Recent Chinese pronouncements regarding the shift of their Navy from defensive to potential offensive operations contain a refrain with which naval historians are most familiar. It is a song once sung by another continental military power newly flush with a successful and expanding international economy.

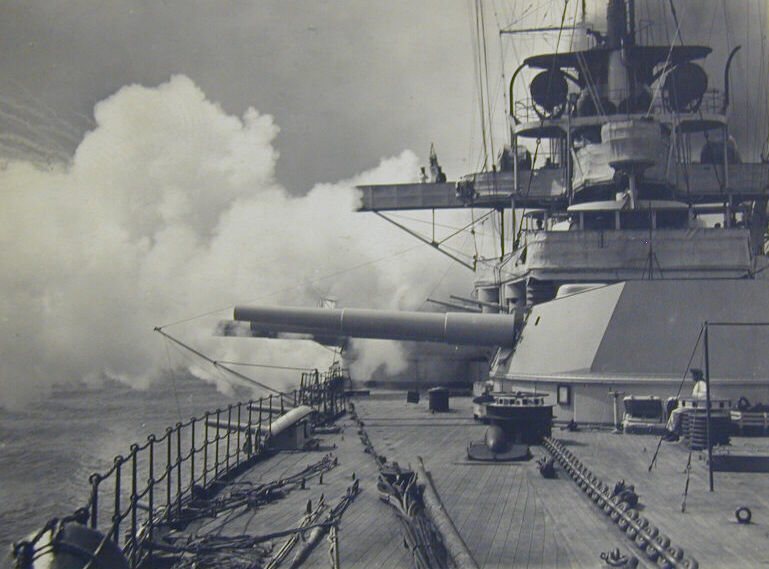

China’s shift toward an offensive naval capability sounds very similar to the formation of the Imperial German High Seas Fleet (Hochseeflotte) in 1907. The Chinese and Hohenzollern navies have many commonalities in origin, training and choice of force structure. Their strategy, operational art and tactics are also remarkably similar to Kaiser Wilhelm’s fleet of the late 19th and early 20th century. The Chinese Navy may have also replicated the fatal flaw that left the High Seas Fleet incapable of achieving the victory it came so close to achieving in late 1917. Like the German imperial elite of the late 19th century, the Chinese Communist Party is now also seeking “a place in the sun” through President Hu Jinatao’s “new historic missions” assignment of 2004. China may too think that “its future is on the water” as did the Kaiser’s navy over a century ago. Such visions, however, for a fleet that has not seen battle against a peer opponent since 1894, can be dangerous.

Similar National Origins and Early Dismal Performance

Like Imperial Germany, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is a continental land power that must look far into its past to find naval virtue. The Kaiser had to search back to the fifteenth century Hanseatic League in order to find heroic German maritime exploits that might be emulated by his own 20th century sailors. The PRC must equally rely on the historically remote Islamic Admiral Zheng He, who served the Ming Dynasty Yongle Emperor in the early 15th century as both a land and ocean-going commander. Both fleets were traditionally led by army officers and designed for coastal or at best littoral operations.

Both the German and Chinese fleets suffered from timid national leadership, and a paucity of training and operations that led to enforced idleness or defeat as late as the 19th century. Other Baltic powers often made short work of the Prussian Navy in war. The Swedes completely annihilated a Prussian fleet at the Battle of Frisches Haff in 1759. The Prussian Navy played practically no role in the three 19th century conflicts precipitated by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck that led to German unification. Its Danish, Austrian and French opponents either ignored, blockaded, or chased the small Prussian Navy from the seas. The Imperial Chinese Navy also suffered from neglect and poor performance from the Early Modern Period into the 20th century. The forces of the East India Company and the British Empire made short work of primitive Chinese warships in the two Opium wars of the mid 19th century. The French Navy destroyed the Chinese Fujian Fleet at the Battle of Fuzhou in 1884 and the Imperial Japanese Navy decisively defeated the Chinese Beiyang Fleet at the Battle of the Yalu River in 1894. The post-1949 People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has fought minor skirmishes against the Vietnamese, but has yet to engage anything approaching a regional, nor peer opponent in naval combat.

The German High Seas Fleet and the PLAN both had to be “reborn” in new political and economic environments of their respective nations. The united German state surged to new economic power between 1871 and 1906 and surpassed the British in steel production halfway into the first decade of the 20th century.[1] Germany also came close to equally British world trade and coal production by 1914.[2] Great Britain continued to prosper as both Germany and the United States surpassed Britain in key economic indicators and Britain’s Gross National Product grew from 1.32 billion to 2.1 billion Pounds over the period from 1870-1900.[3] Despite these changes, the British Empire did not regard either Germany of the U.S. as a potential enemy, and Canada’s shared border with the U.S. caused more concern to the British in 1900 than did Germany’s economic growth.[4] Germany, however, despite its unchallenged economic success decided to engage the British Empire in a naval building race that the British did nothing to instigate. Some historians have said the British detainment of several German ships transporting relief supplies to Dutch Boers during the Second Boer War (1899-1902), served as a catalyst for the passage of the German Second Naval Law which was much more provocative and aimed at Great Britain than its predecessor.[5] Emboldened by economic success and military strength, and baited into action by its inability to influence sea lines of communication outside its sphere of influence, Germany embarked on a risky warship building competition with the established naval hegemon at the time and made that challenge right on that naval power’s home doorstep.

China has had an equally meteoric economic rise since the time it also changed political organization by throwing off its Maoist past and embracing state-sponsored capitalism. Like Imperial Germany, post Mao China has combined pride in economic growth with its aggressive continental past. The People’s Republic appears to have had the same sort of decisive “maritime moment” as Imperial Germany when the U.S. deployed two aircraft carriers to the Taiwan Strait in 1996 as a response to simmering tensions between the PRC and Taiwan. There appears to have been a similar rage amongst the Chinese Communist Party and military leadership over the 1996 US deployment, as there was from German Aristocrats, businessmen and military leaders over the seizure of German relief ships off South Africa in 1900. It is this kind of significant public support that allowed for the growth in the German Navy of the early 20th century and may play a role in public support for an expanded PLAN.

Both fleets also began as coast defense organizations led by Army officers and dependent on inexpensive denial capabilities. The early German Imperial Navy was first led by infantry General Albrecht von Stosch and General (and later Imperial Chancellor) Leo von Caprivi. It had few large ships and invested much of its effort in the development of torpedo craft and mine warfare. The architect of the High Seas battlefleet, Admiral von Tirpitz, and many of the Imperial Navy’s future senior officers came out of the German Navy’s torpedo boat arm. While Kaiser Wilhelm II played a very public advocacy role for larger and more capable surface ships, such expansion would not have been possible in the absence of strong support from the German business and political community. While perhaps not fervent navalists like the Kaiser, they certainly thought that having a Navy to protect emerging commercial interests was a good investment, and were willing to invest in Germany’s new naval effort. The spirit of American navalist Alfred Thayer Mahan’s writings on the importance of a battle fleet to a nation’s political and global economic health found as many adherents in Germany as it did in Great Britain, the United States, and Japan.

The early PLAN was also led by Army Generals. The most prominent advocate of improving Chinese naval capabilities was General Liu Huaqing, who served as PLAN commander from 1982-1987.[6] China’s naval strategy from 1949 through the 1980’s was also remarkably similar to Germany’s in that it was focused on coastal defense and emphasized missiles, torpedoes and mines deployed from small, coastal combatants. China appears to have also embraced the theories of Alfred Thayer Mahan as Germany did a century ago and added the study of the American navalist’s works to the curriculum of its advanced naval education courses.[7]

Part two of this article will examine how Hohenzollern Germany and the People’s Republic of China developed striking similarities in force structure, naval strategy, and deployment of their naval forces.

Read Part Two here.

Steve Wills is a retired surface warfare officer and a PhD candidate in military history at Ohio University. His focus areas are modern U.S. naval and military reorganization efforts and British naval strategy and policy from 1889-1941.

[1] Aaron Friedberg, The Weary Titan; Britain and the Experience of Relative Decline, 1895-1905, Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1988, p. 25.

[2] Ibid, pp. 24-25.

[3] Ibid, p. 24.

[4] Ibid, pp 185-186.

[5] Keith Wilson, editor, The International Impact of the Boer War, Abingdon Oxon, UK, Routledge, 2014, pp. 36-38.

[6] https://cimsec.org/father-modern-chinese-navy-liu-huaqing/13291, last assessed 16 June 2015.

[7] Howard J. Dooley, “The Great Leap Outward: China’s Maritime Renaissance”, The Journal of East Asian Affairs, 01 March 2012, p. 69.