The following article is special to our International Maritime Shipping Week. While we often discuss the threats to maritime shipping, this week looks at dangers arising from such global trade, and possible mitigations.

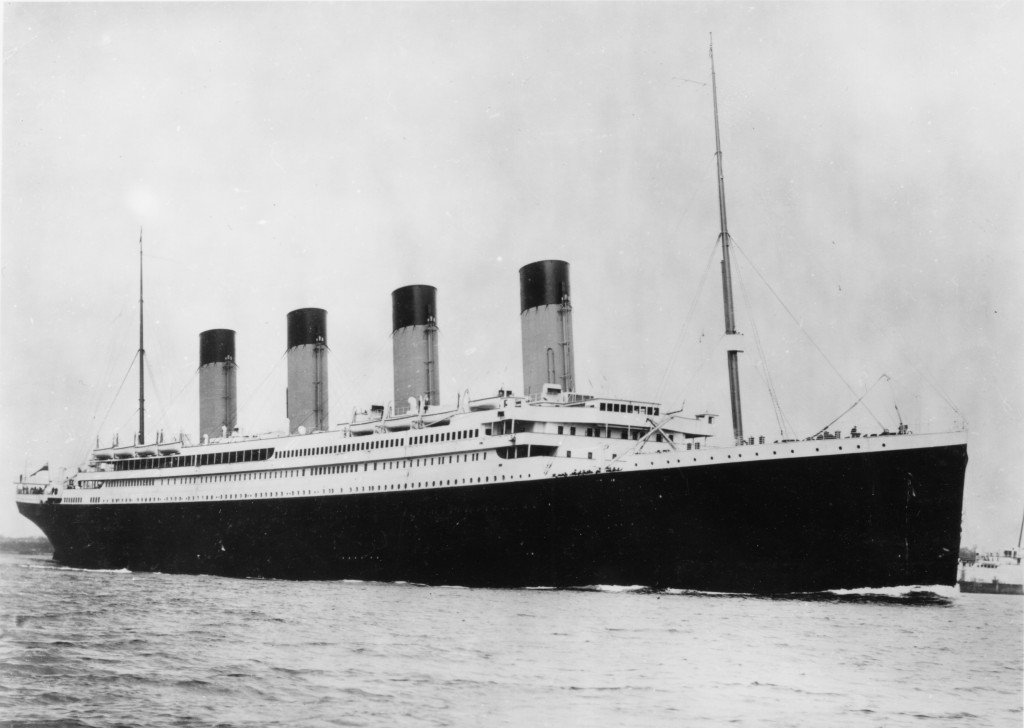

Sometime in 1843 or 1844, a ship most likely from Baltimore, New York, or Philadelphia landed in a European port. Among the seed potatoes in its hold was the North American fungus Phytophthora infestans. The resulting potato blight swept across Europe, and when it combined with the abominable agricultural policy in Ireland, the outcome was nearly a million dead and a 25 percent reduction in population if including emigration.

Last year, around 25 million food shipments entered the United States, primarily by sea, but only roughly two percent of them were inspected by Food and Drug Administration agents, and nearly all of these inspections occurred on U.S. soil (the largest share at the massive port of Los Angeles). Meanwhile a 2012 report by the Centers for Disease Control shows that from 2005 – 2010 at least “39 outbreaks and 2,348 illnesses were linked to imported food from 15 countries”, and that “nearly half (17) occurred in 2009 and 2010.”

The fact is, importing foods to the United States is not only big business, it’s risky business. Food imports almost doubled from 1998 to 2007, with much of the growth in fruit, vegetables, and seafood; and agricultural inspections have struggled to keep up. While the Food Safety Modernization Act passed by Congress in 2010 allowed for the implementation of the computerized Predictive Risk-based Evaluation for Dynamic Import Compliance Targeting (PREDICT) system, a human inspection is still required to render a verdict.

But there’s more. The introduction of blight or disease into the food supply of the United States would be a major long-term success for an adversary. That’s right, agro-terrorism is real and you should be worried about it. A subset of bioterrorism, agro-terrorism is the introduction of an animal or plant disease with the purpose of causing economic, health, and social damage. The seemingly low shock value of the topic means less public attention, but it is real enough that former Secretary of Health and Human Services Tommy Thompson gave a warning speech on its dangers—and was eviscerated for calling attention to the risk for adversaries.

The problem is that the United States’ food supply really is vulnerable to agro-terrorism. In terms of targets, the agricultural sector is an easy mark due to modern livestock-raising methods; their feed preparation and distribution process; the geographically dispersed location of farms and ranches; and the relative safety of handling animal and plant pathogens by a human.

The low inspection-rate of imports coming by sea, and relatively smaller dollar amounts going to security for those imports, provide perhaps the safest vector for the undetected transmission of a pathogen. An adversary could rely on blind luck, transporting tainted food and hoping that it is added to a distribution system to achieve limited results. But an organized network could be more deadly by using existing sea routes for transport of contraband to smuggle pathogens to a recipient within the United States for more targeted distribution. Just as trafficked drugs or persons slip past the low inspection capacity of Customs and Border Patrol, pathogens infecting food could land in the hands of a determined adversary.

What would the effects be of such a pathogen? Economically, the calculation is complicated. The 2001 foot-and-mouth outbreak in the United Kingdom, probably caused by the illegal import of tainted meat that was subsequently fed to pigs, is estimated to have cost that government $13 billion, including second-order impacts to businesses and restaurants dependent on the sale of livestock. But this figure does not include the cost of lost exports from the meat embargo immediately imposed by Britain’s trading partners.

In the United States, where the CIA World Factbook estimates the agriculture sector makes up $172 billion of the nation’s 2012 GDP compared to the United Kingdom’s $17 billion, the second and third order effects would be even greater. A 2002 limited study by National Defense University estimated that an outbreak of foot and mouth disease restricted to only ten ranches in the United States would cost up to $2 billion in cascading effects. A widespread outbreak would be orders of magnitude greater.

The health effects for citizens are more obvious, if only because of the legend of the Irish Potato Famine in the mythos of America’s development. But as with all forms of terrorism, a small death toll is all that’s needed to cause widespread panic. A 2005 outbreak of E. coli related to bagged spinach killed but three and sickened about 250, yet spread fear (and excuses for subbing fries for salad) across the country. If such as scenario was followed by a public statement from the responsible party, with promises of additional attacks, the response could collapse confidence in the entire food system, resulting in wide-spread loss of jobs and cascading social unrest.

So what’s an American to do? The short answer is “not much.” The sheer volume of transported goods, the importance of the human element to detect agriculture disease, and the necessarily quick transfer of perishable items make stopping agro-terrorism before it occurs a near impossibility. Like many other forms of asymmetric attack, a determined adversary will succeed.

One thing that can be done is preparation to mitigate the effects of such an attack. The long-delayed National Bio and Agro-defense Facility (NBAF) took another lurching step forward in the FY14 Homeland Security Appropriations Bill in both the House and Senate. Designed to be one of the most sophisticated laboratories in the world, it would study the most dangerous pathogens in hopes of finding antibiotics or resistants to limit the damage an outbreak could cause.

Multiple Homeland Security Presidential Directives also require Federal and local coordination preparations and plans to respond to an agro-terror attack. In most cases, mitigating the effects of such an attack will require identifying the pathogen, containing it, and then taking steps to destroy it before it can escape from the containment zone. These steps can only be taken in time with prior coordination and practice.

Finally, we need to do what the Irish couldn’t—be able to quickly tell which ship, at which port, and from which point of departure carried the blight. While impossible to inspect every cargo container, with a concerted effort the United States can establish a system that provides more efficient and effective tracking of the containers themselves over the course of their travels, from loading to unloading. Shedding more light on their journey creates a less-hospitable route for potential practitioners of malfeasance.

Sherman Patrick is a Senate staffer working on national security issues. The views expressed in this article are his alone.