With a rush of wind and the deafening sound of rotor blades cutting through the humid Philippine air, U.S. Navy and Marine Corps helicopter and V-22 crews are delivering lifesaving aid to remote villages in the Philippines following the devastating Typhoon Haiyan. This does not happen by accident. The U.S. ability to project humanitarian assistance/disaster response (HA/DR) efforts across the globe is a direct result of investments in capabilities and platforms as well as in personnel and forward posture. So what are material capabilities are most useful in disaster response, what are the “X” factors, and which U.S. surface ships platforms deliver those capabilities best (for the best cost)?

The 10 Material Capabilities Essential to Conduct HA/DR:

1 – Helicopter/Vertical Lift Capacity: Operating from naval forces stationed off the coast, a helicopter’s low footprint and vertical take-off and landing makes it a palatable option for delivering aid and conducting search and rescue in almost any circumstance, especially where infrastructure has been negatively affected and disaster damage extends into the interior of the country. Helicopters/vertical lift assets enable relief organizations to centralize relief supply stockpiles in airports capable of landing larger cargo planes, and the Navy and Marine Corps helicopters and V-22s are then able to ferry those supplies to remote and inaccessible areas. Likewise, helicopters can transfer needed supplies (including water) directly off ships stationed off the coast to areas on land.

2 – Small Boats/Landing Craft: Particularly useful in HA/DR situations where port facilities have been damaged (or nonexistent), with the majority of the damage on the coast. Landing craft (LCACs, LCUs) can transfer heavy supplies and equipment (bulldozers, trucks, etc.) quickly and without requiring port facilities.

3 – Medical Facilities: Onboard ship facilities or the ability to provide medical personnel and treatment ashore becomes critical in the initial response for traumatic injuries as well as in subsequent days when infections and diseases spread by unsanitary conditions in the wake of the disaster.

4 – Cargo Handling: Ships capable of quickly loading and offloading supplies play an important role. Several ships have unique capabilities (cranes, roll-on/roll-off, etc.) to load and offload supplies in port, provided port facilities are still functioning in the disaster area.

5 – Humanitarian Supplies: Supplies provided a lifeline in the initial and follow-on phases of the HA/DR response. Tents, plastic tarps, portable RO units, food, blankets, etc. can be stored on ships or loaded in port for transfer to the HA/DR area.

6 – Shipboard Potable Water (H2O): Ships make fresh, potable water from seawater using a variety of methods including reverse osmosis (RO) and evaporation. Producing fresh water at sea is important to relief efforts as access to safe drinking water is always one of the biggest issues facing the disaster struck population ashore. Bottled water is expensive to store and transport into the area, so being able to bottle the ship’s potable water and transfer it to shore via air or landing craft saves time, money, and often showcases the ingenuity and innovation within a ship’s crew.

7 – Speed to Station: All the supplies, personnel, and equipment are useless unless the Navy can get them on station quickly. Natural disasters can occur with little advance notice and cause extensive damage quickly over a broad area. Quick response times prove critical as the first few days of a disaster are crucial to locate survivors (search and rescue), treat the seriously wounded, and provide critical supplies to isolated populations before infrastructure is restored.

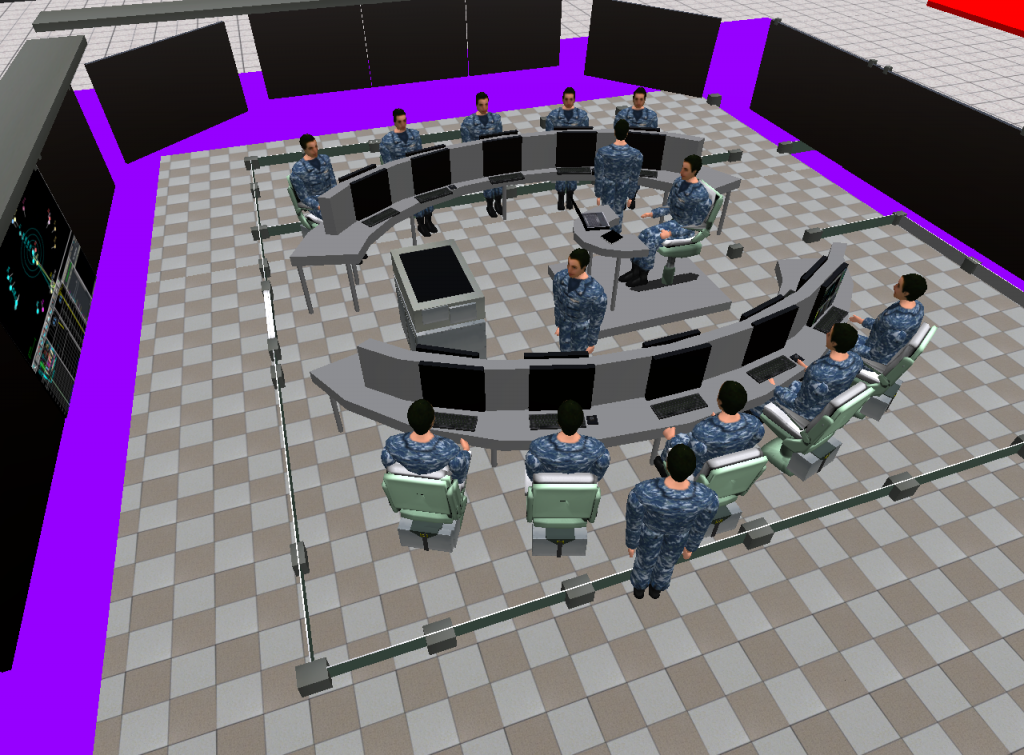

8 – Command and Control (C2): Communications enable ships to relay information to the Joint Task Force Commander (should one be appointed), Combatant Commander, relief organizations (USAID and non-governmental organizations (NGOs)), other ships, aircraft, and diplomats ashore in order to de-conflict potential issues and efficiently distribute aid.

9 – Surge Berthing: The ability to house additional people onboard a surface ship certainly to support HA/DR efforts. In some cases this might mean hosting non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or other U.S. government organizations like USAID. Berthing can also be useful to house host nation and coalition liaisons, rescued locals, and joint task force personnel should a joint force be set up.

10 – Draft: Disasters typically negatively affect port facilities and transit capabilities on land, so ships with the ability of getting closer to land cut down transit time (and turnaround time) for helicopters, small boats, and landing craft coming from sea-to-shore and vice versa. A shallow draft typically enables ships to operate closer to shore.

*One important note on capabilities, local politics, and sensitivities must always factor into decisions on the extent and types of capabilities to use. For example, in some cases, the Navy might have a fantastic ship-to-shore supply transfer capability using LCAC’s and landing craft, but the optics of the U.S. “assaulting” the beach might not play well in certain circumstances – so commanders must be cognizant of the cultural conditions and public perception.

The “X” Factors:

Of course, all that material capability to do HA/DR would be fairly useless without the U.S. Navy’s advantages of forward deployment, extensive training, and skilled personnel.

Being there counts. Forward deployments and overseas stationing has meant the difference in many HA/DR missions because the U.S. has been able to respond quickly and with a credible capability shortly after a disaster strikes.

Being trained counts. An around the clock operations tempo (optempo) for most major HA/DR missions stresses a crew’s training to the limit – this where the “readiness” that the Navy’s expensive yet effective training pipeline and the Navy’s considerable operations and maintenance budget expenditures shine through.

Being motivated counts. Sailors and Marines have demonstrated a remarkable operational agility, creativity, and mission dedication in HA/DR events. Perhaps this has been the ultimate “X” factor in HA/DR events. Their ability to respond quickly, act cooperatively and professionally, and demonstrate a genuine humanity and kindness for those in need – you just can’t create that in a Navy and Marine Corps overnight.

The Best Platforms:

So, given the Top 10 Material Capabilities and the “X” factors, which platforms give commanders the best “bang” and “bang for the buck” in HA/DR operations?

1 – Big Deck Amphib (LHD/LHA): Several factors make the LHD the best platform – large organic helicopter/vertical-lift capacity (with deck space enabling simultaneous refueling and reloading for multiple aircraft), surge berthing, medical facilities, and a shallower draft. However, the big difference between the LHD and the #2 (the aircraft carrier) is the well deck with associated landing craft, LCACs/LCUs, and embarked Marines and Marine equipment. These factors enable LHDs to perform heavy lifts from ship-to-shore and vice-versa that the carrier simply cannot deliver. Essentially, LHDs were designed to support amphibious/expeditionary operations so supporting HA/DR ashore is embedded in the platform’s DNA. LHDs bring capabilities to deliver supplies and aid, much like it delivers Marines ashore. When you factor in cost of the platform (~$3B a ship), the LHD also provides the most “bang for the buck” for a HA/DR situation.

2 – The Aircraft Carrier (CVN). A close second, the carrier has significant capabilities to support HA/DR, especially if it embarks a full complement of helicopters and flies off most of the fixed-wing jets. Its large deck space, speed to station, medical facilities, fresh water generation, C2 suite, and berthing space make it a formidable HA/DR asset. From a public outreach/optics perspective, one cannot deny the soft/smart power appeal of sending an “aircraft carrier.” The public perceives that CVN’s have become the symbol of U.S. seriousness in many cases. The generally more capable (and less expensive) “helicopter carriers”/LHDs just do not carry the same cachet in international media and political circles. From a cost perspective, however, the CVN costs about $5B to buy and the new Ford-class costs well over $10B. Unlike the LHD, the CVN was designed for strike aircraft sorties and projecting power with fixed wing aircraft – not expeditionary missions. It is a testament to the CVN crews how well they have adjusted on the fly to a helicopter/vertical lift mission during a HA/DR operation. In the end, the carrier is an incredibly valuable asset to use for HA/DR from a public relations and capability standpoint.

3 – The Other Amphibs (LPD/LSD): With reduced helicopter capability due to smaller deck space and housing, the LPD comes in lower than the flattops in overall HA/DR capability, but still provides a powerful asset to any HA/DR mission. The LPDs ability to load and off load supplies in port easily enables it to gather critical supplies before getting underway to a disaster response. Like the LHDs, LPDs also have large well decks from which to sortie LCACs and LCUs for ship to shore transfers of heavy equipment. LPDs also have a shallow draft, medical capabilities, and ability to store humanitarian supplies. However, its speed to station factors negatively against the platform. Yet, LPDs provide considerable HA/DR capability for relatively low cost (a little under $2B).

4 – JHSV: Speed, low draft, loads of berthing, and supplies-storage capability make JHSV a contender in HA/DR response. With a few modifications to the new platforms, JHSV could be a very low cost (only $200-300M a copy), and high capability asset for use in future HA/DR situations. If you combined several JHSVs together in a HA/DR “wolf pack” you could perhaps take care of the majority of disaster response events without having to call on the larger, capital ships.

5 – Hospital Ships: Like the carrier, the media attention the U.S. gets for deploying one of its two USNS hospital ships is considerable. The medical facilities and ability to be a game changer in HA/DR situations is unquestioned, but they are hampered by slow speed to station, deep draft, and lower helicopter capacity. However, their slow speed to station is the ship’s largest hindrance, meaning by the time they arrive on station for a natural disaster outside of the Western Hemisphere, their most unique function (high end trauma operating rooms) are not as in demand. The symbolism, however, can be a powerful signal and make hospital ships a key element in HA/DR events, especially in regions with limited health infrastructure.

6 – Supply Ships: The backbone of any HA/DR operation, USNS ships provide massive stores, supplies, fuel, and water to sustain the HA/DR response, as well as an ability to support the effort using the USNS’s organic boats and helicopters. They are essential to establishing and sustaining the sea base of operations during the HA/DR response, yet usually do not provide support without another surface platform working in concert.

7 – Cruisers/Destroyers (CG, DDG) and Littoral Combat Ships (LCSs): The least capable platforms (material-wise), they score lowest in the top 10 HA/DR capabilities and are relatively costly to acquire. Yet, they serve a valuable presence function, and can act as a “lily pad” for refueling helicopters operating off the larger surface platforms (or their own organic helicopters) – serving as a range extender for those invaluable relief and search and rescue flights.

Key Takeaways

The most cost-effective (as far as platform procurement goes) and highest capability HA/DR response group would be a LHD and LPD in combination with a USNS supply ship. However, time counts and perceptions matter, so one can bet on continued use of CVNs and cruisers/destroyers as the “first responders” by Combatant Commands if they are available and closer to the scene. Certainly one sees this in the latest Typhoon Haiyan response where the initial George Washington battle group sortied first, subsequently followed by amphib deployments from Japan.

The future is in the JHSV, Afloat Forward Staging Bases (AFSB), and Mobile Landing Platform (MLP). This group of lower cost platforms can cover most of the stability and disaster response missions. From Theatre Security Cooperation to HA/DR, having these platforms forward deployed with significant humanitarian supplies, surge berthing capacity, and ability to surge helicopter and land craft dets aboard will enable the United States to potentially contribute to HA/DR missions without pulling capital ships off station.

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the HA/DR Mission. Over the last two years, with the increased budget uncertainty, HA/DR was not mentioned as much in naval circles in favor of more “warfighting-centric” missions. Yet, the Navy still holds HA/DR as a “Core Capability” in their 2007 Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower and in the Naval Operations Concept 2010. While HA/DR has had its share of detractors, the reality remains that naval forces will continue to perform HA/DR missions. The positive public perception of the Navy’s role in HA/DR, civilian leadership’s desire to “do something” in the face of suffering, and the very real potential geopolitical gains will continually translate into HA/DR missions for Navy. In fact, from the Indonesian tsunami in 2004 to the Japanese tsunami response in 2011, the U.S. Navy averaged over 1.5 major “reactive HA/DR” missions per year. Perhaps, not coincidentally, the Navy’s slogan became “A Global Force for Good” during that same time period. The Navy bought into HA/DR by being good at it, and the demand signal from home and abroad will continue to spike when disaster strikes; simply put, the international community and American public now assume the U.S. Navy will be en route shortly. Perhaps more importantly these days, the Navy’s timely and very public involvement in HA/DR missions can help bolster the Navy Department’s case to secure funding within the Pentagon as the nation’s forward deployed, ready response force.

Navy leadership should embrace HA/DR and use it as a real way to explain the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps’ “value proposition” to DoD and to the American public in the looming sequestration budget battles. The public does not necessarily understand what Navy ships do at sea and/or even understand why they are at sea in the first place, but the American public does understand when they see Navy ships, Marines, and helicopters delivering aid to those in need – that makes sense – and it manifests the utility of the U.S. Navy’s investment in presence and forward deployment. Additionally, HA/DR is relatively inexpensive to conduct, and it can provide a sizable return on investment. Jonah Blank of RAND recently estimated that the massive U.S. response to the Indonesian “tsunami of 2004, is estimated to have cost $857 million. That’s roughly the price of three days’ operations in Afghanistan last year.” Using HA/DR to advance U.S. strategic and geopolitical goals in critical areas of the world, is a prudent use of “Smart Power” and provides “returns” on par or better than most other military operations in the public perception arena. Furthermore, the relief missions provide real world operations tempos for Navy crews, and generally provides Sailors and Marines with an immense sense of gratification by contributing tangibly to those in need – “A Global Force for Good” indeed.

Louis P. Bergeron serves in the U.S. Navy Reserve supporting the Maritime Partnership Program and works in his civilian career as a strategy consultant in the national security sector. He obtained a M.A. in Security Studies from Georgetown University in 2011 with a thesis entitled “The U.S. Navy Surface Force’s Necessary Capabilities and Force Structure for Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HA/DR) Operations” where he expounds on many of the capabilities, case studies, and platforms mentioned in this post.