By Tuan N. Pham

China just concluded the Second Belt and Road Forum (BaRF) in Beijing 25-27 April. The theme was “Belt and Road Cooperation, Shaping a Brighter Shared Future.” The forum aimed to bring greater and improved cooperation under the ambitious and expansive Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) consisting of 126 countries and 29 organizations that have signed cooperation agreements with China, and generated a total trade volume of $6 trillion to date. 36 foreign leaders attended this year’s forum – up from 29 two years ago. However, notably absent were the heads of state or government from Washington, Tokyo, Seoul, Canberra, New Delhi, London, Paris and Berlin.

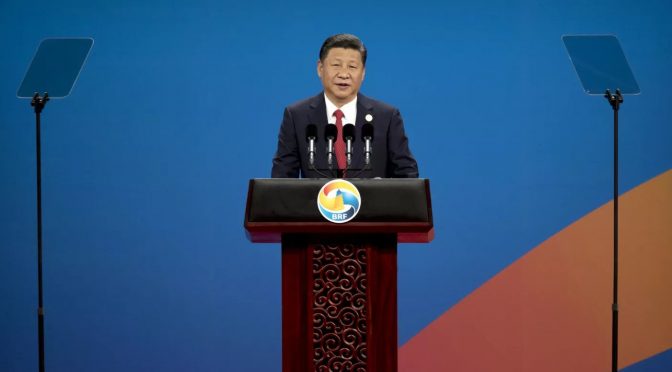

In the keynote speech, Chinese President Xi Jinping pledged to recalibrate the global infrastructure program and enhance transparency to ensure the financial sustainability of the many BRI projects and respond to the growing chorus of international criticism that they burden and exploit developing countries with onerous debt. The content and manner of the conciliatory speech marks an acute departure from past confident tones to promote and advance the program, and perhaps a tacit acknowledgement that his signature initiative lost ground and momentum in 2018 both abroad and at home, requiring a reset (BRI 2.0). What were the key takeaways, what has changed since the inaugural BaRF in 2017, and more importantly, what’s next for Washington?

Key Points of Xi’s Speech

Xi began his speech with a line from a classical Chinese poem – “spring and autumn are lovely seasons in which friends get together to climb up mountains and write poems” and an old Chinese proverb – “plants with strong roots grow well, and efforts with the right focus will ensure success.” Xi then proceeded to assure the audience and the broader international community with familiar BRI themes that were pervasive throughout Beijing-controlled media before, during, and after the forum, “we need to be guided by the principle of extensive consultation, joint contribution, and shared benefits; seek open, green, and clean cooperation; and pursue high standard cooperation to improve people’s lives and promote sustainable development.” Xi next promised structural reforms – similar to those discussed in the ongoing U.S.-China trade talks – “to expand market access for foreign investment in more areas; intensify efforts to enhance international cooperation in intellectual property protection; increase the import of goods and services on an even larger scale; more effectively engage in international macro-economic policy coordination; and work harder to ensure the implementation of opening-up related policies.”

Xi concluded his remarks with another Chinese adage – “honoring a promise carries the weight of gold” – while making commitments to “implement multilateral and bilateral economic and trade agreements reached with other countries; strengthen the building of a government based on the rule of law and good faith; put in place a binding mechanism for honoring international agreements; revise extant Chinese laws and regulations to expand the opening-up of the country; overhaul and abolish unjustified regulations, subsidies, and practices that impede fair competition and distort the market; treat all enterprises and business entities equally; and finally foster an enabling business environment based on market forces and governed by law.” All in all, Xi’s 2019 speech was a sharp contrast from his triumphalist speech during the inaugural BaRF two years ago.

International Monetary Fund Managing Director Christine Lagarde welcomed the shift in Chinese rhetoric, telling the forum after Xi’s speech that the initiative could “benefit from increased transparency, open procurement with competitive bidding, and better risk assessment in project selection” while cautioning that the infrastructure program “should only go where it is needed and where the debt it generates can be sustained.”

Behind the rhetoric was a laundry list of deliverables to demonstrate commitment to BRI 2.0 and stem the growing skepticism of BRI’s benevolence and benefits. The list includes 283 initiatives proposed or launched by Beijing – bilateral and multilateral agreements signed during or immediately before the BaRF, multilateral cooperation mechanisms under the BRI framework, investment projects and project lists, financing projects, and projects by local authorities and enterprises (supposedly $64 billion worth of deals).

“Initial” ground assessments painted the BaRF as a “chaotic” diplomatic conference lacking a clear schedule and sufficient content, exacerbated by tight media control thereby making it difficult for the host to project openness (transparency) and falling flat for many of those attending. Television broadcasts of a roundtable discussion on Saturday joined by attending world leaders featured only the opening remarks by Xi and the livestream was cut abruptly before any of BRI countries had a chance to speak. “So basically this forum, to me, was a one-day publicity stunt for China…not enough content for a three-day event,” stated a person close to the forum’s organization. A European delegate added that the lack of a clear schedule often left attendees either waiting for hours on end or scrambling to catch up after an event started suddenly.

What Has Changed

China originally envisioned the BRI as a global network of ports, roads, railways, pipelines, and industrial parks, largely built by Chinese corporations. But as the initiative rapidly expanded beyond infrastructure construction to encompass additional underlying political and military objectives as evident by Beijing’s plan to build military bases around the world to protect its growing investments along the various Silk Roads, Western governments began criticizing the BRI for promoting and advancing opaque financial deals that give Beijing undue political leverage by encumbering developing countries with unsustainable financial burdens as well as engendering other risks to the recipient states. These risks can include the erosion of national sovereignty, disengagement from local economic needs, negative environmental impacts, and significant potential for corruption. The complaints steadily grew louder and gained traction over the years, culminating in an increasing number of Asian and African nations suspending, cancelling, or renegotiating BRI projects. Just last month, Beijing cut its price for a multibillion-dollar railway in Malaysia by roughly a third, reviving a project that had been stalled by concerns over debt and corruption.

At the onset of and throughout the BaRF, Beijing de-emphasized big-ticket infrastructure projects in its BRI public diplomacy (public relations) campaign and made more pledges to ensure sustainable (responsible) lending and fight corruption. As part of the recalibration, Chinese government officials negotiated with foreign governments to draw up lists of official BRI projects, promising more BRI transparency, and trying to attract more private-sector money to offset the disproportionate government funding, reduce the domestic fiscal risk, and diminish the perception that the initiative was just another political tool for global dominance. In his keynote speech at this year’s BaRF, Xi underscored the latter by inviting foreign and private-sector partners to contribute more funding and did not make any new pledges of Chinese financing.

What’s Next

China’s promises for a revamped BRI 2.0 will require further monitoring and scrutiny. Hence, Washington and the greater international community should be wary of the ubiquitous “rebranding” by the Chinese state-controlled media and of the vague, ambiguous, and uncertain assurances and deliverables that Beijing may be dangling as an effort to reframe the BRI. China may be presenting a kinder persona to stem the growing skepticism and avoid making longer-term structural BRI reforms, which Beijing does not want to do unless coerced to do so. From the Chinese Communist Party’s perspective, the structural changes will weaken the BRI, undermine China’s global competitive advantage, slow the Party’s deliberate march toward the Chinese Dream of national rejuvenation, and keep Beijing from realizing its strategic goal of achieving global influence and ultimately global preeminence. All in all, these promises and assurances are politically expedient but will remain empty without greater transparency and enforcement – the same points made in The Diplomat article “On Looming U.S.-China Trade Deal, Actions Speak Louder Than Words…Talk without the support of action means nothing. Enforcement will be the key to any deal.”

So how should Washington respond? Perhaps the best response is a BRI of its own as proposed by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, this author, and others. The United States could offer a compelling and alternate economic vision, resourced, and sustained over time. The world needs more infrastructure than any one state can provide, and dissatisfaction and disenchantment with the BRI provides a strategic opportunity for America to work with its allies and partners to deliver high-quality and affordable infrastructure without Chinese conditions. Washington should also start seriously thinking and preparing (contingency planning) for the possibility of a BRI collapse.

At the end of the day, the old Arabian proverb “a promise is a cloud, fulfillment is rain” is apropos. Trust but verify, and plan accordingly for contingencies.

Tuan Pham is a seasoned China watcher with over two decades of professional experience in the Indo-Pacific and is widely published in international relations and national security affairs. The views expressed are his own.

Featured Image: Chinese President Xi Jinping speaks during the opening ceremony of the Belt and Road Forum at the China National Convention Center (CNCC) in Beijing, Sunday, May 14, 2017. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)