By Dr. Ian Ralby, Dr. David Soud, and Rohini Ralby

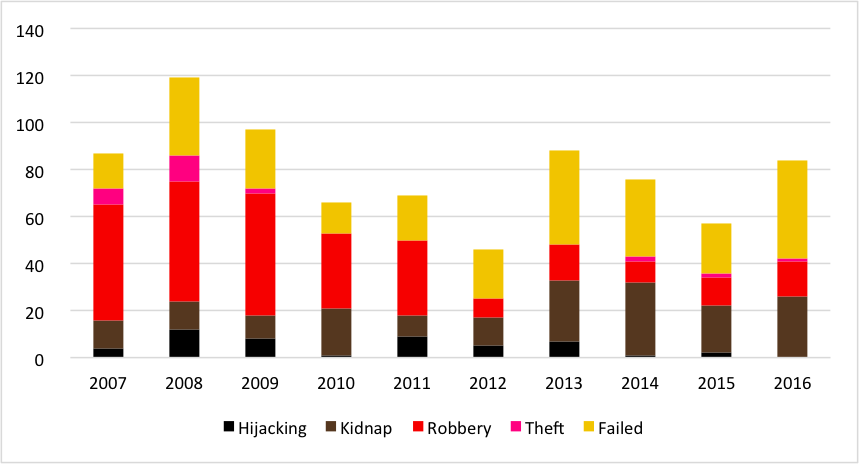

Few regions of the world have seen more improvement in maritime security institutions over the last five years than the Gulf of Guinea. At the same time, however, maritime security threats across West and Central Africa have continued to evolve and are increasingly difficult to address. Ironically, the region is becoming a victim of its own success: improved maritime law enforcement drove criminals to become both more brazen and more innovative in how they pursue illicit profit. These heightened challenges, however, are no longer as insurmountable as even basic ones were a decade ago. Having built one of the most sophisticated and promising sets of maritime security architecture in the world, the Gulf of Guinea is actually well-placed to take on the new challenges it faces.

To maximize the efficiency and effectiveness of this architecture in confronting these threats, a new element has to enter the conversation: technology. States, zones, regions, and the wider interregional mechanisms must all explore ways of leveraging technology to realize their respective mandates in the most cost effective way. Five years ago, discussing maritime technology would have been of limited value, as the state and cooperative mechanisms across West and Central Africa were too nascent to take advantage of it. Now, however, the Gulf of Guinea is primed to make better use of maritime security technology.

The Gulf of Guinea Has Momentum

While progress in developing functional maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea may not have been as fast as some would prefer, it is now moving rapidly, and its trajectory is unmistakable. The signing of the 2013 Code of Conduct Concerning the Repression of Piracy, Armed Robbery against Ships, and Illicit Maritime Activity in West and Central Africa – known informally as the Yaoundé Code of Conduct – catalyzed an intensive process of national, zonal, regional, and interregional improvement that continues to gain momentum. As Article 2 of the Code states, “the Signatories intend to co-operate to the fullest possible extent in the repression of transnational organized crime in the maritime domain, maritime terrorism, IUU fishing, and other illegal activities at sea.” This initiative has given rise to a multi-tiered effort.

At the national level, states are working to establish interagency processes for maritime governance, and to develop and implement national maritime strategies. States will remain the fundamental building blocks of maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea. Only through the national laws of the regional states can maritime crimes be effectively prosecuted. Beyond these national efforts, however, the states are engaging in an increasingly integrated, multilateral architecture that facilitates seamless cooperation.

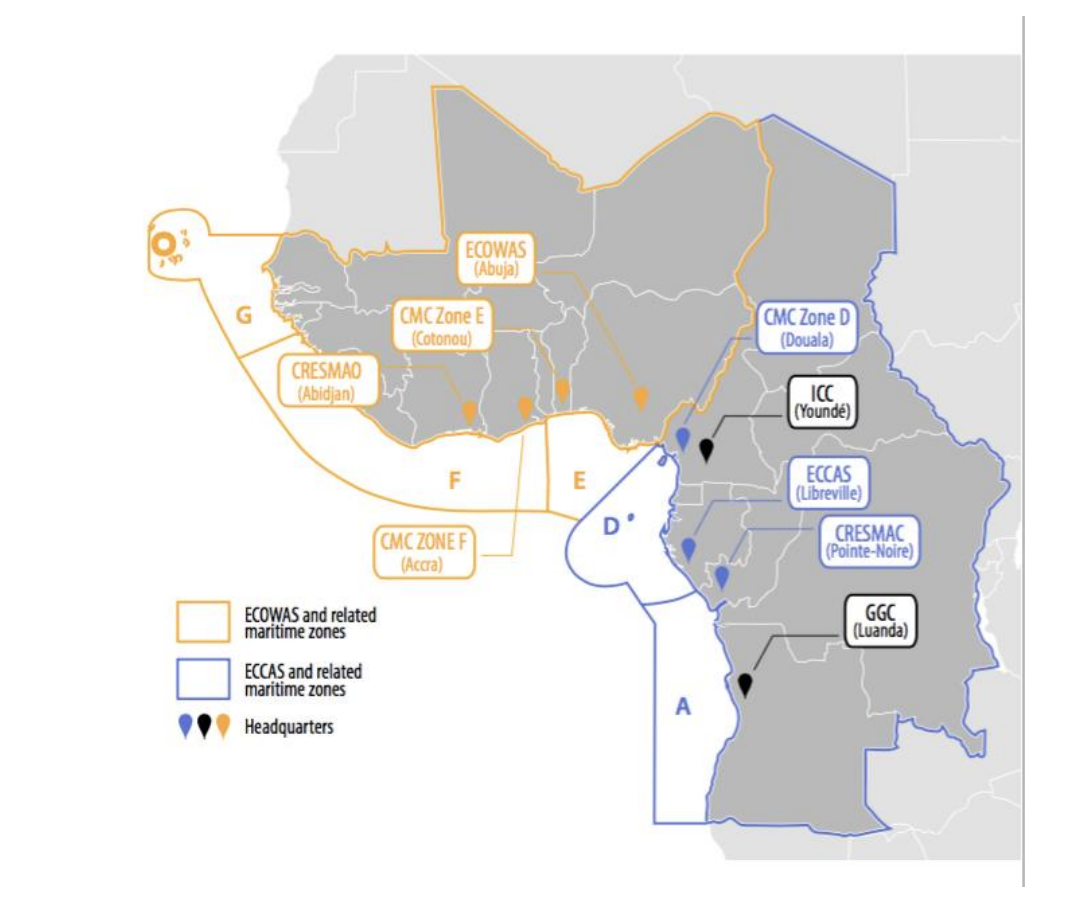

The states, including the landlocked signatories to the Yaoundé Code of Conduct, are grouped by their respective Regional Economic Communities (REC) into maritime Zones. The Economic Community for Central African States (ECCAS) has Zones A and D (there is neither a B nor a C) and the Economic Community for Western African States (ECOWAS) has Zones E, F, and G. The national groupings are as follows, with an asterisk indicating each country that hosts a Zonal Multinational Coordination Center (MCC):

- Zone A: Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo, Congo

- Zone D: Cameroon*, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, São Tomé and Príncipe

- Zone E: Nigeria, Benin*, Togo, Niger

- Zone F: Ghana*, Côte d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea

- Zone G: Cabo Verde*, Senegal, the Gambia, Guinea Bissau, Mali

Each REC also has a corresponding Regional Coordination Center – CRESMAC for ECCAS based in Pointe Noir, Congo, and CRESMAO for ECOWAS based in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. The two regional centers interact and share information with the MCCs to ensure operational cooperation across their respective areas of responsibility.

At the apex of the architecture is the Inter-regional Coordination Center (CIC) in Yaoundé – the intersection of the operational, strategic, and political aspects of maritime safety and security in the Gulf of Guinea. CIC both coordinates and supports the work of the two regional centers, the five zones, and the 25 member states. At the same time, it has the important role of engaging both with international partners and national governments to build political will and ensure the Gulf of Guinea’s momentum continues.

Importantly, the Yaoundé Architecture for Maritime Safety and Security (YAMSS), as the institutional framework is often called, is not merely a nice idea on paper; it is increasingly producing real results on the water. Furthermore, the community of maritime professionals involved in implementing this architectural design are increasingly connected with each other and working collectively to make maritime safety and security a reality in the Gulf of Guinea. As perhaps the most notable example, Zone D already serves as a leading example of how to conduct systematic combined operations at sea for maritime security, not just in Africa but around the world. CRESMAC and CRESMAO are becoming increasingly operational in sharing information across their regions and with each other. And CIC is beginning to garner the attention needed to be successful. At every level, there are encouraging signs of growing momentum and increased community among the maritime professionals in West and Central Africa.

Most technology for maritime law enforcement is procured at the national level. Given the extent of the integration within the Yaoundé architecture, however, there is also an opportunity for technology to be procured at the zonal, regional or inter-regional levels to ensure harmonization, to streamline access to common, inherently interoperable systems and provide a uniform operating picture.

Technology, some procured within the Gulf of Guinea and some provided by international partners, has been a part of this process from the start. Most of it has involved enhancing visibility to improve maritime domain awareness (MDA). But with the growing coordination across states and regions, and the problem-solving and advance thinking that expansion has generated, key stakeholders have crossed a threshold: they can now discern with confidence what technologies will actually help maximize the impact of maritime operations. The lessons learned along the way merit careful attention from anyone seeking to leverage technology for improved maritime security. What follows are some of those insights.1

Avoiding Information Overload

Improving MDA has been a major focus for years in Africa. But there is a balance to strike: being aware of everything is almost as challenging as being aware of nothing. Efficiency and effectiveness therefore begin with how information is selected and packaged for use on and off the water. Operators from across different maritime agencies share a keen interest in technology that highlights useful, actionable information, and not only collects but also filters input, helping them focus on key areas of concern rather than providing blanket visibility of all maritime activity. Given the region’s limited human as well as financial resources, such technology could guide them toward confidently engaging in targeted interdiction. This holds true for maritime criminal activity as well as fisheries protection.

But to be used consistently and effectively, the technology must be user-friendly as well. Simplicity is an important differentiator between technology that would improve general maritime domain awareness and technology that would actually help operations in law enforcement, fisheries protection, or search and rescue. For instance, artificial intelligence has now made it possible to have an MDA platform that not only shows ship positions and makes recent AIS anomalies visible, but also aggregates a wide range of real-time and historic data and filters them according to selected parameters, providing instant alerts to suspected illegal activity. That array of functions would allow for both launching decisive interdictions and detecting patterns of illicit activity.

Technology Can Facilitate Inter-Regional Harmonization

When any one state or even zone is perceived to be weaker than its neighbors, in terms of either its laws or its capacity for law enforcement, that state or zone becomes a magnet for criminality. Consequently, a major focus of the YAMSS is on harmonization to ensure consistency in deterring and addressing maritime crime throughout the Gulf of Guinea. Depending on how it is chosen, distributed and applied, technology could either exacerbate the problem or help resolve it.

When one state has a significant technological advantage over its neighbors, the neighboring states are likely to suffer. Conversely, when shared technologies are deployed across neighboring zones and regions, new possibilities arise for communication, coordination, interoperability, and even harmonization of legal and regulatory frameworks. Some technologies, for example, could provide insight across the region as to where IUU fishing and illicit transshipment most frequently occur, or call attention to ships on erratic or otherwise suspicious courses. This could in turn inform legislative or regulatory action as well as operational decision-making at the national or zonal levels to help address maritime problems where they are most acute. Such an approach can therefore help CIC with building the political will to harmonize, as well as help the operators in their planning and execution of law enforcement activities. The more seamlessly technology is deployed across a region, the more difficult it becomes for criminals to find venues for illicit activity. As the name suggests, transnational crime is borderless; a common operating picture across the regions is therefore vital to identifying that illicit activity.

Not only have the maritime institutions evolved in recent years, the available maritime technology has developed greatly. Surveillance systems to identify illicit activity on the water – from illegal fishing to illicit transshipment to trafficking and smuggling – have improved dramatically. Employing this technology means that operators are not merely patrolling on the off chance they encounter illicit activity. The confidence of law enforcement agencies that they will not be wasting fuel and other resources is greatly enhanced by engaging in targeted interdiction of vessels reasonably certain to be committing offenses based on real-time information.

If law enforcement agencies can show that their efficiency is such that they have successful interdictions nearly every time they deploy assets, that success can become contagious. It can help energize the maritime agencies, deter criminal actors, and at the same time build the political will to ensure the longer-term safety and security of the maritime domain. Politicians are persuaded by success, and technology can greatly increase the odds of operational success.

Culprits Do Not Have to be Caught Red-Handed

In addition to facilitating targeted interdiction, advanced surveillance technologies can offer a further benefit. Just as a robber could be arrested at home for a heist caught on closed caption television (CCTV), it is now possible for vessels to be arrested in port for illicit actions committed at sea and recorded using sophisticated maritime surveillance platforms. Though CCTV is not a possibility on the water, other technologies including the use of the vessels’ Automated Information System (AIS), Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), and Electro Optical Imaging (EO) can produce high degrees of certainty regarding illicit activity. While states must ensure that their rules of evidence allow for such electronic and digital data to be used in court, this leveraging of historic surveillance data is another way the technology available today can greatly amplify the impact of limited maritime law enforcement resources.

Technology that helps counter smuggling will inherently benefit two states simultaneously – the state that is losing the smuggled good, and the state that is losing the tax on the importation of that smuggled product. If implemented effectively, technology could disincentivize the smuggling of certain goods. One crucial example of this is fuel: the cost of doing business in illicit fuel could, with effective law enforcement, become higher than that of selling it legally, thereby making it an unattractive business proposition. A suite of technologies such as molecular marking, GPS tracking of shipments, digital documentation, and state-of-the-art metering, strategically implemented across the Gulf of Guinea, would alter the risk-reward calculus and help West and Central Africa eradicate most cross-border smuggling of fuel. These and related technologies could also appreciably mitigate other modalities of illicit trade, including counterfeit tobacco and pharmaceuticals.

Technology that Pays for Itself Sells Itself

For states and multinational bodies working to secure and govern vast maritime spaces that seldom command the political attention they deserve, investments in technology have to bring returns that justify initial and ongoing expenditure. Technologies that enable more streamlined and cost-effective operations, that combat activities that lead to substantial economic losses, or that actively generate revenue in the form of taxes, fees or various kinds of penalties are preferable to those that run at ongoing cost.

Countering IUU fishing, prosecuting environmental crimes, and combating fuel smuggling are three efforts that could hold precisely this kind of appeal. Acquiring new technology that can stem economic losses from depleted fisheries and degraded marine spaces, elicit substantial financial penalties for illegal fishing or environmental, dumping, recover revenues previously lost to fuel smuggling or prevent subsidies fraud may well find more support among decision-makers than procuring more patrol vessels that need to be crewed, fueled, and maintained. And when the technology begins to pay for itself and lead to more success on the water, investing in new patrol vessels that can amplify that success also begins to look more attractive.

If the political classes can see financial return on investment as well as improved maritime safety, security, and sustainability, wider adoption of the technology becomes more likely. Furthermore, if the procurement approach does not put all the economic burden on the purchaser, but rather balances investment and return, the Gulf of Guinea states are more likely to proceed.

Maritime Safety, Security and Resource Protection Can Share Technology

The Gulf of Guinea Code of Conduct not only laid the groundwork for an inter-regional security architecture, it also established IUU fishing as a crime coequal with piracy, trafficking, oil theft, and other illicit activities. This move made it possible to establish far more effective legal deterrents than the administrative penalties that often accompany fisheries-related crimes. It also allows for more sharing of technology and information across agencies that combat the full range of illicit maritime activities. In light of how such criminal enterprises as IUU fishing, trafficking, and oil theft often overlap, sharing technology in this fashion can close gaps in law enforcement that criminals have all too often exploited.

Given that limited resources become even more limited when they are divided among multiple agencies trying to accomplish similar tasks, this sort of integration could have an immediate impact on maritime safety, fisheries protection and maritime security. Such sharing of resources, however, necessitates a functional interagency mechanism for maritime governance. Thus the state-level work on both whole-of-government approaches to maritime security and integrated maritime strategy development and implementation go hand-in-hand with the prospects for effective use of such technology.

Technology Can Both Help and Complicate Legal Finish

One of the most difficult challenges for the Gulf of Guinea, and indeed for any region, is translating operational successes into legal finish. If no prosecutorial or regulatory action is taken to penalize illicit activity, maritime law enforcement becomes a matter of catch and release. Technology can play an important role in assisting with maritime interdiction, but it also has an essential role to play in effectuating legal finish.

That said, a challenge must first be overcome. Not all legal systems have provisions for technological, digital, or electronic evidence. In order to be able to use the evidence provided by the MDA and monitoring, control, and surveillance (MCS) technologies now emerging, the state’s evidentiary rules must be amended to ensure that technology can be used in court. If those evidentiary rules are more permissive, however, there is another possibility for assisting law enforcement.

Traditionally, in the maritime space, perpetrators have to be caught in the act. But, as noted above, technology that provides evidence of illicit activity at sea could potentially be used to arrest vessels at the pier and on their return from a voyage that involved a breach of the law. In other words, limited vessels or a lack of fuel would not be a barrier to arrest and prosecution. Furthermore, regardless of where a vessel was caught, historical data could be used to increase the charges and penalties for prior offenses as indicated by the technology.

Conclusion

The Gulf of Guinea is ready to more effectively use technology to enhance the work done to develop and operationalize the cooperative maritime security architecture in West and Central Africa. Cost-neutral or even revenue generating technology is most likely to garner the necessary political will, but from an operator’s standpoint, simplicity is also key. In addition to aiding targeted interdiction, technology can help provide the evidence for pier-side arrests and even enhance charges and penalties based on prior illicit activity. That said, legal systems must account for such technological evidence in court. Harmonized legal finish across the Gulf of Guinea must be a central focus, as that is the only way to change the risk-reward calculus and ensure that no state or zone becomes a magnet for crime.

In a larger, more strategic sense, the individual states and regional bodies pursuing greater maritime security and development in the Gulf of Guinea must also work together to harmonize their more foundational approaches to the challenges facing the region. Too often stakeholders presented with the chance to cooperate or collaborate in confronting such issues fall into the trap of viewing that effort in terms of false dichotomies. They may rightly be keen to exercise autonomy in light of a history in which their sovereignty has been compromised. But they may also unhelpfully misinterpret the cooperative and collaborative harmonization of approaches as being a threat to sovereignty. In an effort to maintain their autonomy, they may therefore isolate themselves, and consequently become more of a magnet to the highly cooperative, transnational criminals they face.

| Exercising autonomy | Losing sovereignty |

| Isolating | Cooperating and collaborating |

This diagram reveals how the terms of a dichotomy are never simply binary, but actually part of a cluster of related terms that are often conflated, or defined in varying ways.2 Failing to get outside the “box” formed by these choices can narrow vision and obstruct communication, and thus frustrate efforts at progress. The stakeholders in the Gulf of Guinea must clarify for themselves and each other the difference between exercising autonomy and isolating themselves, and between cooperating or collaborating and losing sovereignty. If everyone can achieve this “outside-the-box” clarity, progress can happen quickly and effectively. While many of the maritime operators recognize these nuanced dynamics, they have a challenge to overcome in convincing their political leadership to move past a limiting dichotomy centered on autonomy, and instead embrace cooperation and recognize the value in sharing resources and technology to secure, govern, and develop the maritime space in the Gulf of Guinea.

The work of maritime professionals in West and Central Africa to pursue safety, security, and sustainability in the maritime domain has already led to some notable successes. Now it is in a position to begin realizing the ambitious vision of successfully securing, governing, and developing the region’s maritime domain. This is where new, better, and more effectively used technology can play a pivotal role by enabling individual states and regional bodies to make far more effective use of their resources to control the maritime space. Stakeholders must now select the right tools for the job – those that provide the necessary precision, simplicity of use, cost-effectiveness, and ability to link efforts across both agencies and maritime boundaries.

Ian Ralby is a recognized expert in maritime law and security, serving as Adjunct Professor of Maritime Law and Security at the US Department of Defense’s Africa Center for Strategic Studies; a Maritime Crime Expert for UNODC; and as CEO of I.R. Consilium, a family business that works matters of security, governance and development.

David Soud is Head of Research and Analysis at I.R. Consilium and works on issues at the intersection of fisheries governance and transnational organized crime.

Rohini Ralby is Managing Director of I.R. Consilium and works on strategy development and implementation.

References

1. A recent public-private conference organized by the US firm I.R. Consilium, LLC in Freetown, Sierra Leone explored this topic and served as the basis for the key points of this article.

2. The diagram is an example of the “fourchotomy,” a strategic tool devised by Rohini Ralby.

Featured Image: GULF OF GUINEA (April 2, 2014) A U.S. Coast Guard law enforcement detachment member and a Ghanaian navy sailor inspect a fishing vessel suspected of illegal fishing during the Africa Maritime Law Enforcement Partnership. The partnership is the operational phase of Africa Partnership Station and brings together U.S. Navy, U.S. Coast Guard, and respective Africa partner maritime forces to actively patrol that partner’s territorial waters and economic exclusion zone with the goal of intercepting vessels that may have been involved in illicit activity. (U.S. Navy photo by Kwabena Akuamoah-Boateng/Released)