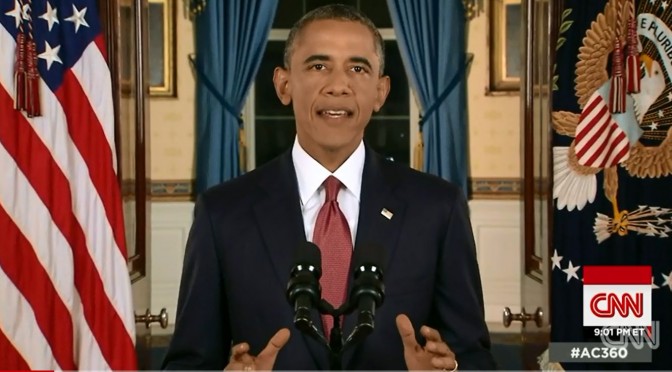

This piece was written in response to the Presidential address on ISIL and as part of our Strategic Communications week.

13 years ago America woke up to the Long War. September 10th was a sadly appropriate time for the President to address the continuation of the conflict: ISIL – the message of the speech was that this Long War will continue to be so.

As a piece of strategic communication, the speech laid out something best said by .38 Special:

Just hold on loosely

But don’t let go

If you cling too tightly

You’re gonna lose control

Your baby needs someone to believe in

And a whole lot of space to breathe in

The president’s intent was to explain the threat of ISIL, then walk the fine line of both destroying ISIL and avoiding the entanglement he sees in America’s thirteen years of ground war. In short, America will destroy ISIL, but America will not be the one to destroy ISIL – America will look to Arab partners, the Iraqi military, and the Syrian opposition, with the support of American advisers and airpower.

Let’s go into the details of looking at this speech, not for the policy, but as a piece of strategic communication.

To Everyone:

ISIL Is a Threat & Will Be Destroyed

While we have not yet detected specific plotting against our homeland, ISIL leaders have threatened America and our allies. Our intelligence community believes that thousands of foreigners, including Europeans and some Americans, have joined them in Syria and Iraq. Trained and battle-hardened, these fighters could try to return to their home countries and carry out deadly attacks.

This was considered by many the President’s moment to explain, particularly to the American people, explicitly the threat posed by ISIL, which he did by drawing the thread between opportunity, capability, and intent: the proven brutality and capability of ISIL, the stated aims, and their ability to get people of bad intent to us. This was likely aimed at European audiences as well.

I have made it clear that we will hunt down terrorists who threaten our country, wherever they are… This is a core principle of my presidency: If you threaten America, you will find no safe haven.

That message and its purpose probably doesn’t need any explanation.

To Middle Eastern Actors in General :

We’ll Be Holding On Loosely

This is not our fight alone. American power can make a decisive difference, but we cannot do for Iraqis what they must do for themselves, nor can we take the place of Arab partners in securing their region…

…This counterterrorism campaign will be waged through a steady, relentless effort to take out ISIL wherever they exist, using our air power and our support for partners’ forces on the ground.

Whether we can rely on the emergence of an enemy’s enemies coalition or an inclusive Iraqi government is to be seen, but this speech was likely meant as a final signalling to those in and around this cross-border conflict that the US will not be the one to “contain” this situation, and that the ongoing proxy war may threaten to consume all of them. The thinking may be that regional actors, once realizing the US will not “swoop in” will turn upon this conflict’s most disturbing symptom rather than each other.

No particular partners are mentioned other than the new Iraqi government, Kurdish Forces, and the vague “Syrian opposition” – the particulars of a specific Syrian opposition group, Iran, Turkey, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and many of the gulf states who choose to playing a part in extending this crisis are left out. This is likely on purpose, requiring no explanations of whose name was said, left out, or why.

Iraqi and Kurdish forces.

This is a side note to the more general trend, but the division of Iraqi and Kurdish forces should be recognized in the language. This could be a natural result of the bifurcation of the two forces’ effort in fighting and the desire to recognize the enormous contribution of the Kurds or a more subtle political intent.

To Congress:

But We Won’t Let Go

We will degrade and ultimately destroy ISIL through a comprehensive and sustained counter terrorism strategy.

That the US is now firmly aimed at ISIL and alot of resources, thought not troops, will be aimed in their direction. This not surprise to anyone – more importantly, the president communicated two specific points to Congress: he needed not seek their specific approval, but wanted to engage them & desperately wishes for them to expand their engagement in Syria.

I have the authority to address the threat from ISIL. But I believe we are strongest as a nation when the president and Congress work together. So I welcome congressional support for this effort in order to show the world that Americans are united in confronting this danger…

…It was formerly al-Qaida’s affiliate in Iraq and has taken advantage of sectarian strife and Syria’s civil war to gain territory on both sides of the Iraq-Syrian border.

This is pretty clear – some have speculated the president would seek Congress’s approval. He, fairly safely, presumes to tacitly have it amidst the unclear debate some are having on whether he needs it explicitly. Likely, this is also why he mentioned ISIL’s association with al-Qaida.

Tonight, I again call on Congress, again, to give us additional authorities and resources to train and equip these fighters. In the fight against ISIL, we cannot rely on an Assad regime that terrorizes its own people — a regime that will never regain the legitimacy it has lost.

Here the President is extending the discussion from earlier discussions on involvement in Syria – this is a point he does not plan on giving up, though in this speech it was buried in the larger narrative of his over-arching strategy. Having previously discussed the brutality of ISIL, he wishes to show how Assad cannot be a partner in their defeat – having already shown the same brutality. Realists would debate this point – but the president illustrates throughout the speech an intent to engage soft power and counter ideology. This will be something he will continue to push in the future.

To the American People:

Won’t Cling Too Tightly, and Lose Control

The president is trying to establish certain foundational points here with the American people for their support:

As I have said before, these American forces will not have a combat mission. We will not get dragged into another ground war in Iraq…

…I want the American people to understand how this effort will be different from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. It will not involve American combat troops fighting on foreign soil.

1.) The US will not go full-bore into this conflict, “returning” or being “dragged” back into what they’ve been used to for a decade. This was the great fear when the Syria debate arose, and one the President would like to avoid. This is likely meant to “cut off at the pass” the likely debate of mission creep, or at least hold off discussion and a potential negative consensus if it does happen.

We can’t erase every trace of evil from the world and small groups of killers have the capacity to do great harm…

…It will take time to eradicate a cancer like ISIL.

2.) Keeping expectations realistic. The strategy laid-out is, indeed, a long one – and the statement that “we can’t erase every trace of evil from the world” is an acceptance that many more like-threats will come in the future. The President likely wishes to avoid any sense of triumphalism or expectation of a quick victory that will later be dashed and undermine support for the mission.

…any time we take military action, there are risks involved, especially to the servicemen and -women who carry out these missions.

3.) This is to set up the expectation of risk – with personnel in-theater and aircraft overhead, any discussion of this being “low risk” would immediately undermine the mission if/when our people are killed/kidnapped by ISIL or if an aircraft were to go down. The reality-check on the longevity and risk of this conflict up front may not create the initial surge of support, but will create a more sturdy and realistic appreciation for what we’re doing that may last longer.

To Middle Easterners & Potential Western ISIL “Converts”:

Middle East has America to believe in,

But whole lot of space to breathe in.

As stated throughout the speech—the United States is committed to the region, but the dialogue of “airpower”, standoff “counter-insurgency”, and advisors is to push the narrative that the US will not be occupiers again. This is likely a long-shot attempt to communicate to those on the fence about ISIL or worried about “western imperailism.” Part of that denial of a “imperialist” or “holy war” narrative is also the continued emphasis the United States is placing on ISIS not being “Islamic” and the United States not being at war with Islam. It is unlikely that this message would reach anyone in the conflict zone.

It may, however, be for those in Western Nations or more stable neighbors to the conflict who would follow ISIL’s new social media campaign into the maw of jihad, as Anwar al-Alwaki convinced some westeners to do.

Overall:

Some will argue with the strategy itself, as well as the accuracy/value of allusions to Somalia and Yemen (as I sit here watching talking heads on CNN), but as a piece of stand-alone strategic communication for the plan being put forward, the speech was a straight-forward. It clearly illustrates the reasons the US is engaged with ISIL and the commitment of the US to its own safety, as well as a commitment to allies -willing- to commit to their own safety,

Few communications are more “strategic” than those that come from the Bully Pulpit, and this was a solid piece of that kind of communication. Whether this 80’s classic of “Hold on Loosely, But Don’t Let Go,” is right plan for the US? That is for us to argue and, as time goes on, see.

Matthew Hipple is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content and an officer in the United States Navy. His opinions do not necessarily reflect those of the US Government, Department of Defense, or US Navy – but sometimes they do.

Alex Clarke interviews

Alex Clarke interviews