This is an article in our first “Non Navies” Series.

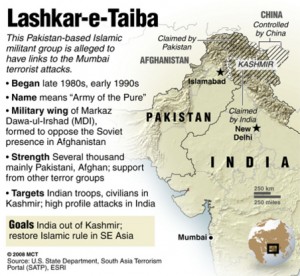

Nearly six years ago, Pakistani terrorists from Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT, meaning Army of the Righteous) launched a sophisticated raid on the Indian port of Mumbai. Ten LeT operatives held the city captive from 26-29 November 2008, killing 164 people and injuring more than 300 others. Fascinating in its counterterrorism aspects, the Mumbai attack is particularly noteworthy for those of us in maritime professions because of how they got there: by sea. LeT highlighted in detail how an irregular organization can circumvent landward control measures by turning to the maritime environment.

Violent extremist organizations (VEOs) such as LeT succeed in irregular warfare by going where government authority is absent or insufficient. The Indo-Pak coast is no exception. The expansive region has supported the livelihood of fishermen and merchants for centuries, making it a permeable environment where minimal government presence was (and remains) tolerant of transient craft. Such an environment offers myriad advantages compared to overland routes where government checkpoints and patrols are far more rigorous. VEOs continue to pursue these overland routes for infiltration or smuggling, but LeT minimized the chance of their high-stakes attack being interdicted by Indian authorities when they chose to come by sea.

The raid itself wasn’t the first iteration of LeT’s maritime infiltration. For example, in late-2006/ early-2007 eight operatives rendezvoused at sea with Indian LeT members aboard an unidentified fishing vessel and returned with them to reconnoiter Mumbai. This gave them ample opportunity to assess the coastal pattern of life, including security presence and traffic density, as well as to gather imagery of everything from landing sites to target location from the perspective of the raiding party. Once ashore they split into two-man teams, just as the raiding party would do, observing the area by travelling from safehouse to safehouse. They were not discovered during the seaborne infiltration nor during the reconnaissance of Mumbai. However, two of the eight were arrested in March 2007 by the Jammu & Kashmir police (Jammu & Kashmir being a state in northern India). During interrogation the two suspects gave specific information about their infiltration of Mumbai as well as LeT’s desire to use the sea as a routine ingress. Neither this shot-across-the-bow nor corroborating intelligence provided by U.S. and Indian agencies proved sufficient to energize India’s maritime security agencies.

After more than a year of training on the Mangla Dam reservoir in Kashmir, the raiding party departed Karachi on 21 November 2008 aboard motor vessel HUSSEINI. They spotted the Indian fishing vessel KUBER two days later in Pakistani waters. Though their plan had been to hijack a Mumbai-based craft in Indian waters, KUBER’s Indian registry enticed them to seize it as an early opportunity. They were able to come alongside, possibly by feigning distress, and quickly commandeeredthe fishing boat. The raiding party embarked KUBER and transferred all of her crew except the master to HUSSEINI. The raiders started towards Mumbai after the equipment was moved aboard and HUSSEINI returned to Karachi. The four fishermen taken from KUBER were executed, their bodies left adrift on the sea.

The transit to Mumbai was filled with map reconnaissance, table-top rehearsals, equipment prep, as well as probable comms checks and intel updates from LeT’s ad hoc operations center in Pakistan. KUBER arrived off the coast of Mumbai unscathed and unaddressed by maritime authorities on the evening of 26 November. The master was bound and his throat slit. The raiding party assembled their inflatable Gemini boats (counts vary from one to three), transferred their equipment and began the 4 NM insert under cover of darkness. KUBER was left adrift with a GPS, satellite phone, and other materials that would prove instrumental in developing the backstory during the subsequent investigation.

It’s unknown where the inflatable craft parted company (assuming there was more than one), but multiple beach landing sites were used. In the truest sense of camouflage, the boat(s) were not colored black and green to blend into the night, but bright yellow to blend

into the menagerie of local craft- undoubtedly a result of the early reconnaissance. At one site the operatives cheerfully claimed to be college students. At the other site they responded gruffly to locals, telling them to mind their own business, possibly even displaying their weapons. They continued unhindered in both cases, abandoned their craft on the beach, and shortly thereafter waltzed into history as executioners in a horrific raid.

To recap: LeT reconnoitered by sea, trained on Pakistan’s inland waterways, departed a major sea port (Karachi), hijacked a fishing vessel illegally operating in Pakistani waters/EEZ, transited unmolested across 500 NM of Indo-Pak littorals, amphibiously inserted into the Mumbai metropolis unchallenged, and came ashore unnoticed save for a handful of local fishermen accustomed to illicit maritime activity.

LeT violated the Indo-Pak littorals with impunity and conducted a raid heralded as a wake up call for maritime terrorism. This raid indeed required a great deal of competence, but VEOs embracing riverine or littoral waters as a maneuver space should not have come as any surprise. Then and now, the Niger River Delta and the Gulf of Guinea were abused by criminal organizations on a daily basis; Philippine waters were plagued by Abu Sayyaf; Colombian Riverines routinely battled the FARC and AUF; and in the U.S.’s backyard were organizations trafficking drugs, money, and violence through the Caribbean, Western Pacific, and Rio Grande. Oceans and waterways are indeed the vital connective tissue of the world, but they are open for both legitimate and illegitimate business alike.

So how do nations prevent VEOs from gaining an advantage in the maritime domain? First, by viewing the fight against irregular enemies as more than a footnote to the Mahanian themes used to define influential maritime powers. Thirteen years of war in Iraq and Afghanistan have taught our landward compatriots a valuable lesson: maneuver warfare is on the back-burner and irregular adversaries are in. The world’s maritime agencies must adapt that lesson themselves or risk learning its reality firsthand in the aftermath of attacks like Mumbai, the USS COLE, or SUPERFERRY 14.

One way of adapting that lesson would be borrowing two key themes from counterinsurgency: presence and engagement. Simply put, government authority must be present to win. That’s easier said than done when talking about enormous littoral and riverine areas. The key must then be cooperation. Within a country, that means developing a culture of partnership amongst government agencies (e.g. Customs, Coast Guard, local law enforcement) to supplement each other’s presence and intelligence efforts. No one agency can be everywhere, but a network of agencies can cover waterspace far more effectively. That cooperation and partnership must also be extended across national borders since, as we have seen, VEOs are not bound by such borders. Here we can find a blend of Mahanian themes and irregular fights- countries who can project seapower beyond their local shores can train and enable

the local seapower partner nations, thereby strengthening both. But they must have the right tools (i.e., riverine and littoral units) with the mindset for the job, neither of which can be best employed until irregular warfare moves beyond its footnote status.

Next, local maritime communities must be engaged. The fishing and merchant culture which was mentioned earlier as giving rise to the permeable maritime environment may be the best asset for monitoring it. These tradesmen have numerous networks, both formal and informal, that if partnered with or sourced by human intelligence professionals may reveal nefarious activity (e.g., combat training on Mangla reservoir or strangers who are out of place in Mumbai). Additionally, reliable engagement builds trust, which in turn builds security by aligning the interests of local communities and lawful government for mutual benefit. If the government is the trusted partner of the community, then this is precisely anathema to the VEOs which wish to destablize the community or exploit the disconnect from government to conceal their operations.

VEOs and irregular warfare in the maritime domain are not up-and-coming prospects, they have been here for some time. High-visibility attacks such as the Mumbai raid bring them to the foreground every so often, but after the 24-hour news cycle returns to mundane matters these VEOs continue to skillfully exploit the world’s waterways. There is, frankly, nothing new about what has been said here. But for the time being, these suggestions bear reiterating so we can fuel the discussion and move the ball forward.

Alan Cummings is a 2007 graduate of Jacksonville University. He served previously as a surface warfare officer aboard a destroyer, embedded with a USMC infantry battalion, and as a Riverine Detachment OIC. The views expressed here are his own and in no way reflect the official position of the U.S. Navy.

This week, we discuss naval development in West Africa with

This week, we discuss naval development in West Africa with