In my last post I criticized those who overemphasize the size of a fleet as a measure of its operational effectiveness, using the historical example of the Royal Navy’s fleet modernization efforts prior to the First World War. I did not offer any alternate criteria by which to judge what an optimally sized U.S. Navy would look like. With discussions of what insights turn-of-the-century theorists such as Alfred Thayer Mahan and Julian Corbett would have on modern maritime strategy so popular right now, however, I thought there might be value to apply their models of sea power to evaluate the composition of today’s U.S. Navy.

Responding to a critique that the current fleet is the smallest it has been since 1917, Under-Secretary of the Navy Robert Work noted that the ability of the current fleet to accomplish its missions is as great as it has ever been, arguing that at a century ago “we didn’t have any airplanes in the fleet. We didn’t have any unmanned systems. We didn’t have Tomahawk cruise missiles.”

Critics of what they perceive as a too-small fleet claim that quantity is important because “presence” is necessary for command of the sea. On its face this is logical, as without enough combat power at the right spot and right time, victory is impossible. Having more ships makes it theoretically possible to concentrate a larger force at the decisive point, as well as providing more resources in more places to deter against the enemy, wherever they may be. The only restriction in a navy’s ability to provide presence is the amount of resources that a state has at its disposal.

Mahan was opposed to any notion of presence itself providing any particular utility, expressing a preference for offensive fleet action, even when that end was accomplished by a fleet inferior in total size to that of its foes. His optimal navy was “equal in number and superior in efficiency” to its enemies at the decisive point within “a limited field of action,” not necessarily everywhere. It protected national interests “by offensive action against the fleet, in which it sees their real enemy and its own principal objective.” Mahan would have not approved of an emphasis on presence as an objective, for his description of the undesirable alternative to his above strategy was one which requires the “superior numbers” needed to provide “superiority everywhere to the force of the enemy actually opposed, as the latter may be unexpectedly reinforced.” Trying to outnumber the enemy everywhere at sea is an impossible end state in any situation in which a pair of opponents have remotely comparable resources upon which to draw.

Corbett’s view of sea power is more compatible with the notion that presence is important. Corbett felt that what he called “Command of the Sea” was “normally in dispute” and that the most common state in maritime conflict was that of “an uncommanded sea.” In that context, presence in terms of more ships means that a navy can employ its forces in more places, with command thus achieved. It would be easier to achieve this state of command through presence in asymmetrical situations in which the smaller force is overmatched both in terms of quantity and quality.

War at sea often revolves around two factors: the ability to locate the enemy, and the ability to employ decisive force against the enemy first. Until navies began to use aircraft in the early twentieth century, the only way to locate an enemy fleet was to actually see it from onboard ship (or ashore). Until the introduction of wireless communications, the ability to pass any intelligence thus derived was also restricted to line-of-sight or the speed of a ship. Mahan noted the difficulty to locate and track a fleet when he said that they “move through a desert over which waters flit, but where they do not remain.”

By having more ships (assuming they effectively employed them), a navy would theoretically have a better chance to locate the enemy on favorable terms. Nelson could sail across the Atlantic (and back again) and around the Mediterranean without finding the French fleet because his “sensors” were limited to the visual range of his fleet. The conflict between the German and British navies during the First World War was largely one in which the two fleets were unable to achieve their tactical objectives because they could not find each other (at least under tactically favorable circumstances). In a more modern example, the American victory at Midway was made possible by SIGINT. Because the US Navy knew that the Japanese intended to attack Midway, its fleet was placed in a position where they were more likely to find the Japanese first (even then however, each fleet was limited in their ability to locate the enemy to the range of their aircraft).

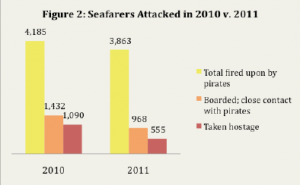

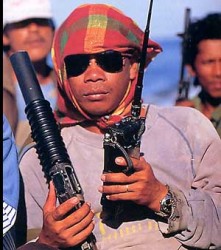

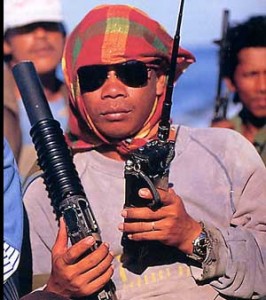

A smaller fleet which is enabled in its ability to project combat power over a larger area through technology to engage the enemy on its own terms would seem to be just as important as a large fleet. Today’s U.S. Navy, with access to a historically unprecedented web of information made possible by sensors and surveillance assets in the air, on the surface and under the water, has the ability to win battles against a capable enemy because those sensors mean it can deliver ordnance against enemy targets first. However, one of the more astute criticisms of Under-Secretary Work’s defense of the current fleet size is that it only works in war, not other situations in which it is not clear “whether replacing ships with aircraft is a legitimate approach towards maritime battlespaces in peacetime when that same effort has been largely ineffective dealing with other low intensity maritime problems like narcotics and piracy.”

The debate over presence revolves around strategy and objectives, and whether the size and composition of a fleet matches up with those objectives. If the U.S. maritime objective is the ability to operate at sea in any contested theater, then having a sensor-enabled battle force in which surveillance assets make decisive action possible before the enemy can act is more important than surface presence in terms of many ships. Conversely, if the most important objective is to provide maritime security against illicit actors such as pirates or drug smugglers, then presence is more important. As the linked post above from Galrahn notes, a UAV can enable kinetic offensive operations from another platform located far away, but it cannot board a suspect vessel and detain the crew.

The debate between the advocates of presence and a high-end battle force is actually one over the relative importance of the Maritime Security and Sea Control missions, and the resources devoted to each at the expense of the other. Unfortunately, without a crystal ball, there is not a straightforward answer as to which is the more necessary one for the US Navy to conduct.

Lieutenant Commander Mark Munson is a Naval Intelligence Officer and currently serves on the OPNAV staff. He has previously served at Naval Special Warfare Group FOUR, the Office of Naval Intelligence and onboard USS ESSEX (LHD 2). The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official viewpoints or policies of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.