The following is adapted from the Center for Naval Analyses report Becoming a Great “Maritime Power”: A Chinese Dream. Read a similar article adaptation at The National Interest.

By Michael McDevitt

Introduction

In November 2012, then president Hu Jintao’s work report to the Chinese Communist Party’s 18th Party Congress was a defining moment in China’s maritime history. Hu declared that China’s objective is to be a haiyang qiangguo—that is, a strong or great maritime power. China “should enhance our capacity for exploiting marine resources, develop the marine economy, protect the marine ecological environment, resolutely safeguard China’s maritime rights and interests, and build China into a strong maritime power” (emphasis added).1

Hu’s report also called for building a military (the PLA) that would be “commensurate with China’s international standing.” These two objectives were repeated in the 2012 PRC defense white paper, which was not released until April 2013, after Xi Jinping had assumed Party and national leadership.

According to the white paper:

“China is a major maritime as well as land country. The seas and oceans provide immense space and abundant resources for China’s sustainable development, and thus are of vital importance to the people’s wellbeing and China’s future. It is an essential national development strategy to exploit, utilize and protect the seas and oceans, and build China into a maritime power.”2

Answering the obvious questions

The study upon which this paper is based addressed a number of questions related to what China’s aspirational goal actually means.3 These are summarized below:

How does China understand the idea of maritime power?

In the Chinese context, maritime power encompasses more than naval power but appreciates the importance of having a world-class navy. The maritime power equation includes a large and effective coast guard; a world-class merchant marine and fishing fleet; a globally recognized shipbuilding capacity; and an ability to harvest or extract economically important maritime resources, especially fish.

The centrality of “power” and “control” in China’s characterization of maritime power

In exploring how Chinese commentators think about maritime power, it was instructive to note how many Chinese conceptualizations included notions of power and control. For example, an article in Qiushi, the Chinese Communist Party’s theoretical journal, stated that a maritime power is a country that could “exert its great comprehensive power to develop, utilize, protect, manage, and control oceans.” It proceeded to opine that China would not become a maritime power until it could deal with the challenges it faces in defense of its maritime sovereignty, rights, and interests, and could deal with the threat of containment from the sea.

Why does China want to become a maritime power?

China’s strategic circumstances have changed dramatically over the past 20 years. The growth in China’s economic and security interests abroad along with longstanding unresolved sovereignty issues such as unification with Taiwan and gaining complete control of land features in the East and South China Seas. Of perhaps equal importance, Xi Jinping has embraced maritime power as an essential element of his “China Dream,” leading to a Weltanschauung within the Party and PLA that becoming a “maritime power” is a necessity for China.4

Finally, it wants to be a maritime power because it deserves to be; China’s reading of history concludes that maritime power is a phenomenon associated with most of the world’s historically dominant powers.5

Anxiety regarding the security of China’s sea lanes

China’s leaders worry about the security of its seaborne trade. The prominence given to sea lane protection and the protection of overseas interests and Chinese citizens in both the 2015 defense white paper and The Science of Military Strategy makes clear that sea lane (SLOC) security is a major preoccupation for the PLA. Chinese security officials can read a map, they appreciate the vulnerability of China’s SLOCs; a concern reinforced by U.S. and western security analysts who write frequently about interrupting China’s sea-lanes in times of conflict.6

When will China become a maritime power?

Remarks made by senior leaders since 2012 make it clear that the long-term goal is for China to be a leader across all aspects of maritime power; having some of these capabilities means that China has some maritime power but that it is “incomplete.” The research for this paper strongly suggests that China will achieve the goal of being the leading maritime power in all areas except its navy, by 2030.

Is becoming a “maritime power” a credible national objective?

China is not embarking on a maritime power quest with the equivalent of a blank sheet of paper. In a few years it will have the world’s second most capable navy. China is already a world leader in shipbuilding, and it has the world’s largest fishing industry. Its merchant marine ranks either first or second in terms of total number of ships owned by citizens. It already has the world’s largest number of coast guard vessels.

The United States inhibits accomplishing the maritime power objective

A significant finding is that from a Chinese perspective U.S. military presence in the Western Pacific impedes Chinese maritime power ambitions. To Beijing, the U.S. rebalance strategy exacerbates this problem. For China to satisfy the maritime power objective, it must be able to defend all of China’s maritime rights and interests in its near seas in spite of U.S. military presence and alliance commitments. In short, it must be able to successfully execute what the latest defense white paper terms “offshore waters defense” for China to be considered a maritime power.

The maritime power vision is global

A wide variety of authoritative sources indicate that maritime power will also have an important global component. The latest Chinese defense white paper indicates that PLA Navy strategy is transitioning from a single-minded focus on “offshore waters defense,” to broader global strategic missions that place significant importance on “distant-water defense.”

Assessing the Elements that Constitute China’s Maritime Power

The PLA Navy (PLAN)

When one counts the number and variety of warships that the PLAN is likely to have in commission by around 2020, China will have both the largest navy in the world (by combatant, underway replenishment, and submarine ship count) and the second most capable “far seas” navy in the world.

To this point, when comparing PLAN’s “blue water” or “far seas” capabilities projected to circa 2020, to other “great” navies of the world, navies that have the experience and capabilities necessary to conduct sustained deployments very far from home waters, the results are interesting. The PLAN will have:

- A well balanced fleet in terms of the full range of naval capabilities— a smaller version of USN

- As many nuclear attack submarines (6-7) as UK and France, third behind US and Russia.

- More SSBNs (5-7) than UK and France, third globally.

- As many aircraft carriers (2) as the UK and India.

- 18-20 AEGIS like destroyers—second globally, more than Japan’s 8.

- More modern multi-mission frigates (FFG) (30-32) than any other navy.

- A blue-water amphibious force second only to USN in large (LPD/LSD) class ships (6-7)

- A modern underway replenishment force, behind only the US.

- A “new far seas” navy; all warships built in 21st century

The total “far seas” capable warships/underway replenishment/submarines forecast to be in PLAN’s inventory around 2020 total between 95 and 104 major warships. If one adds this number to the 175-odd warships/submarines the PLAN has commissioned since 2000 that are largely limited to near seas operations and likely will still be in active service through 2020, the total PLAN warship/replenishment/submarine strength circa 2020 is in the range of 265-273.

This raises the obvious question; how does this stack-up versus the U.S. Navy? The USN will have many more high-end ships in 2020 than the PLAN, including 11 CVNs, 88-91 AEGIS warships, 51 nuclear powered attack submarines, 4 nuclear powered land–attack cruise missile submarines, 14 SSBNs, 33 modern amphibious ships, and 30 odd underway replacement ships. If one also includes 28 Littoral Combat Ships (LCS), the U.S. Navy is projected to have a force structure of around 260 warship/replenishment/submarines in 2020; in short, the USN and PLAN will be in a position of rough numeric party, but the USN will maintain a wide qualitative advantage.

If current plans are carried through, some 60 percent of the total USN force structure, or around 156 warships and submarines, will be assigned to the U.S. Pacific Fleet by 2020. So, while the U.S. number includes more high-end ships, the total number of combatants the PLAN would have at its disposal for a defensive campaign in East Asia is significant. In this sort of defensive campaign (A2/AD) one must also consider the land based aircraft of PLA Navy and the PLA Air Force as well as the Strategic Rocket Force’s anti-ship ballistic missiles.

How large will the PLAN become?

We don’t know. This is the biggest uncertainty when considering China’s maritime power goal, because China has not revealed that number.

The China Coast Guard (CCG)

The China Coast Guard already has the world’s largest maritime law enforcement fleet. As of this writing, the Office of Naval Intelligence counts 95 large (out of a total 205) hulls in China’s coast guard.7 Chinese commentators believe that China cannot be considered a maritime power until it operates a “truly advanced” maritime law enforcement force. The key will be the successful integration of the discrete bureaucratic entities that have been combined to form the coast guard, and much work remains to be done on this score.

The maritime militia—the third coercive element of China’s maritime power

One of the most important findings of this project is the heretofore underappreciated role that China’s maritime militia plays, especially in the South China Sea. Often, it is China’s first line of defense in the maritime arena. It has allowed China to harass foreign fishermen and defy other coast guards without obviously implicating the Chinese state.

Shipbuilding and China as a maritime power

China became the world leader in merchant shipbuilding in 2010. For the last several years, global demand has shrunk significantly, and China, along with other builders around the world, now faces the reality that it must shed builders and exploit economies of scale by consolidating and creating mega-yards. In short, for China “… to move from a shipbuilding country to shipbuilding power,” it has to focus on quality above quantity.

China’s merchant marine

China’s current merchant fleet is already world class. Beijing’s goal is to be self-sufficient in sea trade. During the past 10 years, the China-owned merchant fleet has more than tripled in size. In response to the Party’s decision for China to become a maritime power, the Ministry of Transport published plans for an even more competitive, efficient, safe, and environmentally friendly Chinese shipping system by 2020.

Fishing is an element of China’s maritime power

China is by far the world’s biggest producer of fishery products (live fishing and aquaculture). It has the largest fishing fleet in the world, with close to 700,000 motorized fishing vessels, some 200,000 of which are marine (sea-going) with another 2,460 classified as distant-water (i.e., global, well beyond China’s seas) in 2014.8 The fishing industry is now viewed in strategic terms; it has a major role in safeguarding national food security and expanding China’s marine economy.

Beijing’s views on its maritime power: What are the shortfalls?

When one considers all the aspects of maritime power—navy, coast guard, militia, merchant marine, port infrastructure,9 shipbuilding, fishing—it is difficult to escape the conclusion that China already is a maritime power, at least in sheer capacity. No other country in the world can match China’s maritime capabilities across the board.

So what is the problem?

Why do China’s leaders characterize becoming a maritime power as a future goal, as opposed to asserting that China is a maritime power? Chinese experts think that China has to improve in several areas:

- The China Coast Guard needs to complete the integration of the four separate maritime law enforcement entities into a functionally coherent and professional Chinese coast guard.

- Increased demand for more protein in the Chinese diet means that the fishing industry—in particular, the distant-water fishing (DWF) component—must expand and play a growing role in assuring China’s “food security.”

- Chinese projections suggest that by 2030 China will surpass Greece and Japan to have the world’s largest merchant fleet by DWT10 and that its “international shipping capacity” will double, to account for 15 percent of the world’s shipping volume. China’s goal is that 85 percent of crude oil should be carried by Chinese-controlled ships. China will become the largest tanker owner by owner nationality around 2017-18.

- China’s shipbuilding sector is facing a serious period of contraction; thus, the biggest shortcoming is trying to preserve as much capacity as possible: among other things, thousands of jobs are at stake. Chinese builders are also working to ensure the future health of the industry by building economically competitive complex ships and thereby moving up the value chain.

- China’s most serious impediment to becoming a maritime power is its navy. It wants its navy to be able to deal with the threat of containment, defend its sea lanes, and look after global interests and Chinese citizens abroad. Chinese assessments quite logically conclude that until its navy can accomplish these missions China will not be considered a maritime power.

When will China Become the Leading Maritime Power?

From the perspective of spring 2016, none of these shortcomings appear insurmountable. Past performance suggests that China is likely to achieve all of its maritime power objectives, except perhaps one, sometime between 2020 and 2030.

Shortcomings in the coast guard, maritime militia, and fishing industry are likely to be rectified by around 2025. Chinese experts estimate that the merchant marine objectives will be accomplished by around 2030. China seems determined to move up the value/ship complexity scale in shipbuilding. This is will depend on the success of China’s attempts to create mega-yards to capitalize on economy of scale.

China is forecast to have a larger navy than the United States in five years or so if one simply counts numbers of principal combatants, underway replenishment ships and submarines—virtually all of which will be available in East Asia, facing only a portion of the USN in these waters on a day-to-day basis. China will have a growing quantitative advantage in the Western Pacific while gradually closing the qualitative gap. China also depends on its land based air and missile forces to contribute to the defense of its home waters.

Since it is up to China’s leaders to judge when its navy is strong enough for China to be a maritime power, it is difficult to forecast a date. Their criteria for deciding when its navy meets their standards for being a maritime power are likely to revolve around several publicly stated objectives:

The first objective is to control waters where China’s “maritime rights and interests” are involved. This likely means the ability to achieve “sea and air control” over the maritime approaches to China—i.e., to protect mainland China when U.S. aircraft or cruise missile shooters are close enough to attack it, probably somewhere around the second island chain.11 “Near-waters defense,” known as A2/AD in the United States, is intended to defeat such an attack. A very important uncertainty is when, if ever, China’s leaders will come to believe that its navy can provide such a defense, because the United States is actively working to ensure that it cannot.

The second objective is being able to enforce its maritime rights and interests. If one considers this to be primarily a peacetime problem set, the combination of China’s coast guard and maritime militia are already capable of, and increasingly practiced in, enforcing Chinese rules and regulations in its territorial seas and claimed EEZ (or within the so called nine-dash line) in the South China Sea.

The third objective revolves around the ability to deter or defeat attempts at maritime containment. It is not absolutely clear what China means by “maritime containment.”

- If “maritime containment” is intended to mean a blockade, a war-time activity, the combination of the capabilities required to “control “ its maritime approaches, addressed above, plus the capabilities associated with the “open seas protection” mission addressed above, pertain.

- But if deterring maritime containment implies a peacetime activity involving the combination of Chinese conventional and nuclear capabilities and the perception that China’s leaders have the will to act, this deterrent is already in place—and will be enhanced by its newly operational SSBN force.

- Deterring maritime containment may also address the broader political-military objective of making certain that the United States and other leading maritime powers of Asia do not establish a formal defense treaty relationship where all parties are pledged to come to the aid of one another. (This seems highly unlikely because of China’s economic power, geographic propinquity, and strategic nuclear arsenal, and because it has the largest navy in Asia.)

Implications and Policy Options for the United States

Implications

Whether it is the navy, the merchant marine, or China’s distant-water fishing fleet, the Chinese flag is going to be ubiquitous on the high seas around the world. There may be far more opportunities for USN-PLAN cooperation because the PLAN ships are far removed from Chinese home waters, where sovereignty and maritime claim disputes create a different maritime ambiance.

Collectively, a number of factors—the goals for more Chinese-controlled tankers and other merchant ships, the new focus on “open seas protection” naval capabilities, the bases in the Spratlys, Djibouti, and probably Gwadar, Pakistan, and the ambitious infrastructure plans associated with the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road—suggest that China is doing its best to immunize itself against attempts to interrupt its seaborne trade by either peacetime sanctions or wartime blockades.

One implication for Washington of China’s growing “open seas protection” capable ships is that U.S. authorities can no longer assume unencumbered freedom to posture U.S. naval forces off Middle East and East African hotspots if Chinese interests are involved and differ from Washington’s. Both governments could elect to dispatch naval forces to the waters offshore of the country in question.

Once the reality of a large Chinese navy that routinely operates worldwide sinks into world consciousness, the image of a PLAN “global” navy will over time attenuate perceptions of American power, especially in maritime regions where only the USN or its friends have operated freely since the end of the Cold War.

More significantly, the image of a modern global navy combined with China’s leading position in all other aspects of maritime power will make it easy for Beijing to eventually claim it has become the “world’s leading maritime power,” and argue its views regarding the rules, regulations, and laws that govern the maritime domain must be accommodated.

Policy Options

Becoming a maritime power falls into the category of China doing what China thinks it should do, and there is little that Washington could (or should) do to deflect China from its goal. The maritime power objective is inextricably linked to Chinese sovereignty concerns, real and perceived; its maritime rights and interests broadly and elastically defined; its economic development, jobs, and improved technical expertise; the centrality of fish to its food security goals; and its perception of the attributes that a global power should possess. Furthermore, it is important because the president and general secretary of the CCP have said so.

There is one aspect of Chinese maritime power that U.S. government officials should press their Chinese counterparts to address: just how large will the PLA Navy become? The lack of Chinese transparency on this fundamental fact is understandable only if Beijing worries that the number is large enough to be frightening.

Washington does have considerable leverage on the navy portion of China’s goal because of the direct relationship between the maritime power objective and its impact on America’s ability to access the Western Pacific if alliance partners or Taiwan face an attack by China. U.S. security policy should continue to focus on and resource appropriately the capabilities necessary to achieve access, or what is now known as Joint Concept for Access and Maneuver in the Global Commons (JAM-GC).12

Conclusion

The only thing likely to cause China to reconsider its objective of becoming the leading maritime power is an economic dislocation serious enough to raise questions associated with “how much is enough?” This could cause a major reprioritization of resources away from several maritime endeavors such as the navy, merchant marine, and shipbuilding.

Thus, beyond grasping the magnitude and appreciating the audacity of China’s ambition to turn a country with a historic continental strategic tradition into the world’s leading maritime power, the only practical course for the United States is to ensure that in the eyes of the world it does not lose the military competition over access to East Asia because without assured access the central tenets of America’s traditional East Asian security strategy cannot be credibly executed.

Read the full report here.

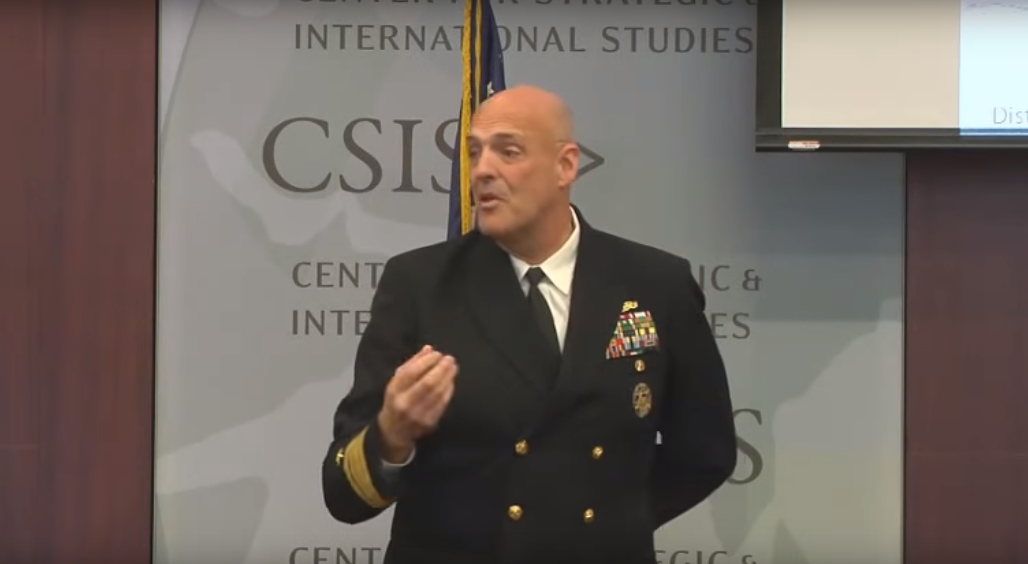

Rear Admiral (ret) Michael McDevitt has been at the Center for Naval Analyses since leaving active duty in 1997. During his Navy career, McDevitt held four at-sea commands, including command of an aircraft carrier battle group. He was a Chief of Naval Operations Strategic Studies Group fellow at the Naval War College and was director of the East Asia Policy Office for the Secretary of Defense during the George H.W. Bush Administration. He also served for two years as the director for Strategy, War Plans and Policy (J-5) for U.S. CINCPAC. McDevitt concluded his 34-year active-duty career as the Commandant of the National War College in Washington, D.C.

1. “Full text of Hu Jintao’s Report at the 18th Party Congress,” Xinhua, 17 November 2012, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/special/18cpcnc/2012-11/17/c_131981259.htm.

2. See State Council Information Office, The Diversified Employment of China’s Armed Forces, Beijing, April 2013. The official English translation is available at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2013-04/16/c_132312681.htm. Also see Liu Cigui, “Striving to Realize the Historical Leap From Being a Great Maritime Country to Being a Great Maritime Power,” Jingji Ribao Online, November 2012.

3. The link to the complete study is https://www.cna.org/CNA_files/PDF/IRM-2016-U-013646.pdf

4. The Diversified Employment of China’s Armed Forces, 2013; China’s Military Strategy; “Xi Jinping Stresses the Need To Show Greater Care About the Ocean, Understand More About the Ocean and Make Strategic Plans for the Use of the Ocean, Push Forward the Building of a Maritime Power and Continuously Make New Achievements at the Eighth Collective Study Session of the CPC Central Committee Political Bureau,” Xinhua, July 31, 2013; Liu Cigui, “Striving to Realize the Historical Leap From Being a Great Maritime Country to Being a Great Maritime Power,” Jingji Ribao Online, November 2012.

5. Andrew S. Erickson and Lyle J. Goldstein, “Studying History to Guide China’s Rise as a Maritime Great Power,” Harvard Asia Quarterly 12, no. 3-4 (Winter 2010): 31-38.

6. See for example, Douglas C. Peifer, “China, the German Analogy, and the New Air-Sea Operational Concept,” Orbis 55, no. 1 (Winter 2001); T.X. Hammes, “Offshore Control: A Proposed Strategy for an Unlikely Conflict,” Strategic Forum 278 (Washington, DC: NDU Press, June 2012); Geoff Dyer, The Contest of the Century: The New Era of Competition with China and How America Can Win (New York: Knopf, 2014), chapter 2; and Sean Mirski, “Stranglehold: Context, Conduct and Consequences of an American Blockade of China,” Journal of Strategic Studies 36, no. 3 (2013).

7. Office of Naval Intelligence, The PLA Navy: New Capabilities and Missions for the 21st Century, Washington, DC, p. 18, http://www.oni.navy.mil/Intelligence-Community/China, and U.S. Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2015, p. 44, http://www.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2015_China_Military_Power_Report.pdf . For comparison, the Japanese coast guard operates 54 cutters displacing more than 1,000 tons. See the Japan Coast Guard pamphlet available here: http://www.kaiho.mlit.go.jp/e/pamphlet.pdf. The USCG currently operates 38 cutters displacing more than 1,000 tons. See the USCG website: http://www.uscg.mil/datasheet/.

8. “Transform Development Mode, Become a Strong Distant-water Fishing Nation,” China Fishery Daily, 6 April 2015. Online version is available at http://szb.farmer.com.cn/yyb/images/2015-04/06/01/406yy11_Print.pdf.

9. China has 6 of world’s top 10 ports in terms of total metric tons of cargo (Shanghai, Guangzhou, Qingdao, Tianjin, Ningbo, and Dalian) and of 7 of the world’s top 10 ports in terms of container trade, or TEUs (Shanghai, Shenzen, Hong Kong, Ningbo, Qingdao, Guangzhou, and Tianjin). No other country has more than one. China also has 6 of 10 of the world’s most efficient ports (Tianjin, Qingdao, Ningbo, Yantian, Xiamen, and Nansha). UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Review of Maritime Transport 2015, http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/rmt2015_en.pdf.

[10] Deadweight tonnage (DWT) is a measure of how much weight a ship is carrying or can safely carry. It is the sum of the weights of cargo, fuel, fresh water, ballast water, provisions, passengers, and crew.

11. The goal of “control” is found in the 2004 PRC defense white paper, from the Information Office of the State Council of the PRC, December 2004, Beijing, http://english.people.com.cn/whitepaper/defense2004. Western naval strategists/theorists normally define “sea or air control” as being able to use the sea or air at will for as long as one pleases, to accomplish any assigned military objective, while at the same time denying use to the enemy.

12. Sam LaGrone, “Pentagon Drops Air Sea Battle Name, Concept Lives On,” USNI News, January 20, 2015, https://news.usni.org/2015/01/20/pentagon-drops-air-sea-battle-name-concept-lives.

Featured Image: Soldiers of China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy patrol at Woody Island, in the Paracel Archipelago, which is known in China as the Xisha Islands, Jan. 29, 2016. (Reuters)