Crossing the Baltic Sea recently from Gdynia to Karlskrona, both major naval bases, I had the opportunity to observe ships of both the Polish and Swedish navies. By coincidence, I had just finished reading Tom Kristiansen and Rolf Hobson book Navies in Northern Waters. I began to wonder how a big navy could benefit by observing these small fleets. Smaller navies commonly look at their big partners in efforts to predict future trends and developments.

Small navies should be aware that they operate on the edges of major naval war theories like those developed by Mahan or Corbett. Such theories were based on the historical experience of leading navies at their times. Although it is possible to imagine a “decisive battle” between offshore patrol vessels (OPVs) or fast-attack craft (FACs) (see Israeli-Arab wars), most probably small powers and their navies will balance between global or regional powers, allied with one of them against another or left alone against superior power. From a cooperative naval power point of view they could nicely fulfil diplomatic or constabulary roles. But there are also other areas worth mentioning, where small navies’ views, development, and operational experience could be of interest to leading navies. Studying small navies provides:

- The potential to turn knowledge of small navies into a theoretical framework would enhance our understanding of special cases in major naval theories: This could be of some interest in narrow seas and littoral areas, for example. In this year’s BaltOps exercises, the U.S. Navy was represented by an Aegis cruiser USS Normandy, but in coming years a more frequent participant will probably be an LCS. Participation in such exercises would offer the opportunity to observe how LCS works together with mine hunters, FACs and corvettes from regional, coastal fleets in scenarios similar to Northern Coast, perhaps somewhere in Finnish archipelagos. Such scenarios much more closely resembles Capt. Wayne Hughes’ works and would offer expertise applicable elsewhere.

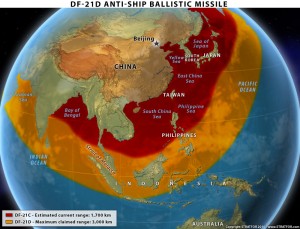

- Insight into the political decisions related to small navies’ development, roles, and applications: Not a direct benefit for the U.S. Navy, but helpful in arranging and maintaining networks of alliances, if and when needed. In literature the PLAN navy is often described as proficient in anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities. Is this a view smaller navies in the South China Sea region share? Even regional powers like India or Japan could hardly fear the PLAN’s current A2/AD capabilities. Unhindered access of the U.S. Navy to some specific waters doesn’t translate directly to feelings of strengthened security among smaller allies. The relation is more complex and understanding their, sometimes hidden motives, should give better results.

- The opportunity to foster innovation: Small navies act under pressure of constraints not unknown to big navies, but the constraints can be even greater. In a small navy, a proposal to build a well-armed corvette can trigger hot discussions not only about the budget but even also about national policy. Everything is condensed. Links between strategy, tactics, budgeting, and force structure are more visible. Maybe this is the reason why small navies have to be both pragmatic and innovative at the same time. A good example of the pragmatic approach I found in Navies in Northern Waters is the fact that in the 18th-century both Swedish and Russian navies still used oared galleys. Examples of innovation are not limited to modularity or ships like Visby. Take a look at the Latvian navy, non-existant some 20 years ago. It acquired used ships from different navies and created the core of mine warfare and patrol capabilities. This was very pragmatic, and the first new construction, the economic SWATH designSkrunda, shows great attention to versatility.

- Educational value: Let’s use an example. Say the task is to propose a force structure for a navy that’s been neglected in recent years. Historically, the military conflicts in this country have been decided on land. The adjacent narrow sea has an average depth of around 170 feet. The navy has no independent budget, but is instead centralized in the DoD’s. The yearly shipbuilding budget is forecasted at $200 million and the navy is given the time span 20 years to build the fleet. Although there is a shipbuilding industry, it has never built sophisticated warships. Anyone attempting to solve this kind of problem gains a much greater understanding of decisions faced by and made by senior staffs in the real world.

Przemek Krajewski alias Viribus Unitis is a blogger In Poland. His area of interest is broad context of purpose and structure of Navy and promoting discussions on these subjects In his country