By CAPT Robert N. Hein, USN

The call of the ocean has enticed generations to explore, and at times exploit her domain. Ninety percent of world commerce transits the oceans. Cruise ships represent a $40 Billion industry, and 30% of the world’s oil originates offshore. It is no wonder criminals and terrorists also feel drawn to the sea. As these groups expand their reach, the question is: When will ISIS and other terrorist organizations bring their brand of mayhem to the oceans?

A senior NATO Admiral, VADM Clive Johnstone, recently expressed concern that ISIS desired its own maritime force to spread its nefarious activities into the Mediterranean. These activities could include launching attacks against a cruise liner, oil terminal, or container ship. Soon after VADM Johnstone’s comments, Former Supreme Allied Commander and retired Admiral James Stavridis weighed in with his own concerns about ISIS entering the maritime domain: “I’m surprised [Islamic State militants] have not, as yet, moved into the maritime world and gone after cruise ships, which I think are a logical and lucrative target for them.”

While ISIS’ maritime capabilities have been limited to date, this has not been true of all terrorist organizations. ISIS’ predecessor, Al Qaeda, launched a vicious and successful attack against the USS COLE in October 2000. Somali pirates experienced tremendous success at sea for years, but strong responses from the international community and force protection measures by the maritime industry have limited further successful attacks. ISIS’ limited attempts at sea have achieved some effects though, such as the shore-launched rocket attack on an Egyptian naval ship in August. Additionally, there was a recent attempt by ISIS to conduct an attack from the sea against a Libyan oil terminal, but it was thwarted by Libyan security forces.

Footage of ISIS affiliated insurgent group launching missile at Egyptian Timsah class patrol boat in July 2015.

How Real is the Threat?

The lure of expanding operations into the maritime domain is enticing to terrorist groups. The relative isolation is real, and external response is limited. Terrorist attacks on land receive a rapid government response, in large numbers, and with many assets to thwart an attack. Case in point is the Al Qaeda attack at a luxury hotel in Burkina Faso in January 2016. Three members of an Al Qaeda group took 126 hostages and killed two dozen more before security forces stormed the hotel, killing the terrorists and freeing the hostages. A logical extension of the attacks in Burkina Faso would be an assault on a large and remote or underdefended luxury hotel- such as an underway cruise ship. The narrative ISIS hopes to convey from attacking a cruise ship at sea is akin to many horror movies: a captive victim with nowhere to turn for help.

Following VADM Johnson’s prediction, the Cruise Line International Association quickly stepped in to reassure its passengers that cruises are still safe, but are they? The last successful terrorist attack against a cruise ship was 30 years ago by Palestinians. Their original intent was to use the Achille Lauro as transport to Ashdod, Israel, to launch a terror attack ashore. This plan rapidly changed when a crew member discovered the terrorists/attackers cleaning their weapons.

While the Achille Lauro incident increased levels of security in the cruise ship world, threats to the cruise industry remain. In March 2015, cruise ship tourists visiting a museum during a stop in Tunis were attacked. Cruise lines are quick to cancel port visits in global hot spots, and most employ internal security forces. However, the allure for terrorists remains. Al Qaeda made plans as early as 2011 to capture a cruise ship and execute its passengers. Fortunately, those plans have failed to come to fruition as terrorist groups have found the task is harder than it looks.

While attacks on the open ocean remain a challenge, coastal attacks are more feasible. The Pakistani terrorist group Lashkar-e-Taiba launched an attack in 2008 against Mumbai. They hijacked an Indian fishing boat and launched 10 terrorists ashore, ultimately killing 166 and injuring almost 500. The lack of a strong Coast Guard in both India and Pakistan certainly contributed to the terrorists’ success, and served as a wakeup call. In response to the Mumbai attacks, the Indian Navy was placed at the apex of India’s maritime security architecture and made responsible for both coastal and oceanic security. Since then, the Indian Navy has successfully prevented further attacks. However, even with the additional forces, indications persist that ISIS may be trying to infiltrate India by sea, disguised as fishermen.

Arguably, the most successful terrorist group on the sea was the Sri Lankan separatist group, the Tamil Tigers. In his treatise A Guerrilla Wat At Sea: The Sri Lankan Civil War , Professor Paul Povlock of the Naval War College describes how at their strongest, their maritime branch (the Sea Tigers) boasted a force of 3000 personnel with separate branches for logistics, intelligence, communications, offensive mining, and — every terrorists’ favorite — the suicide squad. They conducted sea denial with great success, even demonstrating the ability to sink Sri Lankan patrol boats using fast attack craft and suicide boats.

The Tigers continued their attacks against Sri Lanka for 20 years until the Sri Lankan Navy was able to effectively neutralize them. The Sri Lankan Navy now has a formidable maritime patrol, but not before they lost over 1000 men to the Sea Tigers. Hardly a day goes by without illegal fishermen being chased away or arrested by the Sri Lankan government, who is ever mindful that their waters could again be used for more nefarious purposes.

Sometimes terrorists’ appetites are far bigger than their stomachs, as was the case in September 2014 when Al Qaeda operatives attempted to hijack a Pakistani frigate. If successful, it would have had epic implications. However, the attempted takeover was thwarted by a sharp Pakistani gunner who noticed the inbound boat did not have standard issue gear. He engaged, destroying the terrorist boat, while commandos onboard the frigate subdued crew members sympathetic to the terrorist cause.

Defeat and Deter

Operating in the maritime domain is far more challenging than operations on land. The Somali pirates were originally fishermen and familiar with operating at sea, but it still took them years to develop an offshore “over the horizon” capability. The lack of successful attacks at sea by terrorist organizations in spite of their indicated desire is at least a partial validation of the efforts made by the maritime security community.

The effective shutdown of piracy off Somalia served as a model for defeating maritime crime, showing coastal nations the effects of naval presence in deterring illegal behavior at sea. Malaysia has all but shut down sea crime in its waters, and blunted terrorist attempts to enter Malaysia by aggressively patrolling their coasts. Nigeria has similarly stepped up its game in the Gulf of Guinea where their navy stopped two hijackings in one week and separately announced they would soon take delivery of an additional 50 boats- both demonstrations of commitment to peaceful use of their waters. That doesn’t mean the work is over. ISIS, who has the funds for major purchases, is attempting to acquire naval capabilities like 2 man submarines, high powered speed boats, boats fitted with machine guns and rocket launchers, and mine planners made easily available by less discerning arms providers such as Korea, China, and Russia.

While the likelihood of near-shore attacks remains a possibility, including against cruise ships, the chance that ISIS will attack blue water objectives out of sight of land is still remote. However, the odds will remain remote only as long as the navies of the world continue to provide a credible presence on the oceans. When the seas are no longer effectively patrolled, terrorist organizations will take advantage of the same opportunities for freedom of maneuver at sea that they currently enjoy ashore.

Captain Robert N. Hein is a career Surface Warfare Officer. He previously commanded the USS Gettysburg (CG-64) and the USS Nitze (DDG-94). You can follow him on Twitter: @the_sailor_dog. The views and opinions expressed are his own and do not reflect those of the Navy or the Department of Defense.

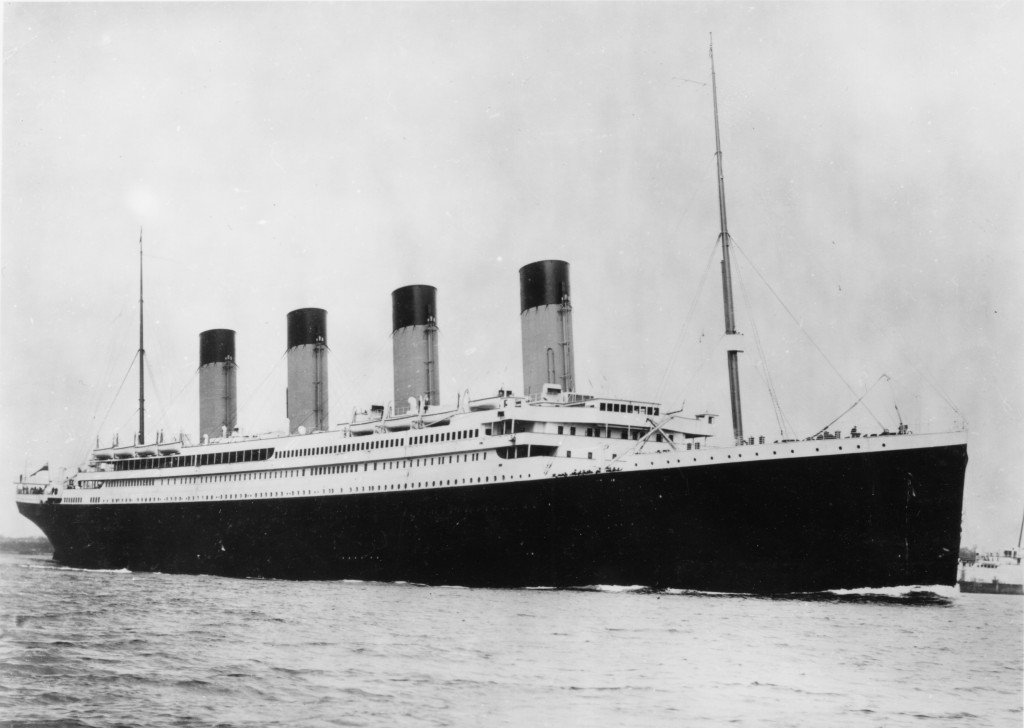

Featured Image: The U.S.S. Cole in 2000 after suffering an Al Qaeda attack in the port of Aden. 17 American sailors were killed, and 39 were injured.