By Travis Howard

Lieutenant Stacey Alto sits in the Joint Intelligence Center aboard the Wasp-class Amphibious Assault ship USS ESSEX (LHD 2). As the Force Intelligence Watch Officer (FIWO), her job is to absorb relevant information related to current and future operations of the Essex Amphibious Ready Group, as well as the general intelligence within the operating theater. Her zero-client, virtual desktop environment (VDE) 6-panel display at her watch station allows her a single-pane-of-glass into Unclassified, Secret, Top Secret, and Coalition enclaves through the Consolidated Afloat Networking and Enterprise Services (CANES) network.

One of her watch standers, an Intelligence Specialist Second Class, approaches her desk with new information from the Joint Operations Center (JOC), the nerve center of ARG operations, announcing new orders from the fleet commander to enter the Gulf of Oman, which represents a shift in operating theater from their current position in the Arabian Sea.

Stacey goes to work immediately, enlisting the help of two Intelligence Specialists and one of the Information Systems Technicians standing watch in the Ship’s Signal Exploitation Space (SSES). She queries the onboard widget carousel on her CANES SECRET terminal. Using a combination of mouse, keyboard, and touchscreen, she pulls together several ready-made widgets and snaps them into place, each taking advantage of a pool of “big data” information stored on the ship’s carry-on Distributed Common Ground System-Navy (DCGS-N) and off-ship sources from the intelligence cloud. Her development work gets passed to the next watch team, as they set the application’s variables for data parsing, consolidating inputs, and terrain mapping to put together a relevant, real-time intelligence picture.

By the time Stacey returns to her watch station almost 24 hours later, the IT personnel in SSES have put the new application through the automated cybersecurity testing process and have released it to the onboard “app store,” which Stacey can now install on her virtualized, thin-client desktop within seconds. She calls the JOC, the Marine Landing Force Operations Center (LFOC), and the ship’s Combat Information Center (CIC) announcing the system’s readiness with separate logins at the appropriate classification level for each watch station. By the time ESSEX enters the Gulf of Oman, the application has mapped adversarial positions and capabilities, pulled from several disparate databases afloat and ashore, all at varying levels of classification necessary for operational planning throughout the ship.

Building a More Maneuverable Network Afloat

The above scenario is almost a reality, representing several emergent advances in network technology and application portability (the “mobility” factor) that the Navy will soon capitalize on: a hardware and network-layer software architecture known as hyper converged infrastructure (HCI). The performance and cost efficiencies realized by this architecture will pave the way for disruptive changes to how we maneuver the network across the entire spectrum of operations: as a business system, as a decision support system, and as a warfighting platform.

Hyper-convergence is the integration of several hardware devices through a hypervisor, which acts as an intermediary and resource broker between software and hardware. Independent IT components are no longer siloed but combined, simplifying the entire infrastructure and improving speed and agility of the virtual network.1 The advantages of HCI seem obvious, but the real disruptive effect is how we can build upon it. The opening scenario describes on-demand application development at the tactical edge. This is achievable through HCI efficiency and another emerging network process known as Agile Core Services (ACS), a joint software development initiative being built into several programs throughout the Navy and Air Force, and one that CANES (as the afloat and maritime operations center network provider) is leveraging.

ACS allows applications to use a common mix of services at the platform level, reducing cost and time of development but also forcing all applications to “speak the same language.” All that is needed to make on-demand, tactical application delivery a reality is a framework for plug-ins that takes advantage of big data we already have aboard ships and available at both the operational and tactical levels of war.

Previous articles in the United States Naval Institute’s magazine Proceedings have argued for thin-client solutions aboard warships,2 leveraging the CANES network program to ultimately achieve network efficiency that can remove “fat clients” (standard computer desktops) from the architecture to be replaced by thin or zero-clients (user workstation nodes with virtualized desktops and no onboard storage or input devices beyond keyboard and mouse). Removing clients from the equation eases the burden on shipboard technicians, consolidates the information security posture, and overall presents a more efficient network management picture through smart automation that makes better use of available manpower. HCI is the architecture solution that will eventually enable a full-scale, afloat, thin-client solution.

Hyperconverged.org is a website dedicated to delivering the message of advantages that HCI can bring,3 and lists ten compelling advantages that HCI brings to any IT infrastructure, to include:

- Focus on software-defined data centers to allow faster software modernization and more agile vulnerability patching

- Use of commercial off the shelf (COTS) commodity hardware that provides failure avoidance without the additional costs

- Centralized systems and management

- Enhanced agility in network management, automation, virtualization of operating systems, and shared resources across a common resource manager (such as hypervisor)

- Improved scalability and efficiency

- Potentially lower costs (caveat: in the commercial sector this may be truer than in the government sector, but smart contract competitions and vendor choices can drive down costs for the government as well)

- Consolidated data protection through improved backup and recovery options, more efficient resource utilization, and faster network management tools

The advantages of HCI are numerous, and represent the true next step in IT architecture that will enable future software capabilities. How can we, as warfighters, take advantage of this emerging technology? It cannot be overstated that our current processes for procuring and delivering software-based services and capabilities must be revamped to keep pace with industry and take advantage of the speed and agility that HCI brings.

Faster, More Efficient Application Development is the Next Step

In our current hardware development methodology, programs of record within the Department of Defense (DoD) have little difficulty determining a clear modernization path that fits within the cost, schedule, and performance constraints outlined by the DoD acquisition framework. However, software development is an entirely different story, and is no longer agile enough to suit our needs. If we can iterate hardware infrastructure at near the speed of industry, then software and application development becomes the pacing function that we must address before we can realize the opening scenario of this essay.

The key term when discussing the speed of system development is agility, defined by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) as “the speed of operations within an organization and speed in responding to customers…or reduced cycle times.”4 The federal government, DoD in particular, has been struggling with acquisition reform for some time, and with the signing of the National Defense Authorization Act in fiscal year 2010, Congress placed renewed emphasis on the need to transform the acquisition process for information technology. Several programmatic changes to acquisition helped (such as the approval of the “IT Box” programmatic framework in the joint requirements process), but the agility of software development and modernization remains challenged. Ensuring proper testing and evaluation (T&E) methodology, bureaucratic approval processes to ensure affordability, joint interoperability testing, and lengthy proof-in testing are just some of the processes facing software applications prior to gaining approval for full-rate production and fielding to the warfighter.

Matthew Kennedy and Lieutenant Colonel Dan Ward (U.S. Air Force), in a 2012 article for Defense Acquisition University, argued for agility in system development by discussing flaws in the current “agile software development” model.5 Developed in the early 2000s, this model is not as agile as the name would imply, and still defines requirements to be developed in advance, which doesn’t leave room for innovation or rapid, iterative changes to keep pace with the speed of industry. Exciting initiatives are being fielded in the commercial sector, such as cloud-based development and learning models, and mobility technology that many of the services would use to great effect. Innovative prototyping of disruptive technology at the service or component level of DoD, such as the now-disbanded Chief of Naval Operation’s Rapid Innovation Cell (CRIC), proved that there are operational advantages to emerging tech such as wearable mobile devices, if only we could “turn a tighter circle” within our acquisition framework and work with agility to field newer and better versions to the force.

Thankfully, we don’t have to reinvent the wheel when implementing a more agile software development framework; we must take lessons from industry and apply them to the unique needs of each of the DoD components. This may be easier said than done, but Kennedy and Ward, and indeed likely many other acquisition professionals and scholars, would agree that it is entirely possible if leadership demanded it, and the policies, procedures, and resourcing followed suit to support it. Kennedy and Ward offered a common set of software and business aspect practices to support agile practices that would allow a predictable, faster software refresh cycle (not just patches, but cumulative updates) to ensure software remains agile and relevant to the warfighter. Using small teams for incremental development, lean initiatives to shorten timelines, and continuous user involvement with co-located teams are just some of the practices offered.6

Improving our software development and modernization framework to be even more agile than it is now is necessary considering the recent industry shift to software-as-a-service and cloud-based business models. No longer will software versions be deliberate releases, but rather iterative updates such as Microsoft’s “current branch for business” (CBB) model. With this model, Microsoft envisions that Windows 10 could be the last “version” of Windows to be released, which will then be built upon in future “service pack-like” updates every 12-18 months. Organizations that do not update their operating systems to the latest CBB will be left behind with unsupported versions. Not only does such a change demand a rapid speed-to-force update solution for DoD, but it represents a disruptive process change that will ultimately allow us to reach the opening scenario’s on-demand tactical application process, leveraging big data in a way that units at the tactical edge have never done before – and in a way that may never have been imagined by the system’s original developers.

Hyper-convergence infrastructure, together with agility-based application development and modernization, represents a near-term possibility that will enable true innovation at the tactical level of war and put the power of information superiority into the hands of the warfighter. While re-developing the acquisition framework to achieve this may be difficult, it is entirely possible and, many would say, necessary if DoD is to keep pace with emerging threats, take advantage of emerging technology and innovation, and ultimately retain its status as the best equipped and trained force the world has ever known.

Artificial Intelligence: The Next AEGIS Combat System

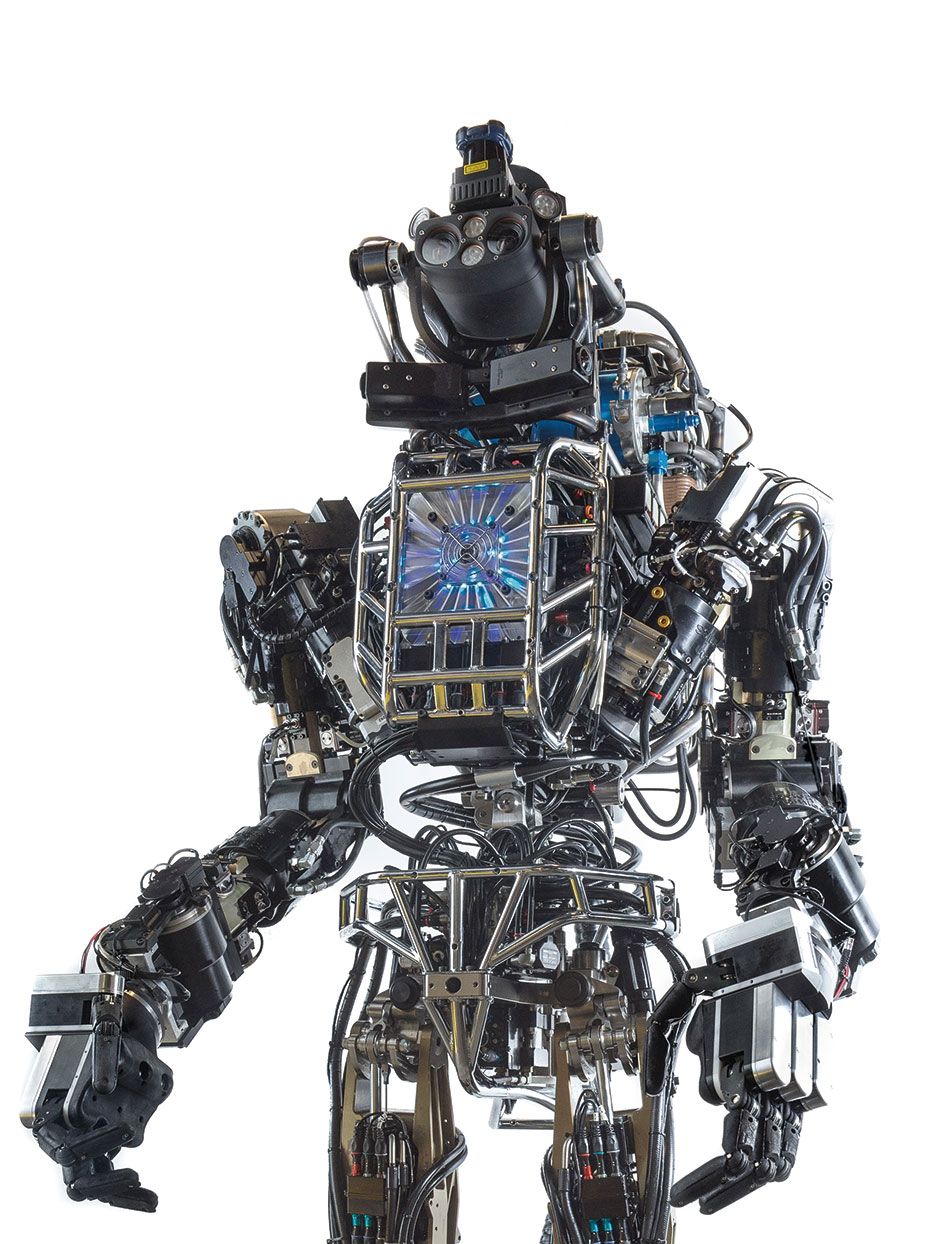

Now let’s imagine another scenario. USS LYNDON B. JOHNSON (DDG 1002), last of the Zumwalt-class destroyer line and used primarily to test emergent technology prototypes in real-world scenarios, slips silently through the South China Sea in the dead of night. She is the first ship in the U.S. Navy to possess Nelson, a recursively-improving artificial intelligence (RIAI). Utilizing an HCI supercomputer core, Nelson acts as an integrator for the various shipboard combat systems in a similar concept to today’s AEGIS Combat System, except much faster and with machine-speed environmental adaption.

American relations with China have broken down, resulting in a shooting war in the South China Sea that threatens to spill into the Pacific proper, and eventually reach Hawaii. In an effort to change the dynamic, DDG-1002 forward deploys in stealth to collect intelligence on enemy force disposition and, if the opportunity presents itself, offer a first-strike capability to the U.S. Pacific Command. JOHNSON is spotted by a surface action group of three Chinese destroyers, who take immediate action by firing a salvo of anti-ship cruise missiles followed by surface gunnery fire once in range.

At the voice command of the Tactical Action Officer, Nelson goes to work, taking control of the ship’s self-defense system and prioritizing targets in a similar fashion to Aegis, only much faster, while constantly providing voice feedback on system readiness, target status, and battle damage assessments through the internal battle circuit, essentially acting as a member of the CIC team. Nelson’s adaptability as an AI allows it to evolve its tactical recommendations based on the environment and the sensory input from the ship’s 3D and 2D radars, intelligence feeds, and even the voice reports over the battle circuit. Compiling the tactical picture on a large display in CIC, Nelson simultaneously responds to threats against the ship while providing a fused battle management display to the Captain and Tactical Action Officer. The RIAI does much to lift the fog of war, and automates enough of the ship’s defensive and information-gathering functions to allow the humans to focus on tactically employing the ship to stop the threat rather than reacting to it.

While hyper-convergence, coupled with agile and rapidly-developed software innovation, is the emerging technology, recursively-improving artificial intelligence is the ultimate disruptive technology in the near to medium-term and represents the giant leap forward that many research and development efforts are striving towards. AI has often been relegated to the work of science fiction, and while many futurists see it as the inevitable “singularity” to happen as soon as the mid-21st century, it has not quite gained acceptance in the mainstream technical community. What must be focused on from a warfighter’s perspective is the near-term (within the next 30-50 years) prospects of advances in quantum computing, neural networks, robotics, nanotechnology, and hyper-convergence. These advances could put us on a path towards artificial intelligence within the lifetime of generations currently serving or about to serve in the armed forces.

The debate over whether recursively self-improving artificial intelligence is possible continues,5 with some theorists stating that such an AI cannot be achieved because intelligence could be “upper bounded” in a way that transcends processor speed, available memory, and sensor resolution improvements. Others suggest that intelligence “is the ability to find patterns in data”7 and that, regardless of the more fringe theories surrounding AI, transhumanism, and the ontological discussions of the singularity, “a sub-human level system capable of self-improvement can’t be excluded.”8 It is the sub-human AI, capable of adapting to changing data patterns, that makes a combat system AI an exciting near-future prospect.

Conclusion

This article presented two hypothetical scenarios. In the near-term, a Navy watchstander takes advantage of a hyper-converged infrastructure network environment onboard a U.S. Navy warship to rapidly develop a tactical application to take advantage of disparate databases and cloud data resources, ultimately producing a battle management aid for the ship’s next mission. This scenario took advantage of two emerging technological concepts: hyper-convergence in hardware infrastructure, a reality some major defense acquisition programs such as the Navy’s CANES has already resourced and on-track to field in the coming years, and agile software development in defense acquisition, which is a conceptual framework that must be developed to ensure more rapid and innovative software capabilities are delivered to the force.

The funding for these technological advances must remain stable to deliver HCI to our operating forces as a hardware baseline for future development, and policy makers must continue to find efficiencies in IT acquisition that lead to agile software development to really take advantage of the efficiencies HCI brings. Additionally, DoD IT leaders must think critically and dynamically about how future software updates will be tested and fielded rapidly; our current lengthy testing and evaluation cycle is no longer compatible with either the speed of industry’s vulnerability patching, a fluid content upgrade schedule, or the pace of adversarial threats.

The second scenario describes a near-future incorporation of recursively-improving artificial intelligence within a combat system, which builds upon hyper converged hardware and recursively improving software to deliver a warfighting platform that can defend itself more rapidly and learn from its tactical situation. The simple fact is that technology is changing at a pace no one dared dream as early as 20 years ago, and if we don’t build it, our adversaries will. A recent (2016) article in Reuters, and reported in other media outlets, showcases the People Republic of China’s (PRC) desire to build AI-integrated weapons,9 citing Wang Changqing of China Aerospace and Industry Corp with saying “our future cruise missiles will have a very high level of artificial intelligence and automation.” DoD must adapt its processes to keep pace and remain the world’s leader in incorporating emerging and disruptive technology into its warfighting systems.

Travis Howard is an active duty U.S. Naval Officer assigned to the staff of the Chief of Naval Operations in Washington D.C. He holds advanced degrees and certifications in cybersecurity policy and business administration, and has over 16 years of enlisted and commissioned experience in surface warfare and Navy information systems. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

References

1. Scott Morris. “Putting The ‘Hyper’ Into Convergence.” NetworkWorld Asia 12.2 (2015): 44. 28 Jan 2017.

2. Travis Howard, LT, USN. “’The Next Generation’ of Afloat Networking.” Proceedings Magazine, Mar 2015, Vol. 141/3/1,345

3. Hyperconverged.org. “Ten Things Hyperconverged Can Do For You: Leveraging the Benefits of Hyperconverged Infrastructure.” Retrieved Feb 2 2017, http://www.hyperconverged.org/10-things-hyperconvergence-can-do/

4. Matthew Kennedy & Lt Col Dan Ward. “Inserting Agility In System Development.” Defense Acquisition Research Journal: A Publication Of The Defense Acquisition University 19.3 (2012): 249-264. 4 Feb 2017.

5. Ibid

6. Ibid

7. Roman Yampolskiy. “From Seed AI to Technological Singularity via Recursively Self-Improving Software.” Cornell University Library. arXiv:1502.06512 [cs.AI]. 23 Feb 2015.

8. Ibid

9. Ben Blanchard. “China eyes artificial intelligence for new cruise missiles.” Reuters, World News. 19 Aug 2016, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-defence-missiles-idUSKCN10U0EM

Featured Image: Electronic Warfare Specialist 2nd Class Sarah Lanoo from South Bend, Ind., operates a Naval Tactical Data System (NTDS) console in the Combat Direction Center (CDC) aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln as it conducts combat operations in support of Operation Southern Watch. (U.S. Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate 3rd Class Patricia Totemeier)