By Andrew Walker

“Despite the inherent challenges, al-Qaeda can attack, has attacked, and will again attack maritime targets. Indications point to an acceleration of the pace of maritime terrorism, heralding a coming campaign. The propensity of al-Qaeda for patient and intricate preparation augurs a future sustained maritime terrorism campaign, rather than a continued irregular pattern of attacks” – (Ret) Captain Jim Pelkofski (Joint Operations Directorate at US Fleet Forces Command; Current Pentagon Force Protection Agency’s director of anti-terrorism and force protection)

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

The American naval historian and strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840-1914) claimed in his Influence of Sea Power on World History that strong naval and commercial fleets are essential to the nation’s military power. In a post September 11th society, governments have dedicated heavy resources to assessing the vulnerability of their homelands to acts of terrorism. The number of terrorist attacks in the maritime environment is proportionally small in comparison to the overall number. However, (Ret) Admiral Sir Alan West, The UK’s First Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Staff deemed maritime terrorism “a clear and present danger” that may “potentially cripple global trade and have grave knock-on effects on developed economies.” The probability of a terrorist attack on a major North American port may be low for some security analysts, but given the catastrophic effect an attack via improvised explosive devices (IEDs), hijacking and using a ship as a weapon, or biological weapons could have on such “economic chokepoints,” significant focus must be placed on the subject.

As 95 percent of all global trade is shipped on water, great effort have been made to ensure that the maritime shipping system is as open and fluid as possible to guarantee a healthy and growing global economy. Ironically, the measures put in place to maintain an efficient maritime transport system also allow for glaring security gaps to be exploited by terrorist groups.

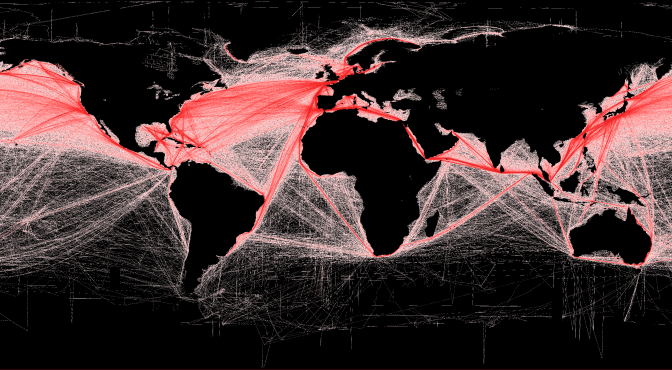

Major global trade routes and geographic chokepoints.

Historical Precedence

The bulk of historical analysis and research performed on maritime shipping has revolved around the risks that encompass containerized shipping, the likelihood of an attack on a shipping vessel, and the potential outcomes of these attacks. What complicates the assessment of potential attacks is the fact that there are seemingly countless avenues upon which to mount an operation; for example, attacks may range from the contamination of physical cargo on a vessel with biological or nuclear materials to the shipping of goods in order to finance terrorist activities. As such, maritime infrastructure and systems are both targets of, and potential shuttles for, maritime terrorism. Paramount to the study of an attack on the maritime trade industry is the understanding that an attack on a major port or shipping route could incapacitate the global economy.

The most notable historical examples of maritime terrorism come from the attacks on the USS Cole and the MV Limburg.

USS Cole

On October 12, 2000, while refueling in harbor in the Yemeni port of Aden, the USS Cole was the target of an al-Qaeda suicide attack delivered by a small vessel filled with explosives. Seventeen sailors were killed, and 39 were injured, making it the deadliest attack against the US Navy since Iraq struck the USS Stark in 1987. Through careful planning, al-Qaeda developed substantial on-shore infrastructure in order to train for the attack, ensuring training grounds were surrounded by fencing in order to shield the illicit activities from neighbours. Furthermore, al-Qaeda rented a harbor-front property to act as an observation post. Learning from past foundational mistakes of the failed January 3, 2000 attempt on the USS The Sullivans, where the explosives-heavy boat sank almost immediately upon launch, al-Qaeda properly modified the new suicide-vessel, painted it, laid a new floor, and refitted the insulation. The important lesson to derive from this attack was that al-Qaeda would learn to rehearse their operations, ensure their vessels had the appropriate arms, and would even conduct test runs, learning from past operational failures.

MV Limburg

The attack on the MV Limburg was an act of opportunity, as the initial plan targeted a US warship that did not arrive as expected. On October 6, 2002, two years after the attack on the USS Cole, the Very Large Crude Carrier (VLCC) weighing 300,000 dead weight tons (DWT) with a 2.16 million barrel capacity (carrying roughly 397,000 barrels from Iran to Malaysia) was unexpectedly attacked. The explosives-laden dinghy rammed into the starboard side of the tanker and caused extreme environmental and economic damage. Although the attack on the Limburg only resulted in one death, it caused insurance rates of Yemeni shippers to rise 300 percent and cut Yemeni port shipping volumes by 50 percent for a month after the attack. Consequentially, the attack caused the short-term collapse of shipping in the Gulf of Aden, ultimately costing Yemen to lose $3.8 million a month in port revenues. Additionally, the Limburg would spill 90,000 barrels of oil into the Gulf of Aden, causing great damage to the surrounding maritime environment. On a relatively small scale, the economic impact of the Limburg attack served as an indicator of the widespread effects an attack on maritime trade can have.

Rescue vessels attempt to contain the fire on MV Limburg.

Rescue vessels attempt to contain the fire on MV Limburg.

Supporting the contention that most terrorist groups are not “innovative but imitative,” often learning through emulation and technology transfer, the attack on the USS Cole can be seen as a copycat of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam’s (LTTE) May 4, 1991 attack on Abheetha, a Sri Lankan Navy supply ship. Given the devastating impact of the attack on the Limburg, it came as no surprise when the documents seized during the May 2, 2011 Navy SEAL raid on Osama bin Laden’s compound in Pakistan indicated that bin Laden and other senior al-Qaeda leaders had developed future plans to hijack oil tankers and blow them up at sea, aiming to harm the American economy in a period of already soaring oil prices.

Since 2004, actions have been implemented, predominantly through the International Maritime Organization, to limit the threats to notable security gaps in the maritime shipping system. Still, numerous openings exist, such as America’s priority on securing its Naval vessels rather than its comparatively unprotected shipping industry and the lack of communication between ports regarding cargo inspections. Although the measures in place to ensure a safe and functioning shipping network come at a high price, the meticulous preparation of modern terrorists, the variety of targets, and the catastrophic effects an attack on an “economic chokepoint” could have should provide substantial motivation to ensure that all bases are covered.

Choke Points

Although geographical bottlenecks or ‘chokepoints’ like the Straits of Malacca leave shipping vessels susceptible to attack, ports are the real ‘chokepoints’ in global trade.

Consider these facts, vessels as large as 5,000 TEU (Twenty Foot Equivalent) currently call Halifax to take advantage of the deep draft and easy year round access to port. Halifax is ideally located as the first port inbound to North America from Europe, the Mediterranean, and the Suez Canal; it is also the last port outbound from North America.

As various shipments reach the Canadian port, Halifax then acts as the strategic rail gateway to key Canadian, U.S., and Mexican markets.

The ports of Halifax and Prince Rupert are both extremely important to the economic well-being of North America.

The ports of Halifax and Prince Rupert are both extremely important to the economic well-being of North America.

Citing the historical evolution of maritime terrorism, and the internal growth and preparation of organizations such as al-Qaeda, assessing port security vulnerabilities would serve as a prudent insurance policy.

A troubling reality is that the direct and indirect violence caused by such an event would be difficult to quantify due to the extremely far reaches of the maritime trade network. One thing is for certain; the cost of inaction would be unquestionably greater than the current funding efforts to secure global ports[1].

This “Primer” serves as the introductory piece on a series concerning Maritime Terrorism in a North American context. As such a strategically important environment, the debate between the importance of economic fluidity and homeland security in the maritime domain must continue…

__________________________

[1] Since 2004, port-related security costs in the United States have been estimated at roughly 2 billion (USD). Although it is difficult to fully measure the costs of further developing maritime port security. (OECD)

This article was first published on the website of the Atlantic Council of Canada’s: http://atlantic-council.ca/publications/theme/maritime-security/

About the Author, Andrew Walker

Andrew Walker is a Maritime Security Analyst with the Atlantic Council of Canada. He is a recent graduate of Dalhousie University’s History and Political Science program, where he focused on Cold War History and International Security. Through this appointment, Andrew hopes to develop his skills in the fields of maritime security and intelligence studies, focusing in particular on maritime terrorism, homeland defence, and economic “choke points”. Any views or opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and the news agencies and do not necessarily represent those of the Atlantic Council of Canada. This article is published for information purposes only.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]