A Mess

There is a general consensus in the global maritime industry that the rate of unlawful acts against vessels in the Gulf of Guinea (GoG) has been on the increase in recent years. However, information on the exact nature of such unlawful acts in the region is distorted and unreliable with confusing statistics – hampering efforts to suppress the menace. There are confusing definitions of piracy and armed robbery at sea, coupled with weak legal mechanisms for dealing with and prosecuting apprehended offenders.[1] There is also evidence suggesting that most unlawful acts against vessels in the region, irrespective of their nature or location, are erroneously being classified as acts of piracy. There have also been various allegations of low prosecution rate for apprehended offenders.

The Nature of Crimes Against Vessels in GoG from a Legal Perspective

It is vital that the exact nature of the unlawful acts against vessels in that region is established from a legal perspective so as to determine whether any counter measures, including apprehension and prosecution of offenders, should be international or nationalistic in approach or a combination of both. It seems that the confusion over the legal nature of crimes against vessels in GoG is due to the different definitions of piracy adopted by the International Maritime Bureau (IMB) and the International Maritime Organisation (IMO).

The IMB is an agency established by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) with the support of the IMO for the purpose of collecting, exchanging and disseminating information on maritime crimes for the benefit of international commerce. Until 2009 the IMB defined piracy in its annual reports as:

An act of boarding (or attempted boarding) with the intent to commit theft or any other crime and with the intent or capability to use force in furtherance of that act.[2]

The IMO is the United Nations agency with responsibility for the safety and security of shipping and the prevention of marine pollution by ships. IMO has adopted the international law definition of piracy under the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) 1982. Article 101 of UNCLOS 1982 provides that:

Piracy consists of any of the following acts:

(a) any illegal acts of violence or detention, or any act of depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or the passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft, and directed:

(i) on the high seas, against another ship or aircraft, or against persons or property on board such ship or aircraft;

(ii) against a ship, aircraft, persons or property in a place outside the jurisdiction of any State;

(b) any act of voluntary participation in the operation of a ship or of an aircraft with knowledge of facts making it a pirate ship or aircraft;

(c) any act of inciting or of intentionally facilitating an act described in subparagraph (a) or (b).

The IMO clarifies the position further with a separate definition for armed robbery against ships as follows:

1) Any illegal act of violence or detention or any act of depredation, or threat thereof, other than an act of piracy, committed for private ends and directed against a ship or against persons or property on board such a ship, within a State’s internal waters, archipelagic waters and territorial sea;[3]

2) Any act of inciting or of intentionally facilitating an act described above.

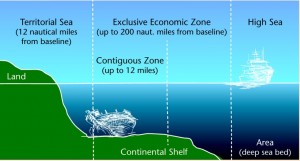

It is worthy to note that the IMB’s definition of piracy above makes no distinction as to the nature or location of unlawful acts against vessels, including unlawful acts against vessels whether in internal waters, within or outside port facilities, and whether within or outside territorial waters. On the contrary, the IMOs’ definition recognises a distinction between piracy as only occurring in international waters and all other unlawful acts within internal and territorial waters and port facilities as armed robbery. For this purpose, international waters means all maritime zones, including the Contiguous Zone,[4] the EEZ,[5] and High Seas, but excluding the Territorial and Internal waters.

Thus the distinction between Territorial Waters[6] and International waters is crucial in establishing whether a criminal act against a vessel constitutes piracy under international law. This leads to the question: what is Territorial Waters? The answer is provided by Article 3 of UNCLOS stating:

Every State has the right to establish the breadth of its territorial sea up to a limit not exceeding 12 nautical miles, measured from baselines determined in accordance with this Convention.

Under UNCLOS, a coastal state may claim right to Territorial Sea of any breadth subject to a maximum limit of 12 nautical miles from the baseline.

The IMB’s definition of piracy above may be useful for commercial expediency. However, in the quest for a strategy to tackle unlawful acts against vessels in GoG (or anywhere); including where to prosecute offenders, a legal definition will be more appropriate. Therefore it is submitted that the IMO’s definition of piracy in accordance with Article 101 of UNCLOS should be the preferred mechanism for this purpose. This is because piracy is an international crime for which every state has the right and duty to fight[7]. Theft and armed robbery within internal waters, port facilities and territorial waters is a national problem properly dealt with under the domestic laws of each country. Moreover, some of the theft and armed robberies against vessels in GoG and Nigeria in particular, are due to high level of bribery and corruption, such as port and security personnel colluding with criminals. Thus, it is not only inappropriate but it is legally wrong to describe theft and armed robbery against vessels within internal and territorial waters and port facilities as piracy.

Critics to the above position may point out that some countries, such as the United States, are yet to ratify UNCLOS. The answer to such critique is that the definition of piracy under UNCLOS is not a new concept. It is a restatement of the customary international law which was previously codified in similar language under one of the preceding conventions to UNCLOS, i.e. the High Seas Convention (HSC) 1958,[8] to which the United States and other non-UNCLOS countries are parties. Above all, as at 29 October 2013, UNCLOS had either been ratified or acceded to by 166 States worldwide[9] which makes it one of the most widely accepted international conventions of all time.

Further support as to why the definition of piracy under UNCLOS is the most appropriate mechanism for determining whether an unlawful act should be classed as such could be found from the fact that the IMB’s annual reports since 2010 adopts this view. In fairness, it seems that the IMB has taken steps to rectify the confusion with its definition of piracy, but this has not had any impact since its statistics are not broken into separate heads for international waters and territorial waters, whereas most players in the global maritime industry rely on the IMB’s statistics in making crucial decisions, such as designating High Risk Areas (HRA) as well as fixing insurance premiums and freight rates.

Statistics for crimes against vessels in GoG

Having made a case as to why the IMO’s definition of piracy based on UNCLOS should be the preferred mechanism for determining whether or not an unlawful act constitutes piracy to warrant international action, we now look at the IMO’s own statistics to ascertain the legal nature of the unlawful acts against vessels in GoG. Although the IMO’s statistics are described as a Regional Analysis on West Africa, but it relates to the whole of GoG as it includes the few reported incidents of unlawful acts against vessels in central Africa, such as the incident of the MV Kerela which took place in the internal waters of Angola on 18 January 2014.

Below is a table compiled by the IMO for unlawful acts against vessels in West Africa (including central Africa) for the period between 10 August 1995 and 6 March 2014. The table gives a breakdown of location of all reported incidents for that period, indicating the total number of reported incidents for International Waters, Territorial waters and Port area; the status of the vessels at the time of the incident – whether steaming, at anchor or unspecified; number of attackers involved; consequence of the attacks on the crew; nature of weapons used by the attackers; parts of the vessel raided; and other miscellaneous information such as number of lives lost, number of wounded crew, number of missing crew, number of crew taken hostage, number of crew assaulted and whether any ransom was paid.

IMO Regional Analysis of unlawful acts against vessels in West Africa between 10 Aug 1995 and 6 Mar 2014

| West Africa | |

| Location of incident | |

| In international waters | 158 |

| In territorial waters | 296 |

| In port area | 389 |

| Status of ship when attacked | |

| Steaming | 236 |

| At anchor | 457 |

| Not stated | 64 |

| Number of persons involved in the attack | |

| 1-4 persons | 241 |

| 5-10 persons | 208 |

| More than 10 persons | 85 |

| Not stated | 290 |

| Consequences to the crew | |

| Actual violence against the crew | 277 |

| Threat of violence against the crew | 110 |

| Ship missing | 1 |

| Ship hijacked | 36 |

| None/not stated | 223 |

| Weapons used by attackers | |

| Guns | 236 |

| Knives | 210 |

| Rocket-propelled grenades | 2 |

| Other | 30 |

| None/not stated | 336 |

| Parts of ship raided | |

| Master and crew accommodation | 18 |

| Cargo area | 152 |

| Store rooms | 261 |

| Engine room | 5 |

| Main deck | 9 |

| Not boarded | 166 |

| Not stated | 66 |

| Other | |

| Lives lost (unit: people) | 46 |

| Wounded crew (unit: people) | 181 |

| Missing crew (unit: people) | 7 |

| Crew hostage (unit: people) | 519 |

| Assaulted (unit: people) | 173 |

| Ransom | 0 |

| Total number of incidents reported per area | 843 |

Source: http://gisis.imo.org/Public/PAR/Reports.aspx?Name=RegionalAnalysis

From the IMO’s Regional analysis on maritime crime in West Africa above, it could be seen that a total of 843 reported incidents of unlawful acts against vessels took place in the more than 18 year period between August 1995 and March 2014. Out of the above figure, only 158 reported incidents took place in international waters which could legally be classified as acts of piracy. Of the remaining 685 reported incidents for that period, 296 incidents took place in Territorial Waters and 389 incidents took place in port areas.

Based on the IMO Regional Analysis above, it is clear that more than 81% of the reported incidents of unlawful acts against vessels in the West African region (and indeed GoG) should be properly and legally classified as armed robbery, whereas piracy accounts for less than 19% of such incidents.

Suggested Solutions for Dealing with the Menace

In formulating an effective strategy to repress the surge in unlawful acts against the safety of maritime navigation in GoG it is vital that we first appreciate the exact nature of the problem from a legal perspective. This is based on simple logic because it is impossible to have an effective solution to a problem without establishing the nature of the problem. The necessary corollary for that reasoning is that for any security measure to be fruitful in combating crimes against vessels in GoG it must be based on a sound legal footing bearing in mind the rights and obligations of states within the various maritime zones under UNCLOS with issues relating to sovereignty and jurisdiction, and the various maritime boundary disputes which abound in the region due to the presence hydrocarbons. Examples of maritime boundary disputes which could hinder collaborative efforts for maritime security measures in GoG include the acrimonious dispute over Bakassi peninsular between Nigeria and Cameroon; Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea over the island at the estuary of river Ntem; Equatorial Guinea and Gabon over Corisco Bay and Mbane Island; Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire over the Dzata-1 oil well near Cape Three points, as well as the potential maritime disputes between Liberia and its western and eastern neighbours following the recent discovery of oil in its waters. It is important for GoG states to set up necessary mechanisms for peaceful resolution of maritime boundary disputes as provided under UNCLOS,[10] as failure to do so may potentially derail maritime security initiatives in the region.

Based on the IMO statistics above it is safe to conclude that more than 81% of the crimes against maritime navigation in GoG is armed robbery (and theft) within territorial and internal waters including port facilities, most of which take place within Nigerian waters, as opposed to piracy in international waters. It is also obvious that the immediate threats offshore have its roots ashore. Therefore any strategy to deal with the problem effectively must be aimed at tackling both ends simultaneously.

Suggested solutions for dealing with the problem are as follows:

A) Tackling the problem offshore:

i. Littoral states in GoG must first recognise that it is the primary responsibility of each coastal state, not the international community, to secure its internal waters and port facilities as well as individual territorial waters. This is a fundamental factor that must be appreciated to ensure an endearing and effective maritime security in the region. This is because the sovereignty of a state extends to its territorial waters and the state has exclusive jurisdiction and competence to ensure the good order and security of its territorial waters. Thus every coastal state has a legal responsibility by way of a duty of care to provide proper and adequate security for maritime traffic in its territorial waters. There seems to be good arguable grounds to say that a coastal state that fails to provide proper and adequate security in its territorial waters in accordance with the requirements of UNCLOS may be liable for breach of that duty of care to victims of maritime crimes in their territorial waters and port facilities by virtue of the doctrine of State Responsibility. Of course such liability will depend on the facts of each case and may be easily established against coastal states with weak maritime security due to bribery and corruption and / or bad governance.

ii. GoG States, especially Nigeria, should adopt a zero tolerance policy to all forms of offshore bunkering activities. This is because the surge in maritime crimes in GoG is intrinsically linked to the illegal activities in the oil industry in that region, particularly Nigeria. Offshore bunkering activities in that region often entails a lot of underhand dealings with bent tycoons, which is a potential ground for organised crime and other illegal activities, including rivalry among criminal gangs, some of which ultimately lead to attacks on vessels. Therefore the recent decision by the Nigerian government to legalise offshore bunkering with a view to curtail illegal oil exports will be counterproductive to maritime security initiatives as security operatives will be placed in the difficult position of having to differentiate between legal and illegal bunkering in their operations.

iii. GoG States need to adopt firm and aggressive anti-smuggling measures with zero tolerance for such activities. Smuggling is the backbone of criminal acts against vessels and seafarers. This is because the clandestine nature of smuggling which is carried out to evade payment of customs and port duties are often conducted sneakily without security protection, thereby creating the propensity for criminal activities which leads to attacks on vessels. Crimes against vessels in GoG is an offshoot of the high rate of smuggling by sea in the region, which has always been a means for trafficking in weapons and narcotics as well as other illicit activities because it gives the perpetrators the confidence to undermined any security regime in the region. Thus any initiative to suppress piracy and armed robbery at sea in GoG will not achieve any meaningful result without curbing the high rate of smuggling in the first instance. In short, anti-smuggling initiatives should be used as a barometer in the quest for suppression of unlawful acts against the safety of maritime navigation in GoG.

iv. Coastal states in GoG need to give priority to removal of shipwrecks from their waters and to have stringent measures to prevent abandonment of vessels. The reason for this is that proliferation of abandoned vessels in the region are not only a source of navigational and environmental hazards, but they also provide cosy nests for maritime criminals to store arms and launch attacks on vessels. Wherever possible, the relevant authorities should identity owners of abandoned vessels from names of the vessels and other identification marks, and to get them to pay for the cost of removal of such wrecks. In this regard it should be noted that the Nairobi International Convention on the Removal of Wrecks (the Convention) which was adopted by the IMO on 18 May 2007 will come into force on 14th April 2015, being twelve months after the ratification of the 10th country for that convention i.e. Denmark. The ten countries that ratified the Convention to bring it into force on the above date are: Bulgaria, Denmark, Germany, India, Iran, Malaysia, Morocco, Nigeria, Palau and United Kingdom. Under the convention, all vessels of 300 gross tonnes and above registered in any state which is a party to the convention or calling at ports and terminals in those states must have evidence of insurance policy to cover wreck removal. The convention only applies in the EEZ, but there is a provision under Article 3 for states to extend its application to their territories, including territorial and internal waters, where most shipwrecks occur due to higher risk of grounding. Denmark’s ratification of the Convention made it the third country along with Bulgaria and the United Kingdom, to extend its application to their territories. In view of the high rate of abandoned vessels within the territorial and internal waters of Nigeria and other states in GoG, it will be highly appropriate for the Nigerian authorities to rely on Article 3 of the convention to extend its application to their territory, and for other GoG states to ratify the convention and do the same.

v. Combating maritime crime in GoG does not require more warships because it is obvious that the root cause of the problem is ashore, as opposed to offshore. Maritime criminals in that region will always try their luck in view of the highly lucrative nature of such illegal activities compared to the low risk of apprehension and prosecution. Therefore naval and coast guard activities should be conducted with the aim to deter, detect and defeat maritime criminals before they are able to carry out any successful operation. What is required for this purpose is the capability for the authorities to have virtual control of their maritime environment so that the presence of security operations could be seen and felt by prospective criminals, which cannot be achieved with warships, but with fast and well equipped patrol boats that are able to outsmart speed boats used by criminals, with more emphasis on use of aircraft equipped with the necessary tools and equipment to undertake far reaching aerial surveillance and able to get to the location of any reported incident in the shortest possible time, all of which must be supported with modern technology to capture the activities and movements of all types of vessels, large or small. There is a need for more and well equipped faster patrol boats manned by properly trained officers. In view of the large expanse of the area to be kept under surveillance, it will be cost effective and the naval and coastguard forces would benefit from Maritime Airborne Surveillance and Control (MASC). Thus, in addition to better equipped and fast patrol boats, what is required is more patrol and reconnaissance aircraft with multiple capabilities, supplemented with extensive use of modern technology. Of course, it will also require the hardening, reinforcement and co-ordination of the existing naval and coastguard capabilities of GoG states to ensure efficient and regular patrol by well trained officers, as well as instilling more discipline and professionalism in the naval forces, for effective maritime law enforcement. This is will be particularly useful in the case of Nigeria in view of the endemic allegations of corruption within the Nigerian navy.

vi. GoG States must invest in modern technology in their efforts to combat maritime crime due to the large expanse of the area to be kept under surveillance. With modern technology which is constantly improving, it is possible for the authorities to have virtual control of their maritime domains by investing in various maritime surveillance systems to complement water and aerial patrols. Whilst technology enhances maritime security, no technological system will provide full proof surveillance, and some may need to be integrated with others to increase reliability. Choosing the right technology also requires careful consideration of prevailing local circumstances and available infrastructure, such as frequent disruption to electricity supply especially in Nigeria, in order to be of any benefit. Examples of available technology for maritime security surveillance are:

Automatic Identification System (AIS) This is a navigational aid which broadcasts information about a vessel to other vessels and to shore-based authorities automatically. The requirement for vessels to have AIS was adopted by the IMO as Regulation 19 of Chapter V of the International Convention on Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) 1974 as amended. The Regulations make it a mandatory requirement for AIS to be fitted on all vessels of 300 gross tonnes or more engaged on international voyages and cargo ships of 500 gross tonnes or more not engaged on international voyages and all passenger vessels irrespective of size, with effect from 31 December 2004. To ensure effective maritime security, all GoG states should consider adopting and implementing the above AIS Regulations (where they have not done so) and to make it a compulsory requirement for all vessels (irrespective of size) to be fitted with AIS, with a zero tolerance policy for any vessel to operate in their maritime domain without AIS. Such a requirement will make it possible for all vessels to be tracked and suspicious vessels interdicted before any atrocities are committed. AIS is useful for short range vessel identification and tracking.

Long-Range Identification and Tracking (LRIT) system is a global messaging system for security as well as Search and Rescue purposes. LRIT system was adopted by the IMO and came into force on 1 January 2008 through Regulation 19-1 of Chapter V of SOLAS. The LRIT Regulations require passenger ships on international voyages including high-speed craft, cargo ships including high speed craft of 300 gross tonnes and above, as well as mobile drilling units, to transmit information relating to identity and location specifying position, date and time for a vessel to their Flag State at least every 6 hours. Flag States maintain a database for such transmitted information to share with any other State which is a party to SOLAS Convention, upon request. Thus coastal States may request information on any vessel which is within 1000 nautical miles from their coast. The Flag State will release such information to the requesting state unless there are reasons not to do so on grounds of confidentiality. There is no interface between LRIT and AIS. The IMO has since set up an Information Distribution Facility (IDF) to provide LRIT data from SOLAS member states to naval forces in the suppression of crime against vessels in Gulf of Aden and wider Indian Ocean. The IMO issued a circular on 6 December 2010 advising SOLAS member states that North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) and EU NAVFOR are involved with the IDF and urged Flag States to provide LRIT information to those organisations, on request.

Vessel Monitoring Systems (VMS) is a satellite-based monitoring system capable of providing information on the location, speed and course of a vessel. VMS is mostly used for purposes of monitoring fishing vessels, but could equally be used for purposes of security surveillance. It will be helpful to make it mandatory for vessels to have VMS to report the location of ships at regular interval.

Vessel Detection System (VDS) which makes it possible for vessels to be detected through Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) under any weather condition, day and night. This is a vital tool in maritime security surveillance because detecting the position of vessels neither requires co-operation of vessels nor voluntary disclosure of information by vessels. Thus VDS makes it possible for suspicious vessels to be detected and reported to relevant naval and coastguards for interception.

Vessel Traffic Services (VTS) System involves having a station ashore with sensors, radars and optical or infrared cameras for trained personnel to monitor local maritime traffic. VTS systems are used in areas of heavy maritime traffic to ensure safety of navigation but could also be useful for purposes of maritime security surveillance.

B) Tackling the problem ashore:

vii. GoG states must give priority to Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) in their national security policies. The Maritime Domain of a coastal state is all areas and things of, on, under, relating to, adjacent to, or bordering on a sea, ocean, or other navigable waterway, including all maritime-related activities, infrastructure, people, cargo, vessels, and other conveyances. MDA on the other hand is the appreciation of everything relating to the maritime domain with the potential to affect the security, safety, economy, or environment of a coastal state. GoG states rely heavily on their Maritime Domain as a major source of revenue. Maritime insecurity in GoG is a direct consequence of the fact that until recently most states in the region overlooked the need for any or proper MDA programmes as they concentrated mainly on land security with little or no attention for their maritime domains. Thus GoG states must have long term MDA Plans in their security policies. Such MDA plans must be tailored to the peculiar needs of each state bearing in mind their social, economic and political circumstances. The MDA plans must be reviewed regularly to ensure efficacy, as well as anchored to regional and international MDA plans. Maritime security initiatives are unlikely to be effective unless GoG states engage in long term and sustained MDA programmes to complement such efforts.

viii. Coastal States in GoG need to appreciate that maritime activity is the mainstay for their economies and the need to guard that source of income jealously by allocating adequate and commensurate resources for maritime security. Of course this should go hand in hand with having an effective system to ensure that allocated resources are utilised for the intended purpose. It seems that the situation has got this bad because, while all littoral states in GoG derive most of their revenue from their maritime domain, they have not been enthusiastic about allocating adequate resources for purposes of maritime security. This can be seen from the fact that most GoG states do not have any or adequate naval or coastguard capabilities, apart from Nigeria and Ghana who have some naval capability to operate at sea for a reasonable period. Nigeria has the largest navy in the region but its operational capability had been undermined for years by lack of maintenance of its fleet and equipment due to inadequate funding amidst allegations of mismanagement, though it seems that situation is currently being addressed following the recent intervention of Nigeria’s Senate Committee on the Navy.[11]

ix. It is of utmost importance for GoG states to initiate viable welfare programmes by boosting job opportunities in their coastal communities, to engage those who are enticed into criminal activities as a way of survival. This is particularly important as almost all GoG states have no social security systems for those who are unemployed to fall back on. Thus most unemployed people in the region resort to survival by all means, often with no regard for law and order. This problem is particularly acute in Nigeria being the most populous and richest country in the region, but with a very high unemployment and poverty rate. The problem is aggravated by government policies which are not given careful consideration before implementation, such as the privatisation of Nigerian seaports in which resulted in mass redundancies of about 18,000 people in 2006 within the maritime sector, thereby increasing the number of unemployed people with links to the maritime sector to increase the regiment of maritime criminals. No maritime security initiative is likely to yield any positive result so long as there remain a high number of people with links to the maritime sector, including maritime security sector, with no source of livelihood. There is an urgent need for aggressive job creation programmes within the coastal communities. One way in which this may be done is by rejuvenating the fishing sector which has been neglected as a result of the booming petroleum industry by clamping down on Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fishing, to absorb some of those artisans and security personnel who were affected by the mass redundancies in the maritime sector. Reviving the erstwhile thriving agricultural sector which has also been abandoned for same reason will go a long way to ameliorate the problem.

x. The root causes of maritime crimes in GoG in general and Nigeria in particular are bribery and corruption coupled with weak governance, which is responsible for the high rate of poverty and consequential crimes in the region. Attaining effective maritime security in GoG will remain elusive so long as millions of people are deprived of basic necessities of life such as food, shelter, employment, and access to proper medical facilities. The situation is worsened by the fact that such detrimental activities are perpetuated by some of those who are charged with the responsibility of managing affairs of the state and ensuring law and order. In some instances, government policies and actions amount to nothing short of blatant disregard for the law. This is why the ordinary citizens have no regard for law and order or any form of constituted authority because they do not see or feel any positive impact of the government. Our government is the potent, the omnipresent teacher. For good or for ill, it teaches the whole people by its example. Crime is contagious. If the government becomes a lawbreaker, it breeds contempt for law; it invites every man to become a law unto himself; it invites anarchy.[12] There is urgent need for improved governance and for existing anti-bribery and corruption laws to be vigorously enforced. The remedies for crime are good governance, accountability and transparency underpinned with respect for rule of law by the custodians of the law for the general population to emulate. Unfortunately actualisation of those simple remedies for the depravity may be the hardest part in the quest to suppress the general insecurity in the region because it will require some form of mass social mobilisation with the aim of complete reorientation and change in mindset from the leaders and the general population.

xi. There is an urgent need for GoG states to review and overhaul existing legal mechanisms for the prosecution of criminals apprehended for maritime crimes. Such an exercise is necessary in view of the various allegations of corruption against the prosecuting authorities and members of the judiciary who are involved in dealing with such cases, especially in Nigeria. This is because the current low prosecution rate compared to the number of apprehended offenders is an incentive for such acts to continue. In order to deal with the unsatisfactory state of affairs regarding prosecution of maritime criminals, it will be helpful for GoG states to consider pulling their resources to establish a specialist regional tribunal to try such cases. This may entail having to amend their domestic criminal laws to give harmonised jurisdiction to such a specialised regional tribunal to try cases of maritime crimes committed within the territorial waters of member states. The different legal systems of the various Anglophone, Francophone and Lusophone countries in the region should not be an obstacle as there are several international criminal courts and tribunals with templates for such initiative. Having such a regional specialised tribunal will send a strong message to maritime criminals and their ‘godfathers’ that GoG states are all out to combat maritime crimes in the strongest terms, which will serve as a durable deterrent.

xii. GoG states need to engage in greater regional cooperation in the fight against maritime crimes. The porous and contiguous nature of maritime boundaries means that maritime crimes cut across national jurisdictions and this may occur easily in GoG where most maritime boundaries have not been clearly demarcated resulting in various maritime boundary disputes, which may lead to allegations of transgression. Therefore there is a need for coordination of efforts and resources as well as information sharing between GoG states in the quest for repression of maritime crimes. The Yaoundé Code of Conduct concerning the repression of piracy, armed robbery against ships, and illicit maritime activity in West and Central Africa (Yaoundé Code of Conduct) which was adopted on 25 June 2013 is a laudable step in the right direction because it demonstrates that the governments of GoG states are ready to put aside their differences from the relics of colonialism to combat a common problem. Unfortunately, despite its ambitious aims, the Yaoundé Code of Conduct deals with only the symptoms of the problem by addressing offshore threats, without addressing the root causes of the problem ashore. For instance, it does not propose a solution for the low prosecution rate for apprehended maritime criminals in the region. Rather, the relevant provisions relating to prosecution of apprehended maritime criminals under the Yaoundé Code of Conduct merely provides that:

The Signatories intend to prosecute, in their domestic courts and in accordance with relevant domestic laws, perpetrators of all forms of piracy and unlawful acts against seafarers, ships, port facility personnel and port facilities.[13]

The organization and functioning of this national system is exclusively the responsibility of each State, in conformity with applicable laws and regulations.[14]

…..each Signatory to the fullest possible extent intends to co-operate in arresting, investigating, and prosecuting persons who have committed piracy or are reasonably suspected of committing piracy.[15]

This is a serious deficiency in the Yaoundé Code of Conduct because the low prosecution rate for apprehended maritime criminals in GoG is a big incentive for such acts to continue. The failure of the Yaoundé Code of Conduct to address the root causes of the problem ashore may be attributable to the fact that it was deliberated upon and adopted by officials of the same governments who will not accept any allegations of bad governance and corruption. The effectiveness of the Yaoundé Code of Conduct as a tool for combating maritime crimes in GoG will be greatly improved if it is amended to also deal with the root causes of the problem ashore, such as establishing a specialised regional tribunal for prosecution of maritime criminals. Such initiative will address the problem of low prosecution rate and serve as a strong deterrent for maritime criminals.

Conclusion

It is indisputable that there has been a significant increase in the number of attacks on vessels in GoG and that most of such activities take place within Nigerian waters. However, the exact nature of the attacks seems tangled due to the confusing definitions of piracy used by the major organisations interested in global maritime affairs, as a result of which even theft within port facilities and anchorage areas are classed as piracy. This article has sought to untangle the exact nature of such illegal activities in GoG from a legal perspective, using the most authoritative and widely accepted definition of piracy under UNCLOS which reflects the customary international law position, to the effect that piracy is a universal crime which can only be committed in international waters.

Relying on IMO statistics over an 18 year period from 1995 to 2014 which are based on the UNCLOS definition of piracy, it is evident that more than 81% of such unlawful activities are acts of armed robbery (and some theft) as opposed to piracy because they occur within territorial and internal waters, including port facilities, and not in international waters. Therefore it is safe to conclude that the legal responsibility for dealing with the problem is that of the national governments in GoG as opposed to the international community. The concept of independence and equality of states imposes a duty on countries to refrain from intervention in the internal or external affairs of other countries.[16] Thus, any intervention from the international community without a formal invitation from or the consent of the states concerned, which will of course require a consensus from all the affected states in GoG, will amount to a violation of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of those states. Whilst only about 19% of the problem could be properly classified as piracy to warrant international intervention, any support from the international community to stem the menace will be highly beneficial to the global community in view of the adverse impact on international trade.

Unlike other regions in the world with similar problem such as Gulf of Aden and Malacca Straits, maritime crime in GoG is a convoluted issue because of the peculiarity of such activities in the region. The foremost reason for this is because the menace is a spin-off from the mismanagement of the abundant hydrocarbons in the region, especially in Nigeria’s Niger Delta. Thus it is not surprising that the militants who have been engaged in violent agitation for ‘resource control’ of the crude oil exploited from the Niger Delta have been singled out as the culprits for the surge in attacks on vessels in GoG. The reality of the situation is more intricate than that, as a careful examination of the causes of the problem indicates that it is rooted in the high level of bribery and corruption with lack of good governance in the region, especially Nigeria, coupled with indifference to MDA among GoG states generally. The real culprits include corrupt public and political office holders who recruit criminals to commit various atrocities including attacks on vessels;[17] low and high ranking officers in the armed forces and security services in the maritime sector who abuse their position by engaging in unlawful acts; greedy workers for Multi-National Oil companies and shipping companies who facilitate attack on tankers by providing information to criminals on movement of oil tankers; prosecutors and judicial officers who accept kickbacks in return for not prosecuting apprehended criminals or for trials to falter; as well as greedy foreigners who collude with crooked indigenes to carry out illegal bunkering activities.

Irrespective of the complexities surrounding maritime crimes in GoG, the problem is not beyond subjugation and should not go unchecked. Unfortunately most of the efforts made so far to tackle the menace have been aimed at the symptoms of the problem offshore, with little or no attention in dealing with the root causes of the problem ashore. In finding a lasting solution, efforts must be made to deal with both ends of the problem concurrently. There is an imperative need for the unlawful acts against the safety of maritime navigation in GoG to be nipped in the bud. Crime is contagious, and the negative successes of the terrorist groups in the Sahel, especially the recent atrocities of Boko Haram with the Chibok abductions in Bornu state of north eastern Nigeria may be transposed into the maritime domain, if no firm action is taken to check the situation swiftly. GoG states need to change their mindset from thinking of the cost of having adequate and effective maritime security. Rather, they need to start thinking of how much they stand to lose by not having proper, adequate and effective security in their maritime domains.

References

[1] Maritime Security in the Gulf of Guinea, Report of Conference held at Chatham House, London, 6 December 2012, p.9

[2] ICC International Maritime Bureau, Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships, Report for the Period 1 January to 30 June 2009, p.3; 2009 q2 imb piracy report (1).pdf

[3] Code of Practice for the Investigation of Crimes or Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships, IMO Resolution A.1025(26), Adopted on 2 December 2009.

[4] The Contiguous Zone is the maritime zone immediately after the Territorial Sea, up to a further limit of 12 nautical miles after the Territorial Sea (or 24 nautical miles from the baseline inclusive of the Territorial Sea) and within which a coastal state has limited powers to enforce its fiscal, customs, sanitary and immigration laws. Article 33 of UNCLOS.

[5] The EEZ is a maritime zone which extends up to 200 miles from the baseline, and in which coastal states enjoy extensive rights as regards natural resources and jurisdictional rights, while other states enjoy the freedom of navigation, over flight, laying of submarine cables and pipelines; Articles 55 – 58 of UNCLOS 1982

[6] The Territorial Sea, sometimes referred to as Territorial Waters, is the immediate maritime zone measured from the baseline of a coastal state and extends up to 12 nautical miles into the sea. Article 3 of UNCLOS

[7] Churchill. R. R. and Lowe. A. V, The Law of the Sea, Third Edition, Manchester University Press, 1999, p.209

[8] Article 15 of HSC 1958 provides that Piracy consists of any of the following acts:

(1) Any illegal acts of violence, detention or any act of depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or the passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft, and directed:

(a) On the high seas, against another ship or aircraft, or against persons or property on board such ship or aircraft;

(b) Against a ship, aircraft, persons or property in a place outside the jurisdiction of any State;

(2) Any act of voluntary participation in the operation of a ship or of an aircraft with knowledge of facts making it a pirate ship or aircraft;

(3) Any act of inciting or of intentionally facilitating an act described in sub-paragraph 1 or sub-paragraph 2 of this article.

[9] http://www.un.org/Depts/los/reference_files/chronological_lists_of_ratifications.htm

[10] Articles 279 – 285 of UNCLOS 1982

[11] http://www.thisdaylive.com/articles/senate-in-move-to-revamp-nigerian-navy/115222/

[12] Justice Louis D. Brandeis in the case of Olmstead-v-United States, 277 U.S. 438, 485 (1928)

[13] Article 4(4) of Yaoundé Code of Conduct

[14] Article 4(5) of Yaoundé Code of Conduct

[15] Article 6(1)(a) of Yaoundé Code of Conduct

[16] Brownlie, I., Principles of Public International Law, Seventh Edition, Oxford University Press, 2008, p.29

[17] http://www.vanguardngr.com/2012/12/top-government-officials-politicians-contract-us-sea-pirates/

Short Bio

Herbert I. Anyiam LLB(Hons), BL, LLM, MCIArb. Herbert is the CEO of Global Maritime Bureau, an international maritime consultancy firm in the UK. He is a dual qualified lawyer in England & Wales and Nigeria and a member of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators. He is an expert in international maritime and admiralty law, international dispute resolution services and multi-jurisdictional disputes. He is a Supporting member of London Maritime Arbitrators Association (LMAA), member of the International Maritime Statistics Forum (IMSF) and a member of International Maritime Organisation (IMO) Roster of Expert Consultants.