typically launch attacks against an opposing military, limiting strikes against civilians. With victory, guerilla tactics are often easily justified, especially if the cause is deemed moral, like national self-determination or anti-colonialism.

Walzer’s second category is political assassination. Assassinations are targeted, demonstrating some distinction between valid and invalid targets, however unseemly. The violence is not random.

What is left is terrorism, which by process of elimination must target innocent individuals randomly in the pursuit of some political agenda.

To make things even clearer, we can disassemble the principles of this definition into five characteristics:

- Violence—Terrorism necessarily includes the use or threat of violence directed against a population.

- Motivation—Terrorism is used to achieve a political objective. By political, we mean that terrorism is intended to produce some sort of change in the political regime, however unlikely that may be.

- Victim—There is a lot of debate over who constitutes a victim of a terrorist attack. Here, victims are randomly targeted civilians, not directly related to a cause and unable to defend themselves.

- Audience—Terrorism, without an audience, is just a crime. Terrorism is propaganda by the deed, and thus it must be witnessed. This is because, while the victims of an attack may be terrorized, they are not the intended audience. To achieve a political objective, terrorism must induce a government or powerbrokers to choose a certain course of action in line with the terrorist’s objectives.

- Actor—Groups without the right to legitimately use violence. In traditional political science, we define state sovereignty as the monopoly over the legitimate use of force, according to sociologist Max Weber. In other words, only states hold the right to exercise violence lawfully in conventional political philosophy. Under this rubric, terrorism cannot be practiced by states. Now, as I’ve noted, terrorism is a contentious topic in academia, and among the hundreds of definitions of terror, there are those that would include notions of state terror, which is itself a robust area of study. Entertaining both modes of violence in the same category, however, widens the use of the word terrorism so much as to almost become cumbersome. In the interest of balancing simplicity with clarity, I prefer to keep state terror and non-state terrorism in two separate bins.

So, what does this mean in the real world?

Let’s apply these five principles—violence, motivation, victim, audience, and actor—to some examples and see what happens.

And let’s start with the murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

Number one, the use of violence, is clearly fulfilled.

Princip also fits the bill for number five, the actor. As an affiliate of the Black Hand, a militant nationalist organization, Princip was acting without legal authority to employ violence.

The incident also clearly fits number two, motivation. As a movement for self-determination, the Black Hand included many Yugoslav nationalists. And it was this broad aim that brought Princip to violence.

Number four, the audience, also seems to fit. Nineteenth and early-twentieth century terrorists, mostly anarchists, popularized ‘the propaganda of the deed,’ the idea that dramatic incidents were necessary for spreading revolution. In this regard, any public act of political violence speaks to an audience and fulfills that criterion. More specifically, the death of the heir apparent of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was clearly designed to send a message about the consequences of their continued presence in the Balkans.

Yet, the killing of Archduke Franz Ferdinand fails to meet the benchmark for the third characteristic, the victim. Applying Walzer’s categories of revolutionary violence, Gavrilo Princip was an assassin, not a terrorist. His victim was not random or unrelated to the success of Princip’s cause. None of this is to validate Princip’s actions, neither is it to say that his actions did not stir considerable terror. But according to this conception of terrorism, the assassination of the Archduke doesn’t pass muster.

How about another case, during the Lebanese Civil War?

On October 23, 1983, 299 American and French soldiers were tragically killed when two truck bombs detonated at the U.S. barracks in Beirut. The death toll marked one of the deadliest attacks on American soldiers since World War II. The Islamic Jihad Organization took credit for the devastation, which eventually precipitate an American withdrawal from Lebanon in 1984. It is frequently regarded as one of the most significant acts of terror in the last half-century.

Is it?

As with our first case, this clearly fits the criterion for violence

This attack also fits number two, motivation. Islamic Jihad was a Shiite militia whose aim was the withdrawal of Western forces from Lebanon, a political objective.

Number four, audience, is also apparent. The soldiers targeted may have been the victims, but the message was certainly intended for Washington.

Things get a little murky with respect to the perpetrator. Iran’s fingerprints were all over this attack, and they likely provided some intelligence, training and resources to make it happen. Still, Islamic Jihad, a non-state actor, was the group that eventually carried out the bombing, so it is fair to say the attack fits this category despite a relationship with state-sponsorship.

As with the assassination of the Archduke, however, this attack also fails to meet the characteristic for victims laid out above. As soldiers stationed in a conflict zone, Marines do not fit the status of randomly targeted civilians. Again, this is emphatically not an excuse for the attack, but it is illustrative of how important it is to find more enhanced words to frame such non-state violence.

This case is particularly demonstrative, as a renowned terrorism scholar relayed to me. The scholar noted that our field is riddled not only with conflicting definitions of terrorism, but also inconsistencies within individual works. An author may define terrorism on page 10 of a book as I did above, but by page 50 he or she is already referring to the Barracks Bombing as an act of terror, even though it fails to meet all markers. Scholars of terrorism are just as susceptible to the baggage associated with the word as anyone else, and often times we fail to remain consistent in our own applications of the terminology.

You’ll probably find that, at least in some instances, this academic understanding of terrorism may not align perfectly with events we instinctively regard as such. I would consider that a good thing, cause for coming up with better terms for acts of political violence. But some may find that overly restrictive, and you wouldn’t be alone. There are myriad definitions out there. Find one that makes sense to you. What matters most is that you are consistent in your application of the definition. Without a shared understanding of what terrorism means, we cannot ensure we are all speaking the same language.

So, was the attack on the U.S. Consulate in Benghazi an act of terror? You tell me.

Joshua Tallis is a PhD candidate at the University of St Andrews’ Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence. He is a Research Specialist at CNA Corporation, a nonprofit research and analysis organization located in Arlington, VA. The views and opinions in this article are his own and do not necessarily represent the position of the University or CNA.