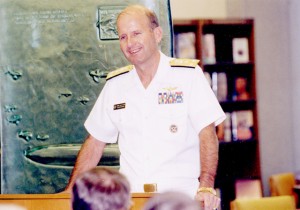

You could hear a pin drop in the room. Retired Vice Admiral John Ryan, U.S. Navy, had the group of 35 midshipmen captivated as he recalled a remarkable young woman he’d met. She had been born without arms and legs, but she took her mother’s advice to focus on what one can do instead of what one can’t. This woman managed to become an engineer for NASA. The moral of Admiral Ryan’s story was to always examine other people’s lives and consider how they can shape the way we lead ours.

This was just one of the many lessons I took from the former Naval Academy Superintendent and current president of the non-profit Center for Creative Leadership (CCL). He spent the day visiting the Boston University School of Management and made time to address NROTC midshipmen.

What is striking about Admiral Ryan is his approach. His background commands great respect – in addition to his naval service, he oversaw 80,000 faculty and staff as Chancellor of the State University of New York – yet the soft-spoken former P-3 pilot also presents authenticity and humility. Perhaps that’s what makes his wisdom stick.

“You have to be comfortable being uncomfortable,” Ryan said in describing the “learning agility” that distinguishes great leaders. He and his organization, CCL, have found that continually embracing challenge and having a “growth mindset” are essential to leadership success. Great leaders are able to learn from experiences and apply them to new ones. They also need to make their subordinates feel comfortable in “stretch assignments” and willing to take chances. This takes sincere mentorship and a culture that forgives occasional failure.

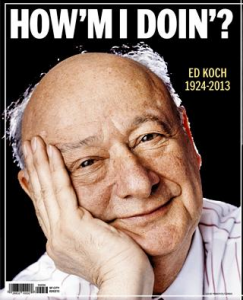

The other theme Admiral Ryan stressed was self-awareness. He jokingly recalled the late New York City Mayor Ed Koch who would famously ask citizens “How’m I doing?” Leaders need to open themselves up to feedback, be willing to hear the bad in addition to the good, and make time to reflect.

When was the last time you heard a naval leader encourage officers taking time to reflect and learn from their everyday leadership experiences? Yet as Admiral Ryan explained, this is essential to growth and self-awareness.

The U.S. Navy, by necessity, emphasizes technical and tactical proficiency, but through my MBA classes and now Admiral Ryan’s insights, the importance of “softer skills” is becoming increasingly clear. Vice Admiral John Ryan may no longer wear the uniform, but the Navy and our officers could learn a great deal from his lessons, as I myself was fortunate to do today.

LT Chris Peters is a surface warfare officer in the U.S. Navy and an instructor at Boston University.

The opinions and views expressed in this post are his alone and are presented in his personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy.