By Representative Elaine Luria (D-VA)

Introduction

The Navy recently released its long-awaited 30-year shipbuilding plan, which provided three alternatives for future fleet force structure. The first two alternatives assume “no real budget growth” and “do not procure all platforms at the desired rate.” Good on Navy leadership for acknowledging the elephant in the room — that their plans do not meet desired goals. However, option three, which one assumes is presented as an alternative that will procure platforms at the desired rate, is unrealistic in the Navy’s own words because “industry needs to demonstrate the ability to achieve [this plan].” All three alternatives reduce capability and capacity in the near to mid-term, and introduce unacceptable risk to our ability to counter a rising Chinese threat in the Western Pacific.

I have repeatedly criticized the Navy for not having a strategy and I look forward to hearing how producing three separate shipbuilding plans aligns with their “strategy.” It does not seem to align with former Navy Secretary John Lehman’s idea of the budget process: “first strategy, then requirements, then the POM [Program Objective Memoranda], then budget.” Also, within the shipbuilding plan, the blatant manipulation of how data is displayed masks the true extent of the crisis we are facing in capability and capacity in the coming decade. I will address that here.

Right-Sizing Force Structure for Deterrence

In the 2017 National Defense Authorization Act, Congress codified into law the previous year’s Navy force structure assessment that called for an increase in the size of the fleet from 308 to 355 ships. In the final months of the Trump administration, the Navy released another force structure assessment calling for between 382 and 446 manned ships and an additional 143 to 242 unmanned ships. That assessment, unlike previous years, was driven mostly by then-Secretary of Defense Mark Esper and aligned with the Trump administration’s strategic policy of deterrence by denial as outlined in the 2018 National Security Strategy:

“We must convince adversaries that we can and will defeat them—not just punish them if they attack the United States. We must ensure the ability to deter potential enemies by denial, convincing them that they cannot accomplish objectives through the use of force or other forms of aggression.”

In a denial strategy, a nation seeks to prevent the belligerent from initiating aggression by introducing significant doubt in their mind about whether the ultimate military objective can be achieved. This doubt is based on the threat of overwhelming military force being brought to bear at a time early in the conflict that will make the goals of the aggressor unachievable. A denial strategy requires the will of the defending nation to back up its rhetoric with action when necessary. In advocating for a denial strategy, the Trump administration expressly rejected the alternative, deterrence by punishment. A punishment strategy seeks to deter an aggressor by the threat of pain if they take an aggressive action. But this strategy implies that a nation will not or cannot decisively foreclose objectives to the adversary, and instead hopes that an adversary’s pain threshold can be overwhelmed into submission (an ambiguous proposition). Put simply, denial attempts to prevent the aggressive action from succeeding through instilling doubts about feasibility, while punishment attempts to prevent the action, as the name implies, through the threat of punishment. (Bryan McGrath, managing director of the FerryBridge Group, has an excellent analysis of this in a recent posting.)

In contrast, the Biden administration’s Interim National Security Strategy moves away from both a denial and a punishment strategy, and instead focuses on “Integrated Deterrence” and “Campaigning.” Although these terms have somewhat unclear definitions, they most likely are an outgrowth of an idea telegraphed in a 2020 Foreign Affairs article by the current Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks. In “Getting to Less,” Hicks writes:

“For too long, Washington has had an overly militarized approach to national security. A world in which the United States’ primacy is fading calls for a new approach, especially as authoritarian competitors pursue new strategies to hasten the decline of American power. The time is right, then, for a grand strategy that expands the range of foreign policy tools well beyond what defense spending buys.”

Even before details of the 2022 National Defense Strategy become public, stark differences between the deterrence approaches of the Trump and Biden administrations are reflected in the 2023 budget submission, and are especially clear in the proposed Navy budget. Favored by the Trump administration, a denial strategy is more expensive because it requires more ready, deployed forces, and it may also require the will to potentially use these forces in pre-aggression phases of conflict, where some in the administration and Congress may be unwilling to grant this authority. My impression is that the Biden administration favors a punishment strategy, which is cheaper because it requires fewer forward-deployed forces, thus less force structure, and is more politically palatable because popular support will be more forthcoming after adversaries initiate aggression.

Which strategy is correct? The answer is both, depending on the situation. The problem we face today however is the Biden administration appears to have chosen punishment primarily over denial as evidenced by the two defense budgets submitted from this administration and the recently released 30-year shipbuilding plan. In each, a “divest to invest” strategy has been the overwhelming theme. This divestment strategy gets rid of existing, older (maintenance intensive) platforms and funnels the savings into research and development of high-end platforms that will not be fielded in meaningful numbers for decades. In the ensuing years, the capability and capacity of the current force dwindles, substantially increasing risk in the interim. If the administration were pursuing a denial strategy in concert with punishment, force structure and capability in the near-term would be prioritized over potential future capabilities. This is evidenced across the services, but most explicitly by the Navy. Although obligated by law and its own force structure assessments to grow the fleet, the Navy will instead shrink from 298 ships today to 280 ships in the coming years.

To counter this narrative, the Chief of Naval Operations has shifted from talking about fleet size to talking about capability. “We need a ready, capable, lethal force more than we need a bigger force that’s less ready, less lethal, and less capable,” he recently said at the Navy League’s Sea Air Space Symposium. Specifically, he refers to budget priorities in the bins of readiness first, followed by capability and capacity. To meet the budget topline and maintain readiness while investing in the future, capacity must be reduced. The problem is that by reducing the fleet size we are reducing capability along with capacity. Last year, both the outgoing and incoming Indo-Pacific Commanders testified that China could be prepared to take Taiwan by force in the next six years (i.e., around 2027). Admiral Aquilino went on to say, “We’ve seen things that I don’t think we expected, and that’s why I continue to talk about a sense of urgency. We ought to be prepared today.” The planned reduction in fleet size is not just about loss of capacity, but more importantly, loss of capability in the timeframe Admiral Davidson assessed the threat to be greatest, now known colloquially as the “Davidson Window.”

If China attempts to take Taiwan by force, the defense of Taiwan will be markedly different from what we are observing today in Ukraine. The U.S. and NATO were able to increase and sustain shipments of arms and aid after the conflict started, enabling Ukraine to reverse Russian advances and impose significant costs, both denying the Russians their objectives and making them pay a heavy price. In a China-Taiwan scenario, no such resupply will be possible for an island nation so near to China. Additionally, if the U.S. chooses not to intervene in the direct defense of Taiwan, the human suffering will be considerably worse than in Ukraine, as no viable routes for humanitarian evacuation or aid would exist.

Since being elected in 2018, I have spent much of my time in Congress focusing on the real risk China poses to the U.S. and our allies. That is why I asked the Chief of Staff of the Army, General James McConville, during the Army budget hearing, what winning with China looks like. His response: “Winning with China is not fighting China.” That statement sounds very much like a strategy of deterrence by denial, but for a denial strategy to work, the U.S. must have the capability, the capacity, and the will. The current policy of “strategic ambiguity” opens the possibility that the U.S. will only engage in a punishment strategy if China attempts to take Taiwan by force. But, if China is unsure whether they will be successful because of early and forceful U.S. and allied involvement, then conflict will likely be avoided, or denied. Thus, a denial strategy is the only viable option for the defense of Taiwan.

Reinvigorating Capacity and Capability

In order to use a denial strategy in the case of Taiwan, the U.S. should explicitly express its will by changing the policy of strategic ambiguity to one of strategic clarity, making it clear we will come to the defense of Taiwan, and increase, or at least not shrink, the Navy’s capability and capacity in the near term. One example of this loss of capability is the reduction in the number of MK41 Vertical Launch System (VLS) cells, one of the primary weapon systems aboard guided missile Cruisers (CG) and Destroyers (DDG). The MK 41 VLS can carry a variety of missiles for self-defense and offensive attack for surface, sub-surface, and land targets.

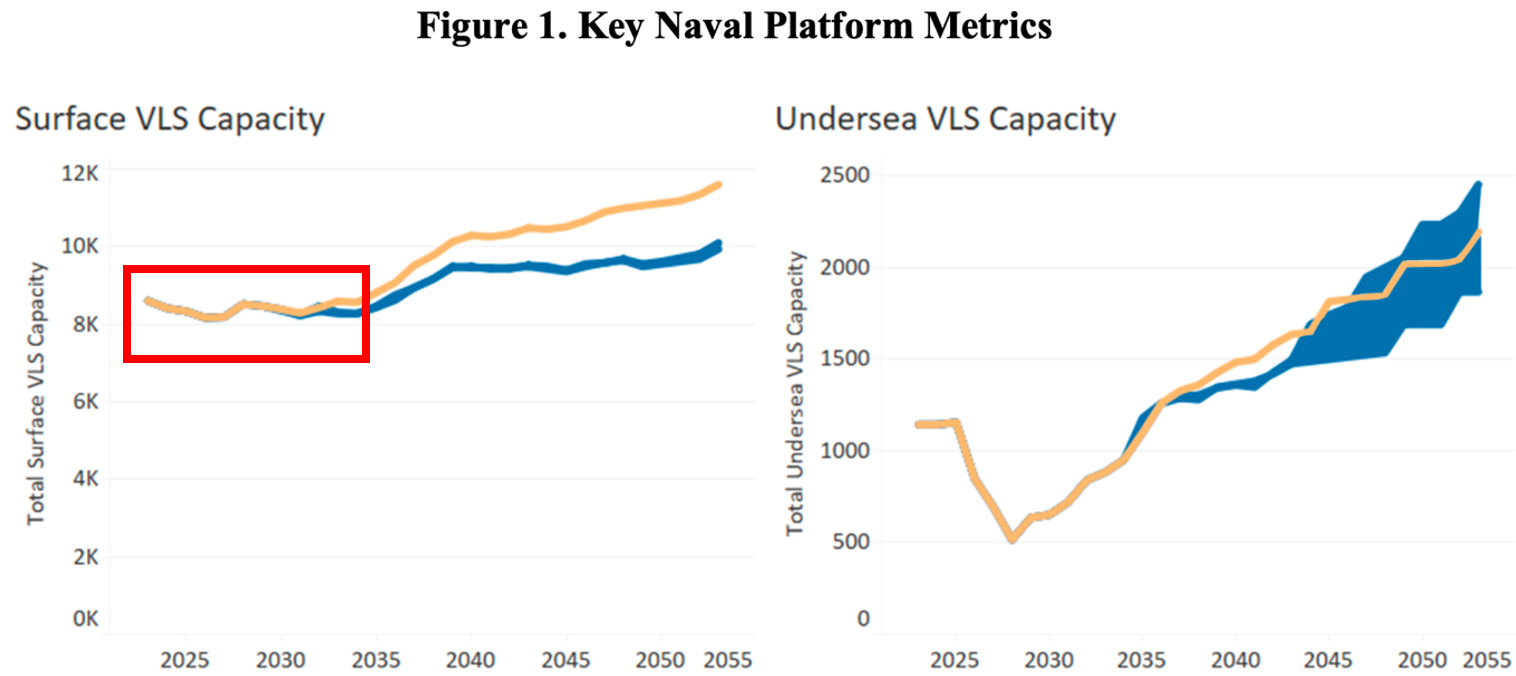

Because of the failures in shipbuilding programs over the past two decades, the Navy has not built replacements for ships that will come to the end of their service lives in the upcoming decade. The result is a distinct fleet-wide drop in missile capacity. The construction of the new guided missile frigate with only 32 VLS cells, or submarines with the Virginia Payload Module, will do little to stem this steep reduction. However, in its 30-year shipbuilding plan, the Navy displayed the VLS data such that it appears there is no reduction in the near-term and that it will experience growth in the long-term as displayed in the graphic below (red area highlighted for emphasis and discussed below):

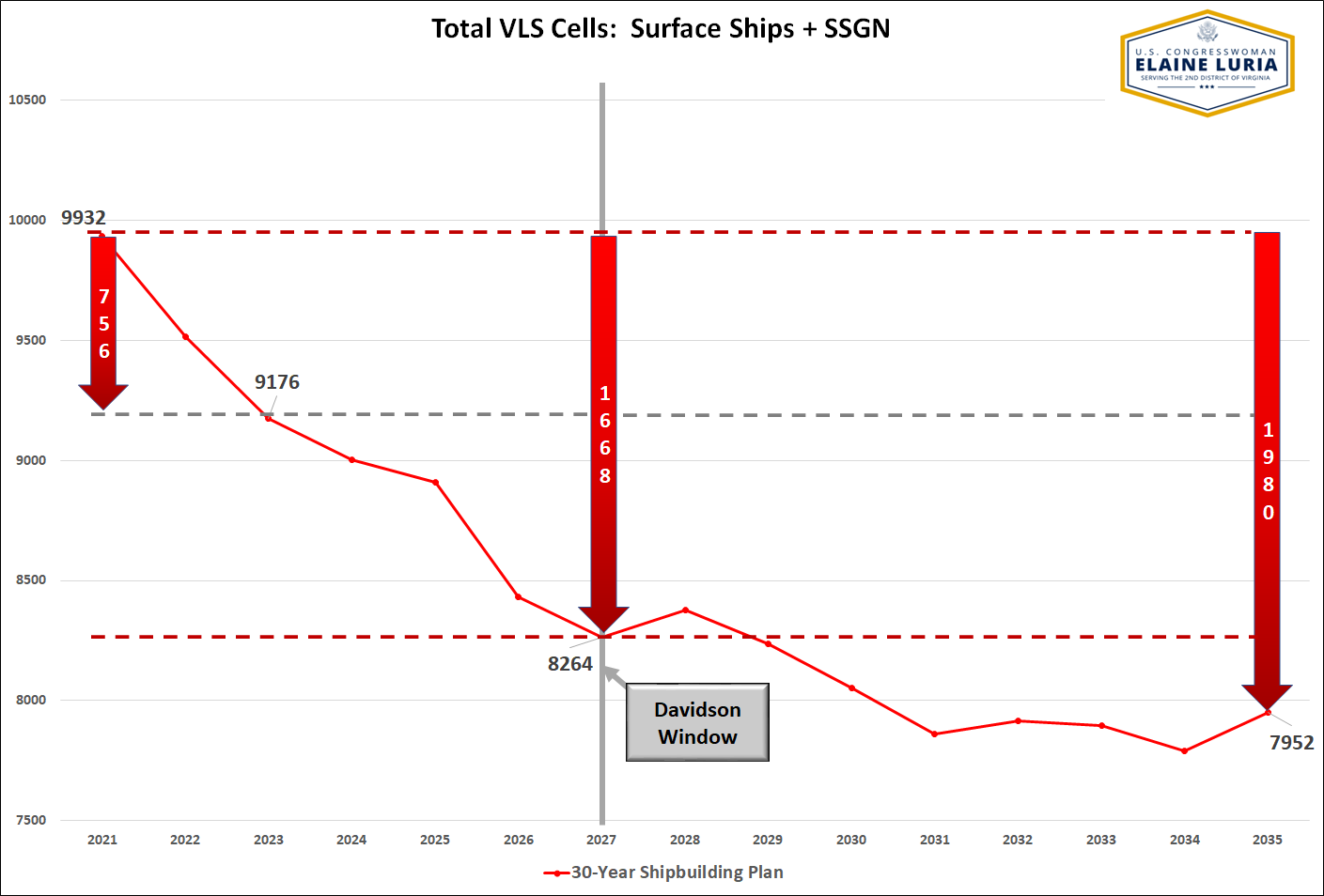

By using a 0-12K scale, starting in 2025, expanding the time horizon, and separating surface and sub-surface VLS cells, it masks the true loss of VLS capability and capacity in the “Davidson Window.” I took the same data, combined surface ship and guided-missile submarines (SSGN), and narrowed the timeframe to 2021-2035, which is the critical window for potential Chinese action against Taiwan. The resulting visual is quite different than what the Navy produced.

The current budget proposal to decommission five cruisers, along with last year’s budget proposal to decommission seven cruisers, will result in a loss of 756 VLS cells by the end of 2023. In the 2021-2027 timeframe, the “Davidson Window,” the Navy will lose 1,668 VLS cells and 1,980 cells by 2035 even while building the Constellation-class frigates and additional DDGs. For comparison, all European NATO countries combined have 2,394 VLS cells. If Admirals Davidson and Aquilino are correct about the near-term risk, reducing capacity makes a denial strategy impossible and reducing capability makes a punishment strategy hardly credible.

Last year, Congress stepped in to provide an additional $29 billion over the requested defense budget and forced the Navy to retain several cruisers and build additional DDGs. Adding additional force structure and appropriations is important, but comes at additional cost for manning and maintenance in later years. To counter the downward trend in VLS cells, several options are feasible with a modest increase in the Navy budget or by reducing spending on unmanned surface vessels. The following suggestions are not meant to be prescriptive, but instead are the kind of solutions I would like to see presented to Congress alongside their budget. By their current plan to reduce capability and capacity in the next decade, the Navy is accepting undue risk if conflict with China does occur over Taiwan.

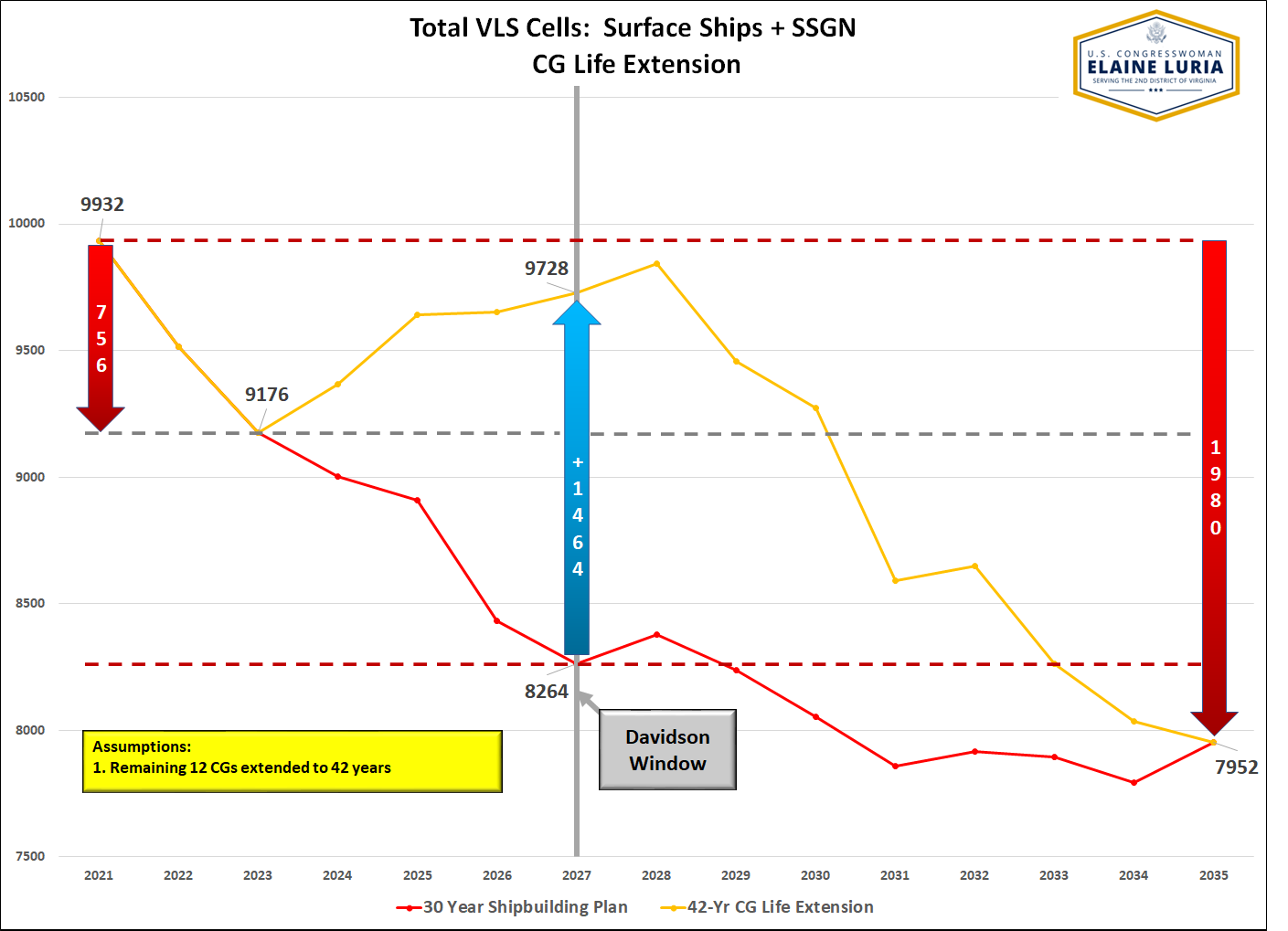

Several options are readily available to prevent the catastrophic loss of VLS cells. First, if the Navy decreases to 12 Cruisers in FY 23 but retains these 12 for a 42-year life, VLS inventory will be reduced only slightly in the Davidson Window, but still fall by 1,980 cells in 2035 as shown in Figure 3. Considering the billions of dollars already spent on upgrading and modernizing cruisers in the last decade, this would seem to just be good stewardship of taxpayer dollars.

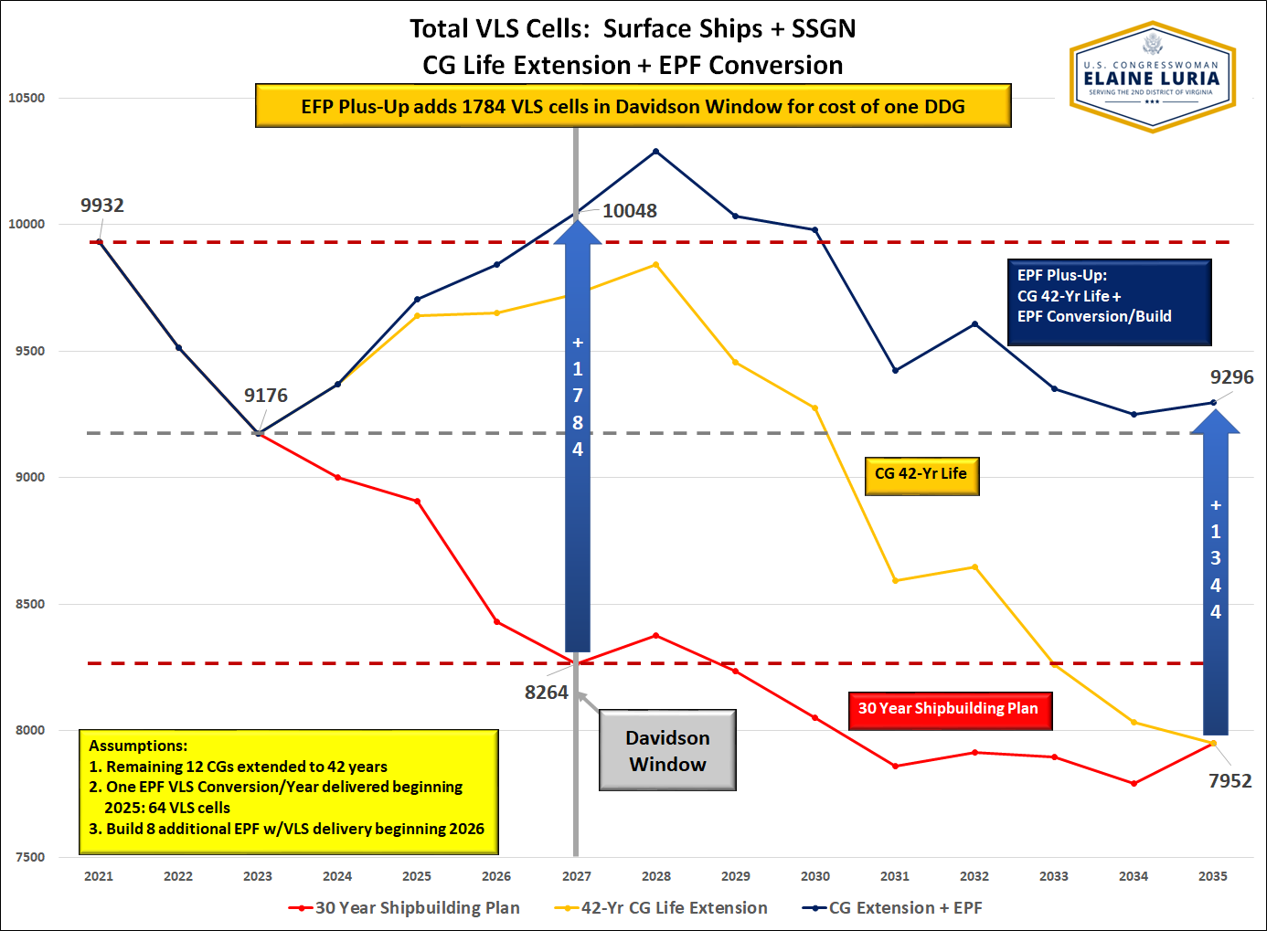

A second option to significantly decrease risk in the near to mid-term is to convert 13 of the existing Expeditionary Fast Transport (EPF) ships to be VLS capable with a 64-cell capacity and build eight additional ships. Because the EPFs are crewed by Military Sealift Command (MSC) civilian mariners, they operate at a fraction of the cost of the nine Littoral Combat Ships that the Navy proposes to decommission this year. Additionally, the ships are available for deployment at a higher rate than other Navy ships and their funding profile can be scaled to match need. An additional eight VLS-capable EPFs could be built and operated for the cost of around one new DDG. Further, as examples of distributed and low-cost arsenal ships, these EPFs can be a reasonable incremental step toward providing an autonomous capability in the 2040s. This modest investment would increase the number of VLS cells above 2021 levels within the Davidson Window and maintain a reasonable capacity through 2035 as shown in Figure 4:

There are legal implications to consider in using civilian mariners to operate offensive-capable ships, just as there are legal implications to using unmanned arsenal ships, however, with a dedicated military detachment and designation as a United States Ship (USS) versus United States Naval Ship (USNS), these obstacles can be overcome. Known hull cracking problems on the EPF must be addressed, but for the cost of building one Flight III DDG, the Navy can build eight additional EPFs, and because the ship is operated by MSC, can operate 14 EPFs for less than the cost to operate one DDG annually.

Conclusion

The Navy fiscal year 2023 budget calls for building eight ships, while decommissioning 24, reducing the fleet size to 280 ships within the Davidson Window. In addition to reducing capacity, the budget reduces capability and introduces unacceptable risk in the Indo-Pacific theater of operations to deny China a fait accompli over Taiwan. The Trump administration’s 2018 National Security Strategy correctly identified the faulty thinking now being repeated in the Biden administration’s two most recent defense budgets:

“We also incorrectly believed that technology could compensate for our reduced capacity—for the ability to field enough forces to prevail militarily, consolidate our gains, and achieve our desired political ends. We convinced ourselves that all wars would be fought and won quickly, from stand-off distances and with minimal casualties.”

I have proposed two modestly priced alternatives to provide additional VLS capacity in the near-term during the vulnerable “Davidson Window.” Each year the Navy continues down a path of divest-to-invest, resulting in unacceptable reductions in capacity and capability when we need them most—all in the hope of fielding new capabilities that will level the playing field with our adversaries in the far distant future.

One key element not fully explored in this article is the latent capability that VLS cells offer is dependent upon what payloads fill their magazines. The U.S. Navy is suffering a clear disadvantage in anti-ship weapons with respect to China, which is fielding supersonic anti-ship weapons across its surface forces, bombers, land-based forces, and undersea forces in high numbers. By comparison, almost all the anti-ship capability of the U.S. armed forces resides in a limited number of surface and air-launched Harpoon missiles, whose fundamental design is 45 years old. The surface fleet’s launch cells are mostly filled with defensive anti-air weapons, but newer weapons such as Naval Strike Missile, Long-Range Anti-Surface Missiles, Maritime Strike Tomahawks (MST), and SM-6 missiles, if procured in higher numbers in the near-term, could close the ASCM gap that currently exists between the PLA(N) and U.S. Navy. However, the budget submission of the Navy across the Future Years Defense Program (FYDP) does not buy these weapons in sufficient numbers to close the anti-surface weapon gap. The Air Force, for its joint contribution, appears uninterested in procuring enough LRASMs for the B-1 bomber fleet and is instead developing other capabilities such as QUICKSINK. The bottom line – even if the U.S. Navy has a strong advantage in VLS cells, it will hardly be able to punish or deny adversaries in a maritime conflict if those cells barely hold any anti-ship weapons.

The 355-ship Navy appears to be a pipe dream, as fleet size has not surpassed 300 ships since 2002 in the Bush administration. I propose a way to stop the Navy’s hemorrhaging at an acceptable cost. But what I would prefer most is for the Navy to develop appropriate triage measures itself instead of relying on the Congressional emergency room every year.

Congresswoman Elaine Luria represents Coastal Virginia, home to the world’s largest naval base. Before running for Congress, Elaine served two decades in the U.S. Navy, retiring at the rank of Commander. A Surface Warfare Officer who operated nuclear reactors, she was one of the first women in the Navy’s nuclear power program and among the first women to serve the entirety of her career on combatant ships. Of all members in the House Democratic Caucus, she served the longest on active duty, commanding hundreds of sailors and deploying six times to conduct operations in the Middle East and Western Pacific. Congresswoman Luria is the Vice Chair of the House Armed Services Committee and serves on the Veterans Affairs and Homeland Security Committees as well.

Featured Image: STRAIT OF GIBRALTAR (March 31, 2015) The Ticonderoga-class guided-missile cruiser USS Vicksburg (CG 69) transits the Strait of Gibraltar as part of the Theodore Roosevelt Carrier Strike Group. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist Seaman Anna Van Nuys/Released)

Well…it is clear, Representative Luria is the “Carl Vinson” advocate the Navy needs in Congress for the 21st Century.

JohnT. Kuehn

CDR USN (retired)

If they are going to decommission EPFs, then convert them to this new role instead. Otherwise, just start with a new hull. Keep the engines, waterjets and transmission and other interchangaeble gear..

I expect it would be faster to modify an existing hull than build a new one. That the EPFs are very loud underwater, have a 1200nm range and it isn’t clear how well they would do in the Pacific far from shore could be issues.

A number of us have advocated building cheaper ships armed with offensive anti-ship missiles for at least the last decade, and have been resolutely ignored by the Navy. I can only hope Rep. Luria’s voice breaks through the wall of denial and inertia the Navy has erected.

After decades of wasted money and opportunity the US is falling behind the PLA. All the stumbling bumbling blundering of years when something could have been done are gone forever. This article cries out with desperation tomorrows will be filled with panic. The US is in deep trouble.

Regarding VLS: certainly putting VLS on cheaper ships like EPF is way better than nothing, VLS does impose some limitations because it cannot be reloaded at sea. Plus, the table on total VLS cells is a little misleading because that is a Navy total and does not reveal how many are available in Westpac, say. Beyond that, most cells are loaded with defensive missiles. Some cells may be empty due to lack of missile inventory, not to mention those cells on ships in maintenance. A VLS-based distributed force, say a flotilla of killer EPFs packing offensive missiles, would have to have some regional safe port to reload in and a rotating scheme of ships forward. The alternative is to put missiles in containers and replace them on board with, say, V-22s, so the ships can remain on station. In any case, the graph of total VLS cells does not tell the whole story.

IT’s doable but its a paradigm shift on operations. MSC has a long history of Hybrid crews. Spearhead in the early days of its deployments would be the closest model for routine annual funding required a serious comparison. The the platform with a mission package is indifferent to who operates & tends it. So it comes down to how your going to man it that satisfies a peace time and a war time manning mix that complies with the established laws. normal ops: A mixed crew using the MSC crew on an EPF in a care taker roll with a core AD Navy crew minimum, to include command and continuous security for the weapons system when not in an escalated conflict. AS the threat shifts at a certain point. You could replace the 24-30 Civmars with an AD Navy/ Marine(?) trained and certified detachment of the same or even double (with adjusted berthing) That would absolve the conflict of interest under the law of war. So what to do with the AD units until needed? triple or quad up detachment increments of the Missile EPF fleet on 1 EPF as their continuous routine trainer, until needed to disperse to their war time assigned ship. That would also justify a core of IDC’s and culinary staff to deploy with each dedicated ship detachment. Because EPF’s DON’T have a Doc; just like your commercial ships don’t. Its one of the deck officers as MED PiC . Just a spitball thought folks.

thank god someone is calling out the total BS that the Navy has become in not addressing the big problem they have, simply put, not enough ships, and not extending the lives of those they do have, not taking advantage of current ships for modification to help in this, and not building enough afterwards and the shipyards basically not investing enough in themselves and short of the government paying them, it’s status quo (if wrong, I’ll apologize). Some ideas that they could use

-the fast transports are a great idea, though range is an issue. I’d think they should take these though and scrap the whole Marines getting LST’s again. Find a way to offload vehicles from them on a beach environment, and there’s your ship.

-there have been multiple ships of huge size put on the retirement scrap list. As we know, once it’s mothballed, it’s dead, right or wrong. But if you want to fix VLS shortages, take a Tarawa class and use all that hangar space for VLS launchers. Talk about a huge new load. When they were retired, they were all in good shape, in fact there was talk of selling them. Here’s a great use for them.

-spare the ballistic missile defense duties of cruiser/destroyer where you can. If it’s to stop a rogue ICBM or three, convert an older ship that can take targeting cues from another set of sensors rather than a gigantic array built on a huge ship. Hell, a mothballed oliver hazzard class, modified, to handle the larger SM class of missile to shoot off two at a time would be enough to sit off the coast of say North Korea. No need to waste a Burke if that is the main reason. Either way, these assets are paid for and networking is now available to not force the platform to be a do it everything platform