By Andrew Poulin

Andrew Poulin: Good afternoon, my name is Andrew Poulin, President of the Center for International Maritime Security. I am privileged to be here today with former Secretary of Defense Ash Carter here at Harvard University. Mr. Secretary, if you would in traditional CIMSEC fashion, please briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

Secretary Ash Carter: Thank you, Andrew. I’m Ash Carter, Director of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard and an Innovation Fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and former Secretary of Defense.

Andrew: Thank you Mr. Secretary, it’s an honor to sit down with you today at the Belfer Center. The first question we have for you is that, today many senior defense leaders and scholars have described the current international security environment as the most complicated since WWII. How do you see the security environment, and are there latent threats that haven’t received enough attention?

Secretary Carter: The threats that are immediately apparent and that the Secretary of Defense needs to pay attention to today – I always describe it as “the Big 5” – Russia, China, North Korea, Iran, and terrorism. All different. Some actual enemies, some only potential enemies. But, these are all the things we need to have operations plans at the ready for protecting ourselves and deterring today. When you’re the Secretary of Defense, you’re also the Secretary of Defense of tomorrow. And that means, making sure that the two principal things that make the U.S. military the finest fighting force the world has ever known – namely our people and our technology – will be as good tomorrow as they are today.

That’s why Force of the Future was so important to me as a personnel management tool, and why working with the tech sector and acquisition reform was so important to me. And responsiveness, like the MRAP in Afghanistan, was so important, because you don’t know what is going to happen tomorrow and somebody’s going to be your successor. You will need to have left for them as fine an institution as you inherited from your predecessors. So, you are the Secretary of Defense of today and tomorrow.

Andrew: Great, if I could follow up on that, Mr. Secretary, on the five threats you mentioned, certainly they are all getting a lot of attention nowadays. Is there something that you think is not getting enough attention today that could impact the security environment – whether it’s climate change, a biological threat, or something else?

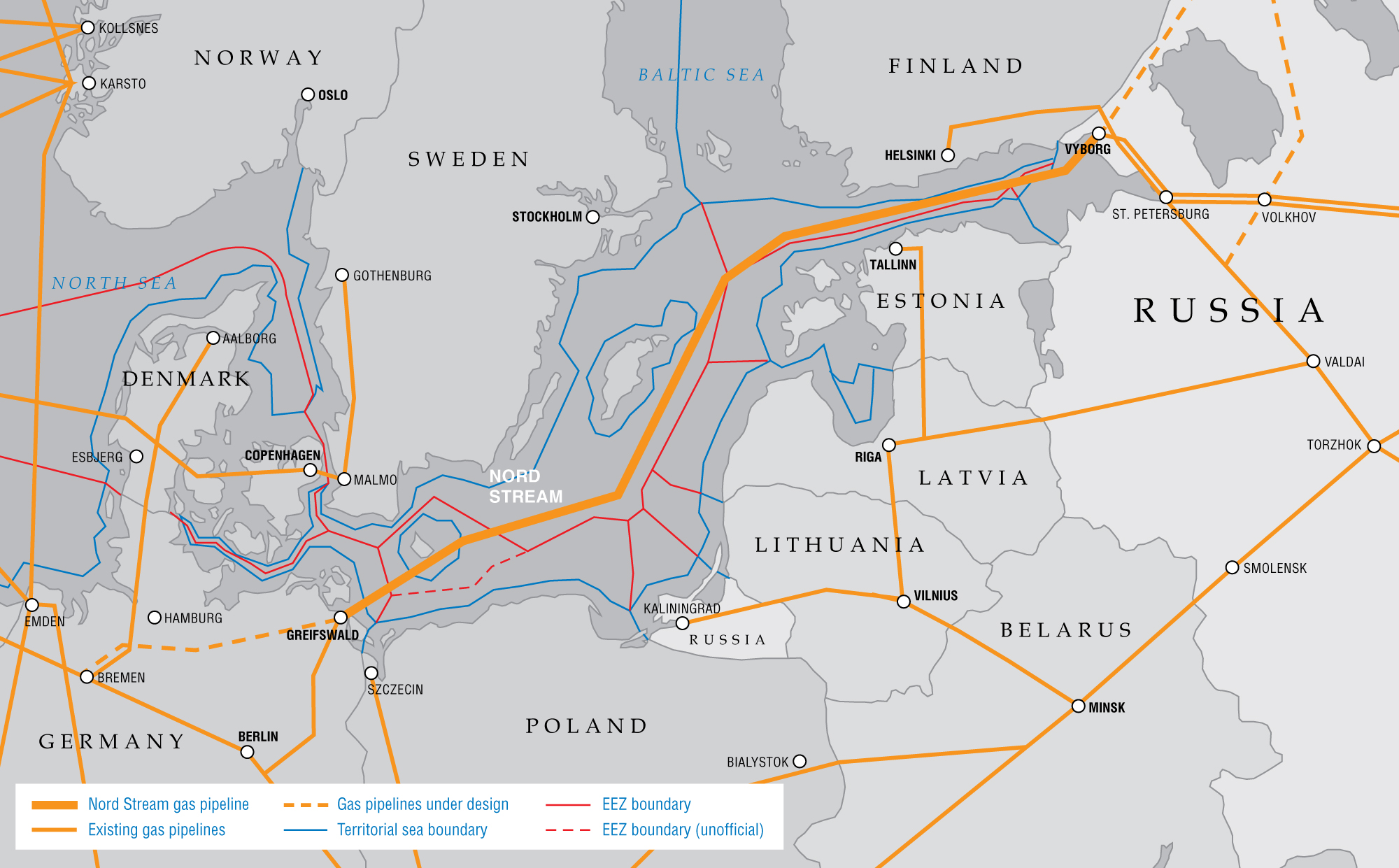

Secretary Carter: There are other things that are not matters of imminent threat that require immediate war plans or action which you keep an eye on for the future. Arctic security is an example of that, it’s not an emergency, but it’s not something we’re ignoring either. It just doesn’t make it to the list of the top five in terms of imminent threat.

Andrew: You were right at the epicenter of the Obama Administration’s rebalance to the Asia-Pacific – since you have left office, there have been a few developments, such as withdrawal from TPP, North Korea nuclear tests, to name a few. What are your thoughts on the evolving relationship between the U.S. and the region?

Secretary Carter: Well, this is the single part of the world of greatest consequence for Americans of the future, and the rebalance was a way of recognizing that. The Middle East is tumultuous but fundamentally isn’t as important to our future because half of the world’s people, half of the world’s economic activity, is in the Asia-Pacific. And there are two big issues there – one is China and one is North Korea. Now North Korea has always been a kind of separate issue – everybody in the region treats it as geopolitically separate from the big issues of China, United States, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia. Those are the big moving parts. So, let me set aside North Korea for a moment.

The rebalance was really about the change in power dynamics, which the Chinese like to say is about their rise, but they’re not the only rising Asian military power. Japan is rising from its post-WWII mentality of defeat and pacifism. India is emerging as a military power. Vietnam has no love lost with respect to China. And in general, this is a region that has no NATO, where the wounds of the past are not healed, and there is no automatic way that peace is kept. And the United States has been one of the principal factors that has kept that stability. That stability will continue to be something we need to work on. China in particular, needs to be pushed back on where it is overweening. So that’s the principal strategic dynamic behind the rebalance.

Separately with respect to China, which gets to TPP, it is the economic arena, which is not entirely separate from the strategic arena, which is why I would say as Secretary of Defense that TPP is a strategic issue. It is for the following reason: China is a communist country and a one-party state, we all need to be realistic about that. Insofar as trade is concerned, that means China can behave in ways that we do not behave – anti-competitive, intellectual property theft, exclusion of American companies, and repression of the Internet. Unilateral decision-making is an advantage that allows China to coercively pick off one company or one country at a time, it’s the reason that they’ll win a game that simply becomes one of no rules and bilateral trade deals.

And that is why abandoning rules-based multilateral schemes like TPP is bad for American companies. We are leaving them and all of the people they might trade with, in Southeast Asia and so forth, to the mercy of the Chinese, acting as though China is like a big France. It’s not. It’s a communist country, let’s be realistic.

Andrew: A great deal of your career has been focused on nuclear weapons and reducing the threat of proliferation, how do you think the U.S. should approach the solution to North Korea? There have been widespread discussions that any military solution would not be a solution at all and would have catastrophic consequences. How do you look at the problem and how can the military better support diplomatic efforts?

Secretary Carter: In the real world, there are not diplomatic solutions and military solutions, there are just solutions. It needs to be said, before we get to what I call coercive diplomacy, which is what I hope we would do at this juncture: the other things that we must do, because any form of coercive diplomacy may not work, are deterrence and defense. These need to come first. And that’s where missile defense comes in, and our forces on the peninsula, and what weapons we’re willing to place there and give to South Korea. So, deterrence and defense first and foremost.

Secondly though, we should give diplomacy a try, both because it might work, and because if the worst is to come, we will be better positioned for having tried it. The way that should work, to my way of thinking, is that you say to North Korea, “If you test another missile, here’s what will happen to you. If you don’t, here’s what the Chinese might do for you.” You work that out in advance with the Japanese, the South Koreans, the Chinese and us. And you pose it as their choice before they act. Right now, we tend to go to the UN to punish them, or go to the Chinese to punish them after they do something, which is certainly justified and emotionally satisfying, but it doesn’t get you anywhere. So, we should try to get out in front of their decision cycle with the carrots and sticks, that’s what coercive diplomacy should be – and it’s coercive because there are sticks as well as carrots. That’s what I hope we will do.

Andrew: Innovation has become a buzzword in the Defense Department today. What is your definition of innovation, and how can leaders up and down the chain of command really encourage and foster that environment?

Secretary Carter: Well, that’s a really good question because a lot of people only think about technological innovation, but that’s only one kind of innovation. There’s doctrinal innovation, there’s innovation in how we recruit, train, and retain talent. Just to take that one – out in the world around us, there is a revolution going on in how talent management is done. We can’t use all of those techniques, but we ought to pay attention to them and draw upon them.

Doctrinal is meant by, and we can’t go into detail on this but your readers will know some of this, that I was constantly telling our people who draw up our war plans that they need to look at them again and again and say ‘Is this really the best approach?’ And we had some that were not up-to-date in that regard. I, for example, did not think our China plan was where it needed to be until Sam Locklear and Harry Harris began working on it. Mike Scaparrotti and Vince Brooks did a great job with the plans for the North Korean peninsula, of which there are several.

And then of course is the matter of technological innovation. The key is to keep us connected to the commercial and international tech base, because we have a big tech base of our own, but it’s not enough anymore. It was enough 50 years ago because there was nothing much outside of the Pentagon’s five walls, but now there’s a lot and we’re not going to be the “firstest with the mostest” as Lyndon Johnson would say, unless we’re connected to the big world of tech out there.

Andrew: One issue I’ve heard you speak and write about before is that you seem very passionate about is developing the next generation of leaders. Not many people would come from your background of being a double major in physics and medieval history, and then go on to be Secretary of Defense. Can you briefly walk us through your own life of service and what lessons you took that now informs how you look at developing the next generation of leaders today?

Secretary Carter: As there are in the lives of all people, a certain amount of chance and accident. You don’t plot this out – you don’t start out at twenty-two years old and say “I think I’ll be Secretary of Defense of the United States.” I had no knowledge of or ambition for public life at all. I was asked as a young physicist to work on a technical problem of importance to defense where my knowledge was thought to be able to make a contribution. That was the issue of how to base the MX intercontinental ballistic missile. And it was supposed to be for just one year…36 years later I walked out of the Pentagon last January!

But I was struck by the seriousness of the issue with which I was dealing. It was the height of the Cold War, so nuclear annihilation was at stake. I could make a difference, in this case, because of my technical knowledge, and if that knowledge were not present in the room, a good decision would not have been made. And I thought, “Well, that really is a good feeling.” It mattered that I was there for something that was big. What better feeling in life can you get than that? So, you can go out and sell stuff and that I’m sure that is satisfying, but that’s not the same as saving the world from nuclear annihilation! Or, you can be a cog in the wheel of government and feel like it doesn’t matter that you’re there or not there.

And I had those two things come together for a moment, and that grabbed me. The other thing that was big was that there were people, military and civilian, in the generation above me that reached down and identified me and said, “Hey, keep doing that.” One of them was Jim Schlesinger who was Richard Nixon’s Secretary of Defense and another one was Brent Scowcroft who was George H.W. Bush’s National Security Advisor, and another was Bill Perry, President Clinton’s Secretary of Defense.

Andrew: Good mentors to have!

Secretary Carter: They were wonderful. They were everything that you would want – they were people of tremendous ability, patriotism, and dedication, but also very decent people who cared about tomorrow and not just today. It mattered to them that they developed the people who came after them. And so, they spent a little of their time and their energy paying attention to somebody who was a nobody because maybe I would stick with it. So, you ask, how do I have such a strong interest in our people in the military and DoD generally? It’s because somebody paid attention to me and it made a difference.

Andrew: Following up on that, how would you characterize your leadership philosophy – is it what you just outlined – take care of your people – is it reach forward while also reaching back?

Secretary Carter: I think my leadership philosophy is, have very high standards but also get the best out of people. And that means being strict when their conduct is not up to standard. But also making sure that you’re always getting them to do their best and giving them attention and credit so they are doing their best. The people that work for you are force multipliers. And I had the great fortune of having 2.8 million of them, and I thought I was the luckiest guy in the world, because if I only gave them a chance they would do spectacular things, and they did time and time again. That’s the way to do it. Of course, on the other end, it takes the excellent people that we have there and that’s why I’ll be proud to have been part of the Department of Defense of the United States of America for the rest of my life.

Andrew: One last question, is there anything you are reading currently or books that you read in the past that shaped you or are influential in looking forward?

Secretary Carter: I read the memoirs of people who came before us. And it’s good to remember that we owe something to those who come after us. And it matters that we do the right things. It also matters that we act decently and that we behave ourselves because our children our watching.

Andrew: Great, well thank you so much for your time Mr. Secretary, it was an honor to have you join us today.

Secretary Carter: Good to be with you Andrew. You have a great organization.

The Honorable Ash Carter was the 25th Secretary of Defense and is currently serving as the Director of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard University and an Innovation Fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Andrew Poulin is the President of CIMSEC. The comments and questions here are his own and do not reflect those of the U.S. Navy or Department of Defense.

Featured Image: Secretary of Defense Ash Carter speaks to attendees of a ceremonial swearing in in the Pentagon Auditorium, March 6, 2015. (DoD Photo by Petty Officer 2nd Class Sean Hurt/Released)